Beatriz had been insisting since waking that we go to the house at the top of our road, on the rise above the sea. I was barely moving—even a four-year-old should sense something amiss when the full weight of her tugging on each of my limbs has not moved the hull of me off the beached headland of the couch.

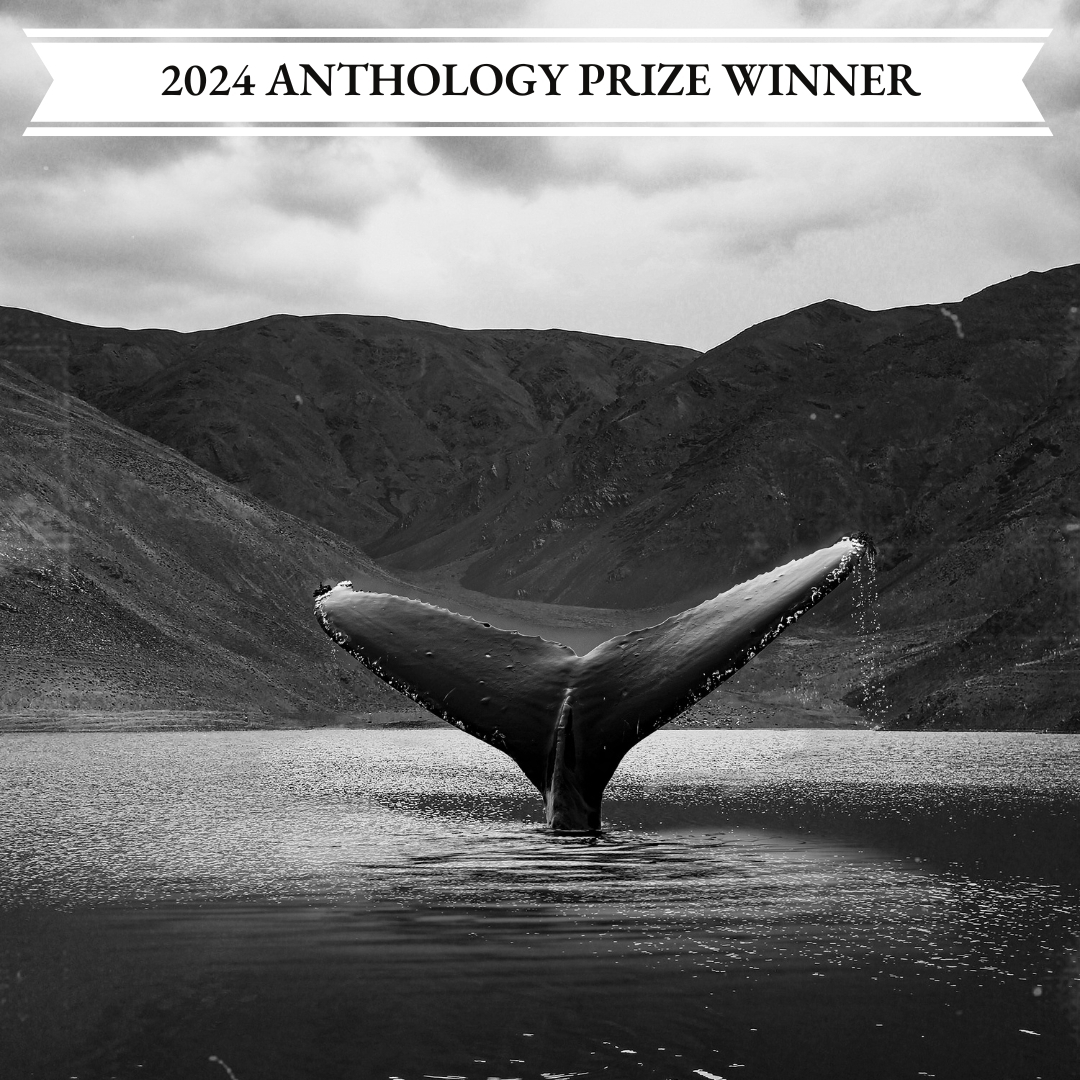

The week before Beatriz was born, a whale beached herself down on the strand, all of us from the estate barnacled, staring beneath the dune, hands covering our mouths each time the great maw gasped its epic exhale in exhaustion.

