by K. A. Polzin | Aug 3, 2023 | contest winner, flash fiction

I didn’t have any theater experience, but when I saw the ad for background actors for a local play, I thought it sounded fun: wear a costume, stand in the back, get paid $60 a show. I heard they were taking whoever fit the costumes.

The play, it turned out, was outside, in Greenstone Park. It was one of those new immersive theater experiences. I had to pretend to be selling shoes to a customer – also a background actor. We just pantomimed the thing to add atmosphere but not detract from the main cast, who roamed the park while little groups of audience members followed them. Different scenes took place in different parts of the park, and the audience could pick what part of the story they wanted to follow.

The first few nights, I pantomimed shoe sales with Terri: I’d show her different shoes, she’d ooh and aah, or shake her head, or whatever. There was always a stream of people walking by, watching. Then one night, a woman from the audience walked over, picked up a shoe, and tried it on. This was allowed. We were supposed to go with it. I smiled at her obsequiously – I was getting into this acting thing – then leaned down and fastened the strap of her shoe.

She turned her foot side to side, took a look at it in the shoe. “What do you think?” she said.

This was not allowed. Audience members could only speak if an actor spoke to them, and Terri and I weren’t allowed to speak at all. But, I thought, who’s gonna know?

“Pretty snazzy,” I said.

She smiled, pleased to be part of the play. “I’ll take them,” she said.

Our “set” was just a few racks with some shoes that it looked like the props department had gotten from the thrift store. I had to improvise. “I’ll put them on your tab,” I said, something I remembered from old movies.

She nodded at me demurely, as though she was in the same movie, then slipped on her flats, stood, and meandered off, carrying the shoes by their straps like someone at the beach.

Terri looked at me like what the fuck, and I just shrugged.

But I’d broken my maiden. I’d seen how fun this acting thing could be. Now I wanted more lines.

So when audience members strolled by, taking in the pantomimed sideshow, I’d say hello, invite them into our “shop.” They’d browse the shoes, chat with me, all the while looking a bit unsure, no doubt wondering, Is this part of the story? You see, they were always in search of the story, never quite sure which actors to follow, which were going to start speaking.

There was an apothecary on one side of us, a bookshop on the other. Brandon, the bookseller, saw what was going on. He could’ve been uptight, turned us in, but instead, he gave us a conspiratorial grin, nodded his head yes. Pretty soon I saw him chatting with the audience, bringing them into the shop, unshelving the thrift store books, and handing them to his “customers.”

Esther, in the apothecary, looked confused, asked “Are we supposed to be doing that?”

Me: “Not technically.”

She wrinkled her nose. But I didn’t think she’d say anything.

The shoe-selling was fun, but, I thought, I want to be part of the story.

I made a plan with Brandon. We wrote some dialogue for ourselves. When customers came in, after showing them our wares, we’d whisper to them The king is dead. That is an impostor. This drew a lot of excited looks. I could tell our audience thought they’d uncovered the big secret of the play, that they’d done it by being clever and exploring all the little shops.

I still think what happened next was a good thing. It only made the play better, more immersive. If there was a problem, it was because the actors, the professional ones, wouldn’t listen to the audience, couldn’t evolve along with the play.

What happened was this: the king and his retinue were just across from our shop in the Rose Garden performing their usual scene, same as every night, when an audience member called out The king is dead! That is an impostor! The actor-king was caught off guard, looked unsure for a moment, but to his credit, he stayed in character and barked, “Apprehend that man.” Two guards grabbed the man by the arms, theatrical-style, which it was clear was great fun for him. Others wanted in.

The king is dead! That is an impostor! someone else called. Then, from elsewhere: He’s an impostor! Impostor!

It was full-on audience improv. And they were loving it. Only the actors were having a problem. “No, I…” the king said, then ran out of words. A stage manager, uncostumed and holding a walkie, stepped out from behind a tree. I could see things were devolving.

Then suddenly, I just knew. I strode out of my shop, holding my head up imperiously, walked straight up to the king (real name: Jerry), and removed his crown. As I placed it on my head, in my best king voice, I announced, “I am Gerald, brother of the late King, true successor to the throne!”

There were cheers all around and some huzzahs, at least from the audience. Jerry looked miffed. But he only had himself to blame.

I gave a short speech to my subjects while the stage manager was alerting Security. I bowed before they escorted me away.

#

People loved the play that night; there are still seven five-star reviews on Yelp from that performance.

Of course, I was fired. As was Brandon.

Terri is the shoe seller in the shop now. Good for her.

I get it now: it’s not just the acting that I crave; it’s the giving in, the letting it happen, whatever the moment wants, something Jerry will never understand.

by Quinn Rennerfeldt | Jul 31, 2023 | flash fiction

One Sunday morning, I wake up to discover that both of my daughters have turned into birds. The younger—a tow-headed chatterbox, always sidling up to me when I baked, eager to add a spice of her choosing to the recipe—is a great blue heron stalking around the kitchen on reedy legs, probing the drain for fish. The oldest—wise beyond her years, sarcastic, and often mired in thought—is a regal swan, aloof in the living room. I discover our dog on the landing, covered in piss, shaking and whining. My husband has left coffee on my nightstand, still steaming, beside a note: gone for bird seed.

I cup my mug in both hands, letting the heat leach through the ceramic clay into my palms. The pain of the heat centers me. I do not know what to do with two bird-daughters, but instinct tells me I need to be fully human right now. Grounded, present. Other new-agey aphorisms. I consider doing child’s pose, but the fetal position feels more appropriate. I spend a good half-hour curled like a shell on the floating island of my mattress. Breathe like unpredictable surf, doing its in-out thing. The featherlight clicks of talons on the linoleum floor seep under the door, sending panic into my brain. Meditation feels useless when surrounded by girl-bird sounds.

