by Addison Hoggard | Jun 26, 2023 | contest winner, micro

Step 1: Butter both sides of two pieces of bread. Put mayonnaise on the outside of both.

The crows outside caw his arrival from their nest up the light pole. I can tell they’re talking to me because I’ve learned that even crows sound different when they talk to their young. It’s less of a squawk and more of a grunt. Still gruff, but a sweeter huff. The babies seem to like it. When he enters the kitchen, he says: “Son, make me a grilled cheese.”

Step 2: Put one slice mayonnaise-side down in the skillet.

There are needles in the bathroom. They come wrapped in wads of toilet paper. Doesn’t he know I can see this shit?

Step 3: Three slices of cheese, no more, no less. Put on the other slice of bread.

“Do you remember your momma?” he asks while rolling a joint.

“No.”

He takes a drag. “Do you remember anything about me? Before they put me away?”

“No,” which is true, but I’d heard enough disparaging stories about him from my grandparents, from my classmates, from his old friends. People only talked about him. Never her.

Step 4: A sprinkle of garlic and onion powder.

He says, “I don’t want to get in your way. I just need a place to stay. Get back on my feet.”

“Were you ever on them?”

“On what?”

“Your feet.”

“Help me out here.”

Step 5: Cook until the cheese is melted and the bread is browned, not blackened.

“Your momma used to make the best grilled cheese. When you were born, I swear, that’s all we ate.”

“I never got to try it.”

“What did they tell you about what happened?”

“You were high on something and pushed her out of the car.”

The crows watch through the kitchen window. Their chicks are getting bigger, almost fledglings now. I don’t mind when the parents raid my garbage. It must be hard to provide for so many mouths. I only worry about the needles. I put the grilled cheese in front of my dad and watch him consume every crumb.

He wipes his hands on his shirt. “I’m serious about starting over.”

“So start,” I say.

“I’ll tell you how she made grilled cheese.”

by Dianalee Velie | Jun 22, 2023 | contest winner, micro

-after the paintings, The Baby (1944) and Artist’s Daughter by the Sea (1943) by Milton Avery

Why I chose to enter the world at a time of such violence and destruction, I will never know. But births always come after deaths; adults seem to forget this. It is only we, nameless, faceless, infants, who still hold the memories of the past and the future. We, come tumbling into the future on a bright blue carpet of hope bringing new world views. Why had I returned? I know it was my choice. I looked at the pale pink bunting my mother had dressed me in. Mother was in the other room crying. She had not heard from my father. I knew he would be dead in a few weeks. I had already heard talk of his arrival before I left for Earth. I put myself into my mother’s emotions. I slipped into the future. I thought forward to the day I would wear a dress of almost that same color pink. With matching pink socks, I would be the picture of youthful innocence at the seashore, collecting conch shells while listening to waves echoing the hormonal pulls and tugs in my body. The gulls would hover around me that day, trying to protect my innocence, but I knew it was over. I knew by the way he wanted to paint my picture that he was looking for so much more. Strategically he placed the shells between my legs and my hand between my bent up knees. The world was on the verge of another war, and I was on the verge of losing my virginity. The Vietnam War would not pull the nation together. This one would tear at its very soul. Here I would come of age. We babies, born way back then in 1944, knew this would all come to pass. Knew we would lose our innocence before we were ready. Knew we were a generation that would turn against each other over a war. But yet…. knowing all we did at birth, we still chose to live in hope and forgive the adults who started these wars unbeknownth to us, the innocents who repopulate the earth daily with hope and new dreams and are sacrificed.

by Vic Nogay | Jun 20, 2023 | contest winner, micro

Dear Ginny,

It’s the last night of September. This week, your leaves started to change—darkest green to richest red. Your growth this first year has been miraculous, even for you, my hardy twining vine. I remember planting you in the midnight hours on March 13th and waking late morning to see you had already sprouted. You, grown from seed and the bloody matter I’d expelled when you miscarried inside me. I should have known—you needed to be free.

Pruning is meant to happen in spring when your leaves would grow purple and blue-black berries would cluster and call to hungry birds shaking off their winter chill. But I’m coming tonight with my shears, dear one. I’ll place this letter at the base of the oak you cling to.

I wish beyond wishes that you could release your holdfasts and come down from those branches, walk with two feet into the house with me. All 200 feet of you. I would feed you warm bread and milk and put you to bed with me in front of the fire. I would brush your tendrils as if they were hair while you snored little snores out of some hidden mouth. But the life I hoped to give to you is not the one you’ll have. I grew you here with the same hope of all parents—to one day watch their children grow up, move away, live a life of their own choosing. And although you grow, you cannot go. I never meant to anchor you, to keep you here forever.

Forgive my grand delusions, forgive me my mistakes. I do what I do only to remedy my failures. I will not let you suffer here alone, forever. I cut you down with the deepest ache in my throat and a regret I shall never overcome.

