by Elise Blackwell | Sep 30, 2021 | flash fiction

The passion with which she took to the house and garden surprised him. She told him her grandmother taught her to cook when she was a girl. She’d just been waiting for a kitchen. She cooked hard, rolling pastry, stirring sauces with a wooden spoon, punching down yeast doughs and reanimating them with the warmth of her hands. She domesticated what she brought in from the yard, pounding great loose piles of basil or cilantro into pestos, transforming fat figs into glossy jewels suspended in glass jars, reenvisioning weeds into the bouquets that sat between them as they ate what she made.

“You’re an alchemist,” he said, “turning mud to gold.”

She shook her head. “Just a painter of still lifes.”

Outside she seemed tireless, turning the earth with a shovel, releasing its scent, revealing swarming life. The soil crawled with earthworm, ant, and what the child next door called doodlebugs.

When he stepped onto the porch in the summer gloaming to beckon her in, the air was perfumed with just-pruned lavender, rosemary, and mint. Mostly he watched, but from time to time he helped in some small way: putting away her tools, sweeping dirt from the stone pathway, coiling the garden hose according to her directions, its brass head resting in the center.

“Bring your passion to our bed,” he said sometimes, and she always did, the smell of garden still on her, their sex fierce.

It was a cool morning when he heard her cry out and ran downstairs to her. “The gutter was clogged and I was trying to open it,” she said, presenting her arm, the ring finger marked by two red punctures. “Cuts?” he tried, but she shook her head.

“The snake smelled like cucumbers.” She wilted into the passenger seat as he drove her to the hospital. Her hairline was sweaty, her face the strange yellow of dusk coming to a dirty sky when the refineries worked round the clock.

She came home that night with her arm bandaged elbow past fingertips. “We wait,” she said, “and I am not good with time.” For two days she stared out the window. He brought her sandwiches she didn’t touch, milk she did not drink.

On the third morning he awoke to the odor and saw her changing her bandages. The closest thing in his experience was when the neighbor’s dog dug up a weeks-old gopher from the compost pile. Now he tried not to compare the smell, afraid that any analogy would mark it in his memory.

The doctor had thin blond hair and the look of a woman grown suddenly old. Her cheeks and forehead glowed unnaturally red. “A side effect of a medication I’m taking,” she said, pointing to her face. “Not contagious.”

When she unwound the final pieces of gauze and released the smell he turned away—bile already in at the top of his throat.

“Cytotoxins in the venom,” the doctor said, “have caused local tissue death.”

He heard the word amputation and was surprised to hear his beloved ask, “the arm or the hand or just fingers?” as though she were comparing items at the market. In the end, they took the bitten finger and part of another. She cried when she emerged from the anesthesia but was otherwise stoic, taking less morphine than they offered, never complaining of pain or speaking of phantom digits, careful to cover her disfigurement but not seeming to dwell. Yet she did not go outdoors, except from porch to car door and always on the stone path. And she did not look him in the eye for more than a nervous moment.

Six weeks later the garden had gone wild. Tomatoes burst with their own weight, huge basil gone to flower collapsed sideways again the front fence, fruit rotted on the ground, attracting robins, bugs, small mammals that skulked away when he turned on the porch light.

Inside she cooked one handed: grilled cheese, pasta from a bag, soup bought somewhere else and heated, a bowl of grapes grown a continent away.

Upstairs they did not make love, coming only as close as his hand on her back, brotherly, or a workday’s goodbye kiss, lips closed.

One evening they lay on the bed, him in only pants and her in a white gown, watching shadows scrape the ceiling, not touching.

“My hand disturbs you,” she whispered and at last gave him her full gaze. “I know it looks horrible.”

But it was not the way her fingers looked that kept him on his side of the bed. And he knew that if he inhaled she would smell like the lavender mist she sprayed on her face after she washed it, like the mint in the toothpaste from the health-food store, like her beautiful hair. Yet only the stink of necrosis filled his nostrils, and his stomach clenched.

To leave her now would be to admit he is a bad man, one permanently immature, and so he rolls over to make love to her as though she is a person who will not decompose.

Originally published in Newport Review.

