I think I found John Fulton’s short story collections somewhere in my early writing days; after reading stories by Carver, Baxter, Bausch, Jean Thompson, and Tobias Wolff. I’ve always found a warmth and a beating heart in John’s stories, a way of seeing the world in both the light and the dark, with a punch of language and a care for his characters that might have been missing in those earlier stories that made me want to be a writer. In The Flounder, Fulton has found a deeper reservoir, a confidence in his characters to reveal themselves, a confidence in his sentences and structures to affect the reader, to make a fountain of resonance I plan on returning to soon.

Tommy Dean: So many of these stories have great opening lines full of conflict and intrigue. Do you have the first line when you start a story, or do you create them during the revision process? Do you consciously try to load your stories with conflict in the openings?

John Fulton: Great question and observation! The opening lines are extremely important to me for two reasons. First, they help give clarity and direction in the vast forest of ideas, characters, and images that tend to arrive indeterminately at the beginning of the writing process. The first lines provide a trail of breadcrumbs, so to speak, that I can look back on for an idea of where the story might go next. Before I get that crucial first paragraph, I’m often lost. But the opening may not come until I’ve made a mess, written many aimless paragraphs or pages and wandered through the accumulating material. But in the wanderings, I can stumble upon a sentence or two that begins to suggest the stakes and focus of the story or, simply, what it’s about.

That’s where “conflict and intrigue” can be crucial because they tell me both what the story is about and why it matters. The beginning of the third story in the collection, “Box of Watches,” is one example of how important a clear statement of conflict and stakes are when I begin:

That Friday afternoon in AAA Guns and Jewels, Shaun’s life flashed before his eyes, just as they said it would when you faced death, though it wasn’t his death but his grandfather’s that made the events of Shaun’s 22 years begin to reoccur as soon as he heard the old man shout, “Go right ahead and shoot me, you little shit!”

As soon as I arrived at these lines about a grandfather and his grandson, Shaun, I knew a great deal about the story that would help me write it. Of course, this is a hold-up story, and I knew that there would be a gun in it and where the action would take place (in a pawnshop), before I arrived at these lines. But that phrase about “Shaun’s 22 years” suggested that this character’s entire life with his grandfather would be in play, that a kind of chronicle of that life would unfold during the robbery, and that one of the challenges for me as a writer would be the tightrope act of balancing present action (the hold-up in the pawnshop) with past action (the scope of Shaun’s life with his grandfather up to this moment).

Secondly, the initial lines of a story are crucial to me because they make an assertion about how language will work (diction, syntax, sentence length, the quality and tone of images, etc.) in the story. This is not about content or event or stakes so much as it is about sound, rhythm, and cadence. For example, the cadence and pace of that first sentence above suggest the menace of the gun before we see it. The first sentence is long, full of momentum and kinetic energy as are most of the sentences that follow. There’s violence in the language, and that works in tandem with the story. I often tell my students to “follow the language to the story,” by which I mean to be sensitive to the sound the words make and allow them to lead you organically to what comes next.

TD: Most of your stories eschew the use of quotation marks. Did you have a purpose for leaving them out? What does it add or take away from the reading experience?

JF: I often don’t find quotation marks necessary because good dialogue sets itself off as speech immediately. Its rhythms, tone, and diction distinguish it from the rest of the language of the story. I think fewer symbols or marks on the page can make for a less mediated reading experience. Signs and guideposts that tell you how to read necessarily take up some mental space. Without those little curled lines, you can simply read and hear the speech rather than have it dictated to you as such. Of course, the writer has to get the dialogue right. If there’s real confusion about whether a line is dialogue or not, that is likely the writer’s fault.

TD: Your stories are often populated by characters who refuse the conventional for their lives. Are stories made interesting by or through characters that refuse to follow the “rules” of society?

JF: Thanks for that observation about my work, Tommy. I wouldn’t have said this about these stories. But now that you bring it up, I see that you’re right. My characters do cross lines, though many of them live inside communities that have rigid lines, which makes the crossing of them impossible and/or irresistible.

This may have something to do with the fact that I was brought up by a single mom in the 70s and 80s as a fundamentalist Christian. There’s not a lot of wiggle room in this community, and those in it are often motivated (and manipulated) by powerful emotions—shame, guilt, fear—to stay on the straight and narrow. My family lived in the rural Western U.S. (Montana, Utah, desolate parts of California), where this religion and others like it (mostly Mormonism) were very common. I don’t recall meeting an atheist, or anyone who would call themselves “secular,” until I was a teenager and living in a real city (Salt Lake City). I eventually escaped that world, but it took a few decades and some years living at a great distance from home. I spent about five years in Europe in my early and mid-twenties.

