When We’re Empty Of What We Are Designed To Hold

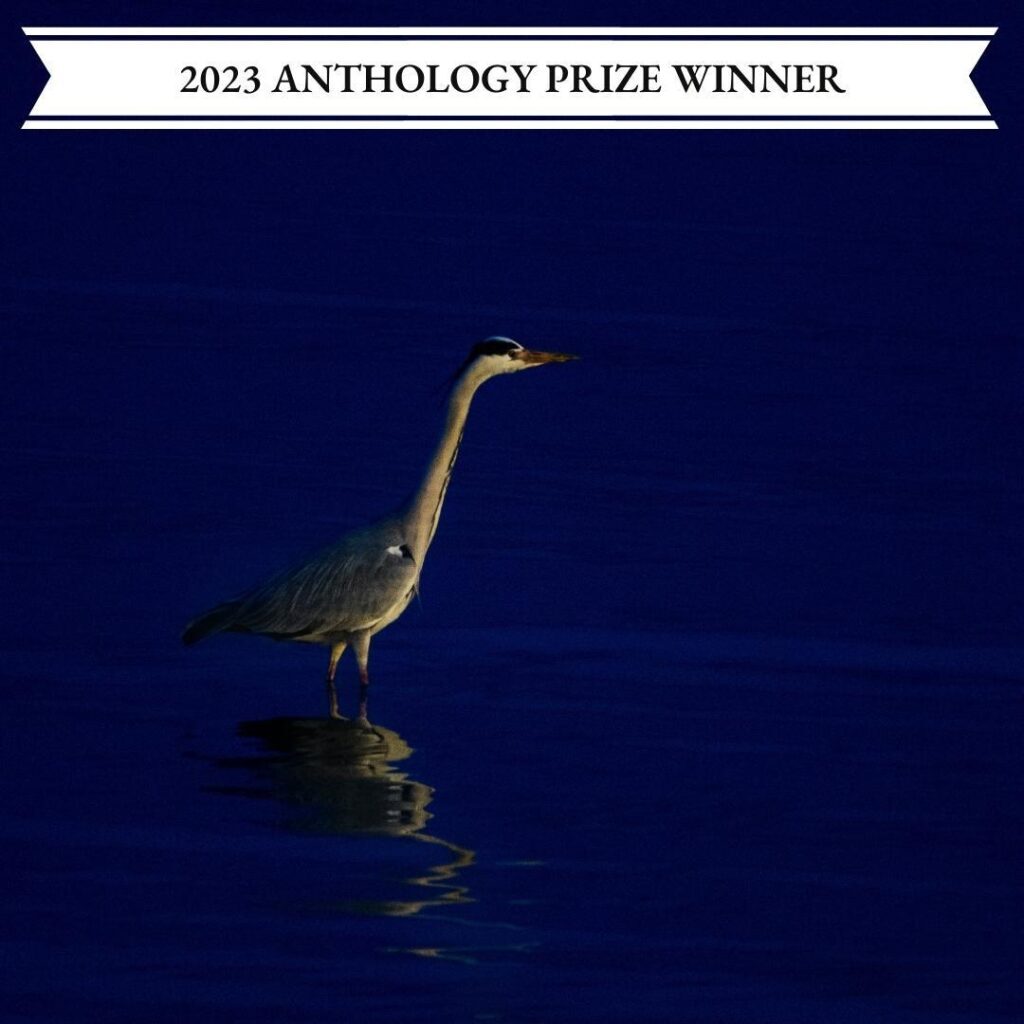

One Sunday morning, I wake up to discover that both of my daughters have turned into birds. The younger—a tow-headed chatterbox, always sidling up to me when I baked, eager to add a spice of her choosing to the recipe—is a great blue heron stalking around the kitchen on reedy legs, probing the drain for fish. The oldest—wise beyond her years, sarcastic, and often mired in thought—is a regal swan, aloof in the living room. I discover our dog on the landing, covered in piss, shaking and whining. My husband has left coffee on my nightstand, still steaming, beside a note: gone for bird seed.

I cup my mug in both hands, letting the heat leach through the ceramic clay into my palms. The pain of the heat centers me. I do not know what to do with two bird-daughters, but instinct tells me I need to be fully human right now. Grounded, present. Other new-agey aphorisms. I consider doing child’s pose, but the fetal position feels more appropriate. I spend a good half-hour curled like a shell on the floating island of my mattress. Breathe like unpredictable surf, doing its in-out thing. The featherlight clicks of talons on the linoleum floor seep under the door, sending panic into my brain. Meditation feels useless when surrounded by girl-bird sounds.