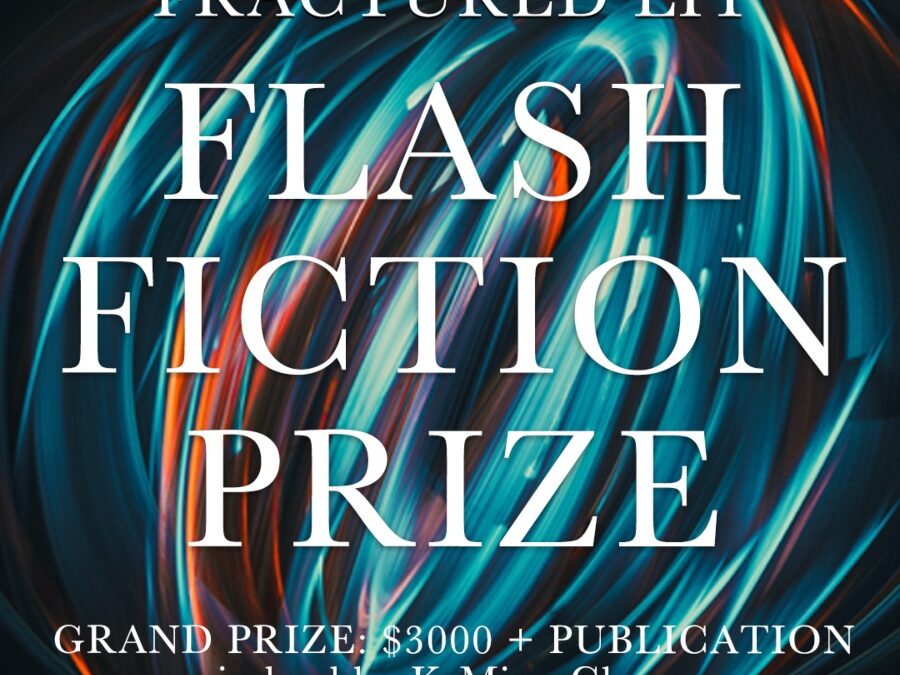

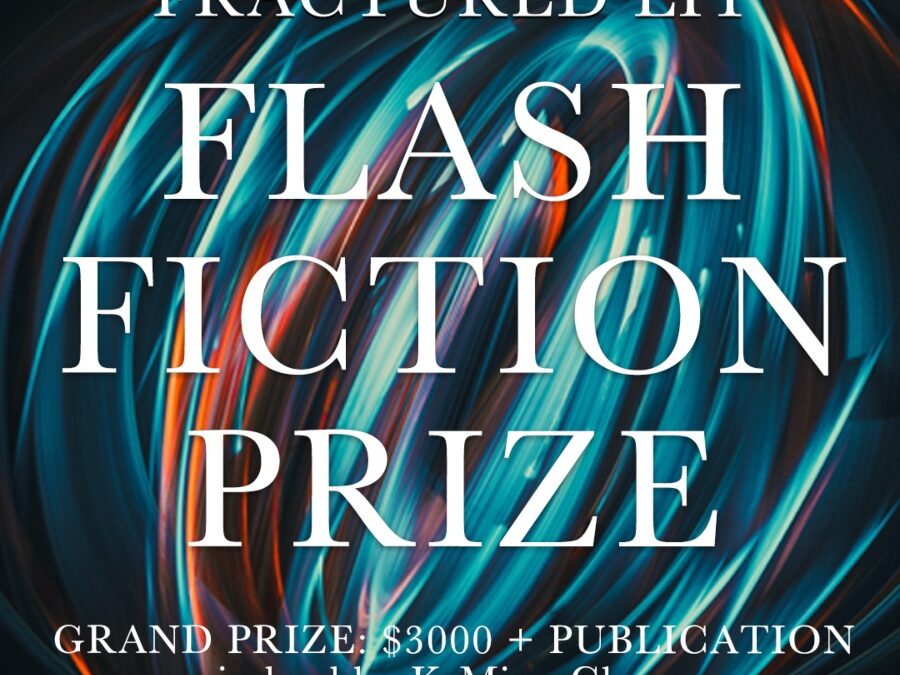

by Fractured Lit | Sep 29, 2021 | contests

fractured lit flash fiction prize judged by K-Ming Chang

closed 7/18/2021

2021 Winners:

1st Place: Everything Will Be Okay in the End by Lindy Biller

2nd Place: Self-Portrait as Everything You’re Not by Jasmine Sawers

3rd Place: Day Trader by Dominic Reed

Honorable Mentions:

A Language Is a Story by Olga Musial

Baby Teeth by Katherine Van Dis

In Memory of Boots by G.C. Gunn

Shortlist:

Somebody Lonely by Marilyn Dees

Other Women by Caitlin McCormick

Easter Morning by William Hawkins

White Powder by E Madison Shimoda

First Comes Love, Then Comes Marriage by Tian Yi

Thoughts Before the Group Session by Peter Hoppock

The Swimming Lesson by Nadia Born

Mother Tongue

A Perfect Facsimile of Flight by Audrey Burges

Nicky True by Kris Faatz

The Grip of a Girl’s Legs by Meg Tuite

How A World-Famous Pianist Arrives At His Venue Where He Plays Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No 2 In A Slightly Out-Of-Tune C Minor by Noémi Scheiring-Oláh

The Trade by Erin MacNair

The Trouble With Quantum by Tong Qiu

Whisper Down The Lane by Mubanga Kalimamukwento

Have Yourself a Merry Little by JSP Jacobs

little piggy and the seven seas by Thomas LeVrier

Pioneers by Shannon Bowring

Robot You by Heidi Kasa

The Four Worst Paint Names We Came Across At Home Depot Upon Failing To Pick A New Color For The Empty Spare Room by R.S. Powers

We invite writers to submit to the Fractured Lit Flash Fiction Prize from May 15 to July 18, 2021. Guest judge K-Ming Chang will choose three winning stories from a shortlist. We’re excited to offer the winner of this prize $3000 and publication, while the 2nd and 3rd place winners will receive publication and $300 and $200, respectively along with publication.

K-Ming Chang is a Kundiman fellow, a Lambda Literary Award finalist, and a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree. She is the author of the New York Times Editors’ Choice novel Bestiary (One World/Random House, 2020), which was longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award. Her short story collection, Gods of Want, is forthcoming from One World in June 2022. More of her work can be found at kmingchang.com.

Fractured Lit is looking for flash fiction that lingers long past the first reading. We’re searching for flash that investigates the mysteries of being human, the sorrow, and the joy of connecting to the diverse population around us. We want the stories that explode vertically, the flash that leaves the conventional and the clichéd far behind. Fractured Lit is a flash fiction-centered place for all writers of any background and experience.

guidelines

-

Your $20 reading fee allows up to two stories of 1,000 words or fewer each per entry-if submitting two stories, please put them both in a SINGLE document

-

We allow multiple submissions-each set of two flash stories should have a separate submission accompanied by a reading fee

-

Flash Fiction only-1,000 word count maximum

-

We only consider unpublished work for contests-we do not review reprints, including self-published work

-

Simultaneous submissions are okay-please notify us and withdraw your entry if you find another home for your writing

-

All entries will also be considered for publication in Fractured Lit

-

Double-space your submission and use Times New Roman 12 pt font

-

Please include a brief cover letter with your publication history (if applicable). Please mention any content warnings as necessary to protect our readers!

-

We only read work in English

-

We do not read blind. The judge will read anonymously from the shortlist.

by Joy Guo | Sep 28, 2021 | flash fiction

Five hungry blonde girls, sitting pertly on their haunches, holding court in the lounge. You all live on the same floor in the freshman dorm, go to the same classes, but still you take their orders. Marcie, the leader, asks, “You don’t mind, do you?” Of course not. Makes sense why it has to be you. She wants the hot and sour chicken, but, oh, can you please tell them not to slather it in sauce like last time. Jill and Megan pick from the Chef’s Specials section of the menu, dishes so luxurious, three different kinds of fish and shrimp, you can’t fathom ever ordering them for yourself. Rachel chooses the spare ribs – she’ll take a bite from the middle of each one and then toss the whole thing, ignoring the precious hunks of meat still clinging to the bone. And Sam says quietly she’ll have the mixed vegetables, the cheapest thing on the menu besides plain rice or an egg roll. For a minute, your eyes meet hers. The two of you might be more alike than you believed to be possible. But she looks away and, like the rest of them, doesn’t say thank you. You tell your friends you’ll be right back.

