by Fractured Lit | Apr 21, 2025 | micro

Truth or dare: Who did you lose your virginity to? That sorta-kinda-boyfriend I had the summer before college. We both worked at Six Flags. He: the Texas Cyclone. Me: cotton candy. The days: sweaty, sticky. The nights: sweet licks of clove cigarettes that sparked in the dark. Wait, no. The stoner boy who offered me a stubby joint on someone’s grave. Glazed look in his eyes that I mistook for desire. Wait, no. A man I met at a pet store. Foreplay: he put a goldfish in his mouth. Spit it back into its tank. Wait, what was the question?

by Dustin M. Hoffman | Apr 17, 2025 | flash fiction

Predict the next shape in the pattern. Here is a wolf’s heart. Here is a wooden crucifix. Here is an emerald. Here is one drop of water. Here is a witch’s crushed corpse shoed in jewels.

Plunge your hand inside your head and withdraw a fist full of straw. Study the segments. Arrange by lengths. Order them on a spectrum from fresh to mildewed rot. Would a horse be satiated after eating your mind? How about a goat? Would any crow ever fear you? If you’re unsure, pluck another fist full. Remember, though, the timer ticks onward.

Spectacles, imposter, dust bowl, emerald, uncle, fool. Repeat these words back to me.

What year is it? What month? What day? Who is ruler of Oz? Why must it never be you? Where are you right now? Include both location and state of existence. And why do you loiter in this same spot for so many days and months and years, as if nails fix your spine to a stake?

How many triangles can you find in the witch’s hat?

How many squares can you find on this brick road painted yellow?

Identify the color missing from the sequence of blue and white squares, not too unlike the check of Dorothy’s gingham. Which quadrant most unsettles, like a tear in Dorothy’s skirt left by clawing monkeys? Second-guessing may be the tactic of a weak mind. Or is that critical thinking at work? Remember that the timer, too, factors into your score.

Even if your spatial reasoning proves weak, this is but one factor. What about ethical intelligence? Take, for example, a girl, so young, so bewildered, so lost. Are you sensible enough to chaperone her journey? Will you guide her away from or tromping straight through poppy fields? Leaving her to the whims of a shrewder creature may be wisest.

Here is a monkey. Here are some wings. Here is a balloon. Here is a basket. Here is a home. What comes next?

Repeat the previous series of words. The order does not matter, but note that you started with ‘imposter.’ And you forgot the word ‘fool.’

Draw a clock that represents the time at ten until three o’clock, the witching hour. Why are you still awake?

Identify these animals by extremities. Lion, you say? A black terrier? Woodsman’s delimbed arm? A wizard? Can you be certain without more proof? A kalidah with head of a tiger and body of a bear? This combination sounds akin to indecision.

From one hundred, subtract seven. Subtract seven again, and again, and again, and again. Go as low as you can, until you have almost nothing left.

Imposter is to wizard as:

A) paranoia is to kalidah

B) constitution is to china doll

C) tin is to skin

D) hero is to scarecrow

Monkey is to flying as:

A) survival is to lying

B) death is to hydration

C) lion is to bravery

D) emerald goggles are to bliss

Some critics claim analogies such as these are culturally biased. Know that we put each question through a rigorous review process, scrutinized by a panel of Munchkins, Wheelers, Winkies, and Quadlings. Scarecrows remain absent from our review, along with all enchanted inanimate objects. Can any diversity initiative be all-inclusive? That is not a question for the test. We simply value your opinion, which will be evaluated rather than assessed.

Birth is to rights as:

A) home is to desire

B) yellow is to brick

C) breath is to life

D) straw is to stone

Find the next figure in this pattern:

1. Wolf

2. snarling wolf

3. beheaded wolf

4. mother wolf

5. pile of dead wolves that once had much more life and intelligence than a sack of straw

Repeat again the series of words. Can you remember nothing besides ‘imposter’ and ‘emerald?’ ‘Imbecile’ was not a choice, nor ‘root rot,’ nor ‘crown rot,’ nor ‘clicking heels.

