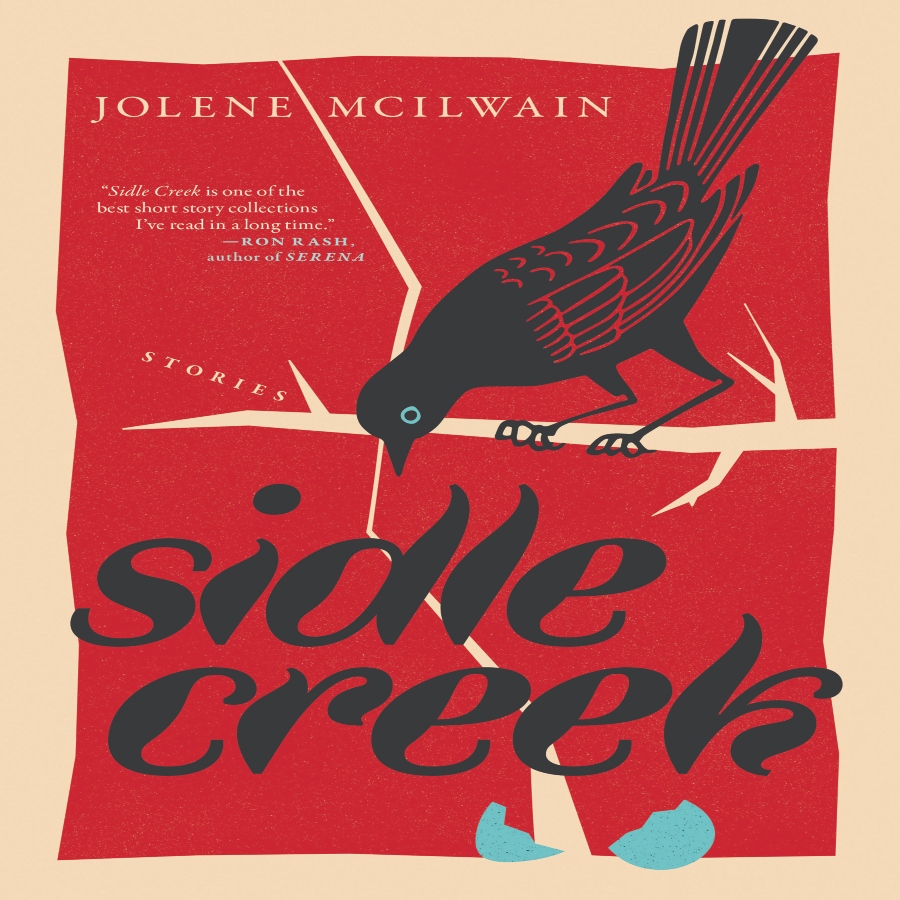

Jolene McIlwain’s Sidle Creek, a collection of flash and short stories, is amazingly balanced between characters we care about and the joy and conflict in the natural world. This book will take you into the heart of the natural world, where it’s easy to imagine the smell and the touch of flora and fauna. In this book, readers will find fully rendered stories of the power of staying, of how nature can sear or smooth, and how people want to do their bests but often fall short in spectacular and simple ways. The mountains and valleys that these characters face are more than mere metaphors in these stunning stories.

Tommy Dean: What are your favorite things to write about? Those topics or items you can’t stop thinking about!

Jolene McIlwain: In SIDLE CREEK, I set stories in my favorite places, the workplaces of rural areas and small towns: the county hospital X-ray department, the favorite local diner, sawmills, dive bars, bait shops, on construction sites, rural letter carrier routes, traplines, and farms. My writing seems to always veer into themes of class, neglect, loyalty, complicity, unexpected human connections, and always the natural world.

Also, I can’t stop thinking about “the economic colonization of rural America,” as writer/activist Wendell Berry and others have dubbed it, which creates subsequent misunderstandings and clashes between rural and urban communities. So I like to write with those clashes (and potential connections) in mind.

TD: What’s your favorite point of view? Why are you drawn to this particular voice/perspective?

JM: I have two favorites. I fell in love with plural first person POV when I read William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily” back in college and have been experimenting with this POV ever since.