Before today, I would’ve considered myself an amateur birder. I logged bird sightings into my Audobon app as I walked through the park. Got a little thrill when spotting red or blue plumage. But it’s clear I’m out of my element. It’s 9:30 AM, and I realize it’s well past breakfast time. I cautiously peer around the door frame into the kitchen. My heron-daughter is quiet, perched on one leg; she has given up her attempt to forage in the disposal. She studies me with a flat yellow eye. Her beak is the shape of a blade. I sidle up to the cabinet, back pressed to the door, and slowly creep a hand in to grab a bag of bonito flakes. I dump them out onto a plastic fox plate from her toddler years, a nostalgic place setting I could never part with. The plate she used to lick the remnants of cake crumbs from on her birthdays. I set it on the floor and sneak out of the room. I can’t witness this new avian form of eating, with no tongue or teeth in sight. I tiptoe to the living room against the soundtrack of keratin blades pecking plastic.

Swan-daughter is patiently preening, nuzzling through her white feathers, waterproofing her wings, even though the best I could offer her at this moment is a baby pool that has collected dead leaves in our backyard. Or she could join the bird-shaped paddle boats on Stowe Lake, where her glorious plumage would steal the show.

I slowly unveil a piece of bread stolen from the kitchen before I flee. I shred it into small mouthfuls and scatter it in front of me, breathing quietly as she waddles over to eat. She is dainty and careful in her consumption; she doesn’t look at me, but I can tell she is as aware of my presence as I am of hers. Still studious in her new form. I remember reading, once, how aggressive swans are about protecting their nests. One man is rumored to have drowned in a swan attack, a merciless mother beating him relentlessly when he waded too close to her hidden eggs. I am keenly aware of swan-daughter’s sturdy frame, her long, muscular neck. The white feathers a false sense of security, my swan-daughter dressed as surrender. Even as a human, she outgrew physical intimacy quickly; hugs and cuddles turned into squirming away, a shoulder lent for a quick embrace while still leaving bodily space between us. I simultaneously want to stroke her back and flee to “buy bird seed”.

But I’m nailed in place, watching my love change shape into something interspatial, interspecies. My heart downy as velvet. Heron-daughter approaches us both. We stand as a trio, observing one another, balanced like a three-legged stool. I outstretch my hands, crumbed from the bread. I’m reminded of religious iconography, minus the gentle dove or goldfinch. I close my eyes. The funk of feathers fills my nose. I can feel their mouths investigating my palms, equally cautious. All of us, navigating this new relational space. They are moving through the world as reimagined creatures, divine. Leaving me—and my arms, bare of all but freckles and blonde hairs—behind.

As though without thinking, I open the largest window of the living room. Swan-daughter has to bow her head slightly to get through, but she is quickly gone, as I always feared. Her leaving, in the moment, takes on a quality of quartz; held at one angle, it is opaque, a punctureless grief. Tilted, it becomes clear, something that welcomes and reflects the light.

Heron-daughter perches on the sill for a moment, as though considering how I might be feeling. My youngest, my shadow, who would part parents at the playground like Moses parting the sea, always looking for me. She cocks her bird-head in my direction. Her expression reads as apology, or perhaps I’m anthropomorphizing. Then she stretches neck, body, leg, and wing, a giant being. She swoops down the street. Turns the corner where I can no longer see her. I shuffle to the door of their shared room, now childless. A few down feathers nested in the blankets. I plant my feet on the floor and then my palms. Knees perched on the back of my arms, I dip my head, complete a crow pose.

After a time, the doorbell rings. I expect a bird-daughter returned, or perhaps a husband, replete with seeds. But when I open the door, I am greeted by a big blue egg, 3 feet in height. We consider each other in silence for a moment, and then I invite her inside.

by Kim Steutermann Rogers | Jul 27, 2023 | flash fiction

It was the year the flood washed a parade of homes downriver. They called it a rain bomb. Kate’s home was fourth. She followed three other women, unable or unwilling to leave their homes that once lined the largest river on their tropical island. Kate tried her phone, but no calls connected.

Aunty Lani, from the house ahead of her, tossed Kate a rope, and that’s how the four women tied their homes, their lives, their fates together. What a sight. Four houses, all shades of green, headed for a crescent-shaped bay backdropped by lush fluted mountains sliced with waterfalls. Oh, the waterfalls. So many that they looked like icing dribbling down the creases of a pound cake.

There was food and water. Everyone packed disaster kits these days. Everyone filled their bathtubs whenever sirens alerted a pending natural disaster. Everyone knew the disasters were coming more and more often. It used to be hurricanes or tsunamis, but with warming temperatures, extreme flooding had become a more deadly disaster.

It stopped raining by evening. At dusk, frogs climbed onto the women’s decks. Frogs by the dozen, frogs crawling on top of other frogs, frogs seeking rescue and sending the women onto their roofs at sunset, as a full moon rose over the eastern sky, painting it a post-apocalyptic orange-gold.

For dinner, Jodi shared a vegetarian lasagna she’d made the day before with taro leaves and vegan cheese. Kate made a salad from the bag of mixed greens, her last from her ex-girlfriend, the farmer. The women shuttled everything, one to the other, in baskets they hooked to the ropes connecting them.

