by Miles Parnegg | Nov 19, 2024 | micro

They left the couch, a show about child prodigies gone insane in their twenties, and in her room he pulled loose her knotted drawstrings. Outside, snow. Frost clinging to power lines like cake piping, a blizzard fooling everyone and, for once, lingering. She breathed in and nodded, the hair under his palm short and prickly as iron shavings. Through the afternoon they touched each other, trading off—stopping now and then to make quesadillas, blush as they came out of the bathroom. He’d reach for Kleenex but she’d push up onto her knees and say, Let me, and bend her head to his abdomen, the way she did over a microscope in chem lab, curling her hair behind her ears, tucking the pendant on its chain into her shirt. Webs of ice spread from the corners of brittle windows, and the stuffed elephant on her bed—did he have a name?—was missing a marble eye, caught in a wink.

Wednesday came. Thursday. He drove down Edith with the heater on high, a beanie, a parka, ski mittens. His breath pluming in front of him as he waited for her to answer the door, the tongue of the lock licked slowly back in its bolt. They didn’t talk. They kissed and napped and felt their bare thighs pressed under sheets printed with royal corgis.

The last morning, as the thawing began, he hit black ice and floated into a ditch. He missed the telephone pole, and a neighbor in Carharts pulled him out with a cable and winch. He explained to her why he was late, pointing to the dented fender, the icy brush wedged in the radiator, the fan of mud up the left side—proof of gallantry—and they stood in the cold on her porch looking at the car, like it contained some answer, or a metaphor they’d draw on later. Inside’s heat moved out around their ankles and dissipated, and they stood on the frozen brick looking, afraid to move, as if they would dissolve if they drew their skin away and went back to what they could feel.

by Sarah Lynn Hurd | Nov 14, 2024 | flash fiction

I felt like television static that year—glossy-eyed afternoons at The Bitter End with a magazine straddling my lap, ears straining to dissect the waves: people chattering, milk steaming, door opening and closing—I was shimmery around the edges.

Most evenings, I drifted home through unexplored stretches of the city, somehow landing on the sidewalk outside my building. My roommate, Jolly, sat folded knees-to-chest, smoking a Montclair on the bottom step.

“Did you pass that accident?” She asked.

“Accident?”

“Don’t you usually take Jefferson? I read on Twitter that it was pretty gruesome.” I didn’t say anything. “Maybe accident’s the wrong word,” she said, stubbing out her cigarette. “They said the scene was active and graphic.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Apparently, someone had threatened to jump off the parking garage near the museum and then done it. Jolly talked about it for ten minutes—or maybe thirty.

She stared at me.

“Sorry, did you ask something?”

“You just don’t seem very present.”

“I don’t feel very present.”

“Maybe we should talk about something else,” she said.

I shrugged.

“You know Cora’s seeing a new girl?” She asked. “She’s always making this dumb face.” She raised her brows and pursed her lips.

“You don’t have to say that,” I said. “I’m honestly happy for Cora and her new girl.”

Cora and I were never a good match. We met when it was too hot out for logic or good sense. Humid twilights in August, sprawled on damp grass after the sprinklers ran in the public park, sucking on cherry pits and stained fingers. I’d trace along each bump of her knuckles, her hand in a loose fist on my stomach.

But all throughout winter, we were sullen, ladling our melancholy into each other until we both overflowed. Wine-tinged mouths dripping passive-aggressive remarks or nothing at all for days. It’s a wonder we made it six months each year, cyclically parting from March to July.

As the days grew long and sticky, we inevitably fell back together like mice into a bowl of oil, climbing atop each other to catch our breath. I don’t know if we kept the cycle up for the routine or because we couldn’t fully wash the oil off during our months apart. Our last split, Cora had told me, would be the final one.

“There’s nothing I can say that will make you feel better,” she said, boxes stacked in the hallway behind her. I wanted to ask, how about ‘never mind, I still love you?’ but her phone rang before I could open my mouth.

“This is Cora,” she answered, a plastic bag stuffed with dirty clothes and half-empty shampoo bottles digging into her soft inner elbow. She struggled to pull the apartment door open with her flexed foot. “I can talk—I was just wrapping something up,” she said into the phone.

By late September, she was with another, and I was taking a lot of long walks.

I’d been thinking about death that day when a stranger leapt from the parking garage near the museum, but I hadn’t been thinking about it like that. I’d been thinking about the first time you try to recall an inane detail about an ex and realize you can’t find it. What was her first dog’s name again? I had former lovers who could be dead by that metric—but like an oil stain, some people are impossible to completely wash away.

“Wanna grab something from Leo’s?” Jolly unraveled, standing.

“I’m not hungry,” I lied. “I’m gonna call it an early night.”

