“He’s bleeding out!” These words stampede through the air, disembodied from their owner. “Somebody help him!”

I stand on the museum steps. When the words reach me, I am unsteadied by their desperate velocity, and I wobble on the bottom step.

I hope they have reached ears besides my own, but the green lawn abutting the museum, usually speckled with undergrads, is empty. For reasons I can’t understand and will dissect later, I move toward the voice.

Around the corner of the museum entrance, I find a woman with her back to me, kneeling on the grass as she holds a phone in trembling hands and dials 911.

She sees me, and gasps.

“He’s bleeding out,” she says softly now. “Help him.”

In front of her, a man lies on a red blanket. His eyes are closed and his lips are slightly parted. I gawk, stupidly, letting seconds pass. Professor Liang’s words are in my head: Don’t just look, Kate, see.

No, it’s not a blanket he’s lying on.

He is lying in a pool of blood.

I note hues of cadmium, carmine, and amaranth. And the smell of earthy rot.

Across his neck, there are two short slits that just barely break the skin. But on the left side of his neck, where one usually goes to feel their pulse, there is a third puncture, this one cavernous and deep, and blood gurgles like a brook through this opening.

“Help him,” the woman whispers hoarsely.

I pat down my body, confirming that I have nothing to apply pressure with. I look at my hands. They handle cancerous turpentine, resins, and pigments all day, but the idea of using them to touch a stranger’s blood feels perilous.

I see two young women gathered, maybe ten feet away. “Can you give me a piece of clothing?” I ask. The one on the left looks disgusted, like I’m asking her to strip naked. The one on the right removes a flannel shirt tied around her waist and throws it to me.

I crumple it up and press it to the man’s neck. I hold pressure with the shirt, and blood starts to soak through. I press harder. When I look up to say thank you, they are gone.

“They’re asking if he has a pulse,” the woman calling 911 says.

Not being able to check his neck as I am practically choking him with the shirt, I feel along his left arm. I can’t find it at first by the wrist, but then there it is. A weak, thready thump beneath my thumb.

“Yes, I think so,” I yell back.

For the first time, I look at the man’s face. He is in his sixties or seventies, with a thin smear of gray, matted hair. He is cleanly shaven. He wears a short-sleeve khaki button-down shirt that is tucked into suit pants with freshly pressed creases. A sunken stomach bows beneath a fine leather belt. In the palm of his open hand lies a small kitchen knife, the kind you use to peel an apple, with an ochre wooden handle. While holding pressure with my right hand, I use my left hand to move the knife away and stick its sharp side down into the dirt.

“They said keep holding pressure,” the woman yells. “They’re on their way.” And then, “Hurry, please,” she pleads into the phone, and reminds them, “There’s a lot of blood here.” The man opens his eyes. “You’re hurting my neck,” he says, but doesn’t move to stop me.

He doesn’t reach for the knife. “Let me die,” he says.

“I can’t, I’m so sorry,” I tell him.

What am I sorry for? The pain I’m causing him? Or for keeping him alive?

And then he slips into unconsciousness again.

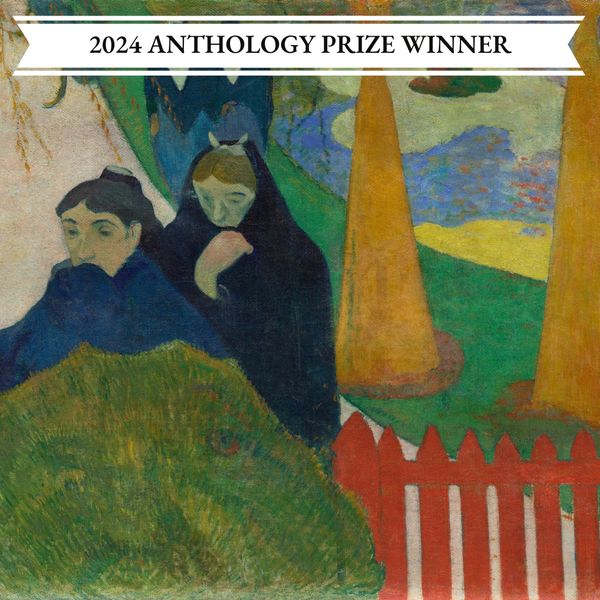

On the orders of my professor, I was here to walk through the Gauguin exhibit for inspiration. On her last feedback form, Professor Liang wrote, “Technically proficient. Completely uninspired.” Last week in class she temperamentally paced as we painted. When she stood behind me, she asked, “What are you trying to say here?” I just wanted to paint things perfectly and beautifully, but so far in my MFA, I have learned only that beauty is the opposite of art. “Nothing,” I told her, defiant. “I thought so,” she said, and walked away.

I resolve to paint him the way I found him.

Yet I fear that the stress of this moment will overwhelm me afterward. I will disremember every detail when I sit down to sketch, and without the details, I will fail.

I take the knife out of the ground and place it back in his hand. Still holding pressure on his neck, I take my phone out of my back pocket. I bring it to my face to unlock it.

The woman who called 911 is leaning against a tree, looking at the ground and rocking gently. By the low wail of the sirens, I can tell they are a few blocks away.

I remove the shirt from his neck carefully. The main wound is no longer bleeding. I bring my phone close to his neck. When I take the first picture, the camera app makes that automatic clicking sound.

The woman looks up, horrified. “What are you doing?” she asks. I don’t say anything. Instead I take a few steps back and take a photo of his face, and then of his body. I am now standing over him, capturing every angle.

“This is disgusting, YOU are disgusting,” she hisses at me.

“You wouldn’t even touch him. You waited for me to get here, just letting him bleed out,” I say calmly.

And then I hear her make a little “Ohhh” sound as she looks down.

He is bleeding again, and now, instead of a slow gurgle, the blood pulses out of his neck rhythmically. I keep snapping.

The sirens grow louder. There isn’t much time left.

Any second now, help will arrive.