by Leslie Walker Trahan | Sep 23, 2024 | flash fiction

She’s seventeen years old and standing at a bus stop in East Texas. It’s raining, and her hair is pulled into a ponytail. She’s wearing a backpack, and on the bench beside her is a green duffel bag with a broken strap.

The bus is late. Her shoes are wet, and the cold is seeping in through her socks. She looks at her watch and back up at the road. She reaches inside her pocket, feels her bus pass there, two coins alongside it.

Imagine the gas station behind her, the payphone on the wall outside. Imagine her turning toward it, then turning away.

A car pulls up to the curb in front of her. There are two women in the front seat. Imagine the window unrolling, the blonde head poking out. Imagine the duffel bag strap getting caught in the back door as it closes.

But maybe it’s not a car, maybe it’s a truck. Maybe it’s a red one with a man in a ball cap driving. Maybe he’s wearing torn jeans and a mustard-stained shirt. Maybe it smells like rust and rain. Maybe she wipes her wet shoes on a newspaper spread across the floorboard.

Now let’s try a station wagon. Think of the family inside. Two young children, a boy and a girl, in the back. There she is, in the backseat, feeding apple slices to the children. Imagine the couple up front. The woman turning around in her seat to talk. And the man driving, how he bunches up his shoulders and stares at his new passenger in the rearview mirror.

But what if the bus wasn’t late after all? No, that can’t be right. She never made it to California. Imagine the bus stalls out on the way, and when she gets out, there they are. The women, the red truck, the station wagon with the kids inside.

Imagine her sleeping on a too-small couch, her feet crammed under a pillow. Imagine her in a bathtub with a comforter tucked beneath her. Imagine her on the floor, or a chair, or the cab of a pickup truck, the green duffel bag clutched tight.

Maybe she drinks weak coffee in the morning. Maybe she has toast, oatmeal. Maybe there’s a box of cereal, a carton of milk.

Picture her in a red apron, wiping down a table. Picture her restocking cans of beans on a metal shelf. Or maybe she’s pushing the keys on a cash register, sliding change across a counter.

Imagine her pressing coins into a dryer slot, watching her bathtub sheets spin and spin. How long did she stay in the same place? How many people put her up? There was enough kindness, wasn’t there, to last a month or two?

And what about the man? The one outside the restaurant who offers her a ride home. Her boss at the grocery store who says, just one minute, I’ve got something to tell you. The one she saw every day on the bus. The one who always tipped her well. The one who held the door open and said, let me help you carry that inside.

Imagine she fought. Imagine she screamed. Imagine she kicked and tore at him with her teeth.

Or imagine she didn’t. Imagine he was one of the ones who gave her shelter, who turned his head when she took bills from the register or ate a leftover piece of pie.

Imagine she thought, just for a moment, that everything would be ok.

Imagine her throwing up in toilets, paper bags, cups. Imagine her standing in line at the drug store, the small plastic bag she carries home. Imagine her looking down at the blue stick, her fingers going numb when she sees that little line.

Imagine her imagining me.

She’s seventeen years old and standing at a bus stop in East Texas. It’s raining, and her hair is pulled into a ponytail. She’s wearing a backpack, and on the bench beside her is a green duffel bag with a broken strap.

The bus is late. Her shoes are wet, and the cold is seeping in through her socks. She looks at her watch and back up at the road. She reaches inside her pocket, feels her bus pass there, two coins alongside it.

There’s the gas station behind her, the payphone on the wall outside.

And what if she turns away before the car pulls up to the curb? What if the car slows down and then speeds up again when her back is turned, water spraying the spot where she’d just been standing?

Imagine she pulls the two coins out of her pocket and drops them into the payphone slot. Imagine there is someone on the other end of the line.

by Fractured Lit | Sep 21, 2024 | news

We don’t envy Judge W. Todd Kaneko’s challenge of only picking one chapbook from this shortlist! We had the privilege of reading many fantastic chapbooks over the last few months, and we’re sad we can only pick one winner. Here are the titles of the fifteen that make up our shortlist.

- Fish Eyes

- My Years of Blue Violence

- Everything Bites

- Consider the Grease Traps

- Little Knives

- Hurt Me

- Fighting my enemies in the Applebee’s parking lot

- Roll and Curl

- Like Oil and Water

- All the Small Things

- Butterscotch Yellow, short fictions

- Meanwhile, In the Hungry Dark

- You Go Home

- Kaleidoscope

- Jazz Picnic: Very Short Stories

by Debra A. Daniel, | Sep 19, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

This la-de-da woman waltzes in. Skinny. Shiny-lipped. Designer facelift.