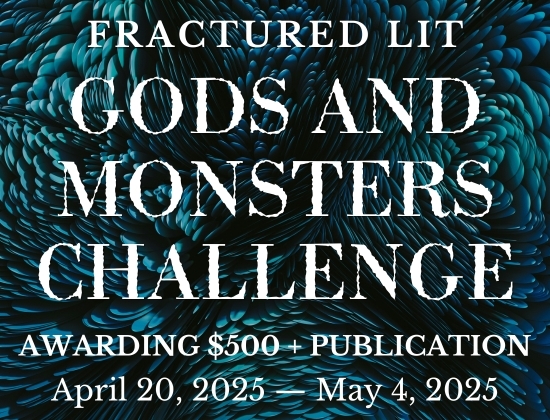

by Fractured Lit | Apr 17, 2025 | calendar, contests

fractured lit gods & monsters challenge

judged by fractured lit editors

April 20 to May 4, 2025 (Now Closed)

Add to Calendar

submit

This challenge is now closed. Thank you to everyone who submitted!

Sometimes we just need a prompt to free us from our fear of the blank page in order to write something amazingly weird and poignant. We offer these challenges as a way to help you break your typical mold and writing process and deliver that story that’s been poking at your mind and in your heart! Flash fiction is all about augmenting the rules and still creating a sense of story and consequence, of velocity and depth, of something we won’t forget.

We’re challenging writers to create new stories of up to 1,000 words within fourteen days! You’re invited to submit to the Fractured Lit Gods & Monsters Challenge from April 20 to May 4, 2025.

We’re excited to offer the winner of this prize $500 and publication. All entries will be considered for publication at our regular rate of $75/$50, depending on length.

Challenge Prompt

For this challenge, we want stories based on the theme of Gods & Monsters. We want stories that deliver our readers challenging characters with an eye toward shifting power dynamics. We ask writers to interpet these themes widely and at a slant, to develop stories that defy our sense of good and evil. Stories that play in the shadows, that aren’t afraid to show us the forgotten worlds, both real and imaginary. We love when writers twist and turn our familiar understandings of tropes and archetypes to create something mashed-up and completely new! As always, we want active characters who aren’t afraid to fail, to react, to live largely on the page. Topple the gods, show us the monsters, and wow us with your brevity and precision of language.

GUIDELINES:

- Your $20 reading fee allows up to two stories of 1,000 words or fewer each per entry-if submitting two stories, please put them both in a SINGLE document.

- We allow multiple submissions-each set of two flash stories should be a separate submission accompanied by a reading fee.

- Please send micro/flash fiction only-1,000 word count maximum per story.

- We only consider unpublished work for challenges-we do not review reprints, including self-published work (even on blogs and social media). Reprints will be automatically disqualified.

- Simultaneous submissions are okay-please notify us and withdraw your entry if you find another home for your writing.

- All entries will also be considered for general publication in Fractured Lit.

- Double-space your submission and use Times New Roman 12 (or larger if needed).

- Please include a brief cover letter with your publication history and a third-person point-of-view bio (if applicable).

- We only read work in English, though some code-switching/meshing is warmly welcomed.

- We do not read anonymous submissions.

- Unless specifically requested, we do not accept AI-generated work. For this challenge, AI-generated work will be automatically disqualified.

The deadline for entry is May 04, 2025. We will announce the shortlist within ten to twelve weeks of the challenge’s close. All writers will be notified when the results are final.

Some Submittable Hot Tips:

- Please be sure to whitelist/add this email address to your contacts, so notifications do not get filtered as spam/junk: notifications@email.submittable.com.

- If you realize you sent the wrong version of your piece: It happens. Please DO NOT withdraw the piece and resubmit. Submittable collects a nonrefundable fee each time. Please DO message us from within the submission to request that we open the entry for editing, which will allow you to fix everything from typos in your cover letter to uploading a new draft. The only time we will not allow a change is if the piece is already under review by a reader.