Forgive me, for how I have loved you.

Forever,

Your mother

(Written in wax crayon on kitchen parchment, discovered in the days following her tragic death. Ms. Sorrow was found to be strangled and strung from Virginia Creeper encasing an old oak tree shading the back corner of her vegetable plot)

by Joel Hans | Jun 7, 2023 | flash fiction

But now there are only two brothers and one moon.

At the end of my seven-day shift, I hang the blue lantern on my remaining brother’s door. His whole family is awake, to welcome me back and crater him with goodbyes, and the children smell like creosote, like they’ve been out in the rain. Once they’re back asleep, my brother and I drink liquor made from prickly pear and wait out the three hours before his shift begins. We used to talk about very little, but now there is only one moon, we talk about everything. My teeth ache from our everything, sweetness of that distilled cardinal fruit.

I don’t tell my remaining brother about how, a week before weeks before he emptied the other lantern’s fuel across the desert and sparked a blue wildfire, our gone brother stood behind me and traced my shoulder blades, squeezed a handful of my trapezius, hummed a that’ll do to himself and took into the desert for the last time.

When I return home to my husband and three children, they don’t wake—with my shift is over, we have a whole week to resume our lives before my remaining brother’s shift ends and mine repeats. When I sleep, the remaining moon passes across the night sky, still simmering melt-rock red from where its little brother embraced it too hard after veering off course. After my gone brother scarred the desert with blue wildfire. In the morning, my husband and I collide with each other in bed, him kissing every red pimple where a cactus had once spined me. He charts seven moonrises and moonsets in the pains that cycle my body, but no kiss seals away much of this. Then the children are awake, eager for the week we’ll spend together, to tell me of what I’ve missed during my transit. The storm that stripped the palm trees. The expected breakup. How they counted every star in the night sky. The unexpected breakup. Their intricate weather forecasts for the next twenty-one days, each whispered like a secret.

I wonder if they would follow their siblings anywhere, if they can read each other better than my remaining brother and I could the brother we lost, or, like the moon, they only see half the people they love.

I tide out time to spend with my gone brother’s family. His wife steadies herself against the nearest solid object when his children ask me to play daddy horsey. These children are younger than mine but too old for a game like this; I still fall to the polished concrete floor and let them climb onto my back, one by one by one. They rein me by my shoulders and hair, which must look like their father’s, and when I neigh and rear up on my knees, they cackle so deep they crack, crying, like they’ve forgotten how two moons used to skip across the sky and now there is only one.

At the end of my time off, my husband pins our bodies together next to the firepit and asks if I remember the days just after two moons became one. How the jackrabbits carried the blue lantern across the desert to give us remainders—two brothers, three spouses, nine children—time to mourn and reunite. How we trundled on the mountain trails in a long line and pointed out new-to-us birds, trying to ignore the fire in the sky. Fled to the spastically-lit carnival and cherished the guarantee of the Ferris wheel. Pulled each other from our waxing darks. He always asks if we could do that again: form a different kind of whole. I promise I’ll be back in a week; I almost mean it in full.

When my remaining brother hangs the blue lantern on my front door and lets himself in, I pour two tumblers of prickly pear liquor and lead him into the garage. The vintage two-seater convertible, which the three of us once paid a fortune to have imported to this faraway place, slumbers like a tortoise. For years we meant to restore it together, even though there were three of us and only two seats. When I peel back the cover, a wave of dust, like the debris that coagulated and charred in the sky the night three brothers become two, unfolds between us. We sit on the two seats while he tells me how, during his shift, he fell in love with a mirage and tried to convince a Gila monster to bite him on the neck. How he misses the small blue moon, the way it whistled across the sky, more than he misses our gone brother.

Everything is often too much. Why a moon goes full only once a month?

I leave with the blue lantern. My rendezvous with the remaining moon is an hour’s walk east of where we live. The saguaros tip their crowns and lean out of the path. Roadrunners patter happily alongside me. Burrowing owls unscrew themselves from their tunnels to ask me about my children, who have once again become a single body, moving together, casting my shadow, or casting me in dark.

In the quiet hours, I stare into the blue lantern’s light and wonder how it felt for my gone brother to open the cap and pour its contents across the wands of ocotillo and limbs of cholla that hold starlight in their spines. Whether the fuel burned on its own, or whether he needed a spark. What the remaining moon might think upon rising in the east, seeing another blue wildfire. Would it be as scared as I? Would it wander into a different orbit? Stop to say goodbye? I wonder if it might still ask to stay.

by Kim Magowan | Jun 7, 2023 | micro

For thirty-one of their thirty-two years together, Lydia and Meredith shared an evolving dumb joke which started one day in 1992 when Lydia came home from a rehearsal with a rash on her neck and claimed that she had Tennis Elbow. They would deliver increasingly outlandish maladies with straight faces, even in the midst of for-real pain. Such occurred the night Meredith was going down on Lydia, and Lydia suddenly cried out and clutched her left foot. When Meredith said, “What’s wrong?” Lydia, still clutching her foot, said, “Unicyclist’s Foot Cramp!” That made Meredith howl.

