- (Tommy Dean) I love the mix tape/Album format of the Chapbook. Especially the run or reading

times next to the titles in the Table of Contents! Where did this idea come

from? How does it influence or enhance the reading experience?

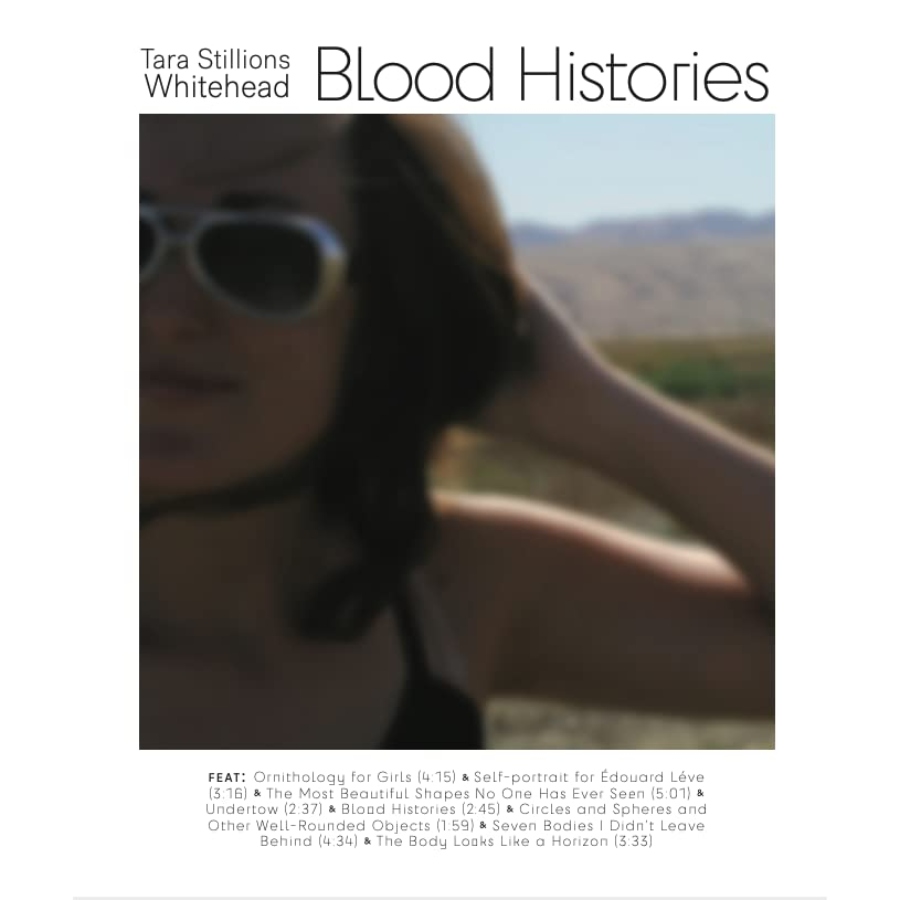

(Tara Stillions Whitehead) I’m glad you like the album concept—I really have Galileo Press editor Barrett Warner and book designer Adam Robinson to thank for that. In preparation for the release of Blood Histories, I created two book trailers. The first used a postcard-themed visual style with me reading an excerpt from “The Most Beautiful Shapes No One Has Ever Seen.” That story, which involves a woman grappling with alcoholism and losing her mother to terminal illness, incorporates lyrics to songs that I associate with the Southwest and other barren spaces I’ve lived in or traveled through. When Barrett saw the trailer, which included some photos I took of a friend in the desert about 15 years ago, it clicked for him (or at least, that was my perception of it). Music references aside, the book is very lyrical. The title story is anthemic, a nod to female musicians who dominated in the 90s when I was a teen, and Barrett believed it, along with the other dispatches, constitute an album more than a book. He relayed this to Adam, and the two made magic. Blood Histories is exactly what it needed to be, and I think this is an example of trust in others and the collaborative synergy makes better art.

- (TD) How important is it to your writing to take on different point of views? How does

this conflict with your CNF? Are fiction and non-fiction at odds with each other? Is it the point of view, the choosing of a character, that delineates the forms?

(TSW) The attempt to embody another perspective is an attempt to empathize, and empathy helps us create dynamic characters. How well we execute is up to the reader.

