by Betty Martin | Aug 26, 2024 | flash fiction

The giant orb in the night sky makes our friend’s house look like a doll’s house. One of us mentions this and another of us scoffs, “As if.” We clutch sleeping bags in our arms, plain ones without characters. We borrow them from older siblings, or our parents buy them when they give in to our pleas. Some of us miss our Powerpuff Girls-, Sailor Moon-, or Polly Pocket-themed sleeping bags. None of us admit it. We troop inside and mutter hellos to our friend’s parents, who answer us with great big hellos and usher us upstairs. Our friend has turned thirteen, and we are here to celebrate at her birthday party sleepover.

Everything’s set up in our friend’s bedroom. Candy, chips, more candy, more chips, and liter bottles of caffeinated soda; all are our appetite’s desires. We dump our sleeping bags in corners. A breeze from the window tousles scraps of paper in a glass ashtray set on the floor. The scraps of paper have our noms de sorcières written on them, passed to our friends during the day at school. An orange BIC lighter our friend swiped from her parents rests nearby. We form a circle and sit cross-legged, joining hands. We evoke Hecate, Circe and Vanilla Mieux, Medea, Sabrina, and Hermione Granger. We call to Angela Leon. We call to Morgan le Fay. We ask for their blessing and then we chant our chosen names. Our friend swipes a thumb over the metal wheel on the orange BIC lighter, igniting a holy flame, setting the scraps of paper on fire. We’ve all seen The Craft.

“You better not be smoking!” shouts a parental voice from below. Our laughter floats out the window and down to the patio where our friend’s parents sit smoking Newports. We watch the fire consume our names until there’s nothing more to burn.

Anticlimax. Ennui. Each of us feels the letdown. No transformation presents itself. Our host saves us. “Let’s do our faces!” We take out our makeup, leftover lipsticks moms have given us, Hello Kitty eyeshadow kits, and real eyeshadow kits, stolen from our older sisters. Lipstick goes on lips, eyeshadow goes on eyelids, and blusher goes on cheeks. We go creative after that, beauty marks dot green cheeks, red lipstick smears on eyelids, and eyeliner inks eyebrows as thick as caterpillars, as black as soot sprites.

We test our magical powers. One of us volunteers and lies down in the middle of the room. We each place a finger underneath and chant, “Light as a feather, stiff as a board.” Our friend swears she lifts off the floor. Our power proves itself. “Now, do me!” insists another.

We grab the Ouija spirit board, daring each other to ask. “Does he like me?” Some of us replace the spoken pronoun “he” with a silent “she.” “Yes,” “No,” “Good Bye,” we hold our tender hearts in our hands until we get the answer.

“Music Time!” shrieks the birthday girl, pressing the power button on a birthday-present boom box. Two round speakers protrude from a yellow CD player. Yellow CD player eyes fill the room with sound, and we dance, careless of its gaze. Arms stretch, hands reach, torsos twist, hips gyrate. We follow the beat, the rhythm guides us. One of us grabs an empty Pringles can, an instant microphone, and lip-syncs to a sultry song. “Crank it up!” so loud we barely hear our friend’s parents say, “This is positively The Last Sleepover.” It makes us laugh all the harder.

Mardi Gras necklaces jangle against our chests as we jump and writhe. One of us leaps onto the bed and quirks a Britney hip thrust. Our friend’s little toy poodle yaps and runs in counterclockwise circles. Black barrettes on curly white poodle fur hop and skip and come loose. Our laughter explodes. One of us spills soda on the carpet. The little toy poodle laps it up and all of us shriek.

“I’m going up there.”

“Let them have the night.”

Our night. Seven best friends who are, finally, all of us, thirteen.

One last game before it’s lights out, a new game we’ve all just heard about, not yet named, described in whispered conversations in school hallways and the girl’s changing room. “Shh!” says our host, and we obey, exchanging half smiles, suppressing half giggles. Our host empties the snack bowl, and we tumble in our treasures, booty from medicine chests, bedside tables, and pocketbooks. Our friend rotates a spoon around the bowl; ovals, oblongs, and circles, white, pink, and peach, rattle together. A blindfold goes around our friend’s eyes—the birthday girl goes first and closes a hand over a pill. The blindfold passes from hand to hand, and we all do the same. With a show of hands, pop go the treasures into waiting mouths. A soda swig and a swallow, and now we wait.

Not for long. We dance the dance of goddesses, of sorceresses, of mages. Pores sweat, hearts pound, heads buzz, eyes divine. We’re walking on sunshine. We’ve got the power. We have the touch, the music is in us. We commune with the cosmos and feel every particle. One of us floats to the ground. One of us falls off the bed. We lie on the floor and watch the ceiling sparkle with colors, race with contrails. One of us will haunt these kinds of parties, Skittles parties, a sweet candy name, a fun name. One of us wants to have more fun, to fly above the fog of despair thickening each day. One of us will plummet into addiction. But on this birthday night, all of us fly together over a hunter’s moon, all of us dreaming, none of us knowing.

by Mimi Manyin | Aug 22, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

My son…he’s a good boy. I hug him as often as I can. Casey is almost five now, but he’s small for his age, so he feels more like a three-year-old. I want to hug him like this forever. I want him to hug me back like this forever – with both arms and legs and all of his little body. He won’t hug me like this when he’s older. I know it. He will want to hug someone else – someone prettier, someone younger, someone his age. And then I won’t have anyone to hug.