Lenny, the crabbiest waiter, with his crater face, his cigarette breath, his lady-I-ain’t-got-all-day shrug, shuffles over to her booth.

She, in her crispness, looks up at him in the space of his wrinkled world. Her face cringes like Lenny farted. He hands over a menu, extra sticky.

“No specials today on account of the kitchen got fumigated last night,” he says, “Coffee?” Already, the pot is in his hand, already tilted toward the heavy, no-nonsense mug, the mug with no finesse, no delicate curve to the handle, no hand-painted violets with their provocative twine of leaves.

The tight-assed woman lifts her hand to stop him before the pour. “Cappuccino,” she says. She sniffs, tries to inhale without breathing in the greasy air around her.

Lenny shrugs and shambles away. “Comin’ right up,” he says, the words tumbling in a mush over his shoulder.

He’s got better things to do. His regulars are here, in their usual places, with their usual orders so that he doesn’t even have to ask, he doesn’t even have to write anything down, he doesn’t even have to refill again and again because he’s left them their own pot of hot coffee on the table. His regulars are his bread and butter, his routine. They make his morning over easy and warm and sunny yellow.

And he’s seen this type before, knows how they want their toast cut into miniature points with those common crusts cut away, how they want the juice fresh squeezed and then sieved to remove the distasteful pulp, how they want their eggs coddled. He knows how they want a cloth napkin and a glass fresh from the dishwasher, and sparkling water and two thin, almost transparent, slices of lime, not lemon. No ice unless it’s finely crushed and catches the light like diamonds.

He holes up behind the counter for longer than necessary, then he brings back a heavier than necessary cup, sets it on the table where the woman is tapping her manicured nails louder than necessary in no rhythm, rather in impatient staccato bursts.

“Cappuccino.” He sets down the chunky mug. One sip, and she’s choking like she’s gonna spew, as Lenny might say. Regurgitate, as the lady might say. Vomir, as she might say if she were in a cafe in Paris.

“You should be ashamed to serve such a vile fluid,” she says. “This would be against the law in France.”

“Lady, it’s diner cappuccino,” Lenny says, “ya gotta understand.”

But this woman doesn’t understand at all, doesn’t even want to. She gathers herself, her oversized purse, her oversized sunglasses, and her oversized huff. She leaves the cappuccino on the table. She leaves no tip. She leaves Lenny without a backward glance.

Lenny wipes down the table, takes the cup back to the kitchen, pours the cappuccino down the drain. He washes his hands, wipes them on his apron. Another customer is in the booth now. He picks up a pot of coffee and shuffles over to take their order.

