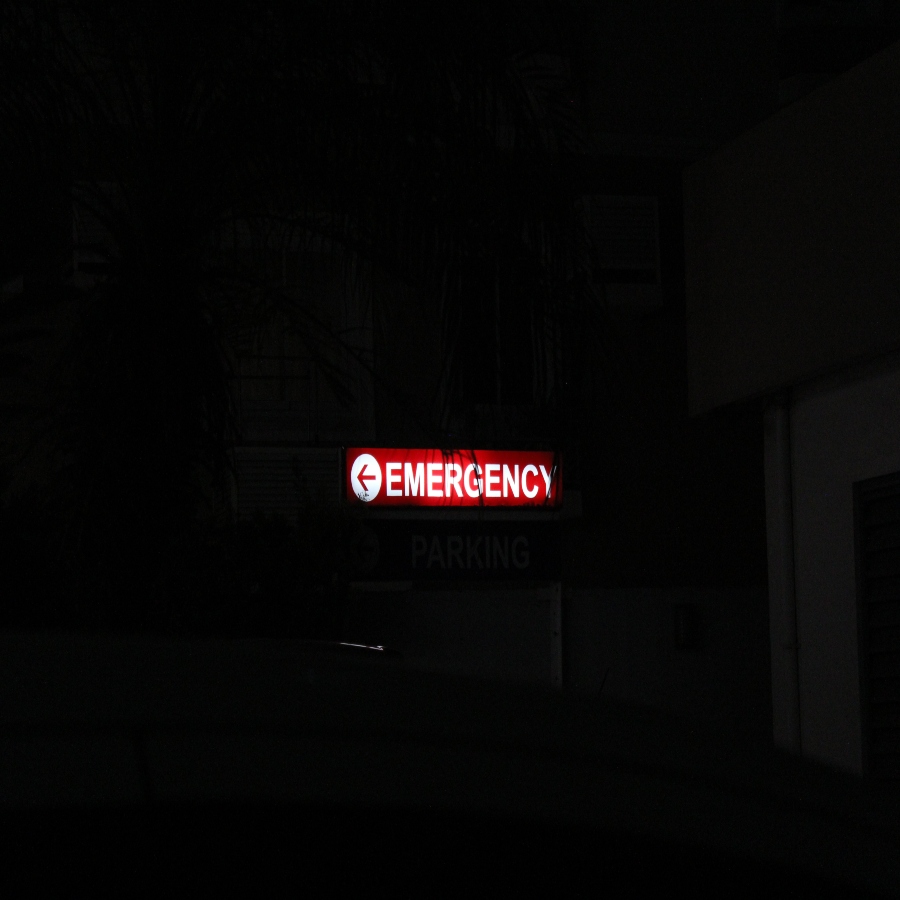

Boy, on the night your mother brought you into this noisy, miserable world, at exactly 11:18 pm, on a rainy Thursday, your father reclined in his Toyota car outside the Emergency Unit and sucked on the titties of a nurse, the same nurse with the pointy bra and four-inch heels who was your mother’s best friend at the clinic during her antenatal classes and always told your mother oh how it was not a stroke of luck that brought the two of them together but a thing our gracious God had arranged—as though she’d spoken with our gracious God in her tiny, musty office lined with shelved paper files that dated as far back as 1978—which was a big fat lie, as your mother’s elder brother worked in the United States Embassy, and the poor sneaky nurse thought that if only she would help your mother jump queues at the clinic your mother would someday return the favour by helping her obtain an American visa, and ahh dear Lord, how the sloe-eyed witch had partly succeeded: she nestled too cosily to your father, held the silly man’s stiffness in her small soft hands, cradling it, and listened to him moan ooh I like that; sweet heavens; go faster, baby; while your mother screamed and screamed, the entire theatre choked with doctors running in a great scatter down the length of the corridors, so that when your head poked out first, all gooey and matted with red, your mother bawled Jesus Jesus and nearly passed out, but a young female doctor stood behind her head, encouraging her—“It’s almost over,” she said, “Push,”—and then you were out, brownish, weighing a few pounds, and your mother muffled her tears, and your father came sprinting towards the ward, his fly wet and unzipped, but the chief operating doctor caught him midway, told him he was a proud father of a baby boy—oh, how your father’s eyes bulged in joy, how he danced in circles round the doctor—and he ran back the way he came, chanting, “Boy, boy,” he did not ask to see you or your mother, for on that same night, he drove to a strip club outside town and had a few bottles of beer—“A few bottles with my friends from the office,” he told your mother the following morning when he returned to the hospital—that left him wasted and drooling by the open gutters, a spectacle for early motorists and passersby, especially the school kids who stopped to ridicule him (all of which the security man at the gate told your mother, but she feigned deafness)—and as your father walked out of the ward, his trousers sagging round his waist, revealing mounds of black, private flesh, he commented on your beauty, boy, the way your eyes seemed half-closed and your jaws stretched taut for a day-old baby and your lips sported a sated smile and your skin that your mother swore she would not let know any brightening lotion, haha, how quickly she forgot that this noisy, miserable world treated beautiful boys differently, hahaha, how uncalculating of her to forget, too, that you would grow so swiftly, but we must tell the story about how she got fed up buying and changing your diapers so frequently, she thought she’d better save money by allowing you to strut around the house naked, pooing all over the place, and this was when she dragged a new house girl into this story—let’s call her Ruth—this girl, your father’s would-be secret girlfriend, who cleaned after your mess and learnt how to handle two jobs in a short space: housekeeping and clandestine late-night romping with the boss, ohh poor Ruth, she worked her way through your watery shit and dirty dishes and never ceased to complain to your father amid a hasty fuck that it was unfair he had refused to take her as his second wife, buhahaha, good gracious Lord, and with your father’s senseless craving for women, one might think you would trudge his path, but no, no, no, you were a church boy, an academic boy, a sports boy—no one could bother if you even cared about girls, in fact, your mother often chuckled to herself, “All these cheap girls will soon begin chasing my dear son. Look how much success and respect he has brought to my family,”—hahaha, poor woman, she did not know that your eyes never strayed to those girls who cooed after you or those girls who forced their hands in yours and begged that you walked them home or those girls who slapped your hard bum when the teachers were not looking, alas, or no alas, as it was not a surprising thing at all, on the eve of your thirteenth year, your mother discovered your father’s affairs with Ruth, an uneventful discovery, as she had returned with you from the market and had found the both of them sweating, clinging to each other, naked, and she had said to you, “Boy, close your eyes,” and she had screamed and fought and wept, and right on your thirteenth birthday, before the clock struck 9 pm, your mother announced that she wanted a divorce, which marked the beginning of the silent cold war in the house, and because you had no one to talk to, it was inevitable that you would spend time with Jude, the shy, brilliant boy who lived on your street and attended your school and miraculously became talkative whenever you visited him, which you liked so much because on your fifteenth birthday, when you told him your parents were no longer separating, Jude the shy, brilliant boy flung himself at you and kissed you and you kissed him back, and in that moment you knew what kind of love would work for you in this noisy, miserable world.

Originally published in SmokeLong Quarterly