My second choice is definitely close third person, or free indirect style, which works best when I need to compress information about a character when I want to show personality through those things the character chooses to notice, as well as the words they naturally use to describe their worlds. I’ve learned a lot about free indirect style and indirect interior monologue by analyzing Alice Munro’s short stories. I like how James Woods explains this technique in his book, How Fiction Works.

One POV I have trouble writing—but I’m really pushing myself and working on it—is second person, and one of my favorite second-person stories is Ashleigh Bryant Phillips’s “Charlie Elliott” in 3 A.M. Magazine.

TD: What’s your favorite craft element to focus on when writing flash? Is there an element you wish you could avoid?

JM: I like to avoid titles!

I focus a lot on diction in all of my writing. I both love and worry (probably too much) about matters of diction/jargon choices. How will a reader interpret/“feel” my work when they see words they do (and don’t) recognize? Should I take the time to explain rifling? A face boss? A hysterosalpingogram? A diversion ditch? If I do add explanations, I add words to my limited word count.

Composing flash, however, forces one to focus on matters of concision, audience, and—specifically for me, an Appalachian blue-collar writer—on what or whom may be left out, what or whom may be prioritized, recognized. Two examples of what I’m getting at can be found in my pieces—“Searching for Stones” previously published in Flyway Journal, and “The Less Said,” which appears in SIDLE CREEK but was previously published in a slightly different form in the New Orleans Review—where I’ve used a lot of x-ray tech-speak and large-game-hunter-speak to best illustrate the POV characters’ mindsets. I’ve also studied my favorite contemporary writers to see how others have traversed this dilemma and made engaging, thought-provoking art from it, as in Kristen Arnett’s story “Gator Butchering for Beginners.”

For a long time, because of my past work in the medical field and my eagerness to write about those settings and experiences, I struggled with decisions on when to use laymen’s terms v. medical terms. But I always try to remember that Donald Hall, when I interviewed him long ago at a poetry conference, agreed that medical terms are also melodic, so lyrical, and must therefore be included in our poetry and prose. So, there will always be decisions to make: Do I use the angler’s colloquial jargon, the coal miner’s diction? Do I have the right to offer no explanation for these words? What’s most exciting to me is that the use of specific diction, familiar or not, could perhaps broaden the experience for the reader or start conversations.

TD: How do you know when a story is done or at least ready to test the submission waters?

JM: I have my computer read it back to me in its “robot voice” in the “read aloud” function. This bland tone really amplifies the flaws in syntax and typos, and if it actually sounds pretty good and doesn’t embarrass me too much, it may be ready to send out! Or maybe not. (I never really know when it’s ready.)

TD: When looking for places to submit your flash, what are your priorities for finding a good home for your work?

JM: I have to love what the journal is publishing. This makes submitting tough, though, due to my strong inner critic. Does my work rise to the level of what such-and-such journal is publishing? Also, I love to read work written by the journal’s editors and notice how their work speaks to me in some way. For example, I fell in love with Michelle Ross’s stories and knew immediately that I had to send my work to the journal where she’s fiction editor, Atticus Review. And, as I imagined, she took great care with my story and made it so much better!

TD: What do you know now about writing flash or other forms that you wished you had known from the beginning?

JM: I wish I had known more about how to be strategic with tonal shifts. I’m still learning that by studying one of the masters of tonal shifts in flash, Kathy Fish.

TD: What resource (a book, essay, story, person, literary journal) has helped you develop your flash fiction writing?

JM: I’ve learned a lot from flash fiction anthologies: Sudden Fiction, Best Sudden Fiction, and Best Small Fictions, as well as craft guides, such as The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Fiction. One book that I’ve used for all fiction lengths is Margot Livesey’s The Hidden Machinery. I’ve worked closely with Sherrie Flick, Nancy Stohlman, and Kathy Fish, three amazing flash writers.

Some writers who have influenced me most actually come from other genres. The poet, Jane Kenyon, seamlessly merges the natural world with tough, emotional, large life issues. The playwright Terrence McNally’s work taught me so much about voice and form. Annie Proulx packs so much description into her short stories while also leaving so much out, which shows a trust of her reader. Kent Haruf’s novels are spare and brilliant, Chelsea Bieker’s descriptions and dialogue are incredible, and Faulkner, of course, has this amazing command of specific language and POV, as do four of my favorite of all time contemporary writers, Jeannette Winterson, Louise Erdrich, Dorothy Allison, Toni Morrison.

