I ran over a nightjar with my car. It wasn’t my fault—it sat there roosting in the right lane of the road. I was on the phone with my brother when it happened; he’s apprenticing in ear-nose-throat. He’d changed rotations, went straight there from gyno. They’re all mysterious cavities, you know?

I thought of swim days, when my parents would go on a date to the local pool. I’d stay home alone, stand in the foyer mirror with my head between my legs and try to see inside myself. I’d just watched Mean Girls, wanted to know if I had a wide-set-vagina-and-a-heavy-flow like the girl in the movie.

It’s like when a woman brags at the table while ordering lunch, I’ve got such a small stomach. I can’t eat much. How does she know?

I’ve got the nightjar in the backseat, wrapped half-dead in a coat. It’s my boyfriend’s wool hoodie, the one that cloaks the back of the chair every night when he comes home from work. I felt so restless, staring at its volume, I tossed it in the truck.

I began Googling nightjars, how they’re called goatsuckers cause they’re storied for sucking the milk from goats. I think that through from both ends, from the vantage point of a worn goat’s nipple, and from the short beak of the bird. All that giving-and-receiving. I think about the gas station I never reached, how I was in the process of turning right when I hit the bird, to fill up. You can watch the price go up and up; imagine the gas pumping in, but you never see inside the tank.

I had a dream last week that I pulled a salamander from myself like its tail was a tampon string. Are other people like this? I ask my brother. I’m always thinking about my insides, what I can’t see.

He tells me he’s glad to be out of neurology, a brain laid on the table, portioned out like cheese. Sometimes it’s best that we don’t see, he said. The organ donor was a woman who bent down to pick up the newspaper, sneezed, and had a fatal stroke.

I think of my friend Lucy, the way she looked at me when I’d told her I’d cheated last year—the way she grew quiet. I watched her chest rise, her lungs filling with what she would not say.

I dreamt of a balloon that night, popped inside of me, the puckered rubber knot hanging down. My subconscious always brings me back to the womb—all the ways I could be broken.

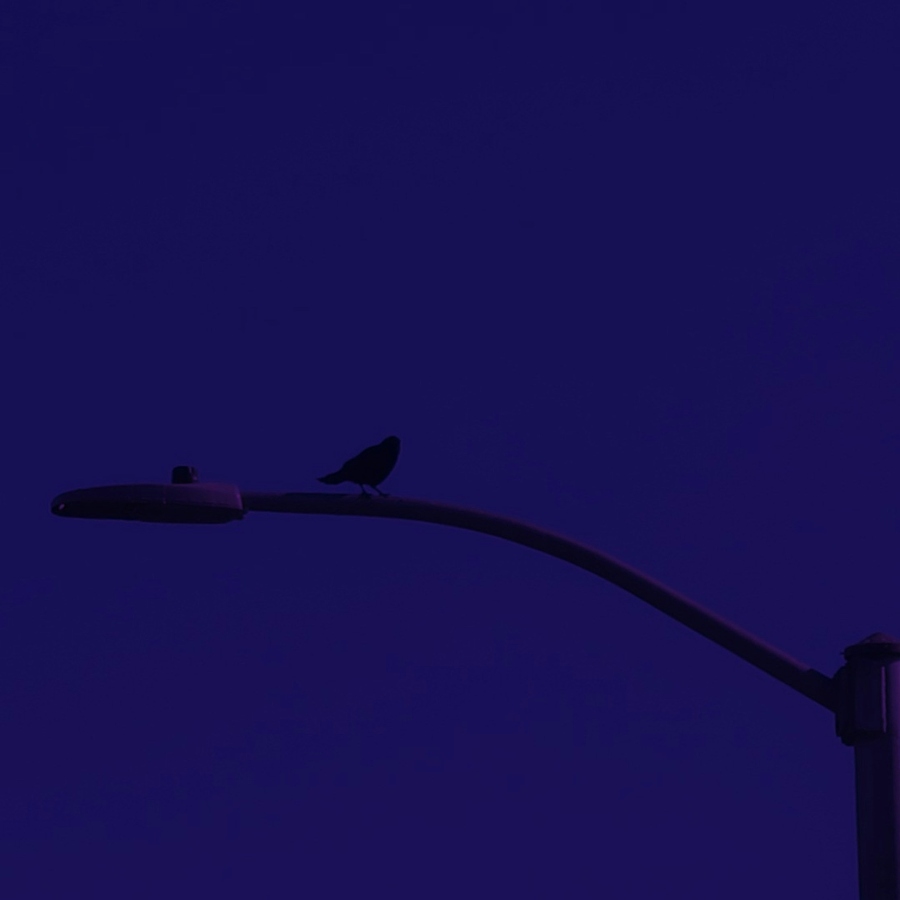

I’m startled by a honking car, get the motherly instinct to check the backseat. The nightjar is legs-up, as dead as it can be.