“Like dessert?” Aunty asked and passed around banana bread with macadamia nuts, the bananas and nuts she grew in what was once her backyard. Stephanie was the practical one. She tossed everyone a lime and said they were good for washing your hands. “Armpits, too.”

At ten o’clock, a phone pinged, and everyone thought they’d floated into cell phone range, but it was just Jodi’s alarm, a reminder to take melatonin before bed. Instead, Aunty passed around a bottle of Patron. “I was saving it,” she said. “But I figure this is as special as it gets.” Stephanie went inside her house and returned with tortilla chips and salsa. “Good to have something on the stomach,” she said.

No one slept that night, and Kate learned their stories, piecemeal, relayed like the old game of telephone. Aunty was going through a divorce, or not, she couldn’t decide. Her husband spent most of his time fishing or racing outrigger canoes, his first love the ocean, a cliche if there ever was one. Stephanie had just lost her dog to cancer. Jodi was a cancer survivor—breast. And, Kate, recently split from her long-time girlfriend, her lease expiring, trying to figure out her next move. As a seasonal field biologist, Kate couldn’t afford to live alone in Hawaii.

Kate tried her phone again. No bars.

No one asked the question that was on everyone’s mind.

When the moon started to arc for the horizon, Aunty ran fishing lines between the houses and baited the hooks with frogs. She’d learned a few tricks from her fisherman husband, she said. With any luck, she’d cube up an aweoweo and make poke for breakfast. “I’ve got scallions,” Kate said, another leftover from her girlfriend. Jodi didn’t eat fish, not after the baby seal died when it snagged a fish off a fisherman’s line, swallowing the hook, too. But she offered chili pepper water.

Just before the moon dropped out of sight, Kate heard the sound of a whoosh and felt a spray of droplets coat her body. A pungent smell lodged in the back of her throat, and she could just make out a humpback whale, a bloom of red expanding around it. As the women watched, another whale one-third the size surfaced. They listened as they heard the whale calf take its first breath. They watched as it nudged its mother’s side and wrapped its long slender tongue around a teat extending from its mother’s belly. The whales rolled around on the water’s surface, sounding shortly after sunrise.

Kate could barely see the island, their flotilla having drifted far off-shore, but she could see the look on every woman’s face. “That deserves more Patron,” Aunty said and sent the tequila around again.

Before they could check the fishing lines and think about making breakfast, they heard it. Whoop. Whoop. Whoop. The women looked up, their hair blowing in the turbulence of the helicopter’s blades. But not a single one stood.

by Arthur Russell | Jul 24, 2023 | flash fiction

Yes, I saw something. I was making my regular Friday night sauce-and-cheese sandwich. It’s like pizza on an Italian bread. When I went to junior high, Fred’s, the pizza place, sold sauce-and-cheese sandwiches at lunch hour for a dollar; came with a Coke, but now I like to have it with a glass of wine. Took nearly 40 years to realize I could make it at home. It’s so delicious. I don’t even bother to make it with excellent quality mozzarella, and I use bottled sauce, but I also drizzle olive oil on the bread and Pecorino Romano. It’s really better than pizza because the bread holds so much sauce you rarely, if ever, put it down between bites. First of all, it’s warm in your hand, and second, you’re going to want to keep eating.

So, I was by the window, which is by the toaster oven, which is where I make my sandwiches, when I saw Alan Hemshaw running through the backyard. Actually, it was the ginger cat running away from Hemshaw that triggered the motion detector that triggered the floodlights, and a few seconds later, Hemshaw came through. I didn’t see his face, but I recognized him by his gait. You can recognize a person by their gait more reliably at 30 yards than any other measure. That’s my theory, anyway, never read about it anywhere. You guys want coffee?

December, it gets dark by 4:30, and the floodlights are very spooky, when they shine up into the pine tree especially. Did you ever hear of David Crosby, from Crosby Stills & Nash? You’re probably not old enough. Anyway, Hemshaw has this tall man’s gait; I was gonna say he reminds me of Neil Young, but then I realized, not really. He’s a tall, wide shoulders, leaning forward kind of guy, looks like he’s eating at the sink even when he’s at a wedding, and he goes running by. I figured he got into it with Jeanette Fiero, the daughter of the retired school superintendent, Jim Fiero. Jim Fiero used to live two doors down from me, and when Jeanette married, she lived up the block the other way, and Hemshaw and me, we’d gone to Nutley High together; we’d meet at the Tick Tock Diner after dates on Saturday nights to compare notes, which is to say to brag, which is to say we lied, so I was very familiar with Hemshaw’s attitudes towards women generally, and to Jeanette Fiero specifically, which is to say, basically Neanderthal. He’d been up Jeanette Fiero’s leggings for 38 years, at least aspirationally, plus one stint before she got married and another last year after she got divorced. You sure you don’t want some coffee? I’ve got crumb cake from Styertowne.

Last year, July 4th weekend, I saw them packing up her Rav 4. I’m pretty certain they were headed to the Shore; at least, when I see someone in a straw hat sliding a beach chair in the back of a Rav 4, that’s what I think. I figured they’re together again, and it had this offbeat, whaddya know vibe as far as I’m concerned, going back, as I say, to Nutley High. In high school, you’d know kids like Denise Santangelo and Dean Mercuris were going to get married the summer after graduation, and now they have grandkids like a deck of cards dropped on the living room floor, but there were others, the near misses, like Johnny Hamnett and Leslie Gaulin. They should have been a couple. Seriously, you’d see them in the hallway, and their heads were almost touching, and he wrote sonnets for her in the school paper, but she had something to prove and he was not the one she wanted to prove it to, which is a shame because she could’ve used a sensitive guy like that, and then there were the ones like Hemshaw and Jeanette Fiero, if you ever heard of slam dancing — probably before your time, too — that’s how Hemshaw and Jeanette Fiero were, a total collision; so it was the ginger cat followed by Hemshaw; they crossed in front of my garage and through the pergola, back behind the Bernhardt’s house, and, I do not believe, with all the fences and swimming pools, that you can even get to Rutgers Place through the backyards the way we did when we were kids, so I don’t know where he went from there, but he was carrying a gun.

by Robert Shapard | Jul 20, 2023 | flash fiction

“The air on Mars—what there is of it—is leaking away,” he said. “About half a pound a second sputtering into space. P-p-poof. Stripped away by solar winds.” He was still in bed reading a NASA report in the Sunday New York Times.

It was a month since she’d moved into his house, more like a cottage, with a tiny yard. They’d dated in college, then hadn’t seen each other in ten years, happened to run into each other and remembered they liked each other. They were still learning how to talk to each other again.

“I got so stoned once,” she said, “I lay on the floor and listened to the air squeaking in the vents all day. I thought I was on another planet. That was about a year after I met my jerk ex-husband.”

He said mp, waited a respectful five seconds, and put his iPad on the bedside table. “Mars’ early atmosphere used to be like Earth’s,” he said, “but it didn’t have a magnetic field like Earth’s to hold it close. Now it’s just wisps.”

It wasn’t working, she thought. Not that she was giving up.

In one motion, she slipped out of her exercise pants and panties, hopped up on the bed, and did a graceful half-roll toward him. “When I think of space, I think of the attic,” she said. “I thought I heard something up there last night, did you?”

He liked to kiss the inside of her knee. She couldn’t understand why but was patient about it.

In college, they’d had only three dates. On the third, he’d given her his engineering society pin and kissed her passionately. She said okay, weirdly pleased. He was not at all bad looking. But by the end of the evening, she was freaked out by the whole idea of the pin and gave it back when he took her home. He shook her hand, shook her hand. And they went on to other people. She’d liked him, though.

Now, in their early thirties, they were both divorced. She was childless, he had a daughter, who lived with his ex in a nearby city. He drove up, or flew up, every other weekend. He was an ecological engineer, worked for Boeing for a while, then went out on his own as a consultant. Lately, all he could get was low-level number crunching. Yesterday he was out at the lake evaluating a small dam, which he said beavers could have built better. She thought beavers were sweet, weren’t that important. Should he be competing with them? Before that, he had a job with a Bay Area steel mill, designing scrubbers for their smokestacks, but got laid off because the political winds had changed. That she could understand. Politics had been her life. She had a poly sci degree, from a good program, was a Democratic party girl (her words), then lost her way, marrying a conservative politician who cheated on her. Ever surrounded by ambition, she’d grown bitter and snarky. After the breakup, she had devised her own recovery program by temporarily working for an animal shelter and training for the Iron Man. She told friends it took an iron will not to bring home a pet from the animal control shelter. She didn’t want to bond with it. Another breakup would be too much pain.

Now, even though they only had three dates in college, they were like old lovers, with new ground rules. They agreed not to talk about love. She let him know how she felt by patting him down before he jogged out to the park, a joke, to make sure he didn’t have his engineering pin with him in case he wanted to kiss another woman. In response, he said, “It’s just chemistry, mine’s attracted to yours.” He had a tin ear, but she could live with it.

Then why was she feeling so nettlesome this morning? His wife and daughter hadn’t lived here for a year, but she felt like any minute, they’d come bustling in the door with groceries or after-school friends.

He had quit kissing her knee, and started working his way up the inside of her thigh. “Is that supposed to drive me crazy?” she said, not meaning to sound snarky.

“No, it’s to drive me crazy,” he said. “Think of me as a spacecraft coming in to dock.”

“I see,” she said. “Are we going somewhere? In space, I mean?” She sighed, “I’m not trying to ruin your day, I just like to make sense of things.”

“None of it makes sense without us,” he said. “It makes sense if we want it to, you and me.”

He eased beside her, head even with hers, pinned her hand comfortably back, his fingers interlaced with hers.

“You sound like some poly sci theorist,” she said.

He fell silent. She’d done it now. Again. Silenced him. His default was to not talk. She squeezed his hand and got no response. It could be over, she thought.

But he said, with effort, “As long as I have you … maybe I can figure out what’s important.”

It wasn’t something her ex had ever said. Or anyone else she could remember. This is a breakthrough, she thought.

She did a dope slap, to keep from crying, “Duh, of course, what’s going to prevent those particles from the sun from stripping away Earth’s atmosphere, too? We have to save our atmosphere. Is there enough oxygen in the spacecraft? We have to dock together.” She was babbling.

He said mp softly in her ear. “You’re a good listener,” he said. “Module coming in to dock. Permission to enter,” he said.

She realized mp was a small laugh. “It’s so polite in space. It’s nice to ask permission first. Am I the spaceship?” she said. “Are you going to knock first?”

He let out a groan, having already entered. He managed to say, “What?”

“Never mind,” she said, “I’ll just keep talking and …\” It seemed right to begin to lose track of what they were saying. “Just keep … keep knocking.”

by Fractured Lit | Jul 17, 2023 | contests

judged by Rion Amilcar Scott

July 21 to September 22, 2023 (Now Closed)

Add to Calendar

submit

And the winners are:

- Sideways by Cassandra Parkin

- Canarsie Zuhitsu by Geri Modell

- Every Thought and Prayer by Stephen Haines

Thank you to everyone who submitted to this contest! We’re busy reading every submission! We announce a longlist in 10 weeks!

This month, we’re launching a new contest for our writers. From July 21 to September 22, 2023, we welcome submissions to the Fractured Lit Elsewhere Prize.

Life–how curious is that habit that makes us think it is not here, but elsewhere.

-V. S. Pritchett.

For this contest, we want writers to show us the forgotten, the hidden, the otherworldly. We want your stories to take us on journeys and adventures in the worlds only you can create; whether you make the familiar strange or the strange familiar, we know you will take us elsewhere. Be our tour guide through reality and beyond.

For the first time, we are also accepting sudden fiction, so we’re inviting submissions of stories from 100-1,500 words.

We’re thrilled to partner with Guest Judge Rion Amilcar Scott, who will choose three prize winners from a shortlist. We’re excited to offer the winner of this prize $3,000 and publication, while the second- and third-place place winners will receive publication and $300 and $200, respectively. All entries will be considered for publication.

Good luck and happy writing!

Rion Amilcar Scott is the author of the story collection, The World Doesn’t Require You (Norton/Liveright, August 2019). His debut story collection, Insurrections (University Press of Kentucky, 2016), was awarded the 2017 PEN/Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction and the 2017 Hillsdale Award from the Fellowship of Southern Writers. His work has been published in journals such as The New Yorker, The Kenyon Review, Crab Orchard Review, and The Rumpus, among others. One of his stories was listed as a notable in Best American Stories 2018 and one of his essays was listed as a notable in Best American Essays 2015. He was raised in Silver Spring, Maryland, and earned an MFA from George Mason University where he won the Mary Roberts Rinehart Award, a Completion Fellowship, and an Alumni Exemplar Award. He has received fellowships from Bread Loaf Writing Conference, Kimbilio, and the Colgate Writing Conference, as well as a 2019 Maryland Individual Artist Award.

guidelines

- Your $20 reading fee allows up to two stories of 1,500 words or fewer each per entry-if submitting two stories, please put them both in a SINGLE document.

- We allow multiple submissions-each set of two flash stories should have a separate submission accompanied by a reading fee.

- Please send flash/sudden fiction only-1,500 word count maximum per story.

- We only consider unpublished work for contests-we do not review reprints, including self-published work (even on blogs and social media). Reprints will be automatically disqualified.

- Simultaneous submissions are okay-please notify us and withdraw your entry if you find another home for your writing.

- All entries will also be considered for publication in Fractured Lit.

- Double-space your submission and use Times New Roman 12 (or larger if needed).

- Please include a brief cover letter with your publication history (if applicable).

- We only read work in English, though some code-switching is warmly welcomed.

- We do not read anonymous submissions. However, shortlisted stories are sent anonymously to the judge.

- Unless specifically requested, we do not accept AI-generated work.

The deadline for entry is September 22, 2023. We will announce the shortlist within ten to twelve weeks of the contest’s close. All writers will be notified when the results are final.

Some Submittable Hot Tips:

- Please be sure to whitelist/add this address to your contacts, so notifications do not get filtered as spam/junk: notifications@email.submittable.com.

- If you realize you sent the wrong version of your piece: It happens. Please DO NOT withdraw the piece and resubmit. Submittable collects a nonrefundable fee each time. Please DO message us from within the submission to request that we open the entry for editing, which will allow you to fix everything from typos in your cover letter to uploading a new draft. The only time we will not allow a change is if the piece is already under review by a reader.

OPTIONAL EDITORIAL FEEDBACK:

You may choose to receive editorial feedback on your piece. We will provide a two page global letter discussing the strengths of the writing and the recommended focus for revision. We aim to make our comments actionable and encouraging. These letters are written by editors and staff readers of Fractured Lit. Should your story win, no feedback will be offered, and your fee will be refunded.

submit

by Emily Anderson Ula | Jul 17, 2023 | micro

I have this dream: We’re back in the church of Santa Margherita de Cerchi. You’ve written a letter to Beatrice Portinari on a receipt for leather shoes—requesting our love last through this life and the next. Me, I don’t pray this way. I go down to the river, which morphs into a highway, and stick out my thumb.

In this dream, there’s traffic on the Arno. Bumper to bumper. Tourists board conveyances.

Me, I just float on my back. I’ve always been easy like that. A man on the bridge mistakes me for a vessel and asks if he can come aboard. He looks like you. An idealist. You’re all the same, really. Searching for a muse.

“All full,” I tell him. This sounds a bit harsh, so I toot-toot an imaginary horn and tip an imaginary hat, compelled to be cordial. A curse.

Up ahead, a woman beneath a parasol points to a rat in the water. “My God, it can swim, Charles!” The gondolier winks at me and shouts, “It’s ah-Mickey Mouse!” His standard joke for American tourists. For some reason, my heart swoons with love for him.

I still think of that day in Florence. An afternoon stop on the rattling train to Lucca. I wanted to see the David, but the replica outside the Academia was just as good, I agreed. I ordered an Aperol Spritz at a café near the Duomo. You said my accent was wrong.

I think of Beatrice. How you would call me by her name. Featherbrained, ethereal Beatrice. So sweetly uninhabited, bless her heart. I can still see you at that altar, where she’s not even buried. This is where I left you. My soul got hungry and wandered off in search of sustenance. It was like kicking off my shoes.

by Alberto Vourvoulias | Jul 14, 2023 | flash fiction

●Suit jacket and pants. White shirt.

●Brown knit tie, too narrow, too long.

●Pocket square, folded and stapled into shape.

