I don’t know where Mom learned to drive. I don’t know where she learned to hold the wheel firm or belt my chest with her right arm whenever we stopped suddenly for the stray deer lying in the road, still half-breathing, or the broken homes that spilled their bricks onto the whitened dirt.

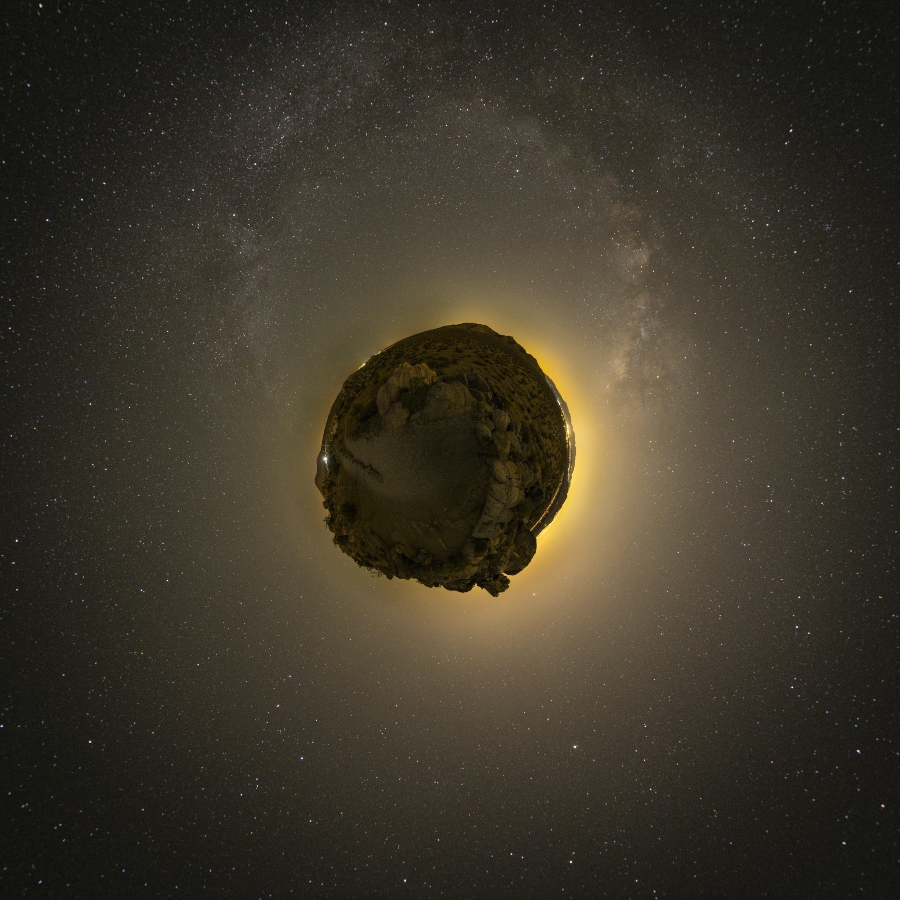

Last night, the man on the radio spoke of some rock, some piece of mountain falling from the sky. He said, Please stay clear. It will bend trees, take apart homes, melt glue and nails, turn crops to craters.

He mentioned the name of a village at the center of impact. Mom said, That village used to be home. When you were still in my belly. Do you remember?

The neighbors gave her the keys to their broken car, and she gave them the cookie tin full of coins and jewelry. They asked, Where will you go? Where will you take your little boy?

We arrived at the village, her once-home. It resembled our other village, the one we’d come from, my once-home. Houses collapsed onto their broken foundations, their walls dotted with white soot. I recognized where the gunpowder had bitten into the wood, poisoned the river with lead. I recognized where the soil had become pitted by the worms, the flies, and the boots of hungry men passing through with uniforms tied around their waists, sweat licking onto their upper lips.

With the homes vacated, the last villagers trailed down the road, shaking under the strain of books, photographs, and clay pots strapped to their shoulders. Mom watched them from the car, thought of her parents’ words from so long ago. Where will you go? Who will take you in?

She took a bag full of tools from the back of the car, held my hand as we found our way to one of the few homes with its head still lifted. I looked up at the sky thinking I’d see the shadow of that falling piece of mountain.

The door was unlocked, and the home was empty save for papers, the smell of moldy jujubes, a wooden crib tipped to its side.

She laid out the tools, and I drilled holes in the floorboards the way Mom told me: deep enough that I could feel dirt sticking to the auger, the wood coming loose like paper skin.

With the boards gone, she gave me the trowel while she held her shovel, the handle already smoothed by the months she spent clearing our fields, hoping to de-seed the fungus.

We’re digging a place of rest for that stone in the sky, she said, Dig until the ground is as tall as me and then a little more.

She raised her arm above her head, and I jumped to slap her hand. She caught me, kissed where my shoulder folded to my neck. She laughed and I laughed, and I didn’t think there could be anything brighter than the way that she smiled, held each breath between her teeth, looked at me like she knew every good thing that I could ever become.

She spoke of the stone as a seed, and I imagined grapes, plums, melons, new roots with soft voices full of juice and pulp.

Hours passed, and we stood in a waist-deep hole. The man on the radio said, You can see it now in the sky, between the stars. Impact in eight hours.

But out our window: clouds, a diffused light, a faint moon cupping the sound of cicadas.

This will have to do, Mom said, and we lay in the dirt. She held me close, the smell of lemon and perilla in her sweat. She whispered the bedtime story about the man with our surname.

They called him a war hero, she said, He sank with the ship, guided people to rafts even as he swallowed saltwater.

But he made a promise, she said.

But there is only so much to take, she said.

I fell into a dream where I heard her say, I’m sorry, maybe it’s not too late.

Morning: Mom sat in the doorway. The men on the radio spoke over themselves about trajectories. They explained that even math could fail to predict the turning winds, the way that air can prevail.

The stone skipped into the ocean, they said, No casualties.

I wiped the strange tears at her cheeks, careful not to get dirt in her eyes. She pulled me into her lap, and I asked her about the seed, the stone, the mountain. She wiped the hair out of my face and pressed her lips into my face over and over until I could taste salt through my laughs. She smiled, like a dimming sun.

I wanted to ask her why she was crying. I wanted to ask her what she wasn’t saying to me, but she turned my head and pointed over the hills standing guard outside the village.

I could have sworn, she said, I could have sworn I saw the sea there.