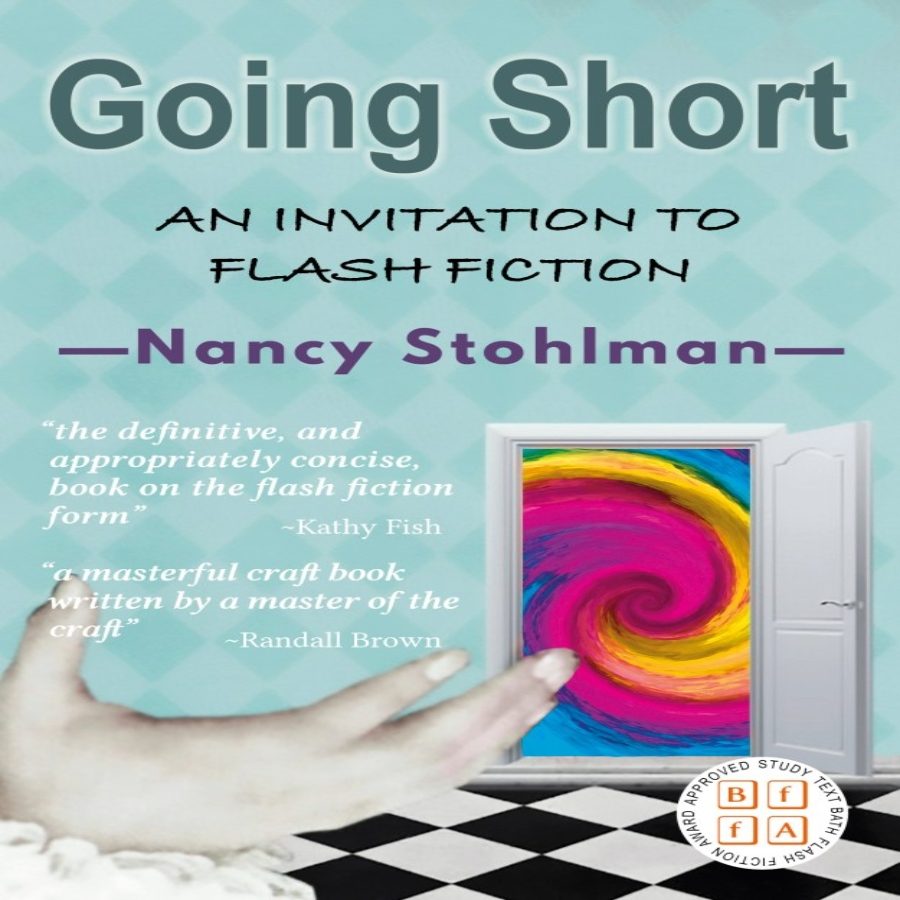

Going Short: An Invitation to Flash Fiction (An Excerpt)

Flash Myth #1: Smaller Is Easier

Let’s debunk Myth #1.

Housed in the Chicago Institute of Art are the Thorne Miniature Rooms, tiny replicas of actual historic rooms painstakingly crafted on a scale of one inch: one foot. You press your face up to each of the 68 windows and gaze at the fully formed world inside— complete with exotic woods, fabrics, chandeliers and intricate, hand-woven rugs. The attention to detail in each room would be impressive even at life size, but the true fascination is the fact that they are just so damn tiny!

One of the reasons people love flash fiction is because, like the Thorne Rooms, there is something awe-inspiring about entering a perfectly formed tiny world. When done correctly, tiny is part of the art: the Mona Lisa on a grain of rice, a sculpture of Charlie Chaplin balanced on an eyelash. And it often requires more skill from the writer, not the other way around. Creating something tiny takes a different level of expertise and precision.

Sometimes when people discover flash fiction they assume: oh, it’s cute, it’s small, it’s easy. But to fully appreciate flash we must assume mastery: the story is small because the author has decided to tell it this way.

Flash Myth #2: Readers Have Short Attention Spans

This is probably the most common flash myth. But readers aren’t enamored with flash fiction because they have short attention spans—that’s like saying the sculptor of the bonsai tree didn’t have the attention for a full-grown tree, or that people who eat sliders don’t have the attention for a quarter-pound hamburger. Maybe, just maybe, they like sliders and bonsai trees?

In the same way, readers love flash fiction because it’s complex and breathtaking and accomplishes so much in such a tiny space.

In fact, flash fiction requires a more sophisticated reader. The story demands the reader to “pay close attention”—every sentence, every word takes on a new significance, if only for the limited number of them. The reader must jump the gaps, fill in the blanks, follow the breadcrumbs, and inhabit the purposeful spaces left by the writer. Which means that flash fiction is cultivating a new symbiosis between writer and readers, on and off the page.

As readers, we’ve gotten used to sitting in the audience and being entertained. But it’s nearly impossible to passively consume flash fiction. Leaving things unsaid and undigested requires effort and interpretation; the reader steps out of the role of voyeur and becomes an active participant in the story. It’s this act of interpretation that keeps art vital—no longer just watching from a darkened audience, flash fiction invites the reader up on the stage, hands them a tambourine, and tells them to keep up.

Flash Myth #3: Bigger Is Better

“Important” literary works are big. Therefore, some people still dismiss flash fiction as trivial. How could anything important be accomplished in such a small space? Flash fiction is good for barroom bets, not for serious literature.

The implication here is the more we have of something, the better it is. War and Peace is “important”: it’s long, it’s hard, it’s complex, it’s 1,200 pages. But Old Man and the Sea is only 120 pages and won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Should we assume that Tolstoy worked 10x harder than Hemingway or that his work is 10x more important?

The truth is they can’t really be compared. Flash fiction should be judged on its own terms. It’s meant to be digested in one sitting—it encourages speed, not languishing. Longer literature is meant to be enjoyed over time. But flash fiction doesn’t look for sweeping vistas. Flash fiction is not the epic saga. Flash fiction is that guy on the beach with the metal detector. We don’t need to know his history, we don’t need to know what he looks like. Just tell us what he finds.

Nancy Stohlman has been a writer, editor, publisher, and professor for more than a decade. She’s published multiple books of flash fiction and flash novels including The Vixen Scream and Other Bible Stories and Madam Velvet’s Cabaret of Oddities, a finalist for a 2019 Colorado Book Award. Her work has been anthologized widely, appearing in the W.W. Norton New Micro: Exceptionally Short Fiction, Macmillan’s The Practice of Fiction, and The Best Small Fictions 2019, as well as adapted for the stage. She teaches at the University of Colorado Boulder

Submit Your Stories

Always free. Always open. Professional rates.