In my mind, I’m telling Beatriz this story. It is half fairy tale: titian glow of dawn gilding the silky sands of that long stretch of beach in the cup of our bay, all magic and hope. It is half cautionary tale, all the fangs and evil trees and ragged wolf pelts and failed miracles of Grimm.

Our neighbor at the top of the road, Lorna, has hung pictures of angry cats in every window of her house to discourage a chaffinch that had been concussing itself in an effort to kill his own reflection in the glass. Beatriz has seen the cats and is sure they are a sign: she had asked for a kitten. We had a cat, but he’d wandered off. Left me alone with this feral energy balled up and demanding: Beatriz tugs me by the fingers, by my elbows, my feet. “Lorna hung them for meeee… We need to goooooooo, go noowwwwww…”

In my head, I am telling her the exact slate blue of the whale, exact slow rotation of her eye. Gorgeous death, sighing sea air—sky pink—there where our children picked shells and bits of slate, piled turrets and moats. Scientists up from the aquarium told us the whale was healthy. Not yet middle-aged. A mother. A ring of boats had garlanded the bay like some tourist postcard, doing their best to herd the whale’s confused calf, not yet sure how to surface and breathe. Let alone feed. “Selfish bitch!” Lorna had hissed at my elbow. Out of habit, I’d muttered, “Sorry,” without the superstition, yet, to worry that I’d hexed myself. Taken on that sorry and longing and broken navigation and overloaded sonar and misplaced mothering skills. I felt Beatriz somersault in the ever-tighter confines that pushed my entrails into crevices beneath my ribs, felt that giddy tickle of her hiccup, that scrape of glitter and hope. “She is still breathing,” the scientist said of the whale, and Lorna had laughed at me, said I was crying when I answered, “Of course she is.”

Finally, I give in—ask Beatriz, “What is it, love?” Not realizing I’m responding not to her question but her absence. My Beatriz. Her badger-dark eyes. The hedgehog-spite of her hair. Her rabbity stillness and sudden movement. The shrillness of her joy.

She has gone out, gone alone up the street to the house on the corner.

I can’t breathe, of a sudden.

The weight, it must have been. Can you imagine? All your life, the utter weight of you buoyed by the crush of ocean around you. And that one time, that one time, just the once, you think, It would be so nice to lie down. To not swim. Not surface to breathe, not breach, not trap clouds of sardine in a blast of spiraled bubbles. Not nudge the baby, over and over, to the surface. Just. Just lie down a bit. That silken beach over yon. The way it warms with the sun. Just a lie-down, just a minute. Just a rest.

Beatriz comes back down the road to me. All those fears, but truth is, our calves don’t stray, not even when they should. The bounce of light in her auburn crazed halo, the ludicrous rise of her arms like antennae, reaching for the glitter ball above a dance floor, useless for streamlining her run, useless for maintaining balance, all Woo Woo and celebration. Raises a picture in each hand, her miniature parade banners. My neighbor—god fuck me, if it isn’t Lorna—tight-wrapping her cardigan ’round herself, smug and judgmental in Bea’s wake.

“My told you, my told you!” Beatriz singsong chastises, balloon-burst of noise come back in through the door.

I’m on my “good company” behavior now—I’ve sat up, pushed a hand through my hair. Beatriz is in my lap in an instant, the pictures smashed against my eyes so I could see what I was too stubborn to take her to get. Lorna will move more slowly. So much judging to itemize, moving from the open back door through the kitchen. Stacked sink, open boxes, cups upon cups, heaped laundry, dropped shoes.

“It is a cat,” I tell Bea, “I see that.”

“Noooo,” she corrects me, because again I am wrong. Pushes both pictures against my cheeks, presses hard. I might get it then. “Two cats!”

“You are so clever!” I praise her, because we are supposed to affirm our daughters, feed them positive images for themselves from a young age so they can see the full wide range of chances available in their future. My eyes are tracking Lorna. Sounds come from her that are not words. She is my mother tsk-ing. She is my grans.

“Ninety-one tons,” I say, and my beautiful Bea asks, “Is that a lot? Is that how many cats?”

Ninety-one tons, that whale would have weighed once she’d eased herself out of water and onto land. The crush of it. Just for the sake of a lie-down. And all of them, out there in the bay, bobbing in their bright colored boats, heads turned to murmur, “Selfish bitch!” for what she’d done. For what she’d done to that little pale calf out there, cavorting in the waves.