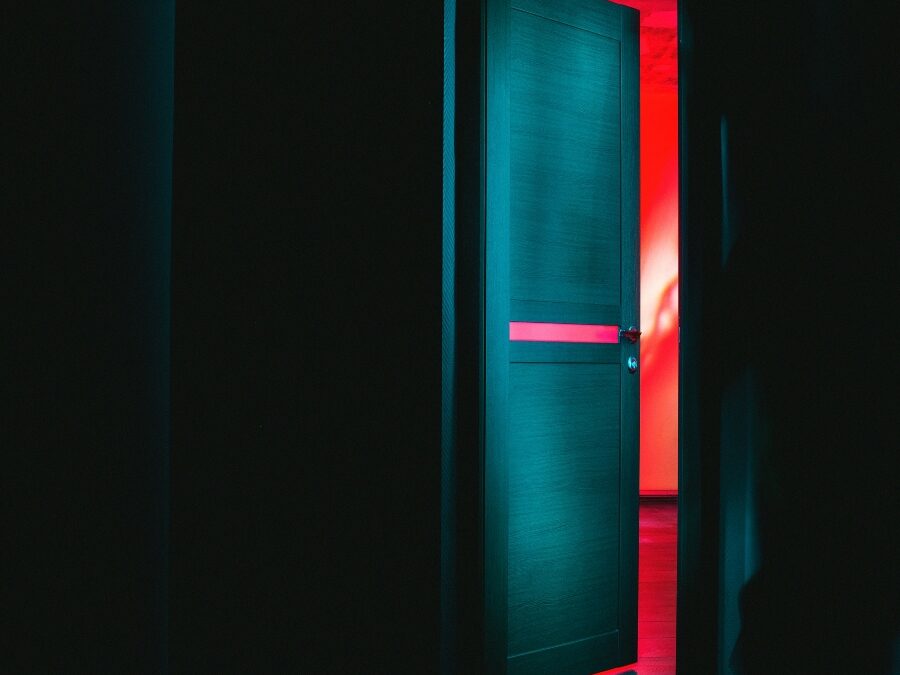

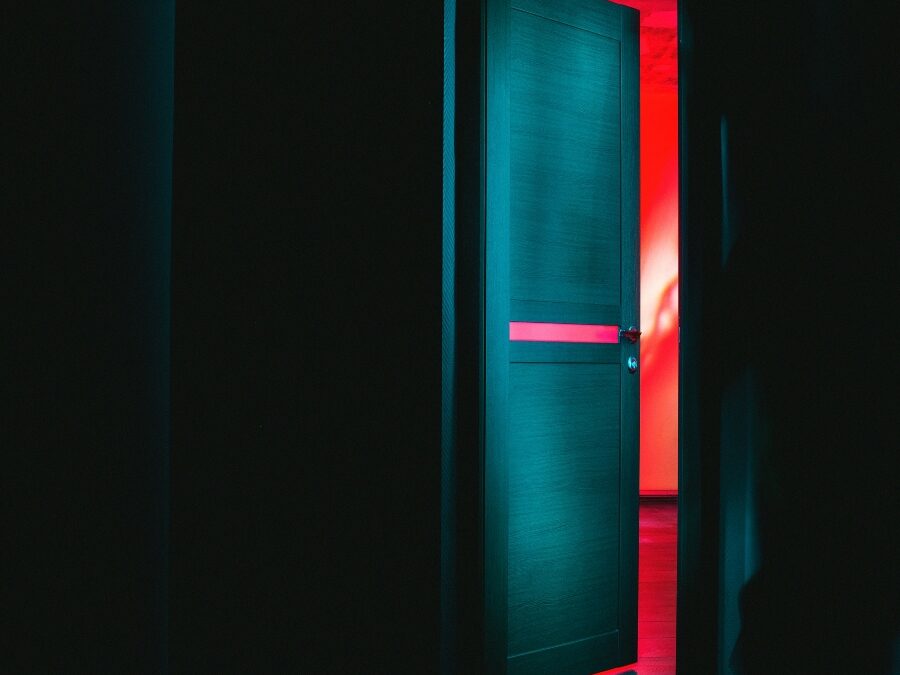

I climbed the three curving staircases to our attic apartment. With each floor, the stairwell grew darker, the air thicker. Even during the day, the hallway to our door felt like wading through black velvet, only the blue light of a phone screen to guide the way.

In my dimly lit kitchen, denouements swirled like fog, and I found myself rinsing lentils in a sieve over the sink. I used to sort the lentils while Cora peeled the garlic—I hated the paper-thin skin beneath my nails, perfumed oil seeping into my fingerprints. Even when we weren’t talking, she peeled the alliums. One night toward the end, we stood hip-to-hip in silence, Cora peeling, me dicing. She placed a naked yellow onion in my hand; I took it without a word. At some point, as I hacked into the celluloid-like rings, I realized she’d stopped moving.

“Do you need something else to do?” I asked without looking up.

Silence. I turned, and she stared straight ahead, eyes welling. “Cor, you can’t just be upset without telling me why.”

“Nothing,” she shook her head. “No, it’s just the onions,” she managed to choke on a laugh. I laughed with her, but I knew it wasn’t the onions. It was forgetting to return her texts when I went out with friends and lying about what I’d eaten all day. It was sneaking away to the bathroom after each meal and ignoring her for a week if she talked to other girls at the bar, even though I’d been the one to kiss someone else.

On my own, I overcooked the lentils—burnt yet soggy. Squatting on a stool beside the compost bin, I spooned them into my mouth anyway. My therapist said I should build a ritual around eating—set the table, use my favorite hand-thrown bowls, tuck my phone away—she said it would help me stay present, find my body’s cues.

But I didn’t want to feel my heart’s rapid jostling—a reminder that my body was soft, weak, and filled with blood—that it would burst on contact with pavement from a few stories up. I was tired of months seeping between my fingers as I lolled fully clothed atop the comforter for a time-lapse of seasons. Was it a kind of death? Those last few flickering scenes before sleep, like rainbow-gray waves collapsing across a television screen, sometimes felt like falling.

by Ciara Alfaro | Nov 11, 2024 | micro

after Meredith Martinez

My husband left me in February. He left with my love in his hands, and I walked to the pharmacy for a carton of eggs. The eggs were carried home in my dirty tote bag like a promise kept. I did not swing them, jerk them, or threaten to jostle them excessively. I walked past the K-Mart and the spinal specialist. The sky was pregnant gray, but passing the shops, all I could see was red. The thought of brittle shells crawled beneath the skin of my fingers. My hands felt stone cold then, the way a neck crack tastes. Once home, I placed the eggs in the fridge—cleared out a whole shelf for them. It’s not so hard, to make space for a fragile thing. All you have to do is open the cold, hard machine with an oath to move gently inside. That night, I could not sleep, for I could hear the phantom cracking of the eggs inside my ears. I felt them between my teeth. What happens to sadness grinded in the mouth? It never speaks. I hurried through the bodies that furniture makes in the dark, my stomach and pelvis slick with sweat. I kneeled in front of the refrigerator’s chill. Gently, I opened the carton of eggs. I counted them. I pressed my finger to their heads, sighing when I hit a special rocked groove. I rolled them around in my palm until I felt their insides move back. This was how I named them, how I loved them, how I vowed never to leave them first or even second. I bought ninety more cartons until April came. I broke teeth. I saw red. I had a man—a body in my arms—and then, I did not. What happens to an egg that is never eaten? It dries out. It becomes unusable. Spoiled, miscarried. When I say grief, this is what I mean.

