The lingering perfume of a million flowers is so thick in the funeral home showroom that invisible rose petals plaster the inside of my mouth. Navy curtains hang heavy and block out the daylight because it really is easier to mourn in controlled lighting without the distraction of bikes and buses and joggers living, fully living the way people do under the big bright yellow sun.

A salesman in the funeral home stands over Mom and me. He’s very sorry for our loss. He understands how difficult these decisions are, but does he actually understand? Has he ever watched someone die piece by piece, one day at a time, or is he like mostly everyone else who backs away because watching someone dissolve taints the memories, so friends and family, every single goddamn fucking person who said, Whatever you need, call, I’m here for you, is just a bag of hot air who I bet will show up at the funeral and mumble how they wish they could have done more. The salesman bows his head, so his shoulders swallow his chin, and in a short, sharp whisper, he calls the urn. Mom is holding a luxury vehicle like it’s some kind of exotic ship. The urn is stainless steel. It’s got that cold bluish tint, so it looks sterile. The salesman has a practiced sombre mask, and he knows exactly how long to keep a string of serious silence hanging between all three of us before he asks if we’re interested in knowing how much?

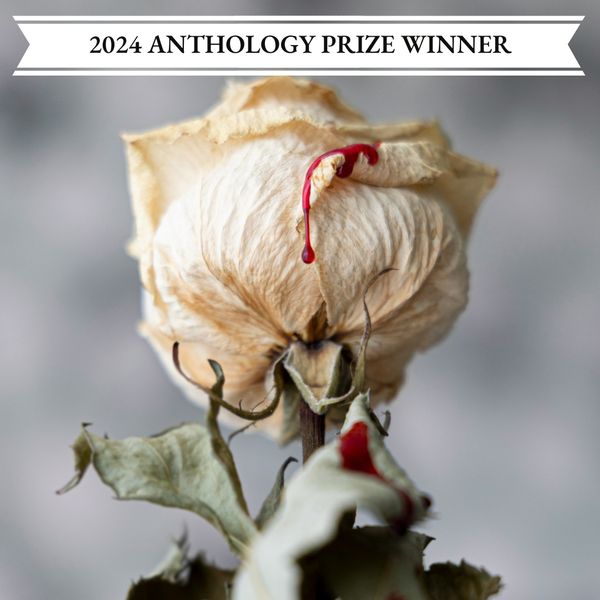

Mom’s laughter starts breezy and light, fluttering through the hushed whispers rising out of the clusters of people choosing between casket and cremation. Her laughter grows out of some mutated clump of cells the size of an orange pushing against her brain. Her laughter swells from breezy into a thundering boom that levels the funeral home showroom like a shock wave, and a woman pawing through swatches of silky casket linings staggers as if some invisible hand pushed her from behind. The woman clings to a man next to her, cowering from the invisible assault. The salesman chokes on a gasp, but he recovers his solemn seriousness and tries to redirect Mom and me back to the luxury vessel’s quality craftsmanship. He doesn’t miss a beat as he launches into reassuring us that the remains will be totally secure once the urn is sealed. The remains. The sealed remains. Mom’s laughter tapers off into a dry, hacking cough. Automatically, I pull a Kleenex out of my pocket in case her eyes start leaking, but it’s not her eyes this time and by the time I get the Kleenex twisted into bullets and pushed into Mom’s nostrils, three drops of blood are streaking down the potbelly of the luxury vessel. The salesman breaks his sombre mask and recoils at the sight of Mom’s blood. It’s probably more life than he’s used to.

A fresh round of hiccupping chuckles is building, and in a minute, hysterics will have Mom doubled over, clawing for air.

The clusters of people in the showroom slap their hands over their mouths. So appalled. So outraged, and my god, we should know better. We should know better! They can’t believe we’d steal their grief. They can’t comprehend this cruel invasion into their very private, very difficult, deeply personal moment, and what kind of people are we? We have no decency. And maybe we don’t have decency because that was one of the first things to go when the mutated clump of cells started pressing buttons in Mom’s brain, and pee dribbles turned to soaked pants and humiliation in the supermarket checkout line while she stood in a yellow puddle, when every single son of a bitch holding their jugs of milk and bags of potatoes, who sit at tables in her diner, her fucking diner!, and know her name and ask about the family, the kids, Any summer vacation plans?, backed away from us like they’d catch whatever she had. I’ll say it again, I bet they all show up at the funeral and mumble about how they wish they could have done more.

Mom flips open the urn, so her airy giggle rings through its hollow belly. She closes the lid and traps her voice like a songbird. I hope the luxury vessel seals her voice forever so I can press my ear to its stainless-steel body and listen to her laugh forever. Soon enough, Mom won’t bother anybody. Soon enough, Mom will be just a collection of fading memories.

“Is there a better time?” The salesman avoids looking at Mom. He pleads with eyes that beg me to get Mom out of the showroom because this is a place for the dead. Can’t I see that?

Mom’s laughter splinters, warbles, and swells into a lump she clears out of her throat like phlegm. “What’s the return policy?” Mom asks.

The salesman’s eyes crisscross from the question, but he tries again to regain control of the sale before the commission on this top-of-the-line urn slips out of his hands. He picks right up where he left off, and the cracks in his sombre mask smooth over, so once again, he understands how difficult this is for us, but “All sales are final.”

Bloody bullets of Kleenex hang from Mom’s nostrils, and no one in the showroom is even pretending not to stare. The woman from the earlier assault forgets her grief, forgets her weak state of mourning, and she rears up like a snake about to strike. The woman dares Mom to snicker just one more time, and she wags the swatches of silky casket linings like she’s threatening a bratty child who could use a good wallop to put them in their place.

Mom holds the urn up to her face, huffs hot breath onto her distorted reflection, and wipes away the streaks of blood with the cuff of her sweater. “Well, I can’t try it on,” she says.