In The Flounder, I write about this experience (both living inside rigid faith communities and escaping them) more than in any of my previous books. Until recently, I found it hard to represent this world. I tend to need decades of perspective on autobiographical material before it works its way into my fiction.

Characters who break the rules are interesting because we can’t pin them in or anticipate their next move. The first story in my collection, “Saved,” begins by highlighting just such a character: “It was true what Mrs. Berry said: No one expected to see an old woman in a muscle car, a convertible Mustang with polished chrome bumpers, a hood scoop, and an engine that ran with a throaty hum that we could feel in that soft place just below our stomachs as she pulled alongside us one day on our walk home from school.” The opening announces that this old woman isn’t who the two pre-adolescent kids at the center of the story expect her to be. She loves fast cars and challenges the fundamentalist views of these two kids, who live in fear of being left behind when the Rapture takes place. While Mrs. Berry and the kids befriend each other, the challenge she poses to their beliefs eventually causes havoc. Faith is powerful and losing it is painful. But the old woman also frees them—or begins to free them—from some very constricting ways of seeing the world and themselves.

TD: I loved your use of the second-person point of view in your story “Stitches.” I wonder if this point of view is best at exploring certain power dynamics between the main character and the antagonist? I expected the main character to be a younger boy, so I’m wondering if you were playing against my expectations? Why don’t we see this point of view used as much with older narrators?

JF: The second-person point of view is mysterious. I don’t entirely understand why it works in certain stories and, at least for me, doesn’t work in others. At its core is a contradiction or dissonance, especially when the “you” is an individuated character. In “Stitches,” the second person pulls the reader in with a seemingly generic address (the “you” could be the reader or a kind of “every person”) even as we learn that the “you” in this story is a middle-aged professor of English on a hunting trip with his elderly and somewhat estranged father.

This inherent dissonance or intimate distance in the “you” was instrumental for me when writing the story because it’s probably the most autobiographical piece of fiction I’ve written. Like the “you,” I am a middle-aged English professor. I have two kids. I didn’t know my father very well when I was a youngster and now see him a few times a year on hunting trips when we talk about a limited number of subjects: football, construction projects, the weather, and, more rarely, why he chose to leave our family before I was old enough to remember him. (Note that a lot of other things in the story are made up.) That’s charged material, and the second person point of view created, I think, a lens through which I could look at and inhabit these characters both from the inside and from an almost clinical remove so that the sentiment in the story would be at once felt and carefully observed. It’s not, I hope, merely personal. By the way, this wasn’t an intellectual decision I made while writing the story. I tried the second person and it worked or, at least, allowed me to enter and engage with the material in a way that first or third person didn’t.

Your observation—that the second person is often used for younger characters and not older—is interesting. I think you’re right, though I’m not sure why that is. There are a lot of coming-of-age stories that utilize it: Junot Diaz’s “How to Date a Browngirl, Blackgirl, Whitegirl, or Halfie,” Loorie Moore’s “How to Become a Writer,” and Peter Ho Davies’ “How to Be an Expatriate.” Perhaps this is because all these younger narrators are experiencing the disorientation of becoming an adult and colliding with the structures in society (sexism, racism, nationalism) that don’t recognize individuals. The dissonance in the “you” captures the confusion of that—of being or becoming one thing while being seen as another. These are also all how-to stories, which has become a genre of the second-person story since the you is a stand-in for an assumed audience that wants to learn something. “Stitches” doesn’t belong to this genre. Instead, it’s a story about family trauma and it may have, at least in part, been suggested by a second-person novel that is also, at its core, about trauma: THE DIVER’S CLOTHES LIE EMPTY by Vendela Vida. I’d highly recommend this book. For obvious reasons, the second person, with its tension between distance and intimacy, can be expressive of trauma.

TD: One of my favorite stories in the collection is “What Kent Boyd Had.” How did you discover/find this character on the page? Did the point of view come to you in the very beginning? It has a masterful use of omniscient narration, but I never felt too far away from this main character! How do you often go about creating your characters on the page?

JF: I’m glad you liked that story. It was a lot of fun to write. It’s what I call a “list story,” which is what it sounds like: a story told in the form of a list of things that the rapacious and loud Kent Boyd accumulates over a lifetime. The story came from years of teaching and thinking about Tim O’Brien’s classic short story “The Things They Carried,” also a list story that brilliantly gives expression to the experience and trauma of the Vietnam War for a platoon of soldiers. O’Brien uses long lists of the sort of equipment these soldiers carry through the jungle. With these lists, he characterizes them, creates tension, and structures the story. Using this form to tell a good story is tricky because lists aren’t inherently dramatic. They’re simple storage devices for data that help us remember what to get at the supermarket or for Christmas gifts, etc. The challenge, then, is how to create tension and human drama with this simple form, which I could talk about all day.