The woman on the phone has a rough-hewn accent, “r” and “s” sounds thrusting into “l.” She wants to know if you want extra lice. Closing your eyes, you see her bending over a stack of takeout menus, straining to hear you over the din of oil spitting against hot pans, the radio blaring top 40 hits, the cooks’ fluency in both Mandarin and Spanish smack talk. Her hair is tucked into a low bun, a few grey strands pasted to the nape of her neck. Her fingers are adorned with cuts, burns, blisters from a lifetime of working in a kitchen, unlike yours, which are soft and smooth and weak.

“How long will it be,” you ask, biting back the urge to switch to your second tongue.

“Usually twenty to twenty-five minutes. Your name?”

You hesitate for only a beat. “Marcie. M-A-R-C-I-E.”

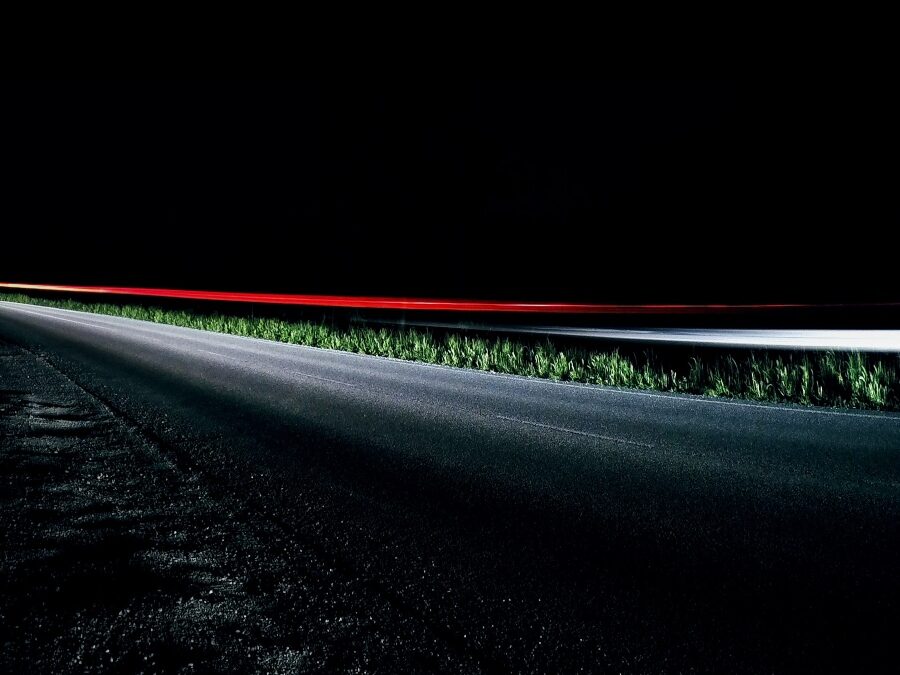

At exactly fifteen minutes, you excuse yourself to use the bathroom. Instead, you wait outside, stamping your feet, rubbing your arms, wondering where the delivery man is. His scooter is almost as old as you are, its gears squeaking in protest, the brake requiring a healthy stomp to lodge. You worry about the day that brake decides it’s had enough, sending the rider tumbling into an unforgiving highway shoulder or against the flank of a car. You worry about him traveling to dimly lit buildings, collapsing from exhaustion. He isn’t so young and strong anymore, this delivery man.

When he finally rounds the corner, the scooter tooting a familiar, weary put-put in hello, you swallow the relief puddling in your chest. He takes off his helmet and smiles at you.

“Jia?”

“You’re late,” you say, reaching for the plastic bag.

Ba doesn’t hear. “I wish I had known this was your order. Ma didn’t say anything!”

The door at the entrance bangs open and you jump, but it’s only a boy from the second floor, who brushes past without looking over. Still, you have a horrible feeling that you had been seen.

“Can you just give me-”

“You look too skinny. Do you not like the dining hall food?”

“Please, Ba, the bag?”

Ignoring you, he retrieves a small bundle from the back of the scooter. It’s a chipped metal canister, one you saw every day growing up. Ba’s dinner pail.

“Here. Ma made it special. You’ll like it.”

And because you know he won’t leave until you take it, you reach over and pry it open. Congee with pork floss, freckles of sesame oil, green scallions, and a cut-up century-old egg. You ate this when you stayed home from school with a fever, saving the best part for last, spooning every drop from the yolk. You loved it. You still do.