by Nora Nadjarian | Nov 4, 2024 | micro

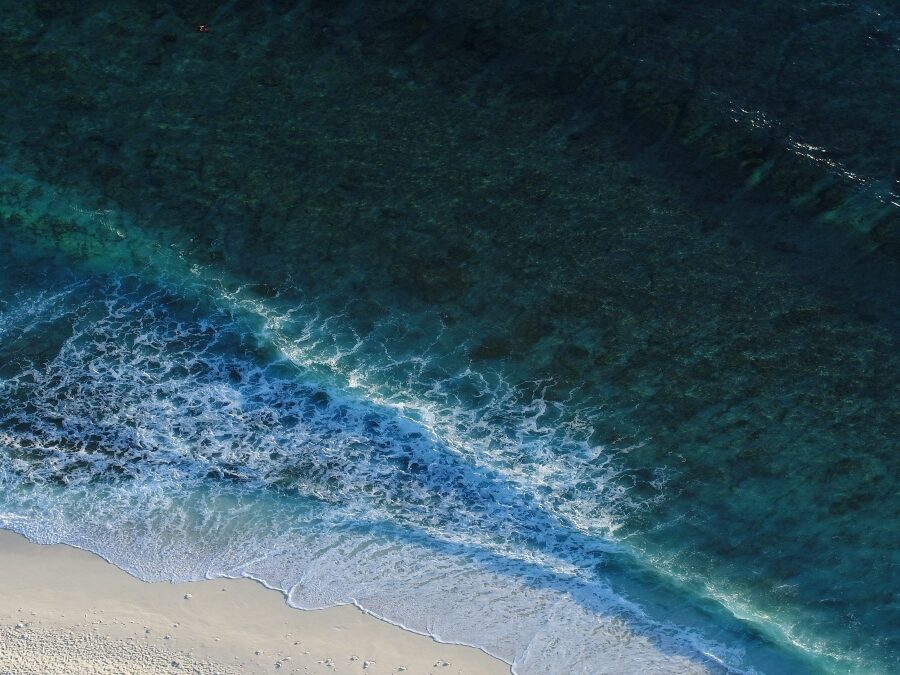

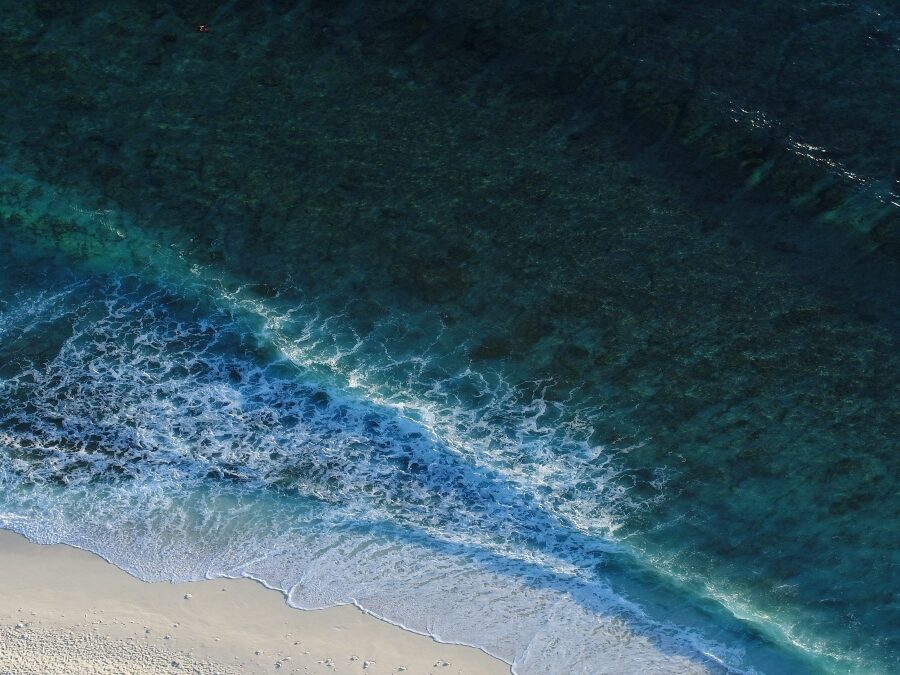

The moonlight-sequinned sea says There’s something I want to tell you. I walk on, pretending not to hear, fling a pebble at her face, then another, as far as they’ll go. The sea says, Listen to me, please. I want to tell her, Shut your waves up, shut your waves up and leave me alone; I just came here to light a cigarette and moon-breathe, not to talk about the past.

Sunburned tourists sit on van Gogh chairs, rest their elbows on checked tablecloths. I almost choke on the ebb of my memories and their flow. The sea says I didn’t mean it; the sea says I’m sorry, repeatedly.

A-long-time-ago returns, not as the calm moon but as a fierce sun, the sequins now on fire, the skin-peeled, salt-stung, sunscreen-polished tourists on their sunbeds, eyes shut under their umbrellas. Nobody saw anything. Not a single person noticed anything wrong with the world here on the spot where two girls stood. Two best friends dressed in matching bikinis, with matching ponytails and chipped nail-varnish toes, wade in, giggling. There’s a whole sea we can hide in, and the sea asks, Where are your parents? And the sea asks Where? The sea asks are? The sea asks your –

by Yejun Chun | Oct 31, 2024 | micro

My lover says that they’ll give me 380 words before saying goodbye forever, and it’s

380 words because she’s going to be dragged back North across the border and I’ll have to be

separated to the South;

