I know something is wrong when the spot in the corner of my right eye won’t go away. I was hit until I saw stars, years ago and not by you, but this is different: this isn’t a star but a fuzzy gray cloud. Whenever I read, it floats along with me on each line, blotting out whatever words are coming next. Whenever I slip out of our apartment to get my daily iced coffee—the one treat I still indulge in—it comes with me. I’m glad to have the company, as the streets are mostly deserted these days: blue surgical masks littering the ground like rectangles of stomped-on sky, sirens wailing every few minutes, and each time I go outside it feels like I’m getting away with something. I have only ten minutes to grab my coffee and return in time to fix you breakfast, back into the apartment that smells like somebody’s stale breath. So far away from anything that could be mistaken for the sky.

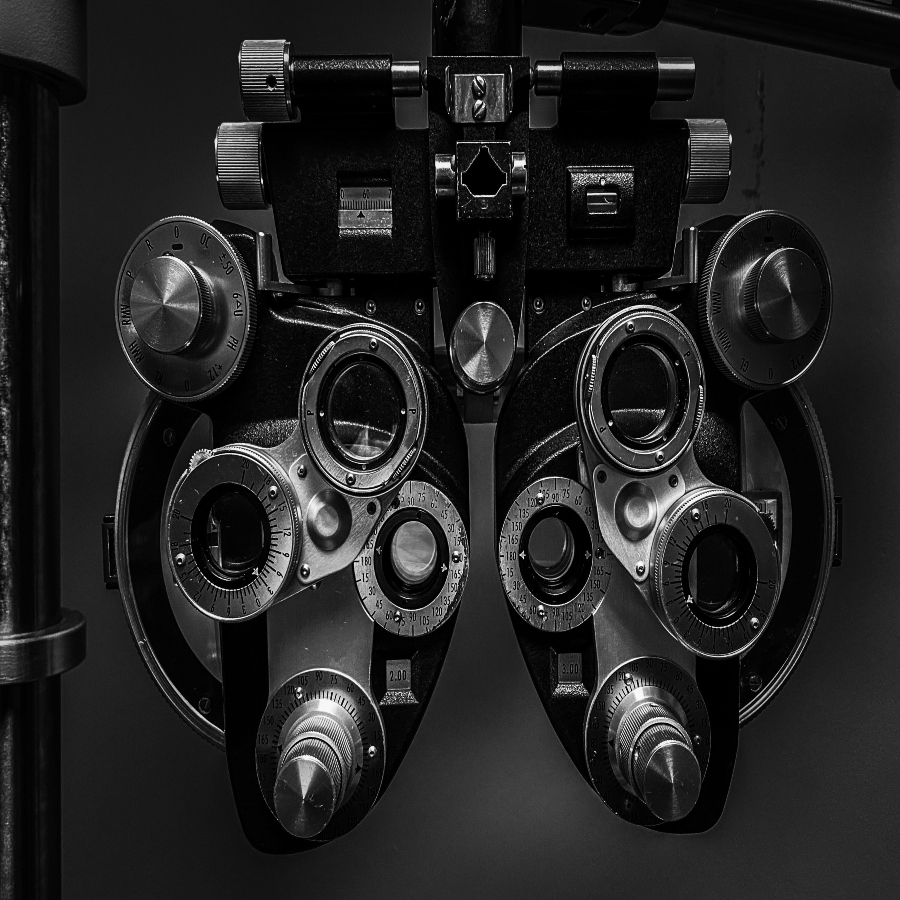

When I finally go to the eye doctor, he frowns and says vitreous detachment, but to me it sounds like vicious detachment. Throughout the whole appointment I find myself thinking of words that start with V: Vandalize, vehement, volatile. (Trite. Predictable.) He tells me to look into a light so bright it makes me tear up, makes my mouth drop open (“Close your mouth” he says in a bored voice), makes my nails sink into my flesh. Victim, voluntary, vaginal. (Now we’re getting somewhere.) In that agonizing light I can see the spiderweb pattern of the veins in my eyeballs, a huge red ghost in the edge of my vision. The pain: something pure about it. So much sharper than your stupid slap.

The doctor takes the light away and asks me how the injury happened. There in the blank white office, both of us just a pair of eyes over our masks, I feel like I can tell him the truth: you got angry when I posted about our relationship problems on Reddit; you said you needed to punish me. The words squeak coming out of my throat. The doctor says “Oh, I see” in the exact same tone of voice in which he told me to close my mouth.

Months pass. My eye heals, and you never hit me again; I think you decided that words would leave more of an impression anyway. On this you may have been wrong. Because on Christmas Eve, I dream that you give me two eight-ball fractures: instead of dull green my eyes glaze dark, blackening into beauty, irises turned to night with blood. When I wake, I run to the bathroom to make sure my eyes are still green—green like mold and pond scum and kudzu, green like things that are living but probably shouldn’t be. The whole morning I keep blinking, keep checking the mirror, keep closing my eyes and expecting to open them bloodied and half-blind. After a while it seems that there is indeed something red and seeping at the edge of my vision. Some kind of optical ghost.

In the afternoon, we take the subway downtown. Surprise beach trip in December but I know better than to ask questions. Your voice sudden as a papercut against my ear: “It’s okay, we’ll still be able to see the tree.” Later I will realize that you meant we can still go to Rockefeller Center in the evening (although we never do), but in that moment, my mind dizzy with vulnerable and vanishing and virulence, I genuinely think you mean that there will be a tree at the beach.

But there is no tree. Just sand ringing cold and clear below the sky, the sound dreamloud, almost violent. A gull swoops down and I raise my face, hoping to tempt it with something—my eyes, maybe—but it sees no spark or glitter, flies on. If I angle my head just right the red in my vision swells and eclipses you. The last four years salt themselves white like winter, disappear. I watch the tide go out and my mouth fills with sand.