I moved to the suburbs three towns over from our old house. I want to be far away from Joe, so I won’t run into his friends and relatives. I don’t want anyone to ask about our situation. All I can rely on now is the Voila! app on my phone. Everyone loves this app. I use it to make duplicates of my favorite donut. I snap a picture with the app, press send, and voilà, a copy pops out of the Duplicator I have at home. Making duplicates feels good. I can make as many copies as I like until my stomach feels satisfied. One more chocolate-glazed donut and one more glass of wine before I go to bed. Joe is not here to remind me I’m not supposed to have any more or tell me I need to lose weight. One is fine. The duplicates don’t contain the sugar or the alcohol, so it’s no big deal. Slightly less palatable, but the satisfaction is real. They fill me up every time.

The bakery down the street doesn’t mind people snapping pictures of their pastries inside the store as long as you buy a dozen to go. They know the experience cannot be duplicated entirely. These are just copies. They look the same but don’t taste the same. Not quite.

Casey and I used to choose together which donuts we wanted to duplicate. I always had a clean plate right by my Duplicator. I would snap a picture of the donuts and out popped the extra ones onto the plate. We had such a great time. Once in a while, I also made copies of Casey’s stuffed animals so he could have more friends. Casey craved hugs like me. He told me his arms would ache if he didn’t have anything to hug. Seeing him surrounded by friends made me feel loved, too. It made me feel like a good mother, especially when I was at work and I couldn’t wrap my arms around my boy to comfort him.

I did it at my last supervised visit. Casey had fallen asleep on the couch while watching TV. Joe told me they needed to head out soon. Casey had a play date at four so it was better for me to leave now before he woke up. Joe said all this with his back toward me as he climbed the stairs to get Casey’s stuffed elephant for the car ride. He didn’t even look me in the eye. Seven years of marriage! As soon as he was out of sight, I snapped a picture of Casey. God knows when Joe would suddenly stop letting me come over for visits, supervised or not.

The duplication took much longer than I expected, but it worked. After putting it together limb by limb, my copy looks just like our Casey. He doesn’t say or do much, but he is with me and he is happy. When we go for walks, I dress him up warmly and let him ride in the stroller. We go shopping and we go to the park. When we get home, I let him fall asleep on my tummy, and I hug him nice and tight through the night. He doesn’t mind if my tears spill onto his pajamas. He knows how much I love him.

I wish I could make a copy of Joe, too, but he never falls asleep on the couch. He keeps his eagle eye on me at all times. He locks his fridge and his wine cabinet. He always positions himself between Casey and me as if I’m going to do something bad. I’m not a monster. He doesn’t have to treat me like this. Mothers would never harm their children. Joe should know that. He said I was scaring Casey. I wasn’t. I just wanted to hug him. Who is going to love me now? Joe told me I needed to pull myself together. He said he still cared about me, but he couldn’t be with me anymore. I told him that was bullshit. If he loved me, he would have helped me instead of kicked me out. I yelled at him to prove his love and he turned his face away to wipe his crocodile tears. He said he wished he could have the “old me” back.

I know he has a copy of me somewhere in his house because he used to love me. I don’t want him to love a copy of me. I want him to love me and keep me.

Tomorrow, I’m going to sneak inside his house and get rid of that copy. Then I’ll stay. I’ll make myself huggable without all the unhealthy ingredients, so both Casey and Joe will love me again.

Just hug me one more time. Just one more.

by Diane Gottlieb | Aug 20, 2024 | interview

I’ve been a fan of Constance Malloy’s for quite some time now. I always look forward to her posts on The Burning Hearth, and her memoir Tornado Dreams speaks to trauma and the path to healing with great courage and hope. Her latest book Born of Water: A Hybrid Novelette (ELJ Editions) is a beautiful example of Malloy’s vision and versatility. It was my great pleasure to speak to her about visions, writing hybrid, and the freedoms that both provide.

Diane Gottlieb: Congratulations, Constance, on your gorgeous Born of Water: A Hybrid Novelette! I love hybrids—and this one is a masterclass in hybrid writing. I read your memoir Tornado Dreams, and while some of the events in Born of Water are lifted from the real-life experience, they are woven together with speculative, futuristic, and fictional threads.

You even get a little meta at the end of Part One:

“Believing a character’s relationship with the author is an intimate dance predicated on the need for independence, which is necessitated by the need for dependence and borrowed experience, I promise Mari to listen to her story without interfering, and to open myself freely, so that she may take from me whatever is required for its telling.

It feels like you added nonfiction elements in the service of telling Mari’s story—which is fascinating. Can you tell us how you came to that decision, about your process?

Constance Malloy: Including nonfictional elements from my life into Mari’s story was not so much a decision as much as it was an organic pulling from my experience to tell her story. Something, I believe, all writers do. As I say in the quote above, it comes from her “…need for dependence and borrowed experience….” Because of my personal history, I’m compelled to tell stories about self-abandonment, what happens when that self-abandonment continues over years, and what is required to reclaim the self. So, Mari borrows from my experience. As a character (more specifically as a character of my creation), she depends upon me to free up that experience for her and grant her the autonomy to use that experience as she sees fit.

