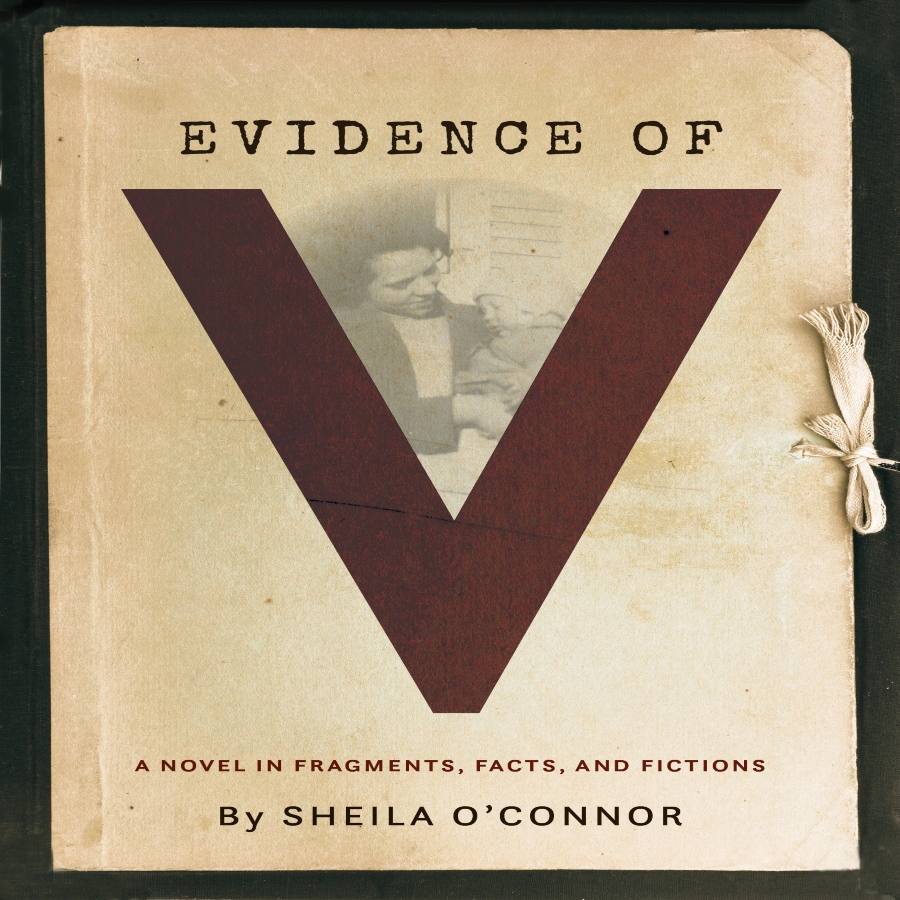

“There is always a wicked secret, a private reason for this,” a line from W.H. Auden’s “Twelve Songs, VIII” came to mind when reading Sheila O’Connor’s Evidence of V: A Novel in Fragments, Facts, and Fictions (Rose Metal Press, 2019), an elegant and ambitious melding of family secrets, historical documents, re-imaginings, and an unsealed case file from the courts.

Evidence of V is a compelling, near-poetic approach to unearthing family and national history by multi-genre, multi-award-winning author, Sheila O’Connor. Readers are immersed in the prose and invited to analyze data, find meaning in the white space, and peer at the injustice.

Throughout this nonlinear collection, O’Connor elegantly explores how we try to make sense of secrets through the found, the visual, and the experimental. Her writing—her use of language—is at once brilliant and visceral, haunting and heartbreaking.

What begins as a question: “Who was she,” coupled by a secret revealed when the author was just sixteen-years-old, Evidence of V is about O’Connor’s unknown maternal grandmother, V, mentioned to O’Connor just once, and never again.

In the 1930s, V was a promising 15-year-old singer in Minneapolis with grand aspirations. When she falls pregnant with the much older nightclub owner’s child, she is sent away to a Minnesota reformation home for sexual delinquency. Evidence of V is a delicious blend of biography, history, social and cultural critique, about searching for a woman essentially eradicated by ‘the system.’