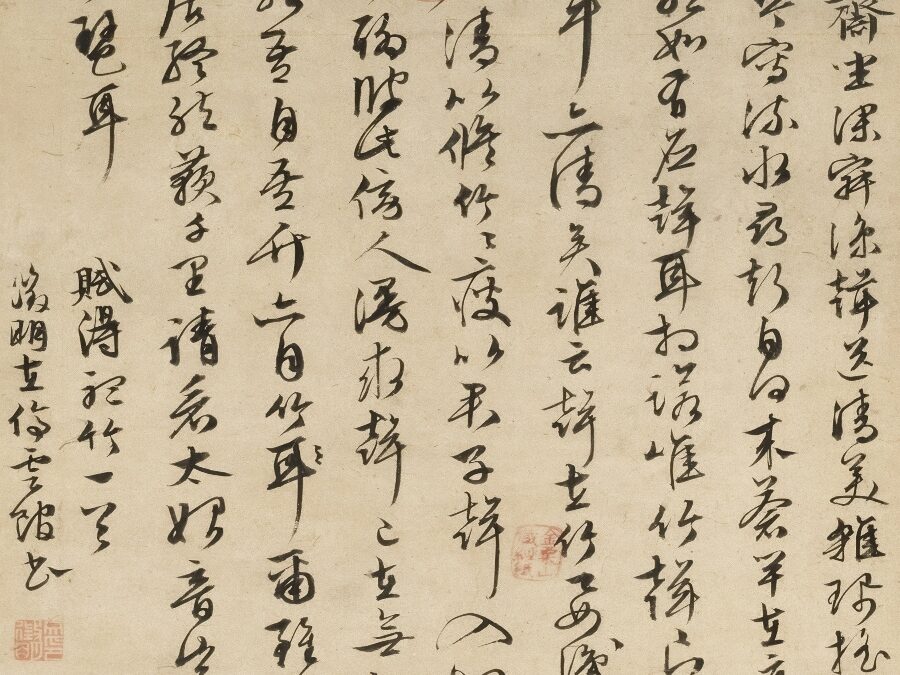

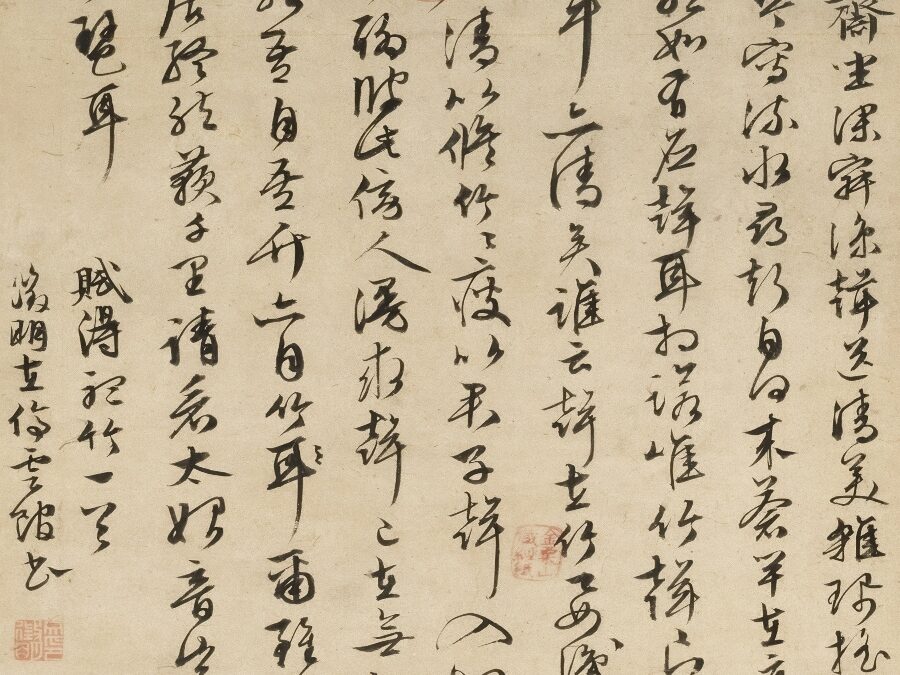

she checks her watch and tells me that I have 333 words left, so I grab a white brush

and dip it into ink, and I slowly write in traditional Chinese letters a poem from a Korean scholar

whom she likes very much, who wrote the poem during the colonial period, on her linen shirt

and then tell her of the time she was with me

when my uncle died and when he died, he died with a bullet to his innocent head

because he was wearing the color blood red which is the color of our hearts when we touched

each other’s skin, when we still had the passion and strength and courage to tell jokes to each

other.

We once went on a trip to see fields of rice and barley and we danced in the yellow

fields and it felt like a prayer, a message somewhat divine we were sending to the universe

through our bodily movements in the midst of that rainstorm and our recreation of our long-

lost childhood during which we never once saw the tip of a black gun.

I love you not only because of the small moments we spent together but also because

of the moments we didn’t spend with each other. The stars at night have never been so

bright to me, and the sound of pansori has never felt so sweet to my ears yet teary to my eyes.

Time can move so silently with you.

I have only 93 words now. Such a short time to do anything. It’s almost time to go.

She cries out as if words could last longer than a word count. Here’s an image:

Blue Han river flowing and carrying us on a wooden boat. Clear sky above us, and we

are holding hands: immortal in the moment.

Before she disappears and crosses the border, I kiss her lips, knowing that I have just

drank rice juice with her an hour ago, so she’ll think of my timeless love for her whenever she

drinks her favorite drink.

by Fractured Lit | Oct 29, 2024 | news

Congratulations to our grand prize winner: You Go Home by Steven Sherrill! We can’t wait to get your chapbook into the hands of our readers! Congrats to everyone on the shortlist! We know these chapbooks will find excellent homes in the future!

- Fish Eyes by Tala Ali

- My Years of Blue Violence by Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi

- Everything Bites by Elissa Field

- Consider the Grease Traps by James R. Gapinski

- Little Knives by Candace Hartsuyker

- Hurt Me by Sara Hills

- Fighting my enemies in the Applebee’s parking lot by Pat Jameson

- Roll and Curl by Ingrid Jendrzejewski

- Like Oil and Water by Melissa Llanes Brownlee

- All the Small Things by Bill Merklee

- Butterscotch Yellow, short fictions by Mamie Willoughby Pound

- Meanwhile, In the Hungry Dark by Mary Rohrer-Dann

- You Go Home by Steven Sherrill

- Kaleidoscope by Andrew Stancek

- Jazz Picnic: Very Short Stories by Dean Marshall Tuck

by Brad Barkley | Oct 28, 2024 | micro

After cake and ice cream, the guests, in their painted smiles and polka dot attire, settle in to watch the man they’ve hired to entertain them. An actuary analyst! So much better, already, than last year’s accountant or the year-before-that’s linguistics scholar. In his narrow dark tie and shirt sleeves, he opens his briefcase of tricks, produces an over-large ledger sheet and pencil, and, while the clowns watch open-mouthed, calculates a number of profitable, competitive insurance premium levels while determining the amount of cash reserves needed to assure payment of benefits and then— before they can even catch their breath—withdraws a dozen manila envelopes and reviews employee claims activity to see if premiums are adequate to cover losses. Hurrah! They laugh when he extracts a large seltzer bottle, lifts it high, and uses it to water down his scotch because he explains, Jill thinks he is drinking a little too much lately, though he can quit anytime he wants, and with a flourish, he sets up a cardboard bar and sits at it and lights a cigarette and runs his hands through his hair, opens his wallet to a picture of Jill, who (surprise!) left him last week, the kids, still in their braces, and while his magic In-Box slowly fills itself and after he breaks five pencils with one hand, out come the skinny balloons which he deftly twists into a variety of shapes, including the 5-alpha reductase enzyme that is causing both his baldness and that little twinge in his prostate, and the Q-shaped ucler growing in his duodenum. He leaves one balloon uninflated but won’t talk about it. The clowns are not, he tells them, his fucking therapist, and he never liked them anyway. The clowns cheer and laugh; this is so much better than anything, despite the bite of pathos they feel as the man cries now, sobbing into his open palms, and the clowns all know, know in their hearts, that this funny, sad man is really laughing on the inside.

***Originally published in Hotel Amerika.

by Aimee Parkison | Oct 24, 2024 | micro

Crypt 1: Broomstick Skirts

In robes of shell pink sunset over woodland hills, girls float the river to dance on hollow logs. Their gossamer gowns, devoured by fungus, release spores in the wind. In broomstick skirts, my sisters float skyward with petals on water. Soft as fleece, the faces our mother wears, one of them mine, smile as she walks away, strung out, outraged by a summer meadow at sunrise. The sunset bounces off her studio walls as she paints shadows.

Crypt 2: Shadow Painter and Man of Wood

In her shadow paintings, a man of wood dives into the ditch. Faceless in the trees, he rises to devour pears ripening in the moths of autumn, as delicate as hummingbirds, courting death in fire glowing like morning. A corpse acts with repose, cradling an unborn in a blanket as velvety as rabbit skin under a veil of silver stars.

Crypt 3: River Crows

Taunting the shadow painter with gray flowers, my sisters haunt gregarious crows purplish in strong sunlight, their woodland nest, a bowl of sticks in trees. Awakened, these intelligent ebony-hued large birds caw-cah-kahr the devious route that cuts through a muddy river slipping through a song as rhythmic as time.

Crypt 4: Women of Vines

A month, a year, a lifetime out of its depth takes hold like a drug. Whispers descend like the river luminous yet rooted to the earth. Women, many women, and girls wear faces like knives sheathed in dark vine. Girls ebb from communal dwellings where their mothers have no names but evening.

Crypt 5: Deadwood Rain

Like rain into deadwood, insects vibrate into hollows of the willows. Wood ants and roaches walk the trail like an old man’s necktie, where I linger in shadow painting, longing to become a shade like her. Leaning among the rocks of the morning, I encounter the monstrous blacksnake oozing digested blood, raising his head. My dancing tongue glitters with scales over his body.

Crypt 6: Fungus

Childhood memories fall like shawls over tabletops to disintegrate with visions leaching into damp soil where fungi grow.

Crypt 7: Anthropomorphic Girls

On my bedroom walls, the shadow painter paints a woodland world of wonder where girls like me become mushrooms and mushrooms become girls. She populates my room with the Questionable Stropharia, the Hooded Helevella, and the Capped Amanita. They skip with the Rose Coral and the Purple Laccaria toward the Prince and the Man-on-Horseback. Anthropomorphic, they linger happily under the trees with Wooly Chanterelles.

Crypt 8: Those Who Drink from the Death Cap

The mushroom girls pet a giant white human skull in the dark of the wood’s shallows. A giant Puffball. Is it good to eat? The girls begin kicking it like a soccer ball. Its spores mist the woodland painting toward the Death Cup, the Destroying Angel, fetid as forgotten dreams in the gills that sweat onto an Anise-Scented Clitocybe, laughing in a girlish manner.

Crypt 9: Gnomelike Foragers

At night, the shadow painter creates murals of fungal joy on my walls. In patterns of spore prints, she paints my sisters walking under the oaks holding large mushrooms as shaggy parasols. Lepiota rachodes. Gnomelike, sauntering behind the girls, foragers wear mushroom caps on their heads.

Crypt 10: A Dead Man’s Foot and a Dead Man’s Hand

Along a roadside near the trees where girls walk, a Dead Man’s Foot leads to a Shaggy Man. A Dead Man’s Hand emerges from the sand. By the light of dawn, I wonder if the shadow painter is warning me of death, then I realize all these dead parts are named after fungi that grow in the wild.

Crypt 11: Lithographs

Shadow paintings spread like lithographs on my bedroom walls where the radiance of water disappears around a big fir tree on the hill with the crudeness of realism and the graveness of graves.

Crypt 12: The Bone Princess

Shadow paintings smudge: shaded drawings scratched into caves. In my little room of morbid curiosity, the shadow painter confronts her captor. Her kidnapper puts her on display, exhibited, posed like a bone princess on a stone throne bearing no name. As if what happened to us was midsummer madness, we vanish without a trace.

Crypt 13: Nightmare Child

I was a child of thirteen when the shadow painter painted the bone princess at night on my bedroom walls. Night after night, she labored on a portrait of the bone princess. I sat up in my bed, watching in silent wonder, not daring to interrupt her.

My father assured me it was only a dream. A nightmare.

Crypt 14: The Unspoken

At night when the shadow painter visited, I wanted her to speak to me. I wanted to speak to her. She was always completely silent, afraid of light and sound. Shy. Being a shadow, a shy shade, she worked in silence and spoke through shadows. In her paintings, the House of Fire in the woods became a cottage of unspoken words where the lights turned off and on, producing a masterpiece of whispers painted on the walls. Unspoken: Mother. Daughter. Trees. Mausoleum of Gloaming.

Crypt 15: Evergreen Night

Staring into the mural, I found the nightly mystery of the shadow painter’s velvety chalk marks. The abstract patterns of the shadows beneath the trees seemed like witches flying above creatures, half human, half animal. They rise in graduations of tones of the evergreen night.

Crypt 16: Ebony Abstractions

She doesn’t try to duplicate the night woods but its moods and abstractions, communicating like children of the wind opening leaves as the maples quake and shiver out the fragrance of the trees after rain.

Crypt 17: The Moons of Her Eyes

Tonight, the moons of her eyes become a part of me.

I want to tell her that I missed her, but she’s shy. More than anything, I want her to stay because I suspect she’s my biological mother. Sarah Janowitz, the painter. Or rather she was the spirit of my mother. In particular, she was the shade of Sarah Janowitz, who had been a painter in life before she died in the woods.

Crypt 18: The Shade

As a shade, she had become one with her art. If I had not known her in life, I would have the privilege of knowing her in death, since she came to me at night. In her paintings, she spoke, showing me visions.

Crypt 19: The Slippage

Like all art, her shadow paintings were open to interpretation, and I often misinterpreted what she was trying to tell me about what happened in the woods, the way her body became an ecosystem all its own. In dying she fed many lives through the slippage of epidermis, putrid gas collecting in her distended abdomen, purging bloodstained fluid from her orifices. Exposed to animals and air, she was reduced to bone in ten days.

Crypt 20: The Body House

Her body housed insects. House flies entered her mouth, nose, anus, and eyes. Flesh flies gave birth to maggots that fed the blowflies. Maggots migrated in masses. Hide beetles, carcass beetles, and ham beetles arrived as her bloated body collapsed in the dirt of the mossy stones above the drop-off.

Crypt 21: Coffin Flies

Consuming maggots, large-jaw beetles tore open the pupal cases of flies inside her as she sat on a stone throne. The beetles carried mites that devoured the eggs of flies.

My putrefying mother decayed as her odor invited cheese flies. Wasps flew out of her mouth before coffin flies and beetles cleaned her skeleton, making her into a bone princess as moths came to devour her hair and clothing in a mausoleum of gloaming.

Crypt 22: The Old Mural

Light hides the mural from me. In every room, the shadow mural connects the walls in a silhouette, life-sized, incorporating the girls in the woods. It was always there in the background to befriend me when I was young. I often wondered who painted it and why. Every time I asked my mother, she told me there was never any mural in the house.

Crypt 23: Love

I wondered why others couldn’t see what I could see.

It was plain to me that I loved the shadow painter.