Including the meta section in Part I was a decision I made. So often authors are asked where their characters come from. Reflecting on being asked that about Mari, I felt it was important to tell the story of her origin. I want to believe that adds depth to her story, while also giving readers something to chew on about the author/character relationship.

DG: What freedom does writing hybrid give you that writing either straight-up nonfiction or fiction can’t provide?

CM: So, way back in the mid-1980s, sitting in Jane Smiley’s creative writing classes at Iowa State, I was already beginning to do hybrid writing. I loved mashing up elements of fiction and nonfiction. I loved throwing in a poetic line here and there. I loved adding the surreal, the ethereal, and the speculative to the real. Jane suggested that I decide what kind of writer I wanted to be. But honestly, I didn’t know how to do that because my brain simply works in all of these modes. And most importantly, stories come to me in all these modes. I’m a purest when it comes to rendering stories the way they present themselves. It’s very seldom that a story comes to me as one genre. Although, I do have a fantasy trilogy in the hopper (has been for 30 years) that is 100% speculative fiction. In short, writing this way gives me the freedom to be who I am as a writer.

DG: Many of the chapters have dreamlike elements. You and I have spoken before about dreams being real. Can you share your thoughts about that? Are visions real? What is real?

CM: To me, visions are absolutely real. In fact, they are an integral part of my life. Dreams and visions have helped me; they’ve prepared me, as my dreams did in my memoir Torndado Dreams, to climb the cliff in Born of Water; and they keep me in touch with the realms that exist beyond this human, Earth-bound, experience.

DG: Nature and the natural world are prominent in this book. Mari has earned great acclaim for her work of writing obituaries for bodies of water, which according to the character Rhys Jensen, the former Lake Michigan representative for The Great Lakes Consortium, have “changed the lens upon which we absorb the myriad of uncomfortable truths we now face because of our shared failure to protect the only home we have.” What a powerful statement!

How important is it to you to speak to the real problems of our world, such as climate change, in a fictional, futuristic way?

Constance: Having been influenced by Star Trek since the age of 5, I believe it is now in my blood to talk about uncomfortable realities of the present from a place of distance. But life is like that, right? I didn’t write my memoir while in the middle of my therapy. I didn’t write climbing the cliff while I was on it. We need distance and perspective and time to understand and recognize outcomes and consequences. But I believe there are some of us who can look at systems, recognize how they are functioning, extrapolate future behaviors of people based upon their current actions, and roll all that out to a logical conclusion. A bit off topic, but my mother has often told me of her expectations she had for her future with my father, which were miles away from her reality with him. My constant refrain has been, “What about your past experience with him made you think that was possible?”

Placing things like climate change in the future allows for A plus B equaled C. The writer can show how certain actions or inactions lead to particular outcomes. You can remove the speculation through the speculative.

DG: You’ve written memoir and now hybrid. What’s next for you?

CM: I want to continue the story of Mari and Rhys from Born of Water. I have a few essays I want to pen. I’m beginning my co-author journey with Kris Roberts. (For those who’ve been following the story, she is the woman who was abducted leaving my house when we were children.) And then, there’s that trilogy that’s been in the hopper for 30 years.

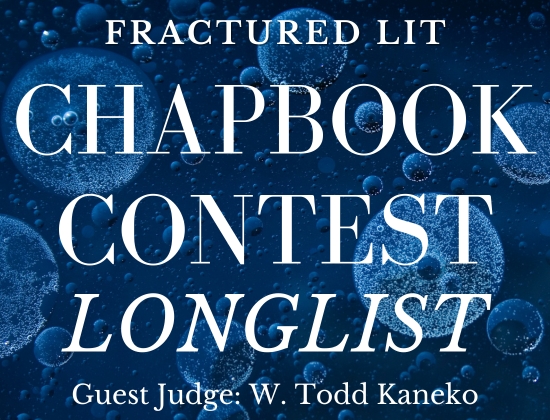

by Fractured Lit | Aug 20, 2024 | news

This has definitely been one of our hardest contests to decide on a longlist. We had the privilege of reading many fantastic chapbooks over the last few months, and we’re sad we can only pick one winner. Here are the titles of the thirty-five that make up our longlist.