Today, Meredith lets herself into the house, quietly-quietly because Lydia might be resting, but Lydia is lying on the couch, with her eyes open. “How are you feeling, Babe?” Meredith says, and Lydia says, “Meh, Violinist’s Colorectal Cancer.” Without putting down the Walgreens bag, Meredith starts to cry. Lydia says, “Hey, hey, I thought that would be funny! In a kind of meta way? I thought you would laugh.”

“Material to use for your memorial service,” Meredith concedes. But she’s already thinking ahead, to how hard it will be to survive Lydia, how fucking impossible it will be to ever meet someone else with whom to invent and then nurture over decades, beating into the proverbial dust, some ridiculous private joke.

by Tatyana Sundeyeva | Jun 7, 2023 | micro

When the war comes, I do not hear it. There are no planes overhead; It is civil, I am later told. I run through dry grass with other yard children, past creaking play structures, storm-gray walls, and an empty gas silo rusting in the arid field. I fall, clutching my chest, my hand cupping a bee sting.

When the man in the car calls to me, I do not come. I do not like bubble gum. I swing the jump rope in a steady rhythm as acacia petals snow down around me until he leaves, until my turn comes to jump to the beat of clapping children.

When we are stopped by the crowd marching before us, I do not fear. My mother’s hand tightens around mine, but I do not yet know the difference between mob and parade.

When the washing machine barricades our door from the inside, I do not protest. I scramble atop and relish my new perch, a pirate peering from the crow’s nest.

When screams pierce our night, I do not wake. The ambulances are out of gas, but I am dreaming in chartreuse and daffodil.

When we go, I do not cry. I am on my own golden adventure on the platform, peeking out from behind trunks and luggage and the legs of tearful aunts.

But as the train pulls away, the steady rhythm of falling petals, the chartreuse of creaking walls, and the echoes of rusty children growing dimmer in my mind, I am thinking only of my plush yellow horse, alone in the empty rooms we left behind.

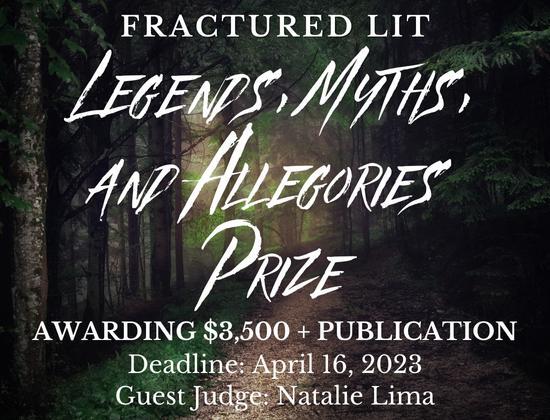

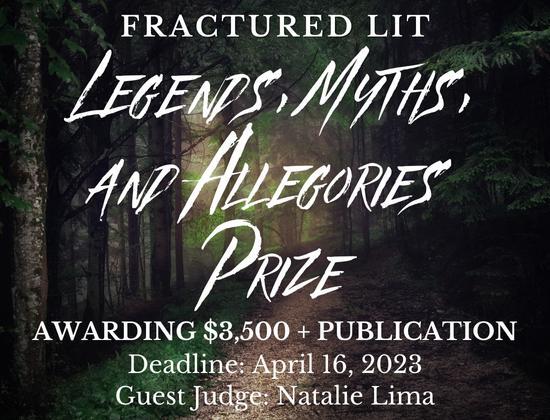

by Fractured Lit | Jun 5, 2023 | news

46 stories on our Longlist! We’re working on selecting our shortlist now, and soon we’ll announce those titles and get the stories off to judge Natalie Lima!

- The Winter Flute

- Leucosia’s Last Song

- Surfacing

- Wild Bill’s Last Ride

- A Visit from Baba Roga

- The Money Pin

- What the Shirt Said

- I Lived Next Door to Cinderella’ – A Neighbor’s Account

- Transition Island

- Another Beatrice

- For Lack of a Better Name

- Cave Sky

- Five Pennies, Blood, and a Dime

- The Philosophy of Weeds

- Leanan

- David Lewis Says

- What’s Missing

- The Sea Witch

- The Martyr

- Seeli

- Milk Teeth

- To Harvest Lavender

- Hearth

- Dawn Along the Strand

- The Cerne Giant in Cold Storage

- The Soul of A Fish: A Fable

- Yrin the Destroyer

- Underdecks

- The Sometimes Gardener

- Alice and the Bunyip

- When The Birds Go Quiet

- In September, When the Sky was an Open Wound

- Ways I Was Born

- Rusalka

- The Trouble with Dating

- Pastoral

- You Can Find Us Near Heaven

- Scurried

- We Could Have Been Warlocks

- Talking Head

- And The Slabs They Dwelled In

- The Dirt Eater

- What Was Left Of Her

- Varying Degrees of Dead

- The Strewing of My Hallowed Parts

- The Fear of Coulrophobia

by Fractured Lit | Jun 5, 2023 | news

We’re excited to name the winner and the runners-up! We’ll publish all three micros in June!

