It wasn’t a date exactly. He said, “Do you want to see a dead body?”

I said yes.

I would have done anything to spend time with him. I was a secretary for the medical school, and he was a student. He liked to drop by and talk to me between his neurology lecture and gross anatomy.

It could even be that I suggested it. Maybe he was leaning on my desk between classes, talking about anatomy lab. Armen—he had curly dark hair and a prominent Adam’s apple that I wanted to press my mouth against.

Maybe I said I wanted to see it—the body.

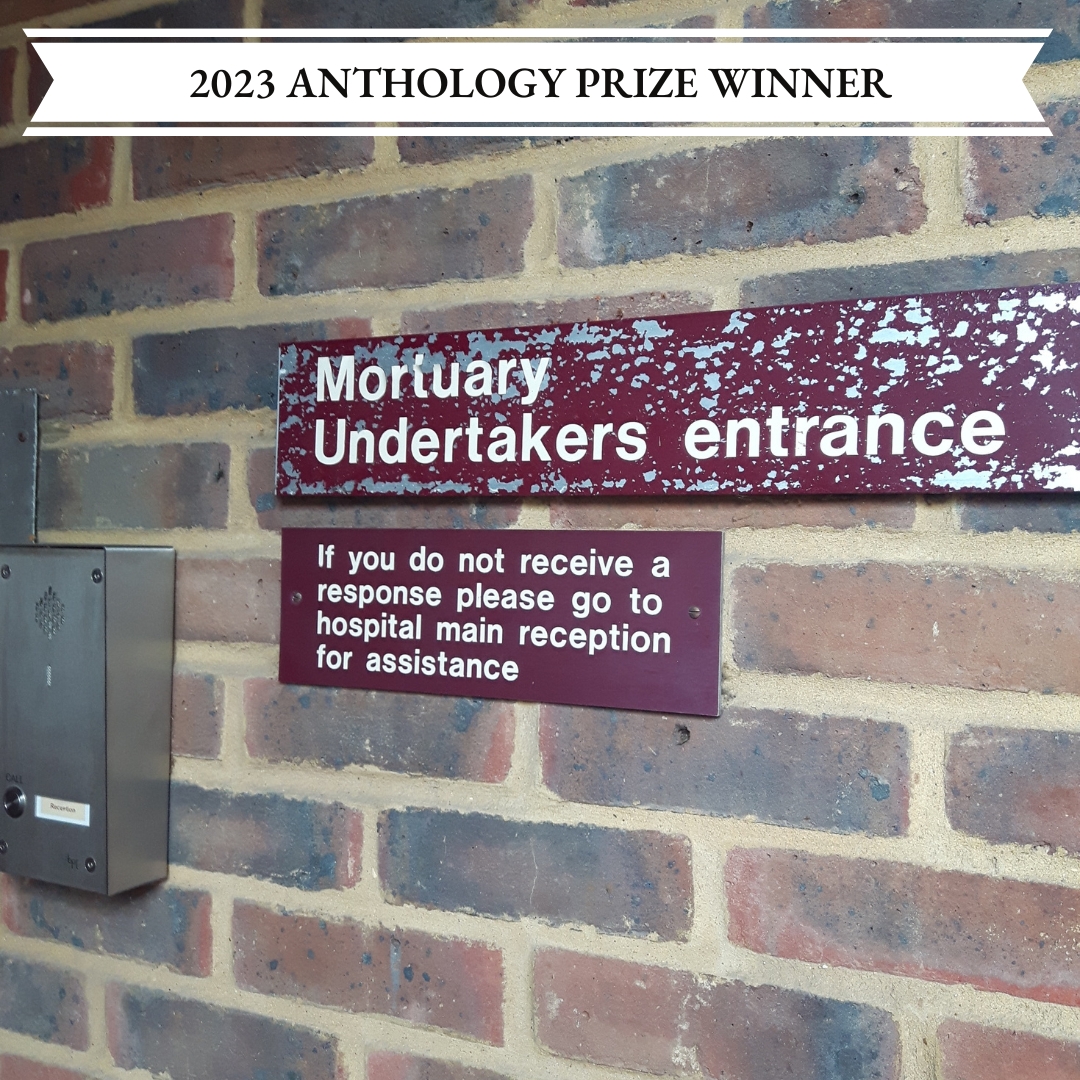

He led me to the lower level of the building. I didn’t even know I was working in a place that housed cadavers. He gave me a blue gown to put on. He tied the strings gently in the back, careful not to touch me.

I could feel him behind me, his breath on my neck.

He said, “Are you ready?” I nodded. The room was filled with what looked like silver operating tables. He pressed a button. The table vibrated, made a humming sound. Two slits opened, and the body rose from underneath, covered in a plastic sheet.

The smell of formaldehyde–I knew it from my own high school anatomy class when we dissected alley cats. The pungent, sharp smell ballooned inside of me, and went straight to my temple, with a needle-like pain.

I took two steps backwards. He caught my elbow. “Are you sure you want to see this?”

“I’m fine,” I said.

He pulled back the sheet. A woman, skin ashy gray. What was left of the skin. You couldn’t even really think of her as an intact body. They were in week 12 of dissection.

I stepped back when I saw her face. It was the lady outside of the Broad and Snyder subway stop, her skin tanned from being outside, wriggly hand-drawn tattoos snaking up her arms like bracelets. She always held the free paper, Streetwise.

Every once in a while, I would buy a copy. That meant giving her a dollar and taking the paper down into the subway with me and then leaving it on a bench in case she ventured down there to get it again. Two for the price of one.

On other days (most days), I would cross the street to avoid her, take the subway entrance on the wrong side of the street so I didn’t have to face her, teeth missing, stumps in her head, the un-prettiness of homeless people, the way they are vulnerable to everything.

I never caught her name, but in my head, I thought of her as Madge. Madge had a series of wigs she wore, a wild, burly one like Harpo Marx, and another one with long hair and bangs; disconcerting to see her from behind with the shiny hair falling down her back, and then to have her turn, a face shriveled up like a dried apple. I presumed that she did all kinds of things for money, that the costumes were part of the way she made her living. It reminded me of a jock in high school who I overheard saying that toothless women give the best blowies. Nice and smooth, he said.

“You see this?” Armen said. “We had to peel back three layers of fat to get inside.” He pointed to her lungs. “Dark spots,” he said. “She was a smoker.” He turned to the chest cavity with its row of rib bones cut across the sternum so they could see inside. He picked up the heart, moved it around in his hands. “Do you want to hold it?” His voice joking, even as he held it out to me.

It was much smaller than I expected. It looked like a decaying avocado.

Armen took her hand in his. I thought he was pretending to hold it, like they were on a date, but he turned the wrist to show her tendons through the skin. “See this?” With his gloved hand, he identified a muscle, pointed, then pulled. Her fingers wiggled. “She’s waving to you,” he said.

I took shallow breaths, pretending to be interested in the white tangle of her intestines. “Do you know her name?”

He explained that most of the donors were either the homeless or the unidentified.

I nodded my head. It felt strange on my neck, loose, like it could fall off any second and roll across the floor. The woman had probably gotten money for donating her body, money she spent on food or clothes or wigs.

“We’re doing the brain next.” He brought me to the front of the body. This seemed better, away from the carnage of the cut skin, the places on her arms where they practiced giving stitches, the split in her abdomen where they sawed away to learn about her uterus. Her eyes were shut, her face untouched. Long black eyelashes, thin lips, a broad nose. She had dots in her ears where her earrings had been removed. “Look at this,” Armen said. He pulled at the top of her head, and her skull opened up, like a jar.

I stayed where I was. I did not want to see the gray curves of her brain. “What happens after?” I asked.

“After?” he replaced the piece of her skull, smoothed her hair back into place.

“When you’re done.”

He bent close to her body, fingers tapping against her rib cage. He had more he wanted to show me, but there was a ringing in my ears now. It occurred to me that he didn’t have the same feelings that I did. She was just part of his lesson.

“I’m not sure what happens to her after.” He looked at me and smiled. “We haven’t gotten to that part yet.”