- Fish Eyes

- My Years of Blue Violence

- The Start-Over Game

- Nectar & other stories

- Picking Up Stones

- Playing Pretend

- Various Dispositions

- Everything Bites

- Consider the Grease Traps

- Little Knives

- Hurt Me

- False Life

- Nicotine Walls

- Lisa Longs To Hold Harry

- Every Twelfth Tree

- Fighting my enemies in the Applebee’s parking lot

- Roll and Curl

- Dementia and the Wild Man

- Family Haunts

- Like Oil and Water

- Mulch

- The Afternoon of Family

- All the Small Things

- Butterscotch Yellow, short fictions

- Shoreline

- Meanwhile, In the Hungry Dark

- Have Headphones — Will Travel

- You Go Home

- Dreamboat

- Kaleidoscope

- Secrets and Truths

- Jazz Picnic: Very Short Stories

- The Rest of My Life Might Be Razor Wire

- I Spent the Summer in Chengdu

- On the Batang Ai and Other Flash and Microfiction

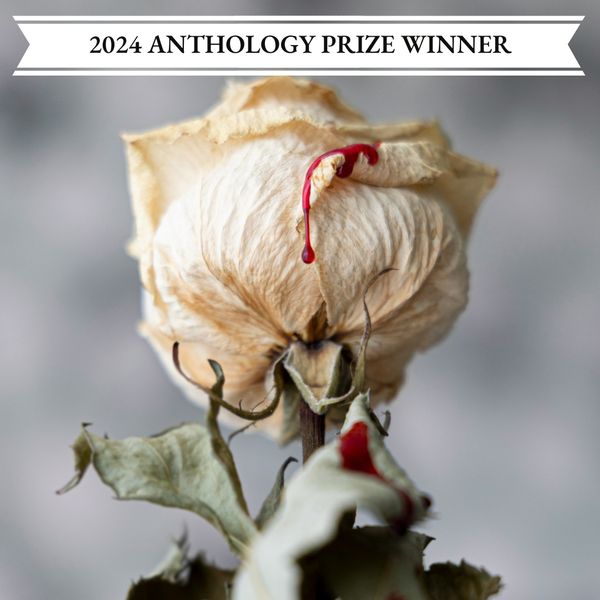

by Elia Karra | Aug 19, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

When the first of the last coughs come, I take my father to the sea. I know he likes it there. Every time memory resurfaces and reveals his previous life—before my mother, before me, long before the sting of IV lines and the smell of disinfectant—he talks about all the places he’s been. The Panama Canal, the Suez Canal, the Isthmus of Corinth. Tiny, cramped spaces that are neither here nor there. All these in-betweens.

Make sure to put a coin in my mouth.

Does Charon take euros these days?

He can still walk and we walk together over sand and pebbles and green glass shards. A year ago, we were in The Hague, salt-whipped and chilled to the bone by the North Sea. Our Aegean is calmer, even this time of the year, but he’s bundled up in the same coat because he can’t handle the cold anymore. The shore is quiet, empty. The seagulls have come back to take their rightful place.

We used to come here when I was a kid. Every summer spent swimming and building sandcastles. My father, in the same bathing suit since his Navy days, coffee and cigarette in hand.

Did I tell you about the time we jumped in the Atlantic?

Yeah. Tell me again.

He tells me a gasping, wheezing story. He remembers some things wrong or maybe this is the first time he remembers them right. It was so cold, he tells me, they had to huddle up for hours afterward. In past retellings, he was back on duty in the engine room, sweating as the others shivered.

He shivers now, either with cold or with the echo of that day. I haven’t hugged him since I was twelve and so I don’t. He puts his red, steroid-swollen hands in his pockets instead and gazes at the waves, the lace of foam draped over the rocks. The skin on his face is taut, stretched thin over his skull. Smooth as the stones beneath our feet. I can’t remember him any other way. When I think about childhood recitals, birthdays, those days at the beach, he looks like this: old but not old enough, too-thin torso, too-big limbs. His past selves overwritten.

I brought him here for a reason. I brought him here because his lungs are failing him and the air hurts, so maybe he doesn’t need his lungs and he doesn’t need the air. I take off my shoes, my socks, my jacket, lay them on the sand. My father watches, shakes his head. He always needs some coaxing.

Come. It’s only water.

She cradled him once, this wine-dark sea, and she’s called for him ever since. The crash of the waves, the crunch of sand. Her ghost in the conch shell he brought with him from the Caribbean coasts. He can answer her now. There’s nowhere else he has to be.

We stand ankle-deep in the water and it stings like a hundred little jellyfish. It soaks the cuffs of my jeans. The cotton sticks to my legs like a second skin. Beside me, my father begins the long, laborious trek out to the deep and I follow him, hands flying out to steady him when he falters.

And then the sea holds us, and we’re weightless despite our soaked clothes, treading water as if we were always meant to. A homecoming.

But we’re not built for this, not really, and transformations are slow processes. Flesh torn and reshaped, forged into something new. The sun path is short these days and by the time the first gill appears, reddened and tender on the expanse of my father’s ribs, the seawater shimmers with the last of the light. He coughs, the bone-rattling cough of a dying man. He spits salt and saliva, beats the discomfort out of his chest with a fist.

Does it hurt?

No. I just have to find my sea legs.

I wait until he does. I wait until three gills form on each side of his torso, until his lungs finally rest. Until he draws water into his mouth and doesn’t choke, until the last of the coughs is silenced.

Grief is to the body as silt is to water.

My stomach is full of brine when I drag myself to shore, my clothes drenched and heavy. It’s dark now and I have to feel my way to my jacket, fingertips over pebbles and grit and sea glass. I gather my things and his. He’s left behind a coat, a pair of shoes. A few people.

The waves crash in, reaching inland, lapping at my feet. I like to think I can still see him, in the distance, though it’s dark and he’s too far into the sea. In his coat pocket, I find a coin, small and shiny, round like the moon that pulls the tides. Payment for a safe passage.

by Lori Isbell | Aug 15, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

We were sitting in the stadium waiting for the Face. It came at 6:45, right-center field, or that’s what I’d heard because I hadn’t seen it yet.