With sections titled ‘A Book of Pseudonymns and Lies,’ ‘And Her They Safely Keep,’ and ‘Practical Experience,’ one gets the sense this is a tale of summoning remembrance, while allowing secrets to surface and breathe.

O’Connor braids together a thin case file, her own research, fictions, lyrical prose, questions, documents, and brackets, and more to puzzle together this devastating tale.

With V, I was reminded of my own maternal great-grandmother. Although the location was different (Missouri versus Minnesota), fragments of the story remain similar: a young, unmarried woman falls pregnant. The options remain few. Over time, stories become misunderstood, silenced, the result often buried in trauma. It brought forth more questions than answers, a curiosity and exploration I felt compelled to engage.

Leslie Lindsay: Evidence of V begins with a contemplation about where to begin, where V’s story starts. I find that so emotionally elegant and heartbreaking, too, this idea that we can begin as a secret, a clump of cells, a reckoning, a sealed history, a girl, a prisoner. Where, where do we begin…as a person, as a story? Can you give us a little insight into your inspirations and process?

Sheila O’Connor: For decades, I’d wanted to write a novel about the long shadow cast by my missing grandmother, but I was daunted by the task. First, there was the challenge of knowing next to nothing. Secondly, where to begin the story of an absent life? Birth? Childhood? The years after she was forced to surrender my mother to adoption? Her suicide? I had long charts that hung from ceiling to floor in my office, timelines essentially, and notebooks full of imagined structures. But her story didn’t get written. Oddly, this book arrived unbidden, with the first line in a piece of flash: “She enters the tunnel a little fox.” And there she was again. And the tunnel—the beginning of her life as a dancer, through her incarceration and escape from parole—turned out to be her timeline. But of course, that wasn’t the true beginning. Just as it wasn’t the ending.

Leslie Lindsay: I love how you state that we are ‘living in V’s whitespace.’ Of course, what all of this speaks to is the idea of erasure and intergenerational trauma. While you piece together the facts and bolster them by your (re)imaginings, you do the opposite of erasure, you write her into existence, you allow her to become tangible. I’m curious if you can expand on that, please?

Sheila O’Connor: Despite how long I’d searched for facts, when I finally had them, they failed me. I saw immediately that the facts of her file couldn’t be trusted, just as the historical claims about the girls and their reformation were lies based on institutional bias. And that what I’d wanted, needed, a story that could make sense of intergenerational trauma and where I am today, wasn’t in the so-called “facts.” In the end, I trusted fiction for the truth.

Leslie Lindsay: So much of Evidence of V angers me. It’s not her and it’s certainly not you, but the ‘system’ of maleness, the justice system, the reformation system, how women and girls are often exploited, misunderstood, silenced, and traumatized, still, nearly one-hundred years after V’s time at the Home School for Girls at Sauk Center, Minnesota. Mr. C, the much older father of V’s child, is largely unpunished, yet he had just as much responsibility—perhaps more—in her fate. Would you say that much of this story is about patriarchy?

Sheila O’Connor: Patriarchy is certainly one of its subjects, but the book takes up so many concerns: class, poverty, immigration, reproductive rights, legal rights, the prison complex, adoption, oppression of girls and women, historical truth, intergenerational trauma, power, shame—it’s difficult to settle my attention on patriarchy. But yes, the stories of girls and women victimized by men, and then criminalized for the men’s actions, those are certainly part of our past and present, and V, and her fellow inmates, were clearly punished for crimes they didn’t commit. In V’s case, I’m certain Mr. C’s was not sentenced to prison for six years, or made to work as a servant while paroled.

Leslie Lindsay: For a while, I lived in Minnesota. I found it more progressive than how it was portrayed in Evidence of V. Of course, you are writing about different period in history. Things change. But they also remain the same. While the Home School for Sauk Center no longer exists, echoes of it reside. I’m curious about your experience of walking the grounds of this place, what remains. Can you talk about it, please? Also, how talking about it helps instigate evolution and remove stigma.