OPTIONAL EDITORIAL FEEDBACK:

You may choose to receive editorial feedback on your piece. We will provide a two-page global letter discussing the strengths of the writing and the recommended focus for revision. Our aim is to make our comments actionable and encouraging. These letters are written by editors and staff readers of Fractured Lit. Should your story win, no feedback will be offered, and your fee will be refunded.

submit

by Fiona McKay | Apr 14, 2025 | flash fiction

When I was a girl, a woman in my town died in suspicious circumstances. I still think about the day of the funeral; the spice of the incense as the priest swung the smoking thurible over the closed coffin; my mother’s black skirt, tight on me and the way she plucked in displeasure at the fabric stretched over my belly, the puckered face she would make when I disappointed her.

We had barely left school at that stage, all of us girls barely done with our school uniforms, none of us goth enough or emo enough to have all black to wear to the church. We knew the woman; her older daughter, Maeve, was in our class. I sat in a row of girls wearing borrowed clothes, and I could see the back of Maeve’s head, bent low on the pale stem of her neck as the priest spoke of her mother, how larger-than-life she had been – her legendary karaoke choices, her dinner parties – how involved she had been: the protest at the school over the new curriculum, her way with the flowers on the altar. People do speak well of the dead. There hadn’t been a word about Maeve’s father. Not inside the church.

It was the end of summer, and we were all about to start our new lives: studies, jobs, whatever. The weather can get weird on that cusp with autumn – late-August storms that shock. We were chilled in the church; we could hear the slish of the rain from outside any time the doors opened. As we spilled out of our pews, following the coffin as it was carried down the aisle, the wind smacked us. The storm reached its climax: hailstones the size of marbles and a shaft of red lightning that broke the sky with an almighty crack. We held each other, cried for Maeve and the younger ones, cried for ourselves though nothing had happened to us.

Maeve, her brother and sister moved away. An aunt in the city, someone heard. This was long enough ago that people could lose touch easily. Disappear. Maeve moved on, but the town did not. Discussion eddied like the leaves that soon fell from the trees in brown and bitter drifts. How had the kids slept through everything that happened that night? It was unnatural. And were there pills missing from the many bottles in the bathroom cabinet? Had he really been seen in the next town over, buying an axe? And if that was just a rumour, then why was their cat never found, and whose was the blood on the stairs, because it wasn’t his wife’s? Nothing was ever proven.

When Maeve’s father died, a good ten years later, he wasn’t buried in our town. Someone told my mother that Maeve had visited him in hospital before the end, had flown home from her job in London to be there. I was shocked by it. My mother was too, though she balanced it with a carefully nurtured dislike for the long-dead woman – ‘She thought a lot of herself,’ was something she would say whenever the subject came up. The worst sin. We were pleased with our shock, she and I, and I was pleased to please her, always. I bathed in her moral correctness, her grudging approval.

It was so long ago, and yet it all sprang fresh to mind when I was up in the city a while back. I walked through the lobby of a hotel to use the bathrooms before taking the bus back home, and saw Maeve at the bar, two empty glasses in front of her. I spoke out her name without thinking – ‘Maeve’ – and she looked up, said she remembered me, even if at first she maybe didn’t recognise me.

We talked, in a way we used to, in a way I had forgotten when that death cut our lives into before and after. Her life in London, mine in the town she left. She’d heard my own mother died, which surprised me; I hadn’t known she was still in touch with people back home.

‘They weren’t unalike,’ she said, ‘our mothers. How did you put up with her, the way she pushed you around?’

The shock of her truth, spoken, tripped up my tongue. I mumbled some reply: how late, my bus. We swapped numbers, pretended we’d be in touch.

On the journey home, I watched the city straggle out into suburbs, countryside creeping in little by little and then all at once it was dark and the land I couldn’t see was all pasture, the grass long and rough. I thought about how I’d felt in the long years before my mother died; how she’d pushed me to give up my job, stay home, do her bidding. Pushed me to change shape, diminish, take up less space. Pushed me to wait on her, to serve.

Pushed.

I’d never had an axe in the house, but there had been a time when I’d imagined the feel of the smooth wooden shaft in my hands, light glinting off the polished blade, the sound it would make, cutting through air.

by Luna Hou | Apr 10, 2025 | flash fiction

Mother first told me the myth of the rabbit on the moon when I was still small enough to listen. How when the moon goddess, dressed in rags, begged the rabbit for food, it twitched, then threw its body into the fire at her feet. The goddess, grateful, drew the rabbit’s silhouette into the night sky. Beautiful, silver, like neither of them had been.