I love you, shadow painter.

I miss you, shadow painter.

Come back to me, shadow painter.

Crypt 24: Erasure

When I find her in the woods, the perfect skeleton scares me because I’m seeing someone who isn’t supposed to be there. Once again, the bone princess sits before my eyes. She’s in the woods on her throne of stone in the mausoleum of gloaming. She’s in the shadow paintings on my walls when I wake at night. Tonight, when the shadow painter arrives, I’m trying to stay awake long enough to watch her finish, since her paintings will be erased by the light of dawn.

by Evander Lang | Oct 23, 2024 | news

I’ve been a reader with Fractured since January 2024, and in that time, I’ve read hundreds of submissions. I’ve found that I end up passing on pieces for many of the same reasons over and over, and I’ve improved my own work by writing these reasons out for myself in detail, explaining to myself what isn’t working, how to identify the problem, and how to begin fixing it. In this piece, I will go through five of the most common issues that keep me from saying yes to a submission. If you’re a Fractured submitter or might want to become one in the future (and you should! The water’s warm!), I hope this list provides insight into what we’re looking at as we read and might give you some leads for possible revisions to your work.

Of course, every item on this list won’t apply to every kind of story. Many pieces we receive clearly signal that they’re trying to do something that goes against one or more of the ideas below, and our intention as readers is always to read each piece on its own terms. These are simply the most common issues I come across. If you read these and think, “That one doesn’t apply to what I’m trying to do,” you may very well be right, and you should trust your own vision. I’m trying to propose questions you can ask yourself about your work, not conclusions you must reach.

###

The Characters Don’t Feel Lived-In

One of the most common notes I make when passing on a piece is that the characters don’t feel “lived-in,” and one of the most common when saying yes is that they do. This can be a difficult term to pin down precisely, but I want to dig into a few of the reasons a character can feel lived-in or not.

Often, characters seem flat or underdeveloped because the reader has a sense of their being purpose-built: they are there in the story so that the plot can happen, or so that the author’s message can be communicated. Of course, every character is in the story because the author put them there – Isle McElroy once tweeted that “writing a novel is mostly being a middle manager for a bunch of little freaks you made up” – but the best writing gives its characters the quality of independent life, of possessing their own volition; the best characters seem as if they have collaborated with the author on the terms of their creation.

What does this look like in practice? A few examples of what an underdeveloped or not-sufficiently-lived-in character can look like:

- The only trait the character seems to possess is the one that relates to the current story: for instance, a story about Max’s battle with drug addiction in which Max’s only character trait is that he’s a drug addict.

- There’s a boilerplate quality to their dialogue or internal monologue as if their words/thoughts could be lifted and transferred to any character in any similar story: the character does not seem like Natalie, who’s falling out of love with her husband, but rather like Woman Falling Out of Love With Her Husband. That is to say, the character behaves as if they were an example of a type, not an individual. The reader might think, “I’ve heard almost that exact line in other stories.”

- They live their life as if it started when the story began as if they have no history: Max thinks about his drug addiction as if he only just started thinking about it, not as if he has lived with it for years, thought about it from many different angles, and has watched it inflect his experiences, relationships, and memories.

- Their actions seem imposed on them, unmotivated: sometimes this is because the action is at odds with what we know about them as a person, and sometimes it’s because we don’t know enough about them as a person to be able even to assess whether it’s at odds or not.

The common thread connecting these examples is a want for specificity. A lived-in character feels as if they had a real life before this story started and will continue to have one once it’s over; they have the idiosyncrasies and internal tensions of a real person. Natalie’s parents have been married for sixty years, and her brother’s been divorced twice by 27, and out of something like competitiveness, she insists to herself that she’s as in love with her husband as ever. Max has gotten clean in fits and starts, but the housing discrimination he faces as a formerly incarcerated person perpetually pushes him towards relapse, so that he has slowly become embittered toward the very prospect of quitting. Each has their own particular patterns of speech and thought, their own desires and fears, and their own sense of their place in the context in which they live.

If you’re unsure whether your character feels lived-in or not, try to write a few scenes with them that have nothing to do with the current story and may have nothing to do with any story: shadow them at work, listen to them talk on a first date, accompany them to a doctor’s appointment. I’m phrasing those ideas passively for a reason: release the character from having to perform in any particular narrative and let them come to you, let details adhere to them, and let them surprise you.

###

The Premise Never Develops

Imagine a flash piece that goes like this:

Beginning: the narrator tells us that she’s the night clerk at a hotel in the middle of the Sahara Desert. The desert is vast and unforgiving, and the hotel gets very few customers.

Middle: she describes what life is like at the desert hotel: the cleaning crew wage an eternal war against sand; fennec foxes are always getting into the dumpster and eating bagels from the continental breakfast.

End: she describes the intense quiet of her night shifts: she’s often there by herself, and there’s no sound but the wind against the windows, so she likes to watch movies from the hotel’s small stash of VHS tapes.

This is a kind of piece I encounter a lot: it establishes an intriguing premise but then stays parked there with the premise, adding more and more detail, but is unable to create forward movement in the story. The writer has created a hotel and put a person inside it, and I’m waiting to see what that person does. I learn what she does habitually, I learn about the static conditions and routine events of her life, but as I’m sitting there watching her, ready to learn what she’s doing now, at the time of this story, she isn’t moving yet. You’re giving me more detail about the premise – night clerk at desert hotel – but not moving beyond it, not setting anything in motion.

This problem can arise in many different kinds of pieces and can happen much more subtly than in this example. Sometimes, the piece moves backward to explain how we got to the present set of conditions; sometimes, the piece delves deeply into a character’s interiority, showing us how the character feels about the premise. These can enrich our understanding of character and situation, but they are not the same as narrative progress: we are still at the same place we started.

If you’re unsure if your piece develops its premise, look it over and ask yourself: what is different about the characters or the situation at the end of the piece compared to the beginning? What changed?

This problem can also occur by degrees; I’ve read several pieces that spend the first two pages of a three-page piece elaborating on their premise but not moving beyond it, only to hurry through a full beginning-middle-end story in the last page. The effect is that the first two pages feel unfocused, and the last one feels rushed and underdeveloped, since it was trying to do in one page the work of three.

As a reader for a flash fiction magazine, I get a lot of pieces that make me think the writer primarily reads novels instead of shorter forms and might “think in novels,” so to speak, instead of in flash. This is nowhere more apparent than in pacing; novels are very forgiving of excess, and flash fiction isn’t at all. If you’re having trouble deciding if you’re spending too long ‘setting up’ the action of your story, an exercise I find helpful is to imagine the piece scaled up to the size of a novel. Maybe spending one page out of three on setup doesn’t seem so long, but would you read a 300-page novel in which the action properly starts on page 100?