I don’t consider fiction and nonfiction at odds with each other, but I do think it is important to consider the ethics involved in setting up reader expectations through categorizing a text as fiction or nonfiction/CNF. I have published work as fiction when it could have been CNF, and I have published CNF that leans on ambiguity. I do this in “Self-Portrait for Edouard Léve,” which appeared as a prose poem in Gone Lawn, issue 37. It is likely the most vulnerable work I have ever written. But one has to ask, where is the threshold that makes it a poem? A biography? A dialogue with the late Léve? What makes it true?

Fact: “I do not recognize the scent of a tiger, but I have eaten glass and phencyclidine; I fear sudden thirst, and I know where to find drink, how to use it against myself to end the world.”

The general statements “find drink” and “end the world” are where I’ve blurred the lines. Whose world? What drink? Would it be better to come out and say a shard of glass in a salad a friend served me nearly killed me? That I am a recovering alcoholic and will, if given the chance, destroy myself with it? Omission serves a purpose here. Using concrete language that is open and allows for exploration places the onus of truth on the reader who, if presented with a piece categorizes as nonfiction, is programmed to read for “facts.” I addressed this in a panel on flash memoir last spring, where there were many questions about categorizing work. For me, truth and facts are not the same. However, the world we live in, obsessed with empirical proof, uses the terms interchangeably.

I consider my purpose with a piece when deciding how to submit it/designate it for publication. Because we use genre to assist us in our approach to reading and making sense of a text, I have to consider what the audience’s expectations are and appeal to them ethically. I do not present truth as fact; I do not presume nonfiction should avoid ambiguity or abstraction.

I think a lot about the first lines in John Prine’s “Angel from Montgomery”: “I am an old woman named after my mother/ my old man is another child that’s grown old.” Early on, people thought Bonnie Raitt wrote the song. She is a woman. Singing a song about being a woman. However, Raitt was not an “old woman” when she covered Prine’s masterpiece. The word “old” becomes an abstraction for me. Old how? Old soul? Old-fashioned?

When I hear John Prine sing his song, I believe he is that woman, that soul. I refuse to accept that he is not in the woman in the kitchen, hearing the flies buzzing, wishing for “one thing” he “can hold on to.”

I have strayed from your questions. What I think we can learn from the folks who spin yarn into gold is that the writer’s purpose is central to the genre designation. John Prine was writing another song about being tired of the same old shit, but he was also rewriting Charles’ Baudelaire’s “Windows” (1898), which imagines the agony of a woman who “is forever bending over and never goes out,” her life lonely, repetitive, exhausting. Baudelaire writes:

“Avec son visage, avec son vêtement, avec son geste, avec presque rien, j’ai refait l’histoire de cette femme, ou plutôt sa légende, et quelquefois je me la raconte à moi-même en pleurant.”

Did Prine invent others’ stories to help him “suffer in someone besides [himself]” (“souffert dans d’autres que moi-même”)? If not, the songs allow me that privilege.

- (TD)These characters, are tied to natural world, to the beauty: the danger. How do these

sensual details of the natural world work to help you draft? Or are they found while

revising? If the average person looks past nature is fictions job/function to make them notice?

How do you decide what’s worth noticing?

(TSW) I enter a story through setting more often than character when I’m in generative writing mode. I usually need to sense the space before I can populate it. “Ornithology for Girls” began in an orchard. I smelled the dry grass. Tasted the winter mud. Then, a flash of red. A robin. A mother. Sick as the grass. Removed from the mud, the early disease.

Once I sense a place and populate it, I ask, “Why here, and why now?” Those questions usually lead me to “what’s worth seeing and smelling and tasting and hearing here?” I like to employ the senses that are less obvious or more difficult to translate into words. Sound and smell and taste get the reader emotionally “plugged in.” It’s even better when you can use literal representations instead of figurative language. A room can feel too small for the character or it can be too small. If I make it too small, I can have a lot of fun with the character bumping into things and the conflict arises out of the diegetic world as opposed to an authorial metaphor—which works, obviously. A lot of people write that way. But I love to use setting as a character with edges that can draw blood, not just give the impression of danger.

I teach a digital media senior seminar course, and right now, students are creating a multimodal scavenger hunt project that uses the senses to help recall memory. One of their “rooms” involves smell, and they have been researching which scents have the strongest emotional associations with childhood. I find I try to do the same with my writing. What does winter taste like? What emotion arises when I cross the smell of chaparral with sweat? How does this character experience chronemics? To secure full investment from the reader, I have to take them to the desert, to the orchard, to the bar, to Las Vegas, to their knees. I have to use all of the senses, and I have to be economical.