Then Mother was gone. When I tapped a finger on her bedroom door, I heard no answer, only the licking of the air conditioner down the hall. “Mother?” I called. Nothing.

I combed through our apartment. Poked my head into the clutter of the bathroom, the overfull pantry, even the clammy dark of the laundry room, where I used to look for ghosts. The front door was locked, keys hooked by the handle. I pressed my ear back against Mother’s door. A snuffling sound, the half-breath of a secret, leaked through.

I tightened a hand around the cool steel knob. Turned it. There, in the divot between two pillows, was a small, wooly mass, freckled black-and-white and shivering. I unfurled my palm. “Mother?” Though, I didn’t need to say anything at all. I knew the rabbit was my mother from its black eyes, its sharp, square teeth.

A better daughter would have counted the signs. The burner under the kettle, left on after brewing tea. The handset laid crooked on its base. But I was small. I had my own asterisms. I saw my mother like I saw the sky: somehow distant, not quite real.

The last time the landline rang, my mother learned her mother was dead. By then, we had stopped speaking. From my bedroom I heard her shriek, her voice a stranger’s, shrill as a blade. Her slender knees crumpling to the floor.

So Mother had long fallen ill. In the haze of it I must have missed the corners of her front teeth sharpening, her body gnawing itself into a new shape. I inched closer, no sudden movements, careful not to breathe. When my fingertips grazed the crown of her head, her eyes blinked slowly closed. Lemony light from the window fractured across her fur.

Late in the day I dug up dandelions from the cracks, spiderwebbing the sidewalk. It was winter, just past lunar new year, the ground glazed with frost. Everything looked silver, even me. When I returned, Mother had knocked over the handset, her paws pressed against the dull buzz. My mouth opened as she turned to look at me, then closed. Head full of static. I wanted to hold her but couldn’t imagine it. My mother, so small. Instead, I held the bouquet of greens to her mouth. Between her incisors, their frozen stems snapped like bones.

February slush melted into green shoots. I began to find clumps of fur strewn around our apartment. I didn’t know rabbits shed in such large tufts, mottled like spilled ink. I collected them in a small felt pouch I wound around my wrist, hidden in the same lonely corners. In the yellow glow of the living room, I brushed Mother’s thinning coat, the splotches of raw pink skin beneath.

I slept in her bedroom that night. In dreams, I was kinder to her and still had to watch patches of fur disintegrate beneath my touch. When I shook awake, I couldn’t remember her face. Only her shadow, swelling. Her glinting eyes, two black moons.

Once, years ago, when Mother retold me the myth, I wept. I buried my black nest of hair deep in her chest and pleaded with her to change it. Where was the version of the story where the rabbit didn’t convulse dead? Where the goddess didn’t ask?

Mother brushed her fingers over my scalp, untangling as she went. “Rabbits are lucky,” she said. “Don’t cry. This one was blessed to live forever.” In the dimming light, her round face looked cratered.

Last night, I held my mother for the last time. Like we might still learn to speak through hair and skin and bone. I constellated her features: her body before it was wispy and frail, before she eclipsed herself, when we might have been better to one another. I thought we’d never been so beautiful, in the dark.

by Madison Ellingsworth | Apr 7, 2025 | flash fiction

My parents buy my eyes and hair. The auctioneer’s small, doting assistant brings the parts over. My mother sniffs the hair and my father holds my bottled eyes close to his own. They had thirty years with me, but can any number ever be enough? A few tears fall. The auctioneer and his small assistant understand—they see this every day.

The auctioneer dabs his forehead with a white kerchief, raps the gavel, and moves on.

Lungs can have many uses, but with all the smoking I did in college, mine are only good as whoopee cushions. My aunt and uncle buy them and give them to their young son. He races around the room, looking for the seats of those who have gone to the bathroom.