●Battered Florsheim wingtips with white athletic socks —a sign of decline.

This is how my father dressed at proper occasions: dinners out, sales calls, any meeting with money on the line. He married my mother in one. Buried her in another.

The duty nurse hands me his clothes and a battered leather briefcase in an overlarge plastic bag. He hadn’t informed me of the procedure. The neighbor he’d enlisted to pick him up afterward called. “Your father is dead,” she said. “I can’t stay. I have to get home to make dinner for my family.”

Father’s body is cold by the time I arrive at the hospital. His skin glistens like bee’s wax, sluggish to the touch, soft and inert. I find my way to the address listed on his driver’s license. The efficiency is hard-scrubbed and pin-neat. It smells of lemons. The bed’s made with a military tuck. There’s a card in a blank envelope on the bare kitchen table. “I Love You” is the pre-printed message. No name. No signature. No instructions.

●Wash the hospital stink out of the clothes.

● Lay them flat on the mattress in the shape of a man.

I’d seen him a handful of times in fifteen years. I sleep on the couch, unwilling to rumple the last careful thing he’d done. In the morning, I force the briefcase with a hammer, after failing to guess the combination. The case was an extension of his body, a portable organ where he secreted treasures.

●Three legal pads, yellow lined paper, unmarked.

●One silver Cross pen, blue ink.

●Two packs of Post-its, one pink, one yellow.

On the rare occasion that he sent me a letter, it consisted of a note affixed to an article torn from a newspaper: “Thought you might be interested.” Or a bill that had lost its way: “This came for you. Opened by mistake.”

●Half-a-dozen sales brochures for hearing aids and vitamin supplements —products he sold but refused to use.

●Mother’s wedding band zippered into a mesh side compartment. Father’s, taken from his swollen finger on the operating table, glimmers in my pocket.

●Keys to the old house, long sold.

●A religious medal, St. Christopher. Must have been a gift from her.

She was the Church-regular; he, the pagan who believed in a God of motion. At her funeral, Father consoled me by saying, “She gets to rest. We keep going.”

I didn’t go far. Back to school, then to a job I would quit and a wife who would leave me. Every Sunday, I joined him for early dinner. We sat across from each other, trusting to silence more than words. We each bussed our own plates and watched the Phillies or the Eagles on the tube. Then, every two or four. Then, not at all.

Father pushed into new sales schemes and territories, each more far-fetched and far-flung. I came to think that it had been us who had died.

●Certificate of Birth, Honey Brook, PA, 77 years ago.

●Honorable discharge —which entitles Father to a flag every Memorial Day. I never asked if he had killed someone for the privilege.

●Last will and testament, duly signed and witnessed, leaving all to me.

The last time I saw you alive, Father, you rang my apartment buzzer without warning in the middle of a hurricane. We chased Ida’s track through Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We drove through wind and rain so thick it lashed like waves. We skirted flooded fields and rolled by homes torn open by fallen branches. We passed great oaks toppled in the mud and vast whirls of uprooted stalks. When I finally got up the courage to ask, you said: “I just thought that it was something you ought to see.”

by Beth Gilstrap | Jul 10, 2023 | flash fiction

Unsecured in the back seat, I stretched my legs out where my sibling usually sat next to me, preaching about personal space, railing on how much I needed to grow up, give them some room, goddamn it. I’d kicked off my shoes like always, and as the good old country, not that new Randy Travis horseshit Papaw never stopped bitching about, played on and on so loud Granny June couldn’t hear herself think, I went upside down at the window, the gray flash of the highway and road weeds whirring by, thinking about what folks did in all those houses—I gave up counting gliders and flags and tarps on rooftops—we were going too fast. Granny June must’ve thought so, too, because she’d grunt every so often and grab the oh shit handle. Mama says I ain’t supposed to call it that or answer the phone with that word neither, no matter what they do, but I wanted to so bad I could feel it coming like how you know when Mama locks herself in her room again, you’re gonna slide the chair over to the fridge and pull yourself up on the counter to sneak handfuls of the good chips in the big can ain’t nobody supposed to touch but Papaw after church. My head felt fuzzy from the vibrations against the glass, and my teeth likened to fall out, too, but I kept up with it, testing, testing my limits, how close I could get to pure misery without whining. We know something about pure misery, we do. Uncle John got electrocuted trying to fix the powerlines after the storm. All it took was one line. One line come down, hit him in the head, and that was that. When they told me what happened, I asked whether or not his plastic hat melted to his head, but I’m inappropriate, and the grownups said it was time to call it a night. We went to the funeral home to hug Aunt Joe’s neck and bring her a bucket of green beans in case she forgot to eat a vegetable with all her sadness. We went to see the body. The vessel. He ain’t in there anymore. We went to pray for his soul. Granny June says not to mention the bit about his soul to Papaw. Their family don’t see it the way we do. I got to light and hold a candle while they talked about what it meant to be a good man and how can’t none of us judge no one lest we’ve walked a mile. I wanted to ask why the preacher didn’t say lest we’ve been up in the bucket, which is what anybody who knew Uncle John would’ve said, but I stayed quiet and watched wax pool on the piece of paper meant to protect our hands. When I closed my eyes and the bright light hit, teeth still rattling in my head there against the window, I couldn’t remember if it was Uncle John or Papaw who told me the way the sun broke through the clouds warn’t no souls going up to heaven; they was just sunbeams and ain’t that beauty enough?