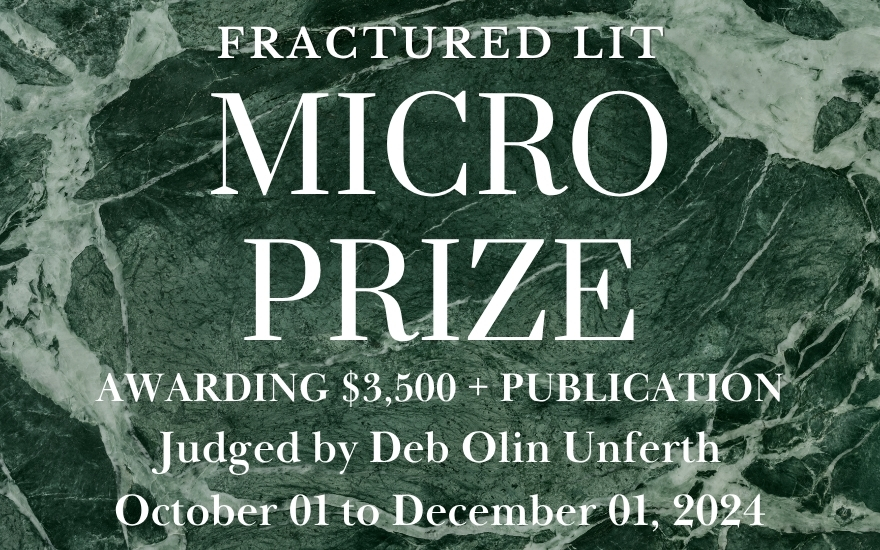

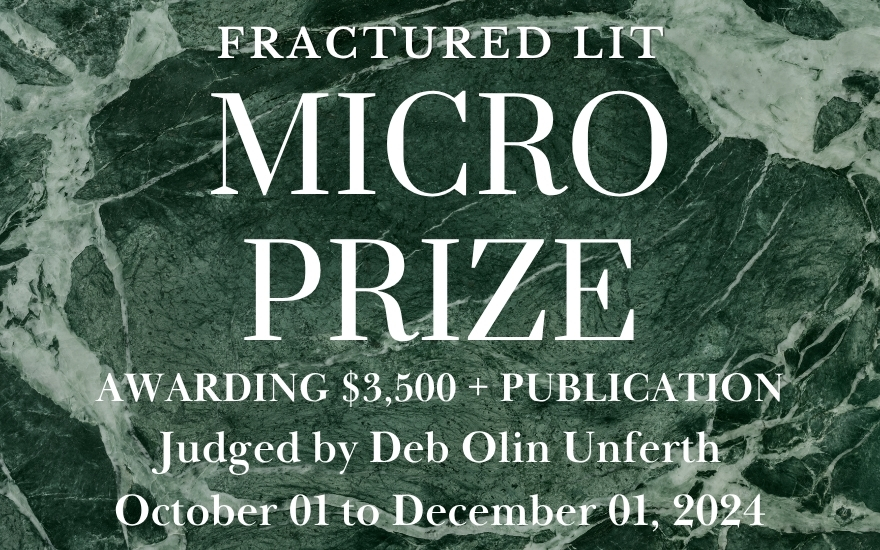

by Fractured Lit | Sep 17, 2024 | contests

judged by Deb Olin Unferth

October 01 to December 01, 2024 (Closed)

submit

This contest is now closed. Thank you to everyone who submitted and trusted us with your writing!

Fractured Lit has always been a place that celebrates the use of writing craft to tell small stories with big impacts. In the return of our Micro Prize, we want to honor stories of 400 words or fewer that tell a complete story and have us marveling at the depth of character and language. We’re looking for microfictions that demand more than one reading, invite us into their small containers, and awe us with the mysteries of being human.

We invite writers to submit to the Fractured Lit Micro Prize from October 01 to December 01.

We’re thrilled to partner with Guest Judge Deb Olin Unferth, who will choose three prize winners from a shortlist. We’re excited to offer the first-place winner of this prize $2,500 and publication, while the second- and third-place place winners will receive publication and $600 and $400, respectively. All entries will be considered for publication.

Want to know what our judge is hoping to read? Deb says,

“I like being surprised-by language, sound, a twist in expectation. Microfiction is about voice expression, about capturing one’s own sound and letting the reader hear it, see it, be moved by it, feel joined to it, feel separation when it’s over.”

Good luck and happy writing!

Deb Olin Unferth is the author of six books, including the novels Barn 8 and Vacation, the memoir Revolution, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, two story collections, and the graphic novel I, Parrot. Her fiction and essays have appeared in over fifty magazines and journals, including Harper’s Magazine, The New York Times, The Paris Review, Granta, and McSweeney’s. She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, three Pushcart Prizes, a Creative Capital Fellowship for Innovative Literature, and fellowships from the MacDowell, Yaddo, and Ucross residencies. She’s a professor at the University of Texas at Austin, where she teaches for the Michener Center and the New Writers Project, and she also directs the Pen City Writers, the prison creative writing program at a south Texas penitentiary. Originally from Chicago, she lives in Austin with the philosophy professor Matt Evans.

guidelines

- Your $20 reading fee allows up to three stories of 400 words or fewer each per entry-if submitting more than one microfiction, please put them all in a SINGLE document.

- We allow multiple submissions-each set of three microfictions requires a separate submission accompanied by a reading fee.

- Writers from historically marginalized groups will be able to submit for free until we reach our cap of 25 free submissions. No additional fee waivers will be granted.

- Please send microfiction only-400 word count maximum per story.

- We only consider unpublished work for contests-we do not review reprints, including self-published work (even on blogs and social media). Reprints will be automatically disqualified.

- Simultaneous submissions are okay-please notify us and withdraw your entry if you find another home for your writing.

- All entries will also be considered for publication in Fractured Lit.

- Double-space your submission and use Times New Roman 12 (or larger if needed).

- Please include a brief cover letter with your publication history (if applicable). In the cover letter, please include content warnings as well, to safeguard our reading staff.

- We only read work in English, though some code-switching/meshing is warmly welcomed.

- We do not read anonymous submissions. However, shortlisted stories are sent anonymously to the judge.

- Unless specifically requested, we do not accept AI-generated work. For this contest, AI-generated work will be automatically disqualified.

The deadline for entry is December 01, 2024. We will announce the shortlist within 12-14 weeks of the contest’s close. All writers will be notified when the results are final.

Some Submittable Hot Tips:

- Please be sure to whitelist/add this address to your contacts, so notifications do not get filtered as spam/junk: notifications@email.submittable.com.