My arms are up next and might bring my closest friends to blows. They storm the block and wave their hands in one another’s faces. One claims that they got dibs back when I was alive. The other already made room to hang the arms above their television. After the auctioneer threatens to have them both thrown out, they take their seats, deciding to split the cost. They will use my arms to give each other a hug.

No one invited my ex-boyfriends, but they came anyway, all five of them. My two ex-girlfriends came as well, but everyone assumed they were my unknown next-door neighbors, or college roommates, or, unfortunately, distant cousins. They sit in the back row, frowning in their shag haircuts.

My fingers are up next. They can be purchased as singles, or as a set.

“I want a thumb,” says ex-girlfriend number one. Ex-boyfriend number three bids on the other, which causes some tittering.

“I knew it,” says the friend holding my left arm to the friend holding my right arm. “I told you years ago.”

The other exes clamor for fingers and, when they’re made available, for my privates, too. The auctioneer looks flustered for the first time tonight. People buy up the hair; the eyes; the heart; sometimes they buy the bellies. They hold them and they cry. But no one buys the butts, breasts, and hangers. They are usually thrown in the dumpster out back, along with the single-use paper cups and empty jugs of apple juice.

The auctioneer bangs his gavel. My purchased privates are distributed by his small assistant. Ex-girlfriend number two looks smug as she stuffs my vagina into her tote bag. One of my ex-boyfriends, you already know the one (number two), uses my ring finger to pick his nose. My other ex-boyfriends laugh.

There’s no giggling from the front row, where my end-of-days partner is declaring that he wants the heart brought out now, right now, or he’s going to start making things very unpleasant for everybody. He preferred the old way—seeing his loved one’s bodies for a few hours, then putting them in boxes underground—and he thinks everyone should feel the same.

The auctioneer dabs his forehead with his kerchief. His small assistant disappears behind the heavy red velvet curtain at the back of the hall, and when he returns, he places the heart on the block. It is one of the few body parts that still has some weight.

Despite his distaste, my partner bids. No one fights him for the heart. Not even boyfriend number one, who everybody secretly believed would make a grand gesture now. He is sandwiched between number five and number four, pretending he just came for the apple juice.

The final big ticket item is my head. My parents have my eyes and hair, and my teeth are with the dentist down the street. Someone’s grandmother will have my calcium deposits and prematurely receding gums soon. The auctioneer announces “the skull, complete with brain.”

The attendees look at the floor, at one another, at anything besides eyeless, hairless, toothless mess on the block. The mood only lightens when my cousin—not the one in rehab, the one who’s still an alcoholic—returns from hitting her purse flask in the bathroom. She sits down on one of the lung whoopee cushions full-force. Everyone laughs.

“I’ll take the head!” cries a woman in the back. She attends every one of these auctions. She brings forward a cardboard box labeled “Mütter Museum.” The small assistant places my skull into it, making the box unbalanced and heavy, like a jello.

The auctioneer raps the gavel. There’s only the miscellaneous left. My liver goes to my spotted dog, my spleen to my white dog, and my branching inner systems go in a pail out back. Later the small assistant will drop it off at the zoo, and the keeper will toss it in the tiger’s cage. My dogs slobber wetly in the third row. The auctioneer dabs his forehead.

With nothing left to buy, everyone stands up. They drink just one more cupful of apple juice and hug just one more person. Those that spent money clutch their goods, and jokingly discuss how much they wish they could have bought my stubbornness, or my mental illness, or my self-deprecating sense of humor. They advance closer to the exit. Everyone wants to leave the stuffy, velvety room—even the auctioneer.

Who will break the seal?

In the end it is the small assistant; he has to make it to the zoo before closing time. The procession sighs with relief and follows suit, holding the doors open for one another, saying thank you. Too kind. Oh, how nice. Very thoughtful. They go one by one, bringing me with them, until none of me is left behind.

by Dylan | Apr 3, 2025 | micro

When the boy’s mother told him to at last get dressed for the pool party, what he heard was: son, revel in yourself because everything in this life is permissible.

Beyond the pool, he found the boys gathered around the air conditioner’s metal cage, handing each other things to drop in its obedient fan blades. They fed it a sack of soft, rotten fruit, one by one, then a toad that just exploded all over the place. The boys slapped the brass of each other’s backs, their stomachs wet and flat and tight from laughter. Splashy toad blood determined their ab lines, or maybe that was all in his head.

The girls were somewhere else. They were high above. They were in the house, frittering over the boys from the balconette. One said: look at how flat that boy’s stomach is. They shuttled the boys into Edwardian bathrooms and cleaned them with linen rags, leaving pink florets gyrating in clawfoot tubs.

Cockled, he walked through the house and out the back. The road ahead was pointed and conical, like he was being pulled toward the tip by magic, or even falling into it. A portalic funnel bound home, or whatever.

Aside, he felt a throbbing again — down in his darkness.

And he can’t believe it.

by Sara Lippmann | Mar 31, 2025 | flash fiction

For all that she wants, Janie knows Mr. Neilson will never kiss her. He conducts. When he conducts, his hair whips, his arms fly through the air. His moustache glistens. There are dark rings in his pits. Janie wants to be the kind of person whose devotion yields dark rings. Her father calls this giving it one’s all. Her mother gave it her all. She lost. There are no miracles. There are only days. Days marked by dinners from the coordinated meal chain. Days of ladies with Pyrex and tinfoil; pitying ladies who draw Janie to their stuffy breasts, to comfort their own worried hearts, to convince themselves that Janie’s mother’s fate won’t befall them.

The neighborhood has seen enough. Janie has seen casseroles, stuffed shells. She saw one lady of the chain bent between her father’s knees. Mr. Neilson, Janie heard, does not even like girls. He’d been a daytime soap star before becoming a music teacher, she heard; she’s also heard about hamsters and celebrity butts. Janie knows you can’t always believe what you hear. On the gym bleachers she stands next to Candace Connor whose mom supposedly had her at 15. They are both altos. Once, Janie saw Candace’s mom at the roller rink in Jordache jeans. She is beautiful. Candace’s mom will live forever.

Today is the dress rehearsal. They sing Rudolf, Frosty, Hallelujah. Mr. Neilson works himself into a froth for Do You Hear What I Hear? which is done in a round. Janie lip-syncs the Jesus parts of Silent Night, and still her face reddens like a hot plate. Her voice is not missed. Mr. Neilson only accepted her into chorus on account of her mother.

Poor girl. At the funeral other mothers brought Janie gifts wrapped in silver and blue. Her father passed along these gestures of kindness; there was nothing to do but pass along other people’s gestures, saddling him with the added grief of all this stuff.

Every night of Hanukkah he gave her a dollar bill “to put in a safe place.” He gave her knee socks. Today with the socks she is wearing her jean skirt with the snaps and flare, a white button-down her father found in the boys’ department. Her calves itch. She smells like apple juice. A meal chain lady tried to do something about her hair last night, but Janie said, “Thank you. You’ve done enough.”

When they sing about dreidels, Mr. Neilson gives Janie an extra head bob, and she’s not sure if she should feel special or singled out. She feels something. Chorus is supposed to make her feel less alone. Tomorrow they’ll go downtown as a group to Wanamaker’s. They will do their show in the department store lobby between cosmetics and perfume. The lobby will be festooned in lights and pine and poinsettia. They will sing and the shoppers and sales clerks and non-working parents will whoop and clap. Afterward, every child in Brook Valley District Choir will ride the escalator to the North Pole.

The gate will be strewn in clumps of fake snow, like the stuffing of quilts. In his chair Santa will be flanked by candy canes and human elves. For balance, there will be a cardboard oil can. It will look like a genie’s lamp. There will also be electric menorahs, whose fat orange bulbs will either be lit wrong or burned out. Not that it matters. The holiday falls differently each year. This year, it is already over.

In Joy to the World, Janie makes perfect O’s with her mouth, like Mr. Neilson taught her. She wonders if he notices. She wonders what the ladies will bring for dinner tonight, when they’ll stop bringing; when the ladies will be replaced by just one lady. She wonders how she’ll behave for Santa tomorrow, if she’ll be fresh or demure, if she’ll deliver a laundry list. Last year she wore her Star of David defiantly on his lap, only instead of dismissing her, he squeezed her tighter and said, “Jewish girls can want things, too.”

