by Fractured Lit | Feb 23, 2021 | contests

ghosts, fables, and fairy tales prize

judged by Rumaan Alam

CLOSES April 17, 2022

submit

We invite writers to submit to the Fractured Lit Ghost, Fable, and Fractured Fairy Tales Prize from February 25 to April 17, 2022. Guest judge Rumaan Alam will choose three prize winners from a shortlist. We’re excited to offer the winner of this prize $3000 and publication, while the 2nd and 3rd place winners will receive publication and $300 and $200, respectively. All entries will be considered for publication.

Rumaan Alam is the author of the novels Rich and Pretty, That Kind of Mother, and the instant New York Times bestseller Leave the World Behind. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, New York Magazine, The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, Bookforum, and the New Republic, where he is a contributing editor. He studied writing at Oberlin College and lives in New York with his family.

Fractured Lit is looking for stories of ghosts, fables, allegory, and fractured fairy tales in 1,000 words or less. Using these genre themes please remember that we’re searching for flash that investigates the mysteries of being human, the sorrow, and the joy of connecting to the diverse population around us. We want something new. Something that scares as much as it resonates; stories that help us discover the roots of desire and conflict, that shimmer on the page, that keep us reading, and wondering long after the last period on the page. Transport us from the here and now to a new land of discovery, a new way of being terrified, a new way of embracing all of the ways we show our humanness. Fractured Litis a flash fiction-centered place for all writers of any background and experience. Good luck and happy writing!

GUIDELINES:

- Your $20 reading fee allows up to two stories of 1,000 words or fewer each per entry-if submitting two stories, please put them both in a SINGLE document

- We allow multiple submissions-each set of two flash stories should have a separate submission accompanied by a reading fee

- Flash Fiction only-1,000 word count maximum per story

- We only consider unpublished work for contests-we do not review reprints, including self-published wor

- Simultaneous submissions are okay-please notify us and withdraw your entry if you find another home for your writing

- All entries will also be considered for publication in Fractured Lit

- Double-space your submission and use Times New Roman 12 pt font

- Please include a brief cover letter with your publication history (if applicable)

- We only read work in English

- We do not read blind. Shortlisted stories are sent anonymously to the judge.

The deadline for entry is April 17, 2022. We will announce the shortlist within 8-10 weeks of the contest’s close. All writers will be notified when results are in.

- Some Submittable hot tips: – Please be sure to whitelist/add to contacts so notifications do not get filtered as spam/junk: notifications@email.submittable.com– If you realize you sent the wrong version of your piece: it happens. Please DO NOT withdraw the piece and resubmit. Submittable collects a non-refundable fee each time. Please DO message us from within the submission to request that we open the entry for editing, which will allow you to fix everything from typos in your cover letter to uploading a new draft. The only time we will not allow a change is if the piece is already under review by a reader.

OPTIONAL EDITORIAL FEEDBACK:

You may choose to receive editorial feedback on your piece. We will provide a global letter discussing the strengths of the writing and the recommended focus for revision. Our aim is to make our comments actionable and encouraging. These letters are written by editors and staff readers of Fractured Lit. Should your story win, no feedback will be offered and your fee will be refunded.

Good luck and happy writing!

submit

2021 Winners:

1st Place: A Guide to Small Town Ghosts by Regan Puckett

2nd Place: