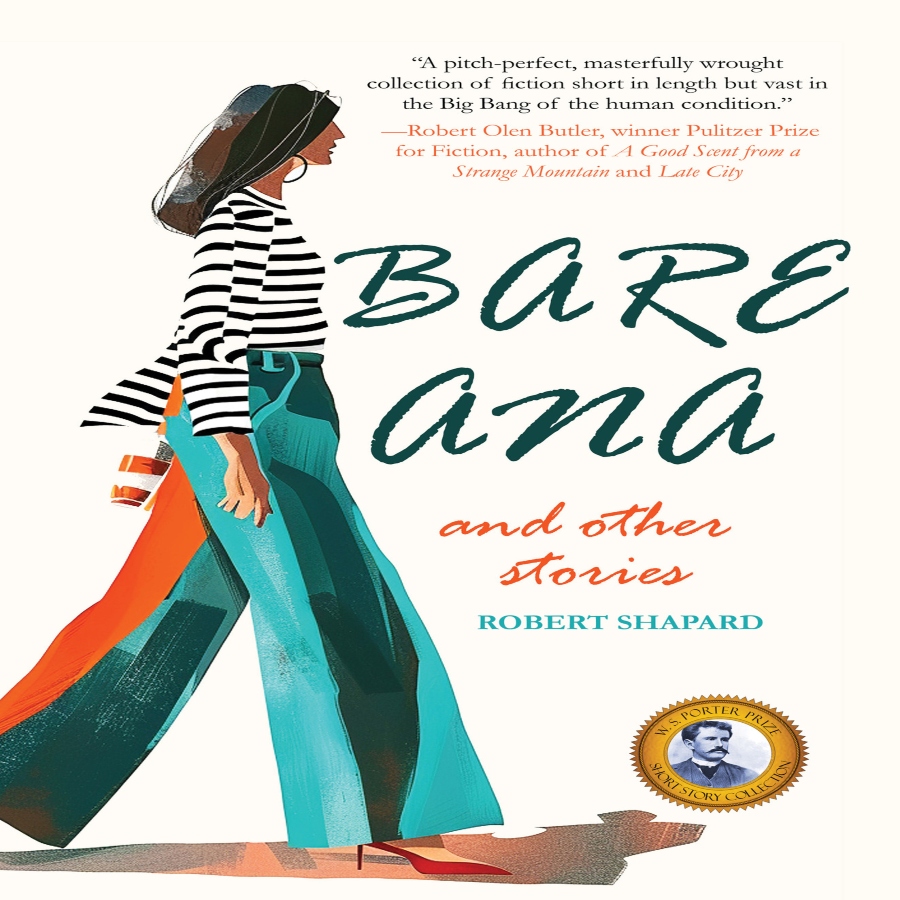

Robert Shapard’s collection, Bare Ana and Other Stories, will be released by Regal House Publishing in February. Winner of the 2022 W.S. Porter Prize, this full-length collection brings to life an array of flash and short-short stories that are by turns delightful and heartrending.

Readers might have high expectations of a book by such a renowned trailblazer in the flash form; Shapard’s career includes co-creating and co-editing the iconic anthology, Sudden Fiction: American Short-Short Stories, in 1986, continuing through W. W. Norton’s long-lived and long-loved flash anthology series, including Flash Fiction International: Very Short Stories from Around the World.

I believe readers will not be disappointed in Bare Ana. Each story is masterfully crafted with an eye to character and circumstance. Shapard’s expertise and unique voice are on full display here. Nothing is predictable in these pages; the settings are vivid in ways you might not expect, and the characters face choices that will make your pulse race. I predict these stories will haunt you long after you’ve closed the book.

—Myna Chang

***

Myna Chang: First, tell us about Bare Ana and Other Stories. Did you have a particular goal in putting the collection together? Were you hoping to share a specific theme or mood with your readers?

Robert Shapard: I asked myself those same questions. A friend suggested a working title, “Water Issues and Other Safety Concerns,” like I was compiling a manual. It was tongue in cheek, though I did have a character walk on water in one of my stories. Another sank in a warm bathtub full of goldfish. But the stories are serious, even if a few have comedic elements. Anyway the working title is too long. Have you noticed how giant those block letters are on book covers now? And where would the bookstore clerks shelve a book with a name like a manual, in the “Self Help” section? I was re-discovering my own stories as I gathered them. Most are recent, but a few go way back. What I found, more than anything, was I loved the people in them. To me any could be the title character for a collection. Ana was the only one who lived in the future. In that way, she sort of stood above them all. And, if you put “other stories” in little letters, her name fit on the cover.

MC: I’d love to focus on your title story, “Bare Ana” (Juked, 2005). As a speculative fiction fan, I was struck by your compelling world-building. With a few quick strokes, you establish a distinct backdrop of social and cultural expectations, while keeping the reader grounded in the familiar. I’m curious about your approach to creating such a rich and complex stage without allowing it to overshadow your characters. How do you achieve the right balance?

Robert: I admire world-builder writers like Chris McKinney, who publishes with Soho Press. In his latest novel he has all humanity living under massive pressure at the bottom of Earth’s oceans. But “Bare Ana” is just a very short story, with hardly any room to construct a future world. So I had Ana’s young husband do it. He has advantages—his listeners are in the future, too, so he doesn’t have to explain the technology. When he refers to a “stem,” they already know what it is. We readers in the past have to put two and two together, but it doesn’t take long. The stem is in the middle of the parlor, and the tattoo lady goes right to it, so we know it’s important. Soon holograms are shooting up from it into the air along with commercials. That’s pretty much all we need to know about stems and a lot about this future society.

When he speaks of a “blooming” in the skin he’s reminding his listeners how excited they got when they were kids. It also puts us past readers in suspense with how blooming can go wrong. Other things like pre-natal teeth straightening simply function as examples without needing elaboration. And the reactions of the characters themselves can tell us a lot, like at the end when the nurse and doctor are both congratulatory and bored with the monstrous infant at birth.

There’s an anecdote for this that’s perfect. It’s the one about Gertrude Stein calling Ezra Pound a “village explainer.” She meant a particular kind of village idiot who is compelled to constantly explain things to people that they already know. I didn’t want Ana’s husband to be a village explainer.

MC: Stories with a strong sense of place stick with me. “Motel” is such a story—the dark road, the cinder-block motel, the utter isolation. And the dust! Can you talk about your inspiration for this piece? In addition, I wonder which came first for you: the characters or the location?

Robert: Location. It also came with a ready-made event. At 17, I was in a car with friends and crashed into just such a motel. It was on just such a night in just such a tiny town near the border of West Texas, South Texas, and Mexico. No one was hurt. Later, we did get thrown into a Mexican jail. But we’re not in “Motel” at all. The people in the story are completely made up. Where they came from is a mystery to me, and I care for them more than anything that actually happened to me.

MC: I think the cars of our youth often hold an almost mythical place in our memories. In your collection, several of your characters drive a Buick. Does this hold a special significance for you? Does it represent a certain time or place or mood?

Robert: I grew up in my grandparents’ house. My grandfather was a civil engineer who owned a company that built streets. It was a tough business, always competing for the lowest bid, and he drove the cheapest possible company car. But my grandmother—who was wise, loving, smoked, drank, gambled, and was the first woman driver in her small Texas city— had a pink Buick. It was the luxury model that had four, not just three, fake portholes on each side, like some weird rocket ship out of the Jetsons. It lacked the usual luxury whitewall tires, but my grandfather insisted the cheaper blackwalls functioned just as well. The power steering made for effortless driving except for hard, tight turns in parking lots, when its hydraulics made high-pitched squabbling sounds like an alarmed turkey. I loved that car. It must be buried in my subconscious because it has now supplied me with Buicks for three different stories. To be fair to my subconscious, I’d like to note that it has also supplied cheaper cars in other stories, including a 1947 Ford coupe and a 1978 Ford Pinto.

MC: Throughout the collection, I noted an embrace of white space and an ending note of ambiguity, inviting me in and allowing me the freedom to interact with the characters and settings in my own way. I love that! Do you consciously create this accessibility for the reader? Does it arise organically as you write, or is this something you layer in (or extract) in your editing process?

Robert: I like to think my stories end when no more needs to be said. It’s true they don’t all end with the snap of a lid. It makes me think of Grace Paley’s story “Mother,” which opens with her saying she always wanted to write a story about her mother and end it with the line “And then she died.” Yet we’re surprised somehow, when she does end with that. How did she do that? It took me years to realize that Paley could probably write for the rest of her life about her mother. So she came up with an anti-non-ending, and nailed it.

My story “The Dummy” caused a debate among the editors who nonetheless published it. One side insisted the story didn’t properly end. The other side said no, it was a challenge. A questioning of what a story is. To me the challenge wasn’t whether it was an ending or non-ending but just finding one. When the narrator discovered the body, he could have just said, “It was my father. He was dead. The End,” like Grace Paley’s story. But re-reading the story now, I see the father wasn’t real, in so many ways. I suspect as an actor he was just pretending to be the sixth-grade football coach. He even came to the dinner table dressed in various acting roles, pretending to be someone else, like King Lear or the Sheriff of Nottingham. Clearly, the narrator doesn’t want to lose him. The father’s like a movie the kid doesn’t want to end. Now, I’m seeing so many elements I didn’t know how to explain at the time. Yes, clearly the end is a call for reader participation. But what about the boy? He ran away from home in high school and had to be dragged home again. Did he have mental issues? Is he having one now? Is he the one who doesn’t know how to end? In one last look at the father, I see the one true thing about him now, whether he’s real or, as the story says, made of crumpled paper. He always loved the boy and his mother.

Another “white space” story that is easier to untangle is “Turtle Creek.” I tried longer versions with different endings. I followed the mystery of the couple missing from the wreck (never solved), I traced the lives of the youths at the party, who mostly didn’t come to anything. Were they a wrecked generation? It felt good, like whacking weeds, cutting those endings. I kept the shorter version, the one now in the book, trying it on everyday readers like trainers at the gym and acquaintances at the coffee shop. At the non-ending, all of them, independently, flared their eyes for a second. Then they all said the same thing: “That was my high school!” I’m not sure what this means, but it’s been audience-tested. I consider it an ending.

MC: Is there a specific story that embodies the heart of the collection? Which story is your personal favorite?

Robert: It’s hard to pick favorites, but I especially enjoyed writing the ones invented out of whole cloth, that seemed to come out of nowhere, like “Lobster,” “Best Boy,” and “Bare Ana.” You could argue any story, no matter how purely invented, is partly woven out of bits of memory. But these seemed to be less weighed down by memory than to unfurl on the breeze of an idea. Most of my stories unfurl, so maybe together they’re the heart of the collection. But the first story and last story have special meanings for me, as a writer. I was a long story writer until the first story, “Thomas and Charlie,” showed me I could write flash fiction, and others followed. The last, “Julie Elmore,” won a prize as a very long story (under a different title) so I wasn’t inclined to change it. Then, a friend challenged me to turn it into a very short story. I did, wondering, If the three quarters I cut wasn’t necessary, how could it have won a prize? But now it’s a better story.

MC: You’ve anthologized short-shorts from some of the best-known authors in the world. Is there a dominant quality or element that initially drew you to those stories/authors? Are you still drawn to those aspects of story, or has that changed over the course of your career? Are there any favorite pieces that you go back to again and again?

Robert: When we started we were looking to help establish a new form of very short fiction that didn’t have a name. The literary establishment of the day considered them odd, unfinished pieces of longer, legitimate fiction. Often, if they spoke of them at all, it was to mock them. We liked them whatever their quality—funny, moving, powerful, charming, experimental—often with the reach and depth of a traditional story, just in a tiny space. That left your “dominant quality or element” in collecting them simple. They had to be short enough, and they had to be great, to quell those mocking critics. To focus on the story, we blacked out the names of authors on batches we sent around to readers, helping us rate them. Later, when we had to match the stories with author names, we weren’t surprised that some were well-known. More surprising was how many were not. Not everyone could write a great story, but a great story could be written by anyone. We always held to that. Yes, there were adjustments, such as for the international anthologies, where we relied on translators, some of them responding to the demand for work by well-known foreign authors. But they translated lesser-knowns, too, and the translators themselves were often lesser-known, and their work was brilliant. They added to the form, which by then had various names—flash fiction, sudden fiction, micro fiction.

You asked for favorite pieces. There are so many. Here are just a few:

In Flash Fiction Forward, Hannah Voskuil’s “Currents” is a story in reverse that we care about as it moves ever back in time. In Flash Fiction International, H.J. Shepard’s “Please Hold Me the Forgotten Way” and Edmundo Paz Soldán’s “Barnes” are perfect examples of an American flash versus a Latin American micro. In the “Theory” section, Katharine Coles’s is my go-to mini-essay on the difference between flash fiction and prose poem. I never tire of Jayne Anne Phillips on writing good one-page fictions (pair it with her essay, “Cheers,” in The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Fiction). Finally, in Sudden Fiction, John Cheever’s “Reunion” is perfect for a single class in characterization. But so is Sara Freligh’s “Reunion” (with the epigraph, “After John Cheever”), which I read recently in her book A Brief Natural History of Women. Cheever’s is brilliant, a two-dimensional snapshot; Freligh’s is equally brilliant and three-dimensional.

MC: Do you see any upcoming challenges (or opportunities!) facing flash writers/editors? Do you have any hopes or predictions for the field?

Robert: Since I go back a ways with flash I tend to look at the big picture. Not that long ago, translators Aili Mu and Julie Chiu were telling us flash had become highly popular in China because flashes are “device independent and compatible with today’s technology” and “offer relative freedom from censorship not enjoyed in other media.” Oppressive regimes in the Middle East and elsewhere have been known to censor not only news but fiction, and others may in the future. But flash isn’t just a reaction to politics. A young scholar from India, Dr. Ruchi Nagpal, came to Austin just this fall to explore the Harry Ransom Center’s Flash Fiction archive (it’s the world’s second, the world’s first is at the University of Chester’s Seaborne Library). She says, “Everyone in India has a smartphone and tablet,” and micros are everywhere. She’s also into flash theory, wants to anthologize flash fictions from other Asian countries, like Singapore, and is interested in long-thriving Spanish language forms like the microcuento. And now the rest of the world … but wait, let’s stop here, because if we add the United States and other English-speaking countries, we’ve already got more than half the world’s population.

That’s a long way from a time—not that long ago—when establishment critics were dismissing flash as hardly worth reading. So with its tremendous growth, has flash now become a true sub-genre of fiction, like the novel, novella, and short story? Does it matter? I see flash as still changing, exploring. Haven’t the novel and poetry changed over time as well?

As for new challenges and opportunities, I judge by what I see in bio notes these days. More writers are describing themselves as flash fiction writers, often in combination, such as “novelist, poet, and flash writer.” That tells me they’re expanding their vision and skills as a writer.

MC: What are you working on now? What’s next for you?

Robert: I write stories whenever they come to me. But today I’ve been sending around early copies of Bare Ana and Other Stories, hoping people will review it. (My publisher, Regal House, a wonderful, small, traditional press, does that too.) Last night a revision for my novel-in-progress woke me and I scribbled a note which I discovered this morning: “What if J never went to college? It changes everything.” Over coffee, I thought, “Was the J for Julie? or Jonathan?” If I remember, who knows where it will take me.

***

ROBERT SHAPARD’s stories have appeared in magazines such as New England Review, Necessary Fiction, New World Writing, 100 Word Story, The Literary Review, Juked, Bending Genres, New Flash Fiction Review, Fractured Lit, Kenyon Review, and Typishly. He and his wife live in Austin, Texas.

Find Robert:

MYNA CHANG is the author of The Potential of Radio and Rain. Her writing has been selected for W.W. Norton’s Flash Fiction America, Best Small Fictions, and Best Microfiction. She has won the Lascaux Prize in Creative Nonfiction and the New Millennium Award in Flash Fiction, and her poetry has received a Rhysling Award honorable mention. Find her at MynaChang.com and on Bluesky at @MynaChang.