Then you imagine those perfectly upturned noses wrinkling, their shoulders curling in disgust, the bottle-pops of laughter.

That looks like hair! Are you really going to eat that?

You’ll have to throw it out.

“Thanks, Ba.”

He hugs you and you wish you can wad yourself up into the lining of his jacket collar. Tucked away there, you can go back to being ten years old. Standing on a stool to reach the counter, poring over the words on the menu, picking out the misspellings. Ma wielding a cleaver the length of her forearm and whacking ribs apart with beautiful precision, Ba handling a wok pulsing with flames as though it’s a loyal pet. You are beside yourself with how much you love them.

But here you are now, with all these friends who are waiting. You shake him off and promise to call this weekend.

As Ba putters away, you don’t look back or wave, but dart inside, bumping into Sam.

“The food arrived just as I was coming out of the bathroom,” you hurry to explain before she even says anything.

“Okay.” She eyes the bundle as you edge towards a trash can. What’s that?

You decide you will show her if she asks.

But she doesn’t.

You can still feel Ba shivering right before he let you go.

“Hey, can you take this food? I need to drop something off in my room. Be right back.”

“Okay,” Sam repeats.

Nor does she ask why you never want anything when the girls order takeout every Friday from that Chinese restaurant. What was the name again? Jade Dragon. Golden Pagoda. Lucky Panda. All the same, anyway.

In the safety of your room, you take out what Ma made. You think of Ba riding alone at night in his thin jacket, with no gloves. The congee is still warm. You lift it up to your mouth.

by Robert Scotellaro | Sep 23, 2021 | flash fiction

Multilingual

We’re in the garden. There are fragrances there, fluent in many languages. Cassie digs, plants, pats the earth. We’ll soon be wedding cake toppers—her lacy gown/my penguin-wear. There are wind chimes, tinkling. They were once blown into a tangle of silence. It took a while to untangle them. Perhaps there is a metaphor here. The story changes. We are continually winnowing it down (what is at stake) like Russian nesting dolls.

Her engagement ring is over an earth-crusted trowel, in league with sunlight. There will be a faint ghost of it on her finger when she takes it off at night. I’m in a lawn chair strumming a ukulele. She wants a baby. I want two dogs and a Harley. “No hurry,” she tells me.

“People pray for a basketful and carry a cup,” she told me once. You could break a tooth chewing on that one. As she goes back into the house, I glance at a rose she’s brushed past, bobbing, then at the accordion folds of her shadow up the steps.

Bachelor Party

The stripper comes in with a behemoth in tow, slices through testosterone thick as whale blubber. She waves off light from her eyes. Someone gets a towel and puts it over the shade of a standing lamp. The dimmer light hides a bruise I noticed earlier, caked with make-up. Many of my friends are married. The “ball and chain” jokes morph into a sizzle with wide eyes on her: “Look-what-you’ll-be-missing” eyes.

The behemoth speaks with a heavy Eastern European accent. He lays out some rules, then holds up a wall with his arms folded. A chair is placed in the center of the room and I’m in it. The striper unzips my trousers slowly like she is revealing the secrets of the universe. We waited this long, so what the hell? Then pant leg by pant leg she pulls off my jeans to cheers. I’m in my tighty-whities. My friends’ expletives are small explosives with confetti inside. The behemoth has a boom box and plays some garment-shedding music on it she finds irresistible. She’s pretty good. And fit. She’s in no hurry. There is a restless shuffling from the watchers and I’m not certain, but I think I hear someone say, “Oh, momma!”

She’s down to just her panties, turns her red-lacy butt to the revved up onlookers. Tony gets up and hollers something unintelligible, so exuberantly, he farts and everyone laughs. The behemoth does a “Sit the fuck down” gesture with his bearded head, and Tony does as he’s told. She makes much of her lap-landing. Circles the runway, then gyrates down. The feverish hooting crescendos.

There is something overly floral about her scent. Not Cassie’s garden. This is olfactory abuse. I feel her breath in my ear: “Now ain’t you the show horse,” she says. It sounds rehearsed. I smell something burning. It’s not cigarette smoke or pot. “Shit,” the behemoth says and turns like a weather vane and rushes to the lamp. The towel is nearly on fire.