- (TD) How do you find the seams in realism to open up to fabulism? What unlocks this door while you’re writing?

(TSW) I was exposed to a lot of hybrid genre writing during my time in grad school. I took courses in prose poetry with Marylin Chin and explored subversion through indeterminate texts with Harold Jaffe. I read verse poetry, narrative essays, compressed fiction…really, anything I could get my hands on—Milosz, Celan, Lispector, Borges, Davis, Simic, Marquez, and Szymborska (to name a few favorites). I also read and fell in love with Annie Proulx, who used the Wyoming landscape as a portal to bestial mythologies of the 20th Century frontier. In fiction workshop, Katie Farris introduced me to Kate Bernheimer, who led me back to the fairytale, and from there, I started discovering troves of authors who give these playful forms dark, subversive looks.

“Opening up” to fabulism from realism is something I think Kurt Vonnegut did so well, and any time I am looking at an opportunity to transition a story into another register, I think, “WWKVD?” I’ll probably die alone on this hill, but Breakfast of Champions is one of the best books on the human condition ever written. It’s the perfect mashup of satire and folklore. Vonnegut presents a new fable, fairytale, historical retelling, or sci-fi story every five or six pages, and all of them add up to the best ending in all of literature: a man (writer) realizes that God exists—life matters!— and his one request to the Creator of the Universe is “Make me young! Make me young!”

- (TD) How do you approach creating metaphors? For example, “a girl who hides shame the way mothers conceal the bruise on an apple, it decaying softness tucked hard into the palm.” Is there something hiding in an image like this?

(TSW) This is my simile pretending to be a metaphor because I do not like similes. There is a lot going on in this metaphor. The book deals with mother-daughter relationships, inherited identities, misrepresentations, societal expectations, and the power of defiance. Food offerings are common conceits in fairytales, as are mother-daughter relationships, and most of these intersections involve maternal dishonesty (see: Snow White, Hansel and Gretel, God’s Food, etc.). So at the level of artifact, the symbolism conveys clear but transient meaning. The logic of the metaphor is what is being compared. A bruise on an apple cannot be hidden, only concealed by the offering hand, which implies that the girl cannot hide her shame, only conceal it strategically until she is revealed, discovered, eaten. I am a mother whose children used to eat the apple whole, without inspecting it. They trusted me. At some point, they discovered the texture and taste of the bruised apple was not to their liking and now eat around it. They ask me to pare the overripe patches out of the banana, but sometimes I can get away with handing it to them uninspected. Until they find the offending spot and give me that look, the “you tried to deceive me” look. The girl with the shame is playing the role of the mother who deceived her.

A metaphor should not make the abstract more abstract or make something clear more opaque. I enjoy it when someone places two concrete elements within the context of a metaphor. Juxtaposition alone is pretty powerful. That’s my personal preference.

- (TD) I’m wondering about your relationship with music? A lot of these stories have lines that feel like song lyrics. Do you listen to music as you write?

(TSW) Blood Histories is technically my second book, but it is the first to be released. The Year of the Monster, a full-length collection of traditional and hybrid stories, will be released next year, and I would say that the lyricism is 150% stronger in this second (first?) book. There are a lot of reasons for this. One of them is that I got sober. This was a year or two before I started querying for TYOTM. During that time, I couldn’t listen to music because it took me to places I didn’t want to revisit. I didn’t know how to have emotions when I quit drinking because I had anesthetized myself for so long. A CSNY or Sublime or PJ Harvey song would make me lose it. I didn’t know how to feel the feelings that music made me feel. I would drive 32 miles to work every day in silence because I couldn’t even handle the radio. That was hell for me. Music is transportive, and without it, I felt stuck in this oppressive reality of having to deal with life on life’s terms, without a drink to help me cope (not that I ever had only a drink). I had no coping mechanisms. Music eventually brought me back to writing, but it was a journey.

I sometimes write to music now. Usually, that occurs when I am working outside of the house. I like to write in crowded spaces, away from my vacuum cleaner and the piles of clean laundry. I’ll typically write for an hour or two with the same 12-13-song playlist on repeat.