by Fractured Lit | Jul 7, 2023 | interview

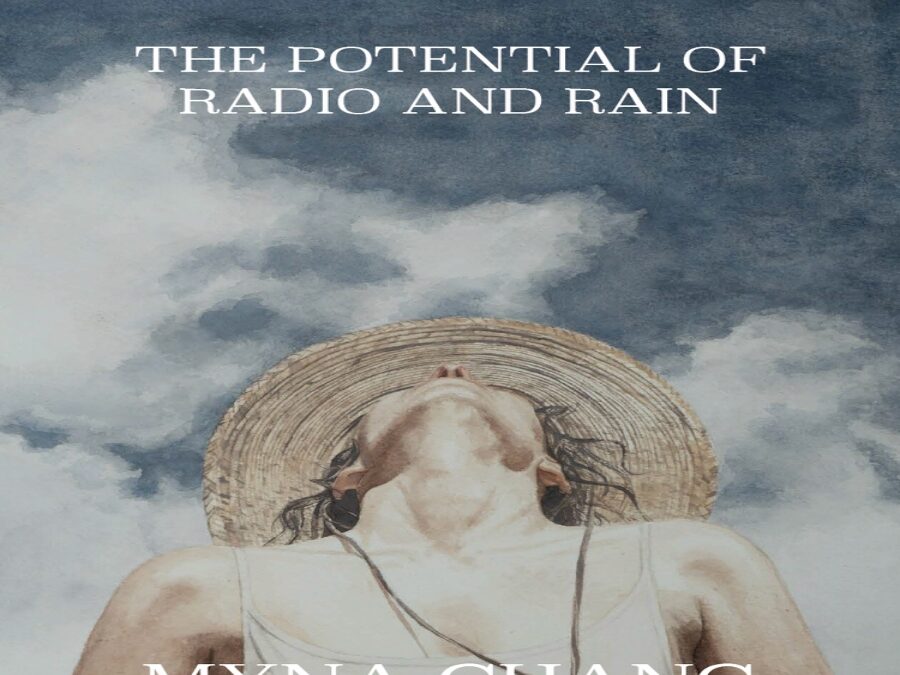

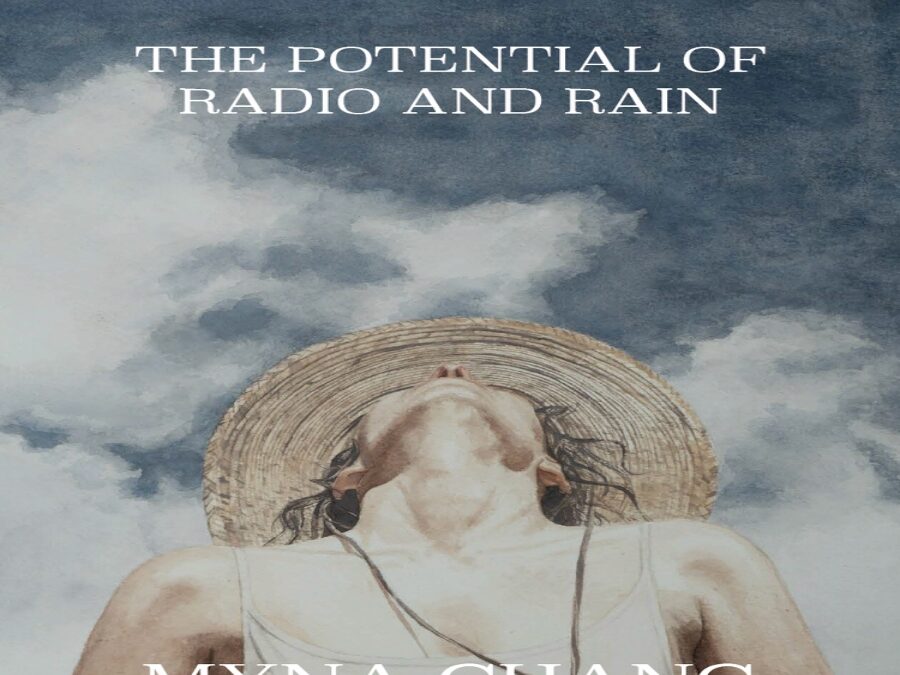

Myna Chang’s new flash collection, The Potential of Radio and Rain (out now from CutBank Books), is a revelation on the ferocity of human need set against the epic forces of nature. Her sentences snap as fast as a cyclone, whipping misfit characters across a prairie landscape to “resonate past the boundaries of this closed life.” Each flash clears away the stale air around human struggle, narrative storm fronts that offer new ways of understanding the world. Ultimately, Radio and Rain lures the reader out of the safety of the emotional tornado shelter in order to engage with each barometric pressure change. Chang and I discussed her lightning-sharp collection through a series of questions framed by storm systems, and her answers blew open the windows on her brilliant collection. ~Erin Vachon

EV: Your characters often yearn to transform into radical forms, like hybrid creatures or runaway storms: “If she had a choice, Grandma would say, she’d forgo Heaven and become a dust devil herself.” Could you speak about the relationship between transformation and freedom when writing your protagonists?

MC: I grew up in a tiny, isolated farm town in the Oklahoma panhandle, where most of us looked alike, and no one was allowed to be unique. Girls weren’t supposed to read science fiction, and boys weren’t supposed to paint landscapes. White girls weren’t permitted to date Mexican boys, and we certainly weren’t supposed to kiss other girls. We never divorced our husbands or started our own companies, and when we got old, we were expected to disappear.

My mother set a strong example by breaking some of these rules — by having the gall to find her unique happiness. Even so, I was very young when I realized I would never fit in.