- If you realize you sent the wrong version of your piece: It happens. Please DO NOT withdraw the piece and resubmit. Submittable collects a nonrefundable fee each time. Please DO message us from within the submission to request that we open the entry for editing, which will allow you to fix everything from typos in your cover letter to uploading a new draft. The only time we will not allow a change is if the piece is already under review by a reader.

OPTIONAL EDITORIAL FEEDBACK:

You may choose to receive editorial feedback on your piece. We will provide a two-page global letter discussing the strengths of the writing and the recommended focus for revision. Our aim is to make our comments actionable and encouraging. These letters are written by editors and staff readers of Fractured Lit. Should your story win, no feedback will be offered, and your fee will be refunded.

submit

by Danielle Levsky | Sep 16, 2024 | flash fiction

The autumn chill permeated Ruth’s wool coat as she hurried through the forest, dried leaves crunching underfoot. She clutched her satchel laden with contraband. If her parents found these candles, herbs, oils, and feathers plucked from her pillows, they’d demand answers she couldn’t yet give.

Soon the sheltering arms of the old willow appeared through the trees. Beneath its curtain of tendrils, Orli waited, tracing the perimeter with her feet under the waking moon. Her hair was wild in the wind, eyes bright with anticipation. “You came,” Orli whispered, taking Ruth’s cold hands in her warm grasp.

Ruth’s face flushed, as she always did at Orli’s touch. Her dreams these past months had been filled with images she didn’t dare examine by daylight—of clasping Orli’s slender hand, resting her head upon her shoulder, pressing her body close until all borders between them blurred.

Orli took Ruth’s satchel, withdrew the oil, candles, matches, and herbs. “Tonight, we complete the ritual of renewal,” she said. They entered the willow’s hallowed shelter, the green swaying gently in the breeze. As they stepped inside, the wind outside seemed to fade. Stillness. Ruth found anchorage in Orli’s dark eyes.

Reverently, Orli scraped arcane symbols on the ground, cast a circle of salt, and lit herbs that filled the grove with earthy incense. Ruth’s pulse quickened as Orli took her hands. Together, they chanted the prayer Orli had taught her: “Mother Moon, grant us wisdom so that we may shed false skins.”

As the chant slowed, their voices twined until Ruth could not tell where hers ended and Orli’s began. Ruth met Orli’s eyes, luminous pools in the candlelight. A bittersweet ache grew in her chest as she yearned for the impossible—to create life from Orli’s flesh, to mother children woven of only them. She wanted to lay bare the caterwauling of the moon above, to reshape the fabric of her world.

“Now, we consecrate,” Orli finally whispered. Ruth froze, then softened, then shivered as Orli traced oil down her arm, her breath catching at the nape of her neck.

Ruth’s desire overtuned. She returned each caress, skin prickling, praying the ancestors Orli invoked could not see into her thrumming heart. Orli traced Ruth’s hips nine times to unbind as Ruth stroked her shoulders seven times to sanctify.

Where you walk, I would walk, Ruth thought to herself, setting a new prayer, hoping the ancestors could hear. Your people will be my people, your home my home.

Their bodies spilled salt and nectar, with tongue and teeth they exhumed their ways. The trees creaked and groaned as they called out under the moon’s watchful eye. They became conduits for crones turned to ash, chanting to release their buried words. Their braided fingers intertwined at last in the dancing firelight. They kissed with wild abandon, removing shame and garments alike.

At dawn, the salt dissolved, and the wind stilled. The last herbs burned to embers. Orli leaned her forehead against Ruth’s, sweat trickling down. “The old selves are shed,” she whispered. “We can now live as we were meant to.”

They emerged naked in truth. Stepping into light, Ruth hid no more in shadow. Together, they walked and faced skyward.

by Tanya Nikiforova | Sep 12, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

“He’s bleeding out!” These words stampede through the air, disembodied from their owner. “Somebody help him!”

I stand on the museum steps. When the words reach me, I am unsteadied by their desperate velocity, and I wobble on the bottom step.

I hope they have reached ears besides my own, but the green lawn abutting the museum, usually speckled with undergrads, is empty. For reasons I can’t understand and will dissect later, I move toward the voice.

Around the corner of the museum entrance, I find a woman with her back to me, kneeling on the grass as she holds a phone in trembling hands and dials 911.

She sees me, and gasps.

“He’s bleeding out,” she says softly now. “Help him.”

In front of her, a man lies on a red blanket. His eyes are closed and his lips are slightly parted. I gawk, stupidly, letting seconds pass. Professor Liang’s words are in my head: Don’t just look, Kate, see.

No, it’s not a blanket he’s lying on.

He is lying in a pool of blood.

I note hues of cadmium, carmine, and amaranth. And the smell of earthy rot.

Across his neck, there are two short slits that just barely break the skin. But on the left side of his neck, where one usually goes to feel their pulse, there is a third puncture, this one cavernous and deep, and blood gurgles like a brook through this opening.

“Help him,” the woman whispers hoarsely.

I pat down my body, confirming that I have nothing to apply pressure with. I look at my hands. They handle cancerous turpentine, resins, and pigments all day, but the idea of using them to touch a stranger’s blood feels perilous.

I see two young women gathered, maybe ten feet away. “Can you give me a piece of clothing?” I ask. The one on the left looks disgusted, like I’m asking her to strip naked. The one on the right removes a flannel shirt tied around her waist and throws it to me.

I crumple it up and press it to the man’s neck. I hold pressure with the shirt, and blood starts to soak through. I press harder. When I look up to say thank you, they are gone.

“They’re asking if he has a pulse,” the woman calling 911 says.

Not being able to check his neck as I am practically choking him with the shirt, I feel along his left arm. I can’t find it at first by the wrist, but then there it is. A weak, thready thump beneath my thumb.

“Yes, I think so,” I yell back.

For the first time, I look at the man’s face. He is in his sixties or seventies, with a thin smear of gray, matted hair. He is cleanly shaven. He wears a short-sleeve khaki button-down shirt that is tucked into suit pants with freshly pressed creases. A sunken stomach bows beneath a fine leather belt. In the palm of his open hand lies a small kitchen knife, the kind you use to peel an apple, with an ochre wooden handle. While holding pressure with my right hand, I use my left hand to move the knife away and stick its sharp side down into the dirt.

“They said keep holding pressure,” the woman yells. “They’re on their way.” And then, “Hurry, please,” she pleads into the phone, and reminds them, “There’s a lot of blood here.” The man opens his eyes. “You’re hurting my neck,” he says, but doesn’t move to stop me.

He doesn’t reach for the knife. “Let me die,” he says.

“I can’t, I’m so sorry,” I tell him.

What am I sorry for? The pain I’m causing him? Or for keeping him alive?

And then he slips into unconsciousness again.

On the orders of my professor, I was here to walk through the Gauguin exhibit for inspiration. On her last feedback form, Professor Liang wrote, “Technically proficient. Completely uninspired.” Last week in class she temperamentally paced as we painted. When she stood behind me, she asked, “What are you trying to say here?” I just wanted to paint things perfectly and beautifully, but so far in my MFA, I have learned only that beauty is the opposite of art. “Nothing,” I told her, defiant. “I thought so,” she said, and walked away.

I resolve to paint him the way I found him.

Yet I fear that the stress of this moment will overwhelm me afterward. I will disremember every detail when I sit down to sketch, and without the details, I will fail.

I take the knife out of the ground and place it back in his hand. Still holding pressure on his neck, I take my phone out of my back pocket. I bring it to my face to unlock it.

The woman who called 911 is leaning against a tree, looking at the ground and rocking gently. By the low wail of the sirens, I can tell they are a few blocks away.

I remove the shirt from his neck carefully. The main wound is no longer bleeding. I bring my phone close to his neck. When I take the first picture, the camera app makes that automatic clicking sound.

The woman looks up, horrified. “What are you doing?” she asks. I don’t say anything. Instead I take a few steps back and take a photo of his face, and then of his body. I am now standing over him, capturing every angle.

“This is disgusting, YOU are disgusting,” she hisses at me.

“You wouldn’t even touch him. You waited for me to get here, just letting him bleed out,” I say calmly.

And then I hear her make a little “Ohhh” sound as she looks down.

He is bleeding again, and now, instead of a slow gurgle, the blood pulses out of his neck rhythmically. I keep snapping.

The sirens grow louder. There isn’t much time left.

Any second now, help will arrive.

by Chris Negron | Sep 9, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

We went to the museum, but we didn’t see anything good.

We sat on a long bench under the great T-Rex, frozen in midroar. Outside, your son wound his way through a fake rainforest, raised pathways running under and over each other. He had darted for the doors as soon as the tickets were paid for. Escaping.

“Go with him,” you told your husband.

The sun spiked its rays between the branches, every few minutes shining straight into our eyes. Every few minutes making us squint. Every few minutes causing us to raise our hands to block out the unwanted light as we lost sight of our families. My wife. Your husband. Your son.

“I can’t see him anymore,” you said.

We were surrounded by the past, but focused only on the future.

The adults laughed as your boy led them around in mad circles. They doubled over, out of breath. Even they, the healthy ones, couldn’t keep up with him. Or maybe they weren’t trying hard enough. Maybe they were letting him run, because, lately, it was all he seemed to want to do.

“They’ll be all right,” you said.

And I couldn’t tell if it was a question or not.