- (TD) Can stories or narratives save us? Is there a function beyond entertainment?

(TSW) Each story I read is a tool that goes into my toolbox. I use some more than others, and there are those I don’t know what to do with, but they go into the big drawer on the bottom, just in case I one day figure out how they can help me. By virtue of its conception in another human being’s mind, a story can, at the very least, alleviate my loneliness. Even if it’s a bad story, knowing someone was on the other end, creating and attempting to connect, reminds me that there is more to a story than the inciting moment and the reversal of fate.

Very good stories affect change. In the reader, across cultures. Sometimes these good stories get a lot of mileage on main. A director I’m producing a film for keeps referring to my work as literary and “emotional.” It’s his way of differentiating it from “mainstream books.” I think it’s also his nicer way of saying my writing does not appeal to a wide audience. My mother-in-law reminds me of this, constantly. When she read Blood Histories, she told me, “I didn’t understand any of it. Not a single word.” At face value, someone might think this is a directed insult—how could she not understand a word?—but knowing my mother-in-law, whom I love very much, I understood the comment within the context of what she likes to read, and she isn’t my audience. I’d love to think my writing could provide universal tools, but I’m okay with it having the ability to move a small number of people in ways they are still trying to articulate long after they put the book down. Many people have reached out and thanked me for writing this book. Some of them feel it has something to say. Some of them were entertained. The fact that anyone has given their time or money to stuff that came out of my head? I should be so lucky…

- (TD) Your stories are so sensual, not just visual, but a feeling of being a body—in danger, peril, seeking safety, growing, maturing, fighting. How has your film career helped with your writing?

(TSW) I’ll address these two topics in reverse order. Much of my film and television career occurred before significant events in my life that gave me purpose. I went to film school, the best at the time. I worked over one hundred episodes in production, first as a production assistant, then as an assistant director. When I landed at Warner Bros. with the idea that my job would lead to writing opportunities, I was hungry and desperate to get out of production. If you look at what is going on in film and television production today, you will see that not much has changed in terms of quality of life on set. IATSE is about to go on strike, and the stories they publish anonymously on their social media pages are horrifyingly familiar. I wrote about the sexual assault that I endured and the disturbing way it was “handled.” I would never say that the trauma was necessary for me to have a good life (because my life is good today). Trauma, sexual violence, emotional abuse—none of that is necessary or okay. However, choosing to leave the industry for a near decade was the best decision I could have made. As I slowly move back into visual storytelling (I produced a web series in 2019 and am currently a producer on a short film), I am hyperaware of my role in ensuring the crew is treated well. I would hate to think that we are “making art” at the cost of someone’s health and livelihood, which is, unfortunately, the culture of the industry at large.

Film and television are topics in my writing—celebrity worship, the fetishization of violence and addiction, the lack of ethics and outright abuse of people involved in creating shows streamed all over the world—and have a hand in the shape of my stories. TYOTM has a lot of hybrid script, alongside many industry stories. My writing overall is stylistically visual. That, I am sure, comes from working in the visual medium.

Working in the visual medium has always attracted me because of the haptics involved. I’m talking about physically maneuvering a camera, a light, a body through physically represented diegesis. Writing has a haptic quality. I write by hand. I keyboard emotions. The .2 in THX’s surround sound formats triggers my fight or flight. The vibrations in a textual world have the capacity to trigger my adrenaline. When I write, I want to go for immersion and economy at the same time, and that’s where the haptical approach—I want to TOUCH the reader in this specific way with this specific word—comes from.

BIO:

Tara’s writing has been published in or is forthcoming from various award-winning journals, magazines, and anthologies, including cream city review, The Rupture, Fairy Tale Review, Gone Lawn, PRISM international, Chicago Review, Pithead Chapel, Jellyfish Review, and Monkeybicycle. She is Assistant Professor of Film, Video, and Digital Media Production at Messiah University, where she is also faculty for the renowned Young Writers Workshop, and has given public lectures on monsters, media, and film.

Tara’s writing has been included in the Wigleaf Top 50, has been nominated for Best of the Net, the AWP Intro Journals Award, and a Pushcart Prize. She is the recipient of a Glimmer Train Press Award for New Writers. Her hybrid chapbook, Blood Histories, will be released by Galileo Press in July 2021, and her full-length collection, The Year of the Monster, is forthcoming from Unsolicited Press in September 2022.