I was there with my son and one of his friends from the city league—Kierran or Kellan, scrawny kid from the west side. Whose parents were both lawyers and bought him a three-hundred-dollar glove, which he mostly sat on so he wouldn’t get dirty. Which my wife says is none of my business, but there you go.

She was at home, my wife. Said the Face was a marketing gimmick. Some digital whatever—a hologram, I think. Some way to get people to the ballpark early so they could buy more beer and nachos, nine-dollar dogs. Not even a Face, said my wife, probably a logo or something, and she wasn’t driving all the way downtown in traffic when she had things to do—laundry!—by which she meant Netflix.

So, I’d brought the boys. The hot dogs weren’t bad. And if seeing a game could help my son learn to lean into the plate and stop whaling at the ball like trying to bring down a plane, well, I figured, it would be worth the trip.

Because you had to make a trip if you wanted to see the Face. It didn’t show up in the pictures or the videos people took, so you couldn’t see it online—couldn’t get it on your phone. Which pissed people off, even if it was Jesus.

That’s what people were saying: the Face was the Face of Jesus. Though some said it was the Dominican reliever the team had signed, or the winner of some contest, a reality show. My buddy at work said it was the guy with the weird hair from the China thing.

I turned to my son and his friend. “Guys, you ready?”

“I’m on a level,” said my son, thumbing at a tiny screen.

“For the Face,” I said.

“Dad, not now.”

“There he is!” said Kerwin, or Klennan, my son’s friend.

But he meant the mascot—the guy in the furry suit—and the boys went back to their phones, their games. I checked my own phone: 6:43.

A nun shoved past me. The religious types were here, with the singing and praying and end of something. Or beginning. Not that I’ve got a problem with the religious types, of course. But if you want to hail a Mary, or amaze a little grace?—don’t go putting your elbow in a man’s Coors Lite.

More people mashed in, along the steps and in the aisles. Pushing into rows, trying to get a view. Most of us were on our feet and straining to right-center, when it seemed like in the distance…maybe, I thought I saw…but then the crowd heaved over and we all went down.

So I can’t really say if I saw the Face or I didn’t. When the bodies went horizontal—people shouting and crashing hard, on the seats, on the floor—I pulled my son and his friend close, covered their bodies with mine.

My wife wanted to know why we were home so early. I had to explain about the night and how our son cracked his screen and why we smelled like beer and mustard from the deck of Section J.

She put our son to bed.

I checked my phone for the Face.

by Jim Humes | Aug 11, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

Look at their body language: Henry grips the wheel with his left hand while the other chops at the air. Marilyn stares out the window. They are driving down a two-lane road charred silver by the summer moon.

Without saying their goodbyes, they’ve left a house that heaves with life. Peek inside and you’ll notice sparkling teeth, crinkled faces, and hands fluttering cartoonishly. A drunk girl stirs a clutch of spaghetti into boiling water. Sodden jocks hold a séance around the sports highlights. In the backyard, clusters of teens mirror the patterns of stars above them. A boy throws up next to his car. A girl hides beside a whirring air conditioner to weep. And here—someone sits on the roof watching his cigarette smoke curl up toward the vestments of night. The scene resembles a coral reef, doesn’t it? Or a just-shaken snow globe. You might ask, where are the parents? Who watches over the children?

Back to the car, their conversation, Henry’s plea. He wants Marilyn to remain his true love when he leaves for college. He tells her this is the right thing, the only thing to do. Listen to the song spiriting from the tape deck—a divination of satellites and love. For her every objection, he offers the same reply: we orbit each other.

As they approach the hill that climbs out of the canyon, Henry stands on the gas. His sporty green coupe whines with all its might. On his yellow tee shirt, you might recognize The Great Wave off Kanagawa printed across the chest, the rowers digging into the face of that enormous, clawing wave, propelled forward by the inexorable coil of life inside them. Henry wants to fly over the crest and relieve Marilyn of the gravity that weighs her down.

She doesn’t enjoy this game. As Henry’s body leans forward for more speed, her fingers whiten around the grab bar next to her head. She turns her eyes forward, dark and defiant, bracing herself for weightlessness.

Now, let your attention wander up the road. A white car coming toward them bends around a curve. A woman whose face is filled with woe drinks from a Styrofoam cup. Her headlights paint the oak trees ghostly white, revealing the twine of their witches’ arms. Jeweled eyes flash in the darkness—a possum, a gaze of raccoons, the green glow of a coyote sauntering along the asphalt. As the white car approaches, the woe on the woman’s face disappears behind the full moon of her cup.

People in accidents say they ignored the signs. The angle of the headlights drifting toward them. The mesmerizing constellation of bugs across their windshield. The slow fade of the satellite song coming to an end. Henry remembers picturing a matador dancing right and then left. He replays the details for decades:

Two tires slide off the road.

His foot remains locked down on the accelerator.

The car jerks down the embankment like a hooked fish.

A tree bends out of the way.

He steers the wheel hard right.

He reaches for Marilyn.

A mortar explodes, and everything turns upside down.

Elephant.