We came here to talk, but that turned out to be harder than expected.

The silence was much easier. It came naturally, carried aloft by the pain that enveloped us both, transmitted by senses dulled by pills and injections. I shrugged my shoulders and gripped my cane harder whenever I felt myself slipping. You shifted and twisted your hips every time your colostomy bag pinched your skin wrong.

Eventually, words came. Some anyway. College, stepmother, IRAs. Next husband, graduation, wedding. First girlfriend, prom. Remember to laugh, take care of my plants, don’t give away my comics.

Your son returned triumphant, pressing his breathless grin into the glass. Our spouses walking twenty feet behind him, talking with heads down, hands tucked deep into pockets, wrists clutched behind backs. They caught us watching and forced smiles onto their faces, sent too-enthusiastic waves our way.

We were the ones dying, but they were the ones it was killing.

“I’m going to miss it,” you said.

Slipping, slipping, slipping. I shrugged my shoulders. Gripped my cane harder. Straightened my posture.

The movie was about to start. Something about whales. In the museum we went to, different movies played every hour, but this particular one, only once per day. Your son loved whales, so we waved them all toward the theater.

“Try not to miss any of it,” you said.

“It only happens once,” you said.

They begged for us to join them, but we were too tired. Still, your son lingered. He leaned against your legs and glanced above you, straight at the giant teeth of the T-Rex. His curious eyes followed the old dinosaur’s bones from head to tail and back again.

He tore his gaze away from the old fossil, and his hands shot straight into the air. He winked his fingers open and shut. Obediently, your husband took one, my wife the other. They pulled him free from you.

And you did not reach out. And you did not try to force him to stay.

One last time, they—your husband, my wife—asked us to join them. They pointed up at the theater, not more than thirty feet away.

There’s even an elevator, they said.

We answered no. One last time.

Shoulders slumped, the two of them trudged up the ramp toward the double-doored entrance. Your son skipped faster and bobbed higher between them with each step closer. Closer to the whales and the ocean, to the deep blue, to the waiting nothingness.

Closer, closer, closer. Closer and farther at the same time.

Because we followed them, but only with our eyes.

by Danielle Mund | Sep 5, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

In the first month of the year after the holiday season she felt out of sorts (the season she got the diagnosis, the season the doctor gave her a referral to the Giant Hospital), Barbara bought things. She awoke every day with the phrase carpe diem on a looping conveyor belt in her mind, showered in frigid water as soon as it shot from the showerhead (to wait for it to turn hot was the difference between life and death), and dressed quickly and simply, for it was imperative she be at the Big Lots! when the doors opened at nine. Not getting coffee at Starbucks across the street, not parking in the parking lot, but actually standing at the door. If she wasn’t, she’d already lost out on the possibility of claiming the entirety of the day’s clearance rack, lost the day’s meaning. Once she was inside and had chosen the right shopping cart, she wheeled it directly to the farthest point in the store and began scavenging down the aisles. She loaded up on whatever was on sale: toothbrushes and bath bombs, Connect4 and Barbie dolls, bras too big and too small, leftover tinsel, a dog bed, a Discman with AM/FM radio, a swiveling office chair. She gathered them as a squirrel gathers acorns, each day collecting and organizing and storing, and just as a squirrel buries its treasure in the space between the heavens and the inferno, so Barbara rocked herself into a trancelike state between the aisles of her own meticulous making at home: Apparel, Holiday Decor, Office Supplies. Day after day she returned to the ever-changing display at the front of the store where a carousel of discounted items from electronics to baby bibs required a Tetris-like rearrangement of items in her cart. On the morning she cracked the puzzle without once having to take an item out before putting it back in again, she let out an audible “Amen,” and that afternoon arranged things at home without rocking. By then she was placing things not in the house but behind the garage, where there was a broken refrigerator she’d found by the side of the road. The fridge had compartments, and that was its point. Because she had a nagging feeling that lining things up along the backside of the garage could be considered the beginning stage of something unspeakable (she did not know what it was exactly, but it had to do with avalanches of tools, hidden insect nests, getting lost without anyone ever realizing), she told herself she was placing things outside only until her husband cleaned up his stuff, only until the exterminator came, just until she could find the stove, only putting things in a new place because it was more spacious, easier to see, only because things had a way of getting away from her in the house just when she needed them. The fridge reminded her that compartmentalizing was key, that preservation was crucial. Outside she didn’t have to worry about an avalanche when she rocked, outside she could stack things farther apart so they could breathe. Space was essential for creating new walls. Sometimes Big Lots! ran out of clearance items, and she’d have to go to Walmart or Target or search for some immaculate yard sale in another ramshackle town along the Hudson, pick up clues leading to the dump at the far end of town, find decaying toilet bowls or fish tanks. When that happened, she moved cautiously, limited only by her truck’s size, feeling, finally, the importance and care each item required of her, the mendable lawn mower, the patchable coveralls, the fractured mirror, the ripped duvet, the oozing boom boxes, the jigsaw that occupied her whole mind, body, and soul.