I also love reading for jmww journal and working with my fellow flash editors—they teach me so much.

TD: Your short story collection, SIDLE CREEK, soon to be published by Melville House, includes traditional-length short stories as well as one that’s almost 11k and several flash and micros. How did you decide which stories to include, and were you concerned about the varying lengths of stories and how to order them for the best overall reading experience?

JM: My agent found me through my very short fiction rather than my traditional-length pieces. She’d seen my micro “Drumming” on Cincinnati Review’s online miCRo selections and contacted me through the editor there. When I sent the first version of my collection, SIDLE CREEK, to her to see if she’d want to represent me, it included about half of the stories it currently holds. Some of her favorites were the shorter pieces, so when we were preparing the collection for submission to publishers, we added even more, shorter ones.

I was unsure how to order them and referred to an essay by my mentor, David Jauss, called “Stacking Stones.” I always thought of the stories in terms of content more than length. I also considered the time spans for the stories—a few flashes covered a day or just a few hours, while others covered decades. And, no matter the length, I was working in some tough emotional terrain, including stories about stillbirths, infertility, underground fight clubs, poverty, and hunting fatalities. Not easy material. I tried to consider how the reader might react emotionally after each piece.

Then, in my discussions with my editor at Melville House, we talked about how the shorter pieces enhanced the overall themes, offered a further sense of place, and were a sort of connective tissue as well, making SIDLE CREEK feel more whole. It was wonderful to see my tiniest (in length) stories holding their own, with the longer ones weighing in at 9 and 11k.

TD: What’s your favorite way to interact with the writing community? Do you have any advice for writers trying to add to their own writing communities?

JM: I am part of both online and in-person writing groups that meet regularly, and that has been extremely helpful. If that’s not something you can do, I’ve used Twitter and Instagram to interact with flash fiction writers. It’s a very supportive community. I also feel it’s most important to attend readings, in person or online—so many of these events can be found through universities and small independent bookstore’s social media pages, as well as through online literary groups and collectives.

Finally, volunteering to read for a journal can teach you so much about the behind-the-scenes work that goes into discovering and supporting writers, as well as the revising, editing, and nominating processes. It can help you feel you’re not swimming alone in this whole writing waterway.

**

Jolene McIlwain’s work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and appears in numerous online and print literary journals including West Branch, Florida Review, Cincinnati Review, CRAFT, Smokelong Quarterly, New Orleans Review, LITRO, and more. Her work was included in 2019’s Best Small Fictions Anthology and named finalist for 2018’s Best of the Net, Glimmer Train’s and River Styx’s contests, and semifinalist in Nimrod’s Katherine Anne Porter Prize and two American Short Fictions contests.

She’s received a Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council grant, the Georgia Court Chautauqua faculty scholarship, and Tinker Mountain’s merit scholarship.

Her debut, SIDLE CREEK, received a starred review from Publishers Weekly, and Shelf Awareness calls it a “riveting debut collection” and “a rare gem, a compelling blend of nature and humanity perfect for fans of Barbara Kingsolver’s Prodigal Summer and Daisy Johnson’s Fen.” Ron Rash, bestselling author of Serena calls SIDLE CREEK “one of the best short story collections he’s read in a long time.”

Jolene’s taught literary theory/analysis at Duquesne and Chatham Universities, and she worked as a radiologic technologist before attending college (BS English, minor in sculpture, MA Literature). She was born, raised, and currently lives a small town in the hills of the Appalachian plateau in western Pennsylvania.

**

Tommy Dean is the author of two flash fiction chapbooks and a full flash collection, Hollows (Alternating Current Press 2022). He lives in Indiana, where he currently is the Editor at Fractured Lit and Uncharted Magazine. A recipient of the 2019 Lascaux Prize in Short Fiction, his writing can be found in Best Microfiction 2019, 2020, 2023, Best Small Fictions 2019 and 2022, Laurel Review, and elsewhere. Find him at tommydeanwriter.com and on Twitter @TommyDeanWriter.