But the more important question is, why use a list at all. For this story, it had to do with the character of Kent Boyd, who is “self-made” and the kind of man who is out of fashion these days. He’s a close cousin to John Updike’s Harry (Rabbit) Angstrom in the Rabbit novels and perhaps Philip Roth’s Nathan Zuckerman. He’s also an amalgam of a few of my uncles. These guys aren’t necessarily pleasant, though they know how to have a good time. They have outdated ideas about their own privilege, not much self-knowledge, and tend to see the world as a place that belongs to them. Their egos are large in inverse proportion to their vulnerabilities and deep-seated and often unacknowledged needs. The list becomes important and expressive of Kent Boyd because he grew up with little save for his backwards Christian faith, which he loses as a teenager. He goes from Pueblo, Colorado (if you’ve ever been there, you know it’s not a place you’d want to stay) to Berkley and finally to Boston, where he becomes a successful and wealthy patent attorney. Given his childhood, it’s not surprising that he sees life as a process of acquisition and starts accumulating people, accomplishments, and things: a wife, kids, a few big houses, fancy cars. But the story undermines him by including things that don’t fit with his ideas of success such as alcoholism, affairs that end badly, erectile disfunction, heart disease, a bottomless need for approval and love, a terrible fear of death, an angry adult son, etc. These are the items that express complications and contradictions that are necessarily human and that, I hope, create the tension that fuels the story and that gives this character depth and interest.

TD: What does your perfect writing day look like? How often does this happen?

JF: My ideal writing day would be 4-8 hours at the desk, with no distractions or other obligations, when I’m absolutely in the zone and focused on a project in progress that has me so excited and expectant that I can think of nothing else but what’s happening on the page. I have two kids, which means there are usually other obligations, places to be or go. I’m also a professor and I direct the MFA Program at the University of Massachusetts Boston. I really enjoy my students, my colleagues, and the program. But all this requires attention and time, which often means no writing on some days and no more than a couple of hours on other days. Being in the zone feels mostly like luck. However, it has very little to do with luck. I usually get there only by being lost and frustrated for many hours and days and sometimes months at a time. I need to produce material—pages and pages—to find the story.

As for the second part of your question, I’d say that I experience no more than a month (sometimes two) every year of ideal writing time. Typically, this would be in the summer when I’m not teaching. That said, I try to make it to the desk at least five days a week, and I’ve gotten a lot of work done on less-than-ideal days. Alas, that’s life: almost always less than ideal.

TD: As a writer of several short story collections, how do you find the unexpected in your new stories? How do you keep yourself from repeating plots or themes?

JF: I love this question in part because I don’t entirely know the answer. I can tell you, however, that once I start to repeat myself, the work suffers and feels stale, old, enervated, all signs that I’m too much in control and know too much about what’s going to happen on the page before it happens. If my work isn’t surprising and unpredictable to me, it won’t be those things for my reader.

That said, I think writers tend to find material in what obsesses and bothers them. And writers gravitate around the same issues until they’ve exhausted them. Obsessions are good and I follow them. To be more specific, an obsession can be ideas or clusters of images or situations or an experience that shadows me like a dream I’ve just woken from and can’t quite articulate or fully describe. It often takes years for me to find the form or language that will allow an obsession to become a story. Messing around, improvising and experimentation can do the trick. For example, trying the second person point of view gave rise to “Stitches,” while using the form of the list made “What Kent Boyd Had” possible. I’d been trying to write the title story of my new collection for decades, but I wasn’t able to finish a draft until I structured this tale of infidelity around a Grimms’ fairy tale, typically called “The Fisherman and His Wife,” though it’s also sometimes called “The Flounder.” Once I’d introduced the strange magic of this fable into the texture and language of the story, I was able to write it.

I think a large part of keeping the work fresh and new involves following our instincts. While part of writing is about discipline, craft, keeping the language sharp, much of it is about dreaming, following hunches, not overthinking the next step. Finally, of course, we have to be out in the world, live, take chances in our lives, and broaden our experience.

TD: How has publishing changed from the beginning of your career to this book? Any advice to writers of story collections?

JF: I’m not an expert on publishing, but the big houses have undergone more consolidation and corporatization, which means more pressure for profits. The bestseller has become, I think, the focus, whereas a decade or two ago, a number of books that sold modestly could serve a publisher well. Midlist authors—those who aren’t bestsellers—generally have a harder time right now. My first two books, a story collection and a novel, were taken by Picador. But when my agent submitted my third book, another story collection, Picador wasn’t interested. They wanted a novel or nothing.