So that she never needed help, she kept a jack (or three, and a detachable folding hauling bed, ready whenever she needed it) in the back of the truck. She could lift a whole rusted-out car with two hands (slip the jack under its belly, forget the wheels, wheels fall off, wheels were to be organized separately anyway), and she hauled in dishwashers, boilers, and dryers. Sometimes, she would stand on top of the largest mound and stare out at the overwhelming security around her (she always tried to make eye contact with the landfill manager, a sign of impregnable mental control, nothing ever lost in her world), and then she would shuffle back between the heaps, letting the natural bulwarks guide her to the sagging truck. In the first month of the year after the holiday season she felt out of sorts, the season she got the diagnosis, the season the doctor gave her a referral to the Giant Hospital, a horrible season to exist, Barbara welcomed 4,798 treasures big and small onto her property. Sometimes, in the late afternoons, the terror would course through her bloodstream, form a new growth in her brain, shoot her in the eye with vivid visions of rectangular wooden boxes and yellow carnations and insect-filled dirt and the inevitability of what she’d already created for herself in this world, but all that disappeared when she was amongst her things.

by Zach Moser | Sep 3, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

In 2023, the island known in County Kerry as the Sleeping Giant, named for its resemblance to a man lying on his back, exhaled. Those first few people to see it were quick to dismiss the notion they must have seen mist rising or a flock of gulls. For, as they explained, they had seen the chest of the Giant sink, then rise. In only a few hours, the people of the Dingle Peninsula on the west coast of Ireland, just east of the island, had nearly all seen for themselves that the Sleeping Giant had indeed exhaled. And continued to do so throughout the day and into the evening.

When a length of brownstone that could only be an arm slowly inched into view on the westerly side of the island, even the oldest Dingle men in their drinks, whose brows were furrowed in a never-ending scowl of suspicion, suddenly raised the tips of their caps, eyes widening in deep alarm. The Sleeping Giant was breathing, and it was no longer sleeping.

Schoolchildren were rushed home, restaurants closed their doors and turned off their gas, the pubs stayed open, and the fire towers set up 24-hour watches with binoculars and floodlights aimed at the Sleeping Giant who inch by inch over the course of a week lifted a great earthen hand up above the curve of its belly. In the towns on the small peninsula, villagers rushed from house to house to trade news and misgivings. As they ran across thin cobblestone streets, their heads were tugged toward the island as if beckoned by the slowly rising rock.

When another brown tract of land rose from the sea on the easterly side of the island, and five hard fingers breached the turquoise surface of the sea, the wind picked up. The weather could change from one street to the next on a normal day in Dingle, but three weeks after the Sleeping Giant first exhaled, a cold wind began to pound steadily from the direction of the island.

Every day, the Giant rose farther out of the Atlantic, and every day, the gale winds blew fiercer. Shutters clapped, and handkerchiefs were ripped out of people’s pockets. Sheep, oblivious to the growing shadow in their farmers’ lives, were blown like white tumbleweeds across the pastures. One shrewd farmer tied bricks of peat to his herds’ hind legs. This worked for only a few hours before the animals decided their weights were tastier than the grass and ate away each other’s anchors. The farmer came out later that night to see his sheep pinned against his far gate, baa-ing indignantly.

After four weeks, the Sleeping Giant was sitting up, its head bowed to its chest as if still drowsy. Some on the peninsula fleetingly thought to call the taoiseach in Dublin but decided that as the problem was off their shores, it was theirs alone to endure.

The Iveragh Peninsula to the south thought the same. When a constable from a seaside town peered north one night and saw the Sleeping Giant bent over, twice as high as normal, he said to his wife, “They’ll be having trouble up around Dingle, I imagine.” The Irish government would not have been much help anyway. Irish Rugby was preparing for the quarterfinals of the World Cup, their eighth visit, and most folks had their focus invested on the pitch.

The villagers’ disquiet turned to dread when on the fifth week, the Sleeping Giant’s head turned toward them. Neighbors stopped visiting each other’s homes, the only gesture of community was blinking flashlights from slatted windows. Even the pubs were silent, drinks ordered with finger raises rather than words. There were no songs. The wind was too loud. And every night, the young children cowered together under the sound of gnashing and grinding as the Giant rose ever upward.