Cave Entrance

“Do we really need protection?” Cassie says. “I mean, what are we actually protecting against? Let’s roll the dice. Get frisky.”

We are at a party. It’s snowing out, lightly. Our coats are atop a pile on the bed, slightly damp, and Cassie finds the weighted sum of them inviting. She has stopped taking the pill, says they’re making her moody. We’re using condoms now. I haven’t any. My brother is at the house feeding our two yellow labs. My Harley is in the garage waiting for spring. Waiting to spring. I want Cassie’s arms around my waist and the world to whiz on by us, or seem to, as we whiz on by it. Velocity can air one out. Air two out in all the right ways.

Lately Cassie’s been urging us to make love in odd places. Says she always wanted to make love in a barn, in a hammock, in a mall dressing room. Everyone is in the living room with their drinks and an ooze or riptide of gossip. We are in the bedroom of a close friend. Cassie is staring at the pile of coats and lifts one end. It is dark inside and there is the combined scents of all our friends (natural and unnatural) and a hint of the weather outside. When I was a kid my mother got me a book of snowflakes. A single flake for each slick page. I marveled at the sight of each in isolation. Nearly planetary. Each a unique, irreplicable art.

Currently they are merely damp spots on coats as Cassie smiles, goes to the door/the knob and pushes in the lock button. Goes back and finds another cave entrance. I glance inside. “You’ve got to be kidding me,” I say. There is no end in there, no top, no bottom—only future now.

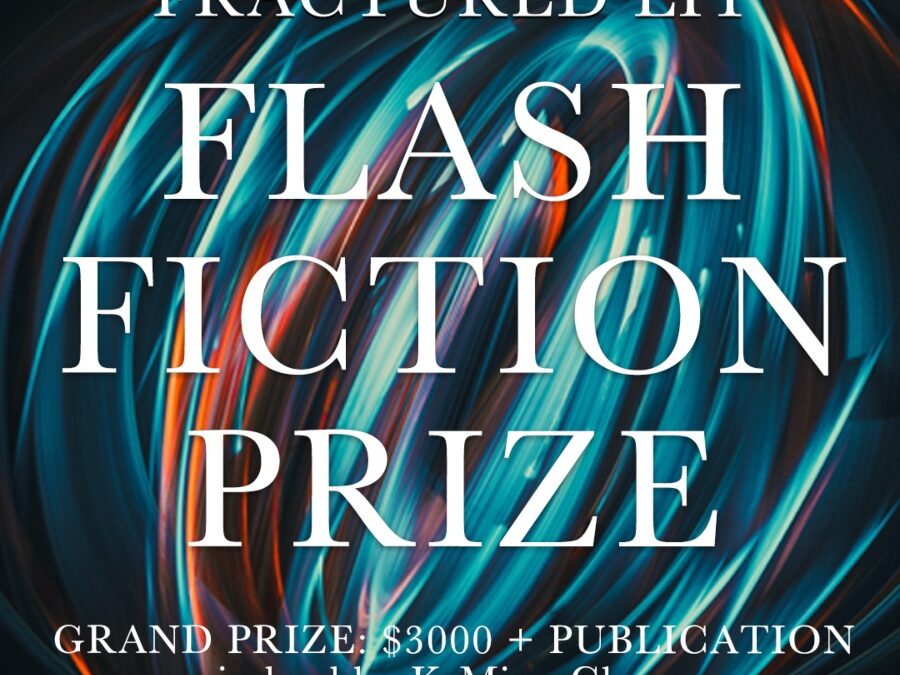

by Fractured Lit | Sep 22, 2021 | flash fiction, news

We’re so excited to announce the 25 titles on our shortlist! We’ll announce the winners’ titles in the next few days! Thank you for your patience! From this list, K-Ming Chang has chosen 3 winners! “I got so excited about these amazing stories that I spent all of yesterday and today reading and rereading them and the ones I chose just really leapt out at me.” K-Ming Chang

Somebody Lonely

Everything Will Be Okay in the End

Other Women

Easter Morning

White Powder

Baby Teeth

First Comes Love, Then Comes Marriage

Thoughts Before the Group Session

The Swimming Lesson

Self-Portrait as Everything You’re Not

Mother Tongue

Day Trader

A Perfect Facsimile of Flight

A Language Is a Story

Nicky True

The Grip of a Girl’s Legs

How A World-Famous Pianist Arrives At His Venue Where He Plays Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No 2 In A Slightly Out-Of-Tune C Minor