The good news is that there are more independent and university presses than ever. It’s still tough for story collections and a lot of these presses don’t make it. The wonderful imprint (Yellow Shoe Fiction at LSU Press) that published my second collection of stories went under when Covid led to budget cuts at LSU. I just wrote a piece on the form of the novella, which will appear this month on LIT HUB. I love long stories. Many of the entries in THE FLOUNDER come to about 10,000 words. I’ve published four novellas, which I define as stories of about 15,000-50,000 words. For the piece in LIT HUB, I read a pile of wonderful novellas, an experience that gave me faith in the culture of literary publishing in this country. The novella has mostly been ignored by big houses, with some exceptions. But independent presses (Black Sparrow Press, Akashic Books, Dorothy, Seven Stories Press, and many more) have championed the form. You’ll have to search for them, but the novella is alive and well.

As for my advice to fellow writers of story collections: Make sure your work is the best that it can be. Then persist in looking for a press that believes in the book.

TD: Do you have an interior monologue? How does this inform your writing?

JF: I have “interior monologues” and some of them aren’t great. At times, I find myself reading popular books with an envious eye. That’s unhealthy. My constructive interior monologue is simple: Follow your gut. Read good stuff from a range of literary traditions and with an eye towards the limitless possibilities of language, form, and structure. Go to the desk with the ambition of writing that story or novel that’s been bothering you for weeks, months, years. And persist! If you’ve done the reading, follow your gut, and keep at it, you’ll eventually get the work done to the best of your ability.

TD: Tell me about a book or story that helped start your writing journey.

JF: I’m in my fifties now, and when I started writing back in my early twenties, Raymond Carver was very popular in classrooms. I read an anthology of his essays, fiction, and poetry called FIRES that really moved me mostly because (and I don’t always think this is the best reason to be moved or influenced by a book) I could identify with him and the work. In the essays, he talked about coming from a working-class family and being a janitor while writing his first stories. I came from a similar background (my mother’s dream for me was to join the military), and Carver’s simple language showed me that stories could be told in a language free of pretention, fancy words, and whatever it was that I then associated with literature. Carver’s work has a deep authenticity to it. You sense that he’s writing what he knows and that that’s more than enough to give life and interest to the work. That was a revelation to me at the time. Later, I discovered work (Nabokov, Rilke, Munroe, Atwood, Kafka, Morrison, Baldwin, Kundera, Calvino) that was much less familiar and that showed me a wide range of possibilities. But Carver’s quiet brilliance spoke to me and made me feel that I could also be a writer.

TD: Can writing be taught? If so, what are the elements a writer must learn?

JF: Writing can be—and should be—taught. I’ve always been surprised by those who say it can’t be. And yet I graduated from a college in the 1990s that begrudgingly offered only one creative writing course because the English faculty at the time felt that poets and fiction writers were born and couldn’t be “taught” to write. I’ve been teaching fiction writing for almost twenty-five years, and I’ve watched students blossom in one or a few semesters in my classes. Many of my students are now incredibly accomplished writers. One of them just sold her third novel to HBO and, I’ve heard, has quit her day job for good. At the same time, I don’t believe you can teach somebody to be the next Joyce Carol Oats or Alice Munroe or Toni Morrison. Some individuals are obviously more talented, driven, and determined than others. You can teach craft: dialogue, detail, exposition, conflict, narrative modes, point of view, etc. Writers need to learn and metabolize these skills until they are second nature. I also try to teach students how to read as writers, and I give them as much exposure to a wide variety of authors and literary traditions as possible in a semester. I can’t tell students which literary traditions they should work in or how they should write. But I can show them a vast array of possibilities and let them loose to find their authors and their voice(s). Writers learn way more from reading work that excites them than they’ll ever learn in a classroom.

Otherwise, the writing classroom can (and I hope mine does) offer writers community: a group of like-minded peers who exchange work, offer support, and suggest great books and authors to each other. The writing life can be grueling and unforgiving, which makes community essential.

TD: What are you working on now?

JF: I usually work on several projects at once, taking this or that piece out of the shelf, revising it until I hit a wall or finish a draft or succeed in making it the best it can be. That’s when I start crossing out a word only to put that same word back where it was. I’ve got a group of stories that is close to being another collection, though I still need a few more entries. I’m not in a hurry. I’ve got a few different novel drafts in the drawer, though I’m not particularly interested in them now. Since this last October, I’ve been in the early stages of drafting a new novel, which means that I’m obsessed with the core of the project but am still looking for the language, the form, and the structure. I had to put that away this summer while I worked on a story that I began in 2019. I revised it radically, and I hope that it’s done or close to done. But I need to get some of my trusted writer friends and readers to give me a verdict on it. At the moment, I’ve got the nebulous novel project at the back of my mind and am working on a story about my time in Berlin, Germany in the early 1990s that I’ve been trying to write for years. Maybe this summer I’ll finally get a draft out.