When the Sleeping Giant rose to its feet, bent in a squat, rain, hail, and wind smashed into the peninsula with hurricane force. Families moved beds into basements, preparing for when the Sleeping Giant finally stood. Generations of Dingle families looked out over the ocean to see their friendly island. Now, to find out it had been a monster in the mist, many were surprised to find strands of betrayal mingling with the nest of fear and worry cocooned in their chests.

Six weeks after the Sleeping Giant first exhaled, at midnight, the wind died. Families in their basements awoke, shocked by the sudden silence. Men and women in the pubs put their drinks down and looked over bent shoulders as moonlight peeked through the boarded-up windows and painted their faces. And then a mighty roar.

Cracking stones erupted, winds screamed over the island like banshees, and rain drummed angry as a military tattoo. Every light on the peninsula was extinguished and fathers and mothers held their children, and those in the pubs held their drinks and occasionally each other.

The next morning, to everyone’s shock, the sun rose. One brave child sprung from his bed and raced outside. His mother screamed after him but when she went out, she fell silent. Just as everyone did that morning. Fences were twisted into balls, windows were shattered, and fish lay all over the streets, some still flopping. But the damage was not total; only one man died. The farmer who had tied peat to his flock had tried the same trick with cement blocks only to receive a kick from a fed-up ewe right to his temple.

Out on the ocean, the Sleeping Giant was gone. The people smiled at each other, but only because they were supposed to, they had survived the danger after all. But in their hearts, something ached. There was a hole in their ocean where an island once stood. They cupped their eyes, searching for the monster who had made its home along the same blue-and-green coast that they themselves had loved so well.

by Sara McKinney | Aug 29, 2024 | Uncategorized

When the Children came back, they came back different. Dante had an arm that wasn’t his attached at the shoulder. You could tell because of how long it was, much longer than the other, and the fact that it was on backward. Rachel, who always talked so much before, couldn’t talk at all except to let out a little screaming laugh when you bumped into her, and Maggie, well, some sort of animal must have got at her because her face had chunks missing.

We didn’t quite know what to do with them, although of course the parents were happy. New toys were purchased, old bedroom furniture repainted in bright, smiling colors. They brought the Children’s clothes out of storage and washed them, so the Children didn’t have to keep wearing the suits and dresses (now quite musty and moldy in places) that they were buried in.

In school, the Children sat silently, stiffly, facing forward at their desks, unblinking. This was true even of Jimmy, who used to be such a clown, throwing pencils at the ceiling and performing acrobatic dismounts from the top of his desk, but now he never laughed or spoke except to say please and thank you in a voice that creaked like a door hinge left unoiled for a century. Their homeroom teacher confided in me one afternoon when we ran into each other in the hallway that she was leaving them alone more and more often, sneaking into the lounge or the bathroom to sip from a small glass bottle while the Children stared obediently at the chalkboard. When she came back, they were always exactly where she left them.

“It’s the stillness,” she said, her hand on my arm as if it were a banister on a staircase she couldn’t quite trust. “The perfect stillness, I can’t stand it. There’s something still dead about them. They’re alive, but not really. They don’t breathe, I’ve noticed.”

I frowned at this; the teacher was a downer and always had been. Everybody knew it. I rather liked the Children in their new state, even the ones who hadn’t come out totally intact but instead leaked juices onto the carpet or belched out centipedes and beetles. There was something lovely about their wanness, coldness, stiffness, how you could look out on the schoolyard and see them playing the way they played now, no running or jumping or screaming, only sitting in neat pewed rows while one of them lay on the ground, eyes closed as if sleeping and at peace. Their positioning was always expressive, finely articulated in the tilt of heads and necks, the way a doll’s might be. Death had fashioned them all into actors.

It was nice to think sometimes that in a kinder world my own son might have been among them, his own wanness, coldness, stiffness endearing him to the other Children. I imagined them passing the small swaddle of his body back and forth, incorporating it into their scenes of mourning, a younger sibling, a prop and a wonder. I imagined wiping the soil from his skin and teaching him to play like them, quietly laying him to rest, not in another coffin, but in the crib that stood, unused, in my attic. Now play dead, I would say, and he would die, temporarily and incompletely, his bright green eyes watching me from under the lids. But my son was not like the other Children; my son had been born dead. There was no life to return to his body, and so he stayed below.

“Well, it’s not their fault,” I sniffed. “We asked them to come back. And they’re a bit too young for labels.” This was true, although none of them would ever grow any older. Before she could respond, I headed back to the lounge, because I didn’t want to hear it. What right did she have to complain about them, anyway? Certainly, our jobs had become easier. The Children were, if nothing else, well-behaved, as sweet as any mother’s dream.

Recent Comments