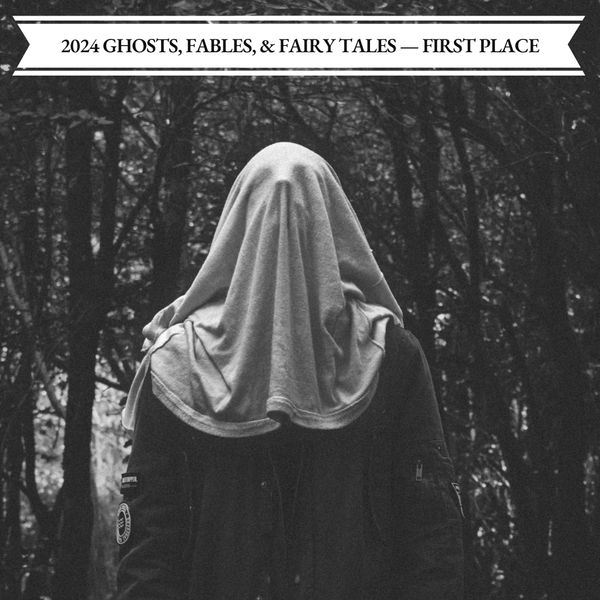

There are six of them. No, seven. They cycle out of the tower and into the night, following their headmistress. Their headmistress wears a habit. The girls wear cloaks, cloaks to hide their hunger.

I cannot tell you where they are going, but I’ll tell you this: they are following a man—a man in a suit, cufflinks, and dress shoes, a man on a bicycle. They trust the man, but the man should not trust them. A pack of young girls is not to be trusted.

But a pack of young girls has to eat. They have not eaten in weeks. Their headmistress is in charge of feeding them, and she has not been diligent.

I don’t like when they have mustaches, one of the girls whispers. The hairs get caught in my teeth.

I’m too starved to care, says another.

This is a farce, says a third. He is old and ugly and drooping in all directions.

The girls cycle to the river. They eat the man, but he is not enough. They eat their headmistress, too. One of the girls coughs up her habit, the fabric damp and clumped and bloodied.

We’re gluttonous, says the girl, tossing the habit into the river.

We ought to drown ourselves, says another. As penance.

She wasn’t our mother.

She was like a mother.

Our real mother is gone.

Gone because we ate her.

The girls think back to their mother, whom they ate. She tasted better than anything they’d ever known. Like moonlight and shadows and cardamom. They’d had to eat her. Because of circumstance. Because of growing up. Because they were so so hungry, and their mother wouldn’t let them out of the tower.

We ate our mother! one of the girls cries. They’re in the river now, all of them, deep in remembrance, letting their bodies float downstream like dead fish.

We ate our father, too, another reminds them. And the baby. And the chef. And our lover.

Our lover was sour.

Our lover was curdled milk.

The baby was an accident!

Mother placed the crib right beside our bed, they remember. The baby practically crawled into our mouths!

Made our mouths taste of childhood, and the ocean, and millions and millions of years––

We had to swallow it.

The girls whimper, snivel, swallow, gulp down river water.

This hunger, they lament. Will it never end?

They sob, tears filling the river, raising it. The current pulls their bodies, down and down, sometimes underneath, but always back to the surface, until the water shallows, and the pack washes up on its shore, hands linked, eyes puffy.

I feel a lot better now.

Yes, they all agree, standing up, arms still linked.

We ought to find our bicycles.

And our shoes.

Our feet are going to be terribly dirty.

We’ll wash them when we get home.

Soon, the girls are skipping, hand in hand, some giggling, cloaks dry and billowing in the

nighttime breeze. They return to the tower and tuck each other into bed.

Was the bed always this small? they ask one another.

Was the tower always this narrow?

The girls clutch their stomachs, which rumble like thunder. They are not satiated. They move their heads side to side, taking each other in—the supple skin, the tender flesh.