***

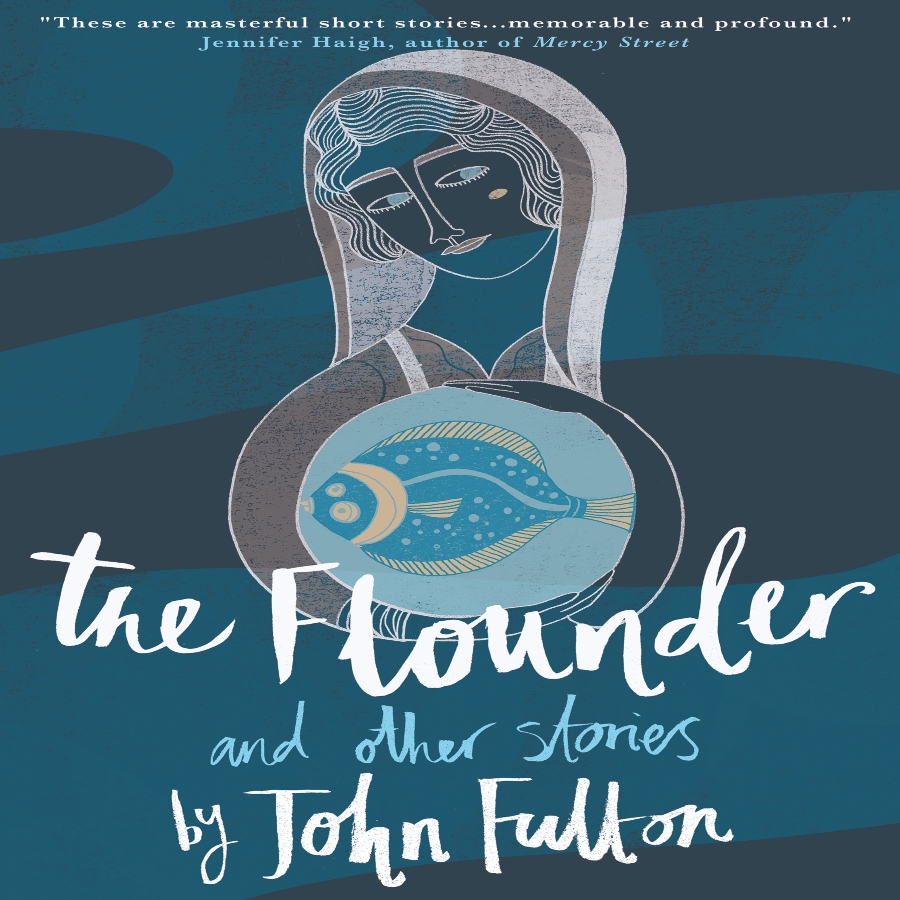

John Fulton’s is the author of The Flounder and Other Stories, which has just been published and is a Poets & Writers Page One New and Noteworthy Book selection, and three other books of fiction: The Animal Girl, which was short listed for the Story Prize, Retribution, which won the Southern Review Fiction Prize, and the novel More Than Enough, a Barnes and Noble’s Discover Great New Writers selection. His short fiction has been awarded the Pushcart Prize and has been published in Zoetrope, The Sun, Ploughshares, and The Missouri Review, among other venues. He lives with his family in Boston, where he teaches in and directs the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Visit his website to learn more at https://johnfulton.net/.

Tommy Dean is the author of two flash fiction chapbooks Special Like the People on TV (Redbird Chapbooks, 2014) and Covenants (ELJ Editions, 2021), and a full flash collection, Hollows (Alternating Current Press, 2022). He lives in Indiana, where he is the Editor of Fractured Lit and Uncharted Magazine. A recipient of the 2019 Lascaux Prize in Short Fiction, his writing can be found in Best Microfiction 2019, 2020, 2023, Best Small Fiction 2019 and 2022. His work has been published in Monkeybicycle, Laurel Review, Moon City Review, Pithead Chapel, New Flash Fiction Review, and many other litmags. He has taught writing workshops for the Gotham Writers Workshop, The Writer’s Center, and The Writers Workshop. Find him at tommydeanwriter.com and on Twitter @TommyDeanWriter.