Sheila O’Connor: It’s very painful for me to return to the grounds, just as it is to any site where terrible things occurred. This spring they opened the grounds up for visitors, and I think it was a painful return for many of us, but especially so for former inmates. The building where the girls were held in solitary confinement is still standing; I stood inside a cell, saw the thick locked doors, the metal bed, the tall fence around the building. It was horrific. And girls were kept in solitary confinement for months, sometimes on a diet of bread and milk.

That’s the first part of your question. The larger part, the desire to remove the stigma, to bring this history to light, to end the silence—that’s a hope I held onto as a writer. I had wanted this truth told, and I believed there must be others who wanted it unearthed. Survivors and descendants. And I was right. Shame is a great silencer—it essentially insured the history would be buried. And of course, the records were all sealed.

Leslie Lindsay: While reading Evidence of V, I found myself…haunted. It might have been the photographs of the women interspersed throughout the text, how one face reminded me of my own. She could be me, 90 years ago. Even though our stories are different, there is much to identify with simply because we are women and mothers. Can you speak to the way we sort of weave our own experiences into the vignettes you present—the images—and how that invites curiosity and expansion?

Sheila O’Connor: That’s a fascinating question. In the Venn diagram of my life and V’s, I had to look to our commonalities. We’d both been girls. Young, we both had dreams—V to perform, me to write. We’d had friendships. Fallen in love. Been betrayed. We both came from working class families—V’s poorer than mine. The two of us had come of age in Minneapolis, walked the same winter alleys, stood on the same corners. We’d carried children. Given birth. From a young age, I rejected oppressive cultural norms; I felt certain V did too. And of course, I asked myself how I would have felt to be sentenced to six years at fifteen years old, incarcerated far from home, forced into daily labor, paroled as a servant. All of that I drew on to understand the horror of what happened to V, but more importantly to recognize our shared humanity, to write her beyond the stereotype of juvenile delinquent, or “problem girl” to a fully formed human being worthy of love not judgment. I trusted empathetic readers would do the same; I’m grateful that happened for you.

Leslie Lindsay: I returned to the W.H. Auden poem that began our discussion and found it astonishingly elegant and poetic that the speaker is describing events that occurred in 1935-1936, the same years V was institutionalized. He writes,

“At last the secret is out, as it always must come in the end,

The delicious story is ripe to tell the intimate friend.”

–from “Twelve Songs, VIII—April 1936”

My own grandmother was born in April 1936. Have we started with a question, or ended with one? Has the secret been revealed, or is still festering?

Sheila O’Connor: I love this closing, thank you. And thank you for this fabulous conversation. The secret is still festering, absolutely. There were tens of thousands of girls across the United States wrongly incarcerated, and there are thousands of descendants, and their descendants whose lives have been altered by this history in ways they can’t imagine. And yet, the records remain sealed. The truth buried or lost. This is only one story. There needs to be a larger reckoning.

BIO: Sheila O’Connor is a professor in the Hamline University Creative Writing Programs, as well as the award-winning author of six novels. Her recent genre-bending book for adults, Evidence of V: A Novel in Fragments, Facts and Fictions, combines flash forms, archival documents, memoir, and historical research, to reconstruct the buried history of incarcerated girls. Honors for Evidence of V include the Minnesota Book Award, the Foreword Editor’s Choice Award, Marshall Project’s Best Criminal Justice Books of the year, as well as others. Her other books are Where No Gods Came and Tokens of Grace, and her novels for readers of all ages include Until Tomorrow, Mr. Marsworth, Sparrow Road, and Keeping Safe the Stars. Additional awards for her books include the International Reading Award, Michigan Prize for Literary Fiction, and Midwest Booksellers Award among others. Her books have been included in Best Books of the Year by Booklist, VOYA, Book Page, Bank Street, Chicago Public Library, and Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers. Sheila has been awarded fellowships from the Bush Foundation, McKnight Foundation, and Minnesota States Arts Boards. She has been a residency fellow at Yaddo, The Studios of Key West, Anderson Center for Interdisciplinary Studies, Tyrone Guthrie Center, and elsewhere.