Winner!

Grilled Cheese by Addison Hoggard

Runners-up:

A letter from the thrice-widowed, late Elsbeth Sorrow to the daughter she grew in the garden by Vic Nogay

The Baby Born in 1944 by Dianalee Velie

by Kim Murdock | Jun 5, 2023 | micro

If she’d been a regular girl like Janey, painting her nails whisper pink and talking with an affectation on the phone. Or an awkward girl like Amy, tending to elderly parents, holding down a job at the IGA while keeping straight A’s. Or a weirdo like Naomi, even, doing god-knows-what downtown. But Morana would not be pegged.

She could have unfolded her blanket along the riverside and tipped back the warm, flat beer along with the rest of us. Bathed her perfect limbs in the sun, and later, in her late 20s, develop a benign skin cancer on the fold of her ear, go on to become an advocate for cancer awareness, handing out large-brimmed hats and sunblock along the shoreline.

If she’d fallen instead for the saline lick of the Plant Bath, not a ten-minute walk from her front door. She could have floated for the whole day under the patient wings of lifeguards, buoyant on dreams of family back home, and a time when the sky would stop falling and she could return.

We could have insisted. We could have enlisted Mrs. Dunn to demonstrate the physics of currents, explain how the black glass of the Kichi Sibi is an illusion. When Morana shakes her head in disbelief, we would bring in Mr. Gowanlock, who would pick up his chalk and lay out the complex calculations of time vs. speed vs. rip current and undertow. Calculate probabilities. And when Morana pulls out her Award of Excellence in swimming, we would write and perform a play. It would be in five acts, a classic tragedy, mapping out the river’s sorrows. The time the giant muskie took Willy’s dad’s arm. How Kichi Sibi means great river in Algonquin.

If the water hadn’t kept her whipping around and around as if on spin cycle before pulling her down.

by Erin Vachon | Jun 1, 2023 | flash fiction

Her name was on the Literature of Mathematics & Economics conference roster, attendee badge plucked from the folding table by the time I arrived. The absence of a nametag confirmed her physical presence, hovering nearby. I wasn’t playing that game again. Ancient egos, battling in bed and the classroom. Our sexual dynamics followed Nobel Prize mathematics, overly complex equations on simple relationships. I couldn’t solve us.

We played the same game of dirty Rock, Paper, Scissors over and over. Every round, she won, hands down. If I kept going that way today, in all probability, she would play me again, from the one, two, three, shoot: her scissors slicing my paper heart to shreds. Loving her was tautology itself, chasing my own tail. But by the third panel of the day, there she was, sitting down next to me at the back of a conference room.

Yeah, I felt her elbow, grazing my fingertips. I focused on the mathematician’s voice up front, lecturing on game commitments and credible play, so why not follow the obvious lesson?

Rock me this time.

I pulled away my arm.

A new player took charge, changing strategy.

She stiffened, her breath hitching. She pitched a new move too, pushing back: placed a hand on my knee, aggressive attack. What were we, in a dive bar? I crossed my legs, scissor-snatched my body back, and she was having none of that, the breadcrumb queen herself, tossing loaves at my feet now, pure strategy, over and over, fingertips grazing my earlobe, neck, small of my back, fine, a long time had passed since last she saw me, and I knew a thing or two, too, so I flipped again, covered her arousing rock pelting with paper, looking over, just staring at her, until she felt the execution, how my eyes burned through her, she couldn’t glance back, her rocks collapsing under me, until, all at once, her eyes swooped back up, and I faltered.

Deadlocked.

At the front of the room, the panelists discussed the Nash Equilibria, how two Players — both playing randomly — will never improve their individual gain.

I wanted to control the board. Show me your hand, I mouthed. Show me yours, she whispered.

Palm up, cupped, my hand covered nothing, instead, offered the cruel rocks we once tossed at each other, long after we stopped going to bed together. She touched a vein on my wrist with her finger, and there, she dropped the key to her room.

We left before the question-and-answer portion of the panel, and our stubborn game continued, rocking one another soft this time, we covered up nothing, clothing soon ripped to shreds on the hotel floor.

Recent Comments