Before today, I would’ve considered myself an amateur birder. I logged bird sightings into my Audobon app as I walked through the park. Got a little thrill when spotting red or blue plumage. But it’s clear I’m out of my element. It’s 9:30 AM, and I realize it’s well past breakfast time. I cautiously peer around the door frame into the kitchen. My heron-daughter is quiet, perched on one leg; she has given up her attempt to forage in the disposal. She studies me with a flat yellow eye. Her beak is the shape of a blade. I sidle up to the cabinet, back pressed to the door, and slowly creep a hand in to grab a bag of bonito flakes. I dump them out onto a plastic fox plate from her toddler years, a nostalgic place setting I could never part with. The plate she used to lick the remnants of cake crumbs from on her birthdays. I set it on the floor and sneak out of the room. I can’t witness this new avian form of eating, with no tongue or teeth in sight. I tiptoe to the living room against the soundtrack of keratin blades pecking plastic.

Swan-daughter is patiently preening, nuzzling through her white feathers, waterproofing her wings, even though the best I could offer her at this moment is a baby pool that has collected dead leaves in our backyard. Or she could join the bird-shaped paddle boats on Stowe Lake, where her glorious plumage would steal the show.

I slowly unveil a piece of bread stolen from the kitchen before I flee. I shred it into small mouthfuls and scatter it in front of me, breathing quietly as she waddles over to eat. She is dainty and careful in her consumption; she doesn’t look at me, but I can tell she is as aware of my presence as I am of hers. Still studious in her new form. I remember reading, once, how aggressive swans are about protecting their nests. One man is rumored to have drowned in a swan attack, a merciless mother beating him relentlessly when he waded too close to her hidden eggs. I am keenly aware of swan-daughter’s sturdy frame, her long, muscular neck. The white feathers a false sense of security, my swan-daughter dressed as surrender. Even as a human, she outgrew physical intimacy quickly; hugs and cuddles turned into squirming away, a shoulder lent for a quick embrace while still leaving bodily space between us. I simultaneously want to stroke her back and flee to “buy bird seed”.

But I’m nailed in place, watching my love change shape into something interspatial, interspecies. My heart downy as velvet. Heron-daughter approaches us both. We stand as a trio, observing one another, balanced like a three-legged stool. I outstretch my hands, crumbed from the bread. I’m reminded of religious iconography, minus the gentle dove or goldfinch. I close my eyes. The funk of feathers fills my nose. I can feel their mouths investigating my palms, equally cautious. All of us, navigating this new relational space. They are moving through the world as reimagined creatures, divine. Leaving me—and my arms, bare of all but freckles and blonde hairs—behind.

As though without thinking, I open the largest window of the living room. Swan-daughter has to bow her head slightly to get through, but she is quickly gone, as I always feared. Her leaving, in the moment, takes on a quality of quartz; held at one angle, it is opaque, a punctureless grief. Tilted, it becomes clear, something that welcomes and reflects the light.

Heron-daughter perches on the sill for a moment, as though considering how I might be feeling. My youngest, my shadow, who would part parents at the playground like Moses parting the sea, always looking for me. She cocks her bird-head in my direction. Her expression reads as apology, or perhaps I’m anthropomorphizing. Then she stretches neck, body, leg, and wing, a giant being. She swoops down the street. Turns the corner where I can no longer see her. I shuffle to the door of their shared room, now childless. A few down feathers nested in the blankets. I plant my feet on the floor and then my palms. Knees perched on the back of my arms, I dip my head, complete a crow pose.

After a time, the doorbell rings. I expect a bird-daughter returned, or perhaps a husband, replete with seeds. But when I open the door, I am greeted by a big blue egg, 3 feet in height. We consider each other in silence for a moment, and then I invite her inside.

Quinn Rennerfeldt is a queer parent, partner, and poetry/prose writer earning her MFA at San Francisco State University. Their heart is equally wed to the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. Her work can be found in Cleaver, Mom Egg Review, SAND, elsewhere, and is forthcoming in A Velvet Giant and Salamander. They are the recipient of the 2022 Harold Taylor Prize, sponsored by the Academy of American Poets. Her chapbook Sea Glass Catastrophe was released in 2020 by Francis House Press. They are the Editor-in-Chief of Fourteen Hills, a graduate-run literary journal with SFSU.

Submit Your Stories

Always free. Always open. Professional rates.