Feather.

Elephant.

Feather.

Coins and cassettes and papers fly like confetti.

Birds, nesting for the night, scatter.

When they come to rest, the dangling side mirror reflects a sliver of moon. The metal wadded around them ticks and tocks. Henry reaches for Marilyn, but his arm won’t lift. She is curled up against her door, shutting him out yet again. Tiny roses bloom in his vision, and he begins to understand. It’s been a long day. He closes his eyes, if only for a moment.

Here’s a detail that’s easy to miss. A few miles up the road, in a house with one glowing window, Marilyn’s father, an oncologist, confronts the image of a tumor. A glass of ice water sits at his elbow. He is unaware that tomorrow, he will stand before a group of young people gathered in the ICU’s waiting room and tell them that the damage to the brain stem was beyond repair (“the” brain stem, not “her,” he realizes on that first anniversary as a thin keening sound splinters from his chest). The children will sit stunned by this impossibility until a girl (the one crying at the party) emits a squeak, triggering a wave of sobbing, shaking, and clutching that passes through them all. But tonight, he attributes his uneasiness to the careless ring his water glass reveals when he lifts it.

Now, back to Henry, strapped in a car that hisses its disappointment. He wears bits of glass like a crown. Blood blossoms scarlet across The Great Wave. Notice the flap of skin on his forehead that will leave a scar shaped like a smile. Watch his chest heave as an elephant’s foot steps down and a bird flaps up against its cage. Marilyn fell in love with the long black eyelashes that flutter in his dream, the broad shoulders and impossibly strong legs curled up beneath him. She fell in love with the books that mark the trail of their tumble, the metallic tapes filled with stubbornly eclectic music that flutter in the branches.

Our job is not to project, but should you picture these two as your friends, your children, as people you once knew, you can glide into this world. Here’s what I see: Henry’s body heals. He dives into his studies with blinders focused only on the future. He finds another love, fair and forgiving, and they create a family complete with a son and a daughter and years of meandering happiness. But on certain nights, when the world blazes like a pearl, he feels a shadow towering over him. He takes a deep breath, ready to surrender to its weight. Then his wife’s simple question, “What’s on your mind?” wakens the coil of life inside him, commanding him to paddle harder, paddle faster, and fly over the history that would otherwise swallow him whole.

by Wendy Holmes | Aug 8, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

I was in her backyard, the tiny fenced-in yard behind an extravagant Brooklyn brownstone. I had the baby, Violet, in my arms, and my son, Jasper, was running around with Mateo—both goofy and uncontainable. They were doing the work of four-year-olds—transmuting the world into play. My neighbor, a petite and fragile woman, stood silent, hands on her hips, eyes glazed over. It was spring, and the maple in her backyard stretched high above the brownstone. The tree had been there a long time, longer than the house, perhaps longer than the neighborhood. The tree could not contain itself; little seed helicopters were spinning down on the children, the baby, my friend, and me.

“What I really need is a garden here,” my neighbor said.

There clearly wasn’t much light in this Brooklyn backyard for gardens. I looked up at the tree, its trunk pushing up against gravity; its branches, fractals, spreading out over her yard and into ours. All that life lifting up and soaking in the sun.

“Roses would be lovely…some Belle Amour, Floribunda, and maybe the Tuscany hybrid. I should do dahlias too…I like those Labyrinths, maybe some Shooting Stars, and definitely Arabian Nights,” she trailed off.

I hadn’t looked at her, kept my eye on the tree as she talked.

Then she said, “The tree will have to come down.”

Six starlings swiftly flew from the branches, the boys got in a fight, and the baby started to cry.

That Saturday I heard the sound of the chainsaws wailing away at eight in the morning.

George was pissed. “What the fuck…”

I was already up with the kids, breakfast on the table and feeding Violet her oatmeal.

“What the fuck are they thinking on a Saturday morning? I’m trying to get some sleep. Jesus.”

“Oh, hey…the kids…” They were both looking up at their loud and annoyed father.

I tried to calm him down. “I know, I know! I think they’re cutting down that beautiful old maple.”

He looked at me as if I were stupid. “I don’t care about the tree. I care about my fu…my sleep.” He turned on his heel and spun out of the room.

The kids and I looked at each other. Everyone’s mouth open wide.

Then I heard the door slam. Still, I kept calm and continued to feed Violet, until I heard the shouting.

Standing on the sidewalk with Violet on my hip, and holding Jasper close to my other hip, I watched George cuss out Stan, my friend’s husband, who was cussing back at him. Next to Stan stood his wife. Her eyes glazed over, I could only imagine she was thinking of those roses and the Arabian Nights.

The men argued, the woman stared, the tree was dying, and the children were growing as I held them. A fierceness like a horse galloping through long grass passed through me.

“Come, Jasper, let’s finish breakfast. We don’t want to be a part of this.”

He looked up at me and nodded.

All weekend George’s loud voice rumbled and spread like a vine throughout the house as if the volume alone had the power to end all clashes, as if he were the arbiter of all that is just.