If you have a piece you feel is too rich in expositional detail, look it over and try to determine which details the reader has to know just to understand the story at all, and start by including only those. From there you might add in details you think meaningfully inflect the story, even if they’re not strictly essential. Be wary of falling in love with your premise, with the look of the stage before the play begins; however, pretty the set, we’re there to see what happens on it.

###

The Piece Lacks Focus

Your friend is telling you a story. She begins by saying, “So, I was on the subway heading to work, and there was this guy with a guitar,” and you think: this story is about a subway busker my friend saw. But during his song, your friend says, she saw someone else in the subway car wearing a jacket sort of like the one Ryan Gosling wears in Drive, and it made her think of her ex, who she saw Drive with, and how he wanted to get a jacket just like that afterwards, and she had to talk him out of it; after she got off the subway – this is back in the story’s present-time now – she saw a driverless car love-tap a bicyclist and speed off after, and she thought, what a world, they’re trained to do hit-and-runs now.

What was her story about? Why did she want to tell it to you? It doesn’t seem to be about the busker, but she started it there. It could be about the jacket and the ex, but you wouldn’t need to mention the busker to tell that part. Maybe it’s about driverless cars or the dangers of unregulated technology, but in that case, she could have left the subway out entirely. I decline a lot of pieces as a reader because they’re what I call unfocused: they touch on many things but seem to have no clear through-line; they include many different scenes or details but in a way that suggests the writer didn’t know which ones were important and which weren’t; they begin by establishing one point of tension and end by resolving another. I’m left unsure what it all added up to as if I just perused the component parts of many different stories but didn’t experience any of them in full.

From my experience and speaking with other writers, I sense that this happens when a writer isn’t totally sure themselves what the ‘core’ of their story is. If you know that you’re telling a story about a driverless car hitting a cyclist, it likely won’t even occur to you to mention the subway busker. If you know that you’re telling a story about how someone’s jacket sent you down memory lane, your imagination won’t even leave the subway car. Sureness of vision will indicate not only what to include but also the much greater number of things it would be better to leave out.

If you think this describes your piece, go through it and locate the parts of the piece you feel best about, the parts that excite you and feel essential to your vision. These can be anywhere in the story, and they can be anything: a character, a relationship, an image, a particular quality of the prose (be careful with this last one; the quality should be something more than just that you think it’s pretty). Maybe your beginning feels right, but after that, the story seems to wander. Maybe your ending feels perfect but doesn’t correspond to the story leading up to it. Maybe there’s just a single moment in the middle where it feels like your intentions and desires as a writer become legible to you, and everything else around it was just so you could get to that moment. Whatever it is, try to think concretely about what it is that makes that part of the piece feel so essential, so ‘right.’ You have a fixed point in the sky now, something you can use to navigate: write another draft knowing that you want to keep that moment more or less as it is, and begin thinking about the things that would logically precede or follow from such a moment. You might find another moment that feels consonant with the first; now, you have two points in the sky. You are locating the core of your story, the really indispensable thing at the center of it, and you can gradually build around it until the entire story seems to reflect this indispensable thing, and feels not only right but inevitable: these scenes could only play out in this way, this ending and no other could round the story off, the piece could be no other way but how you have at last discovered it to be.

###

The Theme is Presented Heavy-Handedly

“What is your story about?”

If you’ve ever been asked this question, you might have felt tempted to give two answers, not one: it’s about a hurricane in New Orleans, but really, it’s about generational trauma; it’s about a murder at a ski resort, but really it’s about capitalism. The first is the plot, the second the theme, and to say that a piece feels heavy-handed is mostly to say that the theme is overwhelming or crowding out the plot; the story has begun to feel less like a story and more like an essay or a treatise.

As a reader, I’m looking for some combination of fully realized characters, an engaging story, and a nuanced exploration of a richly depicted world or situation. A story begins to feel heavy-handed when its plot, characters, dialogue, and so on seem like they’re intended only to convey us directly to the author’s intended meaning; the experience of reading the piece is depleted, because there seems to be nothing to experience but its message.

This can take many forms, but here are a few of the telltale signs I often see:

- The piece depicts its tension or its characters in black-and-white, good-and-evil terms. If there are contrasting points of view in the story, only one is actually presented, or the opposing viewpoint is presented only very weakly so that it can be defeated. There’s some overlap here with the section about lived-in characters; characters without nuance never feel real.

- Characters or the narrator speak the message of the piece: they issue proclamations about the story and its meaning that nothing in the piece resists or complicates.

- The language of the piece is abstract and conceptual – truth, freedom, justice, trauma, etc. – rather than particular or specific. Emotions are invoked by name rather than depicted.

- The resolution of the piece is often unusually neat, to prevent a reader from interpreting it in any way but the intended one.

In my experience, this kind of oversimplicity often comes from a lack of confidence on the writer’s part – confidence in what their story is about or confidence in their ability to convey it. In my own writing, I tend to find that my first drafts are very heavy-handed: the characters are two-dimensional and constantly speak the subtext of the story, and the plot telegraphs its ending right from the beginning. I’m not sure what the story is yet, and I can only paint in the broad strokes of its shape. For me, confidence comes with revision. I’ve figured out what I’m writing about – in both senses – and I can find more subtle and specific ways to express it. For instance, you are reading the seventh or eighth version of this paragraph.

If you want to revise with an eye towards combating heavy-handedness and making your story’s theme flow more organically from its characters and plot, try this: write down as many words as you can think of that represent the theme or themes of your piece, then write a fresh draft of the story, in which you are not allowed to use any of those words. What does your grieving character do? What does the loss of freedom look like, scaled down to a public park in Sacramento on a sunny Tuesday morning? What is the meaning of justice in the fourteenth row of a Chicago Bulls game, or a DMV, or a Shake Shack?

The stories we keep coming back to – the Shakespeares and the Austens of history – continue to call us back because we never seem to have quite wrung all the meaning from them. Different people can find different things in them, and the same person might even find different meanings over time. What compels me more than anything else as a reader is basically this: that the piece has life in it, that I am not just reading it but conversing with it.

###

The Prose Gets in the Way of the Story

There’s no one particular prose style that every writer should be trying to use; each story will have its own voice. Generally, what I’m looking for in a Fractured submission is simply prose that feels “right” for the story; it signals to me the writer’s intended tone, rhythm, and so on, which helps me know how to read the piece. That can mean lyrical prose, and it can mean pragmatic, utilitarian writing; both can be wonderful. What I want to do in this last section isn’t give specific stylistic recommendations but discuss three sentence-level decisions I see a lot of writers make that shut me out of the story, either by flattening it and making it seem less alive or simply by making it hard to follow.