I can’t go back in time to give myself a science textbook or encourage my friends to date the people they really liked. The best I can do, now, is grant my characters the freedom to live their fullest lives. Maybe that means the jackalope no longer has to hide her antlers or pretend to fit in with the rest of the rabbits. Maybe it means sprouting nightwings and flying away. And maybe my grandma can finally be as free as the wind, even if it is only through a story.

EV: In “An Alternate Theory Regarding Natural Disasters, As Posited By the Teenage Girls of Clove County, Kansas,” the young narrators push back against their surroundings, declaring, “Sometimes, a tornado is just what a town needs.” How did the unbiased violences of storm systems help you reconsider human trauma in this collection?

MC: First, I have to state that I do not believe a tornado is ever a good thing. But I am drawn to the idea of disruption, specifically the disruption of harmful societal systems. In “Alternate Theory,” the storm destroys wheat crops and property, but it also clears space for fresh growth. Teenage girls observe the shifting power dynamics as women shed abusive husbands, launch businesses, and discover unexpected love. The girls get to be the ones to pass judgment for a change, and they like it. They are not going back to the way it was before.

Growing up, I noted the incremental steps toward equality that helped me achieve a happier life than my grandmothers did. I thought we were on the right track! It’s been extremely disheartening to watch the de-evolution of our society over the last decade, especially in rural areas. So, this is my fantasy: a cleansing storm, a freeing wind, to help people see how the “norms” they cling to are often the very things causing their trauma and give them the clarity they need to build something better.

EV: I’m obsessed with the furious “power of the Binding Wind” in “Prairie Alchemy: Advice for the Newly Transformed,” which swells into a dizzy incantation for outcasts. What external limitations are you pushing back against in your work, structurally and thematically?

MC: In terms of theme, I love the idea of diverse people finding each other and building a welcoming community. I see this in my son’s group of friends—teenagers texting and chatting in games, sharing common interests, and recognizing the value in each other’s differences. These kids have grown up supporting each other, and they are vocal in their views of inclusion. They give me hope.

In “Prairie Alchemy,” my goal was to bind such expressions of inclusiveness to the structure of the story. I wanted to weave together a group of micros, with each thread focusing on a different kind of “misfit.” The finished piece is intended to be an interconnected tapestry, where the individual outcasts find safety and belonging in their newly forged community.

EV: Restless teenagers frequently take center stage in this collection, with “the melody of youth woven through the beat of your heart, like limeade thunder on a gear shifter.” What appeals to you about writing that young, whirlwind stage of life?

MC: I’m drawn to the sensation of potential and the lure of the open road ahead—both the brilliance and the folly of youth. Of course, I’m also haunted by nostalgia, especially when I hear an old song. “Limeade Thunder” came to me in a flash, in the parking lot of the grocery store (where most of my ideas take shape nowadays), when ZZ Top blasted out of the radio in my grown-up minivan. The guitar riffs brought back the taste of cheap beer and the discomfort of the long hot drive from our little town to the concert venue 120 miles away. It’s a good memory, but it is steeped in the bittersweet tang of “now I know better.”

EV: In “Hometown Johnnies,” the narrators curse the sky for holding back rain, saying, “We wanted to scream let go! but heaven wouldn’t unleash that water, held it fist-tight, just out of reach.” Your characters struggle against poverty and power, fumbling for release beyond their grasp. If nature showcases the gravity of being human, what hope can writing alongside its forces offer?

MC: In much of the shortgrass prairie, prosperity is intimately tied to weather. The cycle of drought can dictate the course of a life, so it feels natural to me to use drought as a metaphor for hard times. In “Hometown Johnnies,” I wanted to capture the commoditization of the poor and the young, the boys like my step-father, who worked summers in grain elevators or on oil rigs or served in the military in lieu of finishing high school. Jobs that promised a “good enough” wage to live on but that ground them up and spit them out, sometimes literally, were often the only option for boys in my hometown. They hoped they’d be the lucky ones who made it through unbroken, the same way we all wished the thunderheads forming over the Rockies would bring a sprinkle of relief.

Finding hope in the prairie isn’t always easy, but there are moments of beauty. My grandfather thought the morning sun was the prettiest thing in the world, and my dad wouldn’t trade a day in the wheat field for anything. Even though we had to drive two hours to see a doctor or buy a prom dress, we could count the stars in the Milky Way almost every night. Sometimes we did get lucky, and a few of us found our wings. The stories in this collection focus on desperation and stubbornness, but I think they also provide a glimpse of starshine and sunrise.

EV: One last fun question: if you could transform into any storm system yourself, what would you choose?

MC: I’d be that slow shower that comes on a May night when the moon limns the edges of the clouds, and you swear each raindrop is bursting with magic—because it is. Those rains come only once or twice in a lifetime, and you never forget them.

***

Myna Chang (she/her) is the author of The Potential of Radio and Rain. Her writing has been selected for Flash Fiction America (W. W. Norton), Best Small Fictions, and CRAFT. She has won the Lascaux Prize in Creative Nonfiction and the New Millennium Award in Flash Fiction. She hosts the Electric Sheep speculative fiction reading series. See more at MynaChang.com or @MynaChang.

Erin Vachon is a gender-fluid writer and editor, and a Recipient of the SmokeLong Fellowship for Emerging Writers. Their multi-Pushcart, Best of Net, and Best Microfictions nominated work appears in SmokeLong Quarterly, DIAGRAM, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Pinch, and Brevity, among others. An alum of the Tin House Summer workshop, Erin earned their MA with distinction in English Literature and Comparative Literature from the University of Rhode Island. You can find more of their writing at www.erinvachon.com.

Recent Comments