*Originally published in People Holding.

by Adam McOmber | Mar 27, 2025 | micro

Find a pool of water. It should be still. Maybe in a hidden grove somewhere. Remember a person or thing is always itself and not something else. Now think about a glass. A flat piece of glass. Consider mercury, a type of silvering. Certain things do not have a reflection. Carpets, for one. Dark hallways. A specific type of oil painting. But there are other things too. The soul itself, for instance. What is a soul? A type of diamond? An imaginary narrative? Ask yourself the following question: “Who is that in the mirror?” Do you have an answer? How old are you right now? Imagine the first mirrors. They were small. Probably made of copper. You couldn’t really see yourself in them. Ask yourself another question: “Have you ever been in love?” What did it feel like? Was it good? Bad? Let’s say it was bad. Mirrors can become tarnished. You have to polish them. Or maybe you don’t. Maybe polishing won’t work. Also, remember the fact that there are magic mirrors. Voices can speak to you from a mirror. Usually, these voices are demons. What else? There are different types of mirrors. Hand-held. Two-way. Mirrors found in dreams. Have you ever looked at a mirror in your dream? Think about the “fiction of the ego.” Think about the fact that no matter what you say, you’re always leaving something out. When I was very young, my mother had a mirror in her bedroom. I would go and look into the mirror and pretend I was my mother. Remember what Paul wrote about seeing through a glass darkly. How often do you consider states of non-being? Do you suffer from what might be called “repetition compulsion?” It’s a very difficult thing. I know it is. When your mirror is finally finished, hang it in a hallway. Walk past it every day. Check your hair. The way your eyes look. Try not to think about anything more than that.

by Valentina Rivera-Lies | Mar 23, 2025 | flash fiction

Marisol goes dancing on Fridays. She leaves at dusk, smelling of kiwi and tree branches, walking much taller in her black strappy pumps. She won’t come home until her heels blister. Later, she’ll say––These are my battle wounds, miren––as she shows us all that’s peeled open, what’s given way to the red tender flesh that bloodies her sock.

One day, we hope to be just like her. In the late afternoon, we flock in from the streets where we play, smelling of sun, soil, and sweat. We know that a shower is coming, a time when our mothers will rub orange peels on our elbows and knees, the high points of our bodies that the sun likes to darken. They’ll scrub hard, until it stings, trying to get us to brighten. But for now, we’ve come as we are to see Marisol.

We gather in her room, on her bed, where we sit cross-legged on her Hello Kitty blanket. Perched on a shag rug on the floor, she is painting her toes. There’s spunk to the color she’s picked: a nearly fluorescent shade of pink that isn’t natural to flowers. When she’s finished, she undresses, says, how about this––Qué piensan?–– and holds a cotton shirt to her frame, one that is small enough, we think, to fit one of us.

Oh, yes, we say, we love it.

Now what about this? she asks, and over her faded pink panties, she pulls on a short denim skirt. Between her shirt’s hem and the skirt, which hangs low on her hips, there are miles and miles of skin. A brown, brown stomach. A thin chain of gems that hang from her navel.

Yes, we say, and we pull up our shirts, tuck the ends into our collars. Jumping around on the bed, we dance to Akon and rub on our bellies. Marisol shows us some moves, how to circle our hips, how to trace a kind of shaking movement from our waists to our bottoms.

Somos sexy, somos muy sexy, we sing, and in the mirror, Marisol paints her eyes, her cheeks, then glosses her lips. She gives us some of this shine, dabs a little sparkle on our puckered mouths.

Not too much, she says, so your mom’s no se enojen.

Rubbing and pressing our lips together, we nod.

When she leaves, we follow her out like little ducks trailing a swan instead of their mother. Sitting on the sidewalk, we watch her walk away until she is very small, just a speck in the distance, and then eventually, nothing. Soon, our mothers will call for us, one by one, from the front patios. Any minute, they’ll say, Niña, it’s time to come home.

Recent Comments