Clichés

Clichés make a story feel less alive because they’re substitutes for meaning, for specificity: if a character avoids something “like the plague,” the phrase acts as a shorthand, telling me what the writer wants this sentence to mean to me without their having to write a sentence that would actually mean it. It also makes the piece feel generic since it calls to mind all the other thousands of times I’ve heard that phrase. The fix here is simple: go through your piece and look for phrases that feel familiar to you, like you’ve heard them before; consult a list if it’s helpful. Consider ways to say the same thing in different language, but also consider that sometimes an idea presents itself in cliché language because it’s a cliché idea. If the most natural way to phrase what you’re trying to say is a cliché, it might mean you need to do more to make your characters, plot, or setting feel specific. (Clichés in dialogue can sometimes work because some people do talk that way, but they will usually make the character who says them seem boring or unimaginative, so only use them if that’s your intention.)

Too Many Close-Ups

I’m borrowing a film term to describe a particular kind of writing I see in a lot of submissions:

“Speakers throb. Feet tap to the beat. Ice melts in drinks as they’re lifted to parched lips.”

These kinds of details can be very effective when they’re paired with more clarifying scene-setting language. If the next sentence of that example is

“Every inch of the Electric Lounge is packed with dancing people, sweating through their clothes in the cramped, neon-lit space.”

then the introductory details work fine, settling easily into the broader picture. But often I see pieces that stack close-up onto close-up without ever establishing their setting or even characters. The effect is that the piece seems to take place nowhere, and I can never see the characters or the action clearly.

Having done this myself, what I found to be the cause was that I could picture the Electric Lounge very easily, so it didn’t occur to me that the reader could only picture the things I showed them. This isn’t a hard fix. Try to forget what you know about your setting and go through your story, picturing each image in turn and then as a combined sequence. If it’s hard to picture the entire space your scene is in, add a sentence or two describing it in broader terms – an establishing shot, you could say. This is also a situation where it’s very helpful to just show your work to someone else and see if they find it confusing.

Disembodied Action

“Five nights a week, Trevor would go to the lot out back of the baseball fields, where stories of batting prowess would mix with laughter and expressions of admiration.”

In the previous section, I described a common tendency in writing that makes settings hard to picture; this is similar but applies instead to characters, especially minor characters. In this sentence, who is telling the story of batting prowess? Who’s laughing, who’s expressing admiration? These things appear to be being done by no one. I’m not having difficulty picturing the place, but rather the people: the sentence is clearly meant to establish the world of this story and the things that happen in it, but the world seems depopulated, Trevor showing up to an empty parking lot.

You’re probably familiar with the advice that writers should be careful with the passive voice, but there’s no passive voice in the example above; this can happen in other ways. Be on the lookout for descriptions of action that don’t have a person attached to them. It can be helpful, if you’re writing a scene that depicts a large number of minor characters, to ask yourself: exactly how many people am I putting in that parking lot? Where are they positioned relative to each other? Are they sitting or standing? What are they wearing? Even if you don’t plan on naming all the characters, being specific with yourself about their number and position in the scene will help you make sure to give each action a body to go with it.

by Dawn Tasaka Steffler | Oct 21, 2024 | flash fiction

But I didn’t ask for a dog. I asked for Grand Theft Auto. Mom says, “There are things in that game that are not age-appropriate,” and I say, “Like killing hookers after you pay them so you can get your money back?” She crosses her arms and looks at me, her forehead wrinkling, but I shrug and say, “That stuff’s all on YouTube.”

Whistle is a lab/pit mix. I named him that because his nose whistles when he sleeps. The whistling used to keep me up, but I’m used to it now. Just like I’m used to sleeping all scrunched up because he takes up the whole bottom half of my bed. Also, he smells sour, like mustard. Mom says he smells like that because he needs a bath, and it’s my job to bathe him because he’s my dog. Also: feeding him, picking up his poop in the yard, and walking him when I get home from school. I remind her I didn’t ask for a dog; I don’t even like dogs. And she says, “You’ll be sorry when he’s gone.” And I say, “I know, I know, you say the exact same thing about yourself.”

For my tenth birthday, Dad gives me GTA when Mom isn’t looking. I know what he’s doing. It doesn’t make up for everything, but it helps. I can only play when Mom’s at work. So, every day when I get home from school, I put Whistle in the backyard and say, “I’m gonna play for one hour tops, then we’ll go for a walk, ok?” But every day, I lose track of time.

Mom’s driving like a lunatic. She says we’re gonna drop Whistle off on some country road so he can be Nice. And. Free. Because this morning, she discovered Whistle dug up all her plants and chewed holes in her hose. Then she found my GTA in my underwear drawer. And now she’s saying this is all Dad’s fault. I hate it when she gets like this, itching to teach someone a lesson. So, who’s the lesson for today? Herself? For promising the shelter people that Whistle would be our forever dog? I pretend to fall asleep so she can’t talk to me, but I actually fall asleep. And I wake up when the back door slams. Then the driver’s door slams, and she’s next to me, both hands on the wheel. I don’t look at her, but I do look at Whistle in the side mirror, sitting attentively, head cocked to the side, like a dummy. And she says, “Hopefully, some nice person who loves dogs finds him.” Then she starts the engine. The tires crackle as we go from the dirt shoulder to the road, and honestly, I’m a little shocked. I watch Whistle go from a sit to a stand, and my insides fizz like a dropped Coke. Then she says, “Hopefully, he doesn’t starve in the woods or get hit by a car.” I know what she’s doing. But I don’t say anything, and she keeps driving, and Whistle gets smaller and smaller in the mirror until I can’t see him anymore. I imagine the upside for him: no more tiny backyard, he has space now, and he can chase all the squirrels he wants. And I imagine the upside for me: no more dumping a pooper scooper full of dog shit into the super stinky poop trashcan, no more waking up with a stiff neck because I slept all crooked, no more closing the kitchen door on his big brown eyes, no more listening to his high-pitched whine while I play GTA. But the longer she drives, the more I panic that when we turn around and go back to that spot — because it’s inconceivable not turning around — that Whistle won’t be there. Maybe some stranger drives by and lures him into their car, or he sees a squirrel and runs into the woods, or he wanders onto the road even though I’ve taught him to stay on the sidewalk. But there are no sidewalks here. I’m feeling car sick. And I no longer care if Mom thinks she’s teaching me a lesson, I want Whistle safe in our back seat again. I say, “Mom, turn around.” Of course, she pretends not to hear. So, I say it again, louder this time, “Turn around, please.” It takes a second, but I can feel her foot come off the gas pedal.

Recent Comments