George didn’t win the fight, and the tree came down that Saturday; by Sunday evening all traces of its existence in the backyard were gone.

by M. Lea Gray | Aug 5, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

The lingering perfume of a million flowers is so thick in the funeral home showroom that invisible rose petals plaster the inside of my mouth. Navy curtains hang heavy and block out the daylight because it really is easier to mourn in controlled lighting without the distraction of bikes and buses and joggers living, fully living the way people do under the big bright yellow sun.

A salesman in the funeral home stands over Mom and me. He’s very sorry for our loss. He understands how difficult these decisions are, but does he actually understand? Has he ever watched someone die piece by piece, one day at a time, or is he like mostly everyone else who backs away because watching someone dissolve taints the memories, so friends and family, every single goddamn fucking person who said, Whatever you need, call, I’m here for you, is just a bag of hot air who I bet will show up at the funeral and mumble how they wish they could have done more. The salesman bows his head, so his shoulders swallow his chin, and in a short, sharp whisper, he calls the urn. Mom is holding a luxury vehicle like it’s some kind of exotic ship. The urn is stainless steel. It’s got that cold bluish tint, so it looks sterile. The salesman has a practiced sombre mask, and he knows exactly how long to keep a string of serious silence hanging between all three of us before he asks if we’re interested in knowing how much?

Mom’s laughter starts breezy and light, fluttering through the hushed whispers rising out of the clusters of people choosing between casket and cremation. Her laughter grows out of some mutated clump of cells the size of an orange pushing against her brain. Her laughter swells from breezy into a thundering boom that levels the funeral home showroom like a shock wave, and a woman pawing through swatches of silky casket linings staggers as if some invisible hand pushed her from behind. The woman clings to a man next to her, cowering from the invisible assault. The salesman chokes on a gasp, but he recovers his solemn seriousness and tries to redirect Mom and me back to the luxury vessel’s quality craftsmanship. He doesn’t miss a beat as he launches into reassuring us that the remains will be totally secure once the urn is sealed. The remains. The sealed remains. Mom’s laughter tapers off into a dry, hacking cough. Automatically, I pull a Kleenex out of my pocket in case her eyes start leaking, but it’s not her eyes this time and by the time I get the Kleenex twisted into bullets and pushed into Mom’s nostrils, three drops of blood are streaking down the potbelly of the luxury vessel. The salesman breaks his sombre mask and recoils at the sight of Mom’s blood. It’s probably more life than he’s used to.

A fresh round of hiccupping chuckles is building, and in a minute, hysterics will have Mom doubled over, clawing for air.

The clusters of people in the showroom slap their hands over their mouths. So appalled. So outraged, and my god, we should know better. We should know better! They can’t believe we’d steal their grief. They can’t comprehend this cruel invasion into their very private, very difficult, deeply personal moment, and what kind of people are we? We have no decency. And maybe we don’t have decency because that was one of the first things to go when the mutated clump of cells started pressing buttons in Mom’s brain, and pee dribbles turned to soaked pants and humiliation in the supermarket checkout line while she stood in a yellow puddle, when every single son of a bitch holding their jugs of milk and bags of potatoes, who sit at tables in her diner, her fucking diner!, and know her name and ask about the family, the kids, Any summer vacation plans?, backed away from us like they’d catch whatever she had. I’ll say it again, I bet they all show up at the funeral and mumble about how they wish they could have done more.

Mom flips open the urn, so her airy giggle rings through its hollow belly. She closes the lid and traps her voice like a songbird. I hope the luxury vessel seals her voice forever so I can press my ear to its stainless-steel body and listen to her laugh forever. Soon enough, Mom won’t bother anybody. Soon enough, Mom will be just a collection of fading memories.

“Is there a better time?” The salesman avoids looking at Mom. He pleads with eyes that beg me to get Mom out of the showroom because this is a place for the dead. Can’t I see that?

Mom’s laughter splinters, warbles, and swells into a lump she clears out of her throat like phlegm. “What’s the return policy?” Mom asks.

The salesman’s eyes crisscross from the question, but he tries again to regain control of the sale before the commission on this top-of-the-line urn slips out of his hands. He picks right up where he left off, and the cracks in his sombre mask smooth over, so once again, he understands how difficult this is for us, but “All sales are final.”

Bloody bullets of Kleenex hang from Mom’s nostrils, and no one in the showroom is even pretending not to stare. The woman from the earlier assault forgets her grief, forgets her weak state of mourning, and she rears up like a snake about to strike. The woman dares Mom to snicker just one more time, and she wags the swatches of silky casket linings like she’s threatening a bratty child who could use a good wallop to put them in their place.

Mom holds the urn up to her face, huffs hot breath onto her distorted reflection, and wipes away the streaks of blood with the cuff of her sweater. “Well, I can’t try it on,” she says.

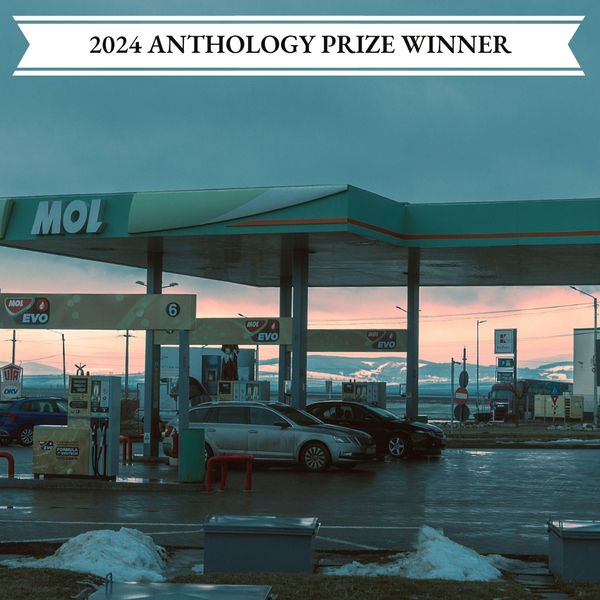

by L Mari Harris | Jul 31, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

I watch her pocket two Snickers bars while I’m ringing up the guy who always buys a can of Skoal and a tallboy.

His name is Billy. Nice guy, friendly. Works at the tire factory or the auto shop, I can’t remember which.

He’s watching the girl, too, as she heads to the front doors, the afternoon sun glaring on the cases of water bottles and the rack of sunglasses.

Billy says to the girl, “Hey, I saw what you did. Put them back.”

I wave Billy off and give her a look like I’m sorry we interrupted her day.

“It’s okay. Go,” I tell her.

Billy shoots me a look like, What the hell? I thought you were one of the good guys.

“She looks hungry,” I offer in the way of explanation.

“But stealing’s not right,” Billy says. “You should call the cops.”

By now, the girl has slipped through the doors, and we watch her walking along the grassy median that separates the highway. Semis and $80,000 Dodge Rams whiz by, spraying her with water that hasn’t drained off from last night’s storms.

I can feel Billy watching me watch her. “I’ve seen her before. Nothing good’s coming from the way she’s living,” he says.

“And we’re doing any better?” I say, somewhere between dead serious and a joke.

Billy shrugs, slaps a twenty down, tells me to keep the change. Tells me work’s been picking up lately, that it’s a good time in his life and he’s not messing it up again.

In this version, Billy shows up with some girl tagging after him.

Her hair and clothes are damp, like they’d been parked down by the river and out of nowhere she decided to jump in for a quick swim. Maybe they just met and she was trying to impress him. Maybe she slipped on a rock. Probably Billy told her, “Do this and I’ll love you forever.” Billy seems like that kind of guy.

Or maybe she’s his wife. She looks a lot younger than Billy, but what do I know? People can surprise you. They surprise me all the time. Like that woman who comes in wearing a business suit and heels, hair in one of those fancy chignons, and buys one pack of Swisher Sweets Minis, grape flavor, that she tucks into the bottom of her purse. You’d never guess it looking at her, fancy corporate woman like that, smoking cheap cigarillos on the sly.

Billy sees me looking at the girl’s wet hair and clothes. You’d think he’d offer up some kind of explanation, but he just tells her to go grab them a couple of candy bars, whatever looks good, while he points at the Skoal cans behind me.

He asks me if I’ve heard about the couple going around robbing convenience stores—In broad daylight. Can you believe the balls?—and I tell him the liquor store a few blocks over got hit last night.

“No shit?” Billy says. “Changing up their MO. That’s smart.”

The girl shows back up and puts two Snickers bars down on the counter.

Billy pulls a twenty out of his shirt pocket. “Yep. Keep them guessing. That’s real smart.” He asks the girl, “Hey, don’t you think that’s smart?”

“I guess,” she says, not taking her eyes off the Snickers bars.

“You guess?” Billy looks at me like he can’t believe he’s having this conversation. “You guess? Smart and sly’s where it’s at. How many times I gotta go over this with you?”

This is the version I tell the cops:

He pulled a gun on me, not the other way around. I lunged over the counter when I saw that gun pointed in my face, grabbed his arm and we wrestled over it, because I wasn’t about to die making $12 an hour where people are always shoplifting shit anyway, and besides, who am I to know what someone’s going through, why they feel the need to steal candy bars or tallboys, maybe they’re hungry, or maybe they had a bad day at their own shitty job.

What? Yeah, I’ve seen him in here before, he comes in a lot, maybe he’s been casing the place; sometimes he comes in with a girl who always looks like she just rushed out of the shower, sometimes not, guy’s always friendly.

Yeah, could be. Now that I think about it, maybe too friendly. And she never talks, but today she kept yelling Don’t you hurt him! and I’m thinking what a weird thing to say, he pulled a gun on me. And then I notice they both have the exact same hazel eyes, and it hits me, who the hell brings their kid along to a robbery, and then I feel this pain shoot up my arm, all the way to the shoulder, and I see his mouth moving, but I can’t hear him, and then my ears pop and I hear screaming, and he’s looking down at the floor, up at me, down at the floor, up at me, then he’s running out the doors, then you guys show up and all I can do is point toward the highway, and I can’t remember the girl running after him, you’d think he wouldn’t leave her behind, right? His own daughter?

No, sir, never have. Nothing good comes from having one around. Only one time I’ve ever held a gun. Thrust in my hand by my dad, uncle, one of Dad’s friends? I can’t remember anymore. Only thing I remember is how cold and heavy it was, how it wasn’t at all like I’d expected, how surprised I was. It felt just like that.

Recent Comments