The Trade

The Trouble With Quantum

Whisper Down The Lane

Have Yourself a Merry Little

little piggy and the seven seas

Pioneers

In Memory of Boots

Robot You

by Michaella Thornton | Sep 20, 2021 | micro

Baby, when the toast goes cold, the butter will not spread. The daffodil fat just sits on stiff bread. You can make it work, sure. Smear on strawberry jam, mash an avocado, fry an egg and let the residual heat warm you. You can reheat toast and endure endless toughness. Of course, you can bite into sad breakfast, again and again. A breakfast too many are told is marriage. As if women were cereal, a hot croissant. But believe me, honey, at some point just sweep the crumbs into your cupped hand and let go.

by Ra'Niqua Lee | Sep 17, 2021 | micro

We are weary in sweat and heat that settles like skin to skin. Deep in the buzz and whir of small things, dragonflies, mosquito blood suck. We left his car a mile back, broke down again. “What are you giving up for me?” he asks. Accusing is a love right, and any answers feel thinner than shoulders and margins. The old egg and rot smell is a patch of fur in the brush that might have screamed. I never stumble when putting one foot in front of the other. I never scream when confronted. What more to give than this?

by Fractured Lit | Sep 14, 2021 | flash fiction, news

We’re so excited to announce the 52 titles of our longlist! The submissions we received were so original, exciting, and creative that we’ve had a hard time narrowing down the list! We’ll announce the shortlist titles in the next few days! Thank you for your patience! From this list, K-Ming Chang will select 3 winners!

Somebody Lonely

A Bird and My Daughter Is a Blueberry

L and D

Cuba, July 2021

Everything Will Be Okay in the End

100 Million, Oblivion

I Heart Sluts

Other Women

The Perfect Mother

Vemodalen

Easter Morning

White Powder

Story of Your Life

Baby Teeth

First Comes Love, Then Comes Marriage

In the Language of Flowers Hydrangeas Symbolize Gratitude for Being Understood

Thoughts Before the Group Session

The Swimming Lesson

Self-Portrait as Everything You’re Not

Mother Tongue

Day Trader

Strawberry Balsamic Donut

A Perfect Facsimile of Flight

Sand Dollars

A Language Is a Story

Perpetual Motion

Pegged

Nicky True

The Big Comeback

The Grip of a Girl’s Legs

Eddy

How A World-Famous Pianist Arrives At His Venue Where He Plays Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No 2 In A Slightly Out-Of-Tune C Minor

The Water Goddess

Mating Season

The Trade

The Trouble With Quantum

John Wayne

Whisper Down The Lane

Have Yourself a Merry Little

little piggy and the seven seas

Wild Women

Girlhood

The B Word

he said it was like rusting through

Pioneers

Sunbeam Dream

In Memory of Boots

Palpitations

Robot You

The Smoke Out

The Four Worst Paint Names We Came Across At Home Depot Upon Failing To Pick A New Color For The Empty Spare Room

In the Dust of Elephants

by Bronwen Griffiths | Sep 13, 2021 | micro

Francisco looks down the long wintry road. Wisps of mist hang over the dark trees. The sound of the cooling engine fills his ears, click, click, click.

He takes his hands out of his pockets and checks his watch. He will give them fifteen minutes, no more, no less.

His breath steams into the cold air. Six minutes to go.

Why didn’t he leave?

Because. Because.

A vulture drops down from the mountains.

The rumble of a car. A single gunshot. All his time is gone.

The vulture loops overhead. No sound but the tyres on that long road.

by Regan Puckett | Sep 9, 2021 | micro

She’s Splenda-sweet salvation, preened by her parents, who do everything in a -ly way: welcome you hesitant-ly, talk about you loud-ly, watch you knowing-ly before you know why. Your church girl is daisy socks, French braids, smiley-face pancakes. She’s citrus shampoo and vanilla lip balm, your first kiss, only for practice. Every friendship bracelet, a rosary. Every handhold, a new sin. Your heart is an offering she doesn’t want, so God blesses her with a boyfriend. You weep holy water tears, a pure that burns, and baptize yourself in hellfire until every part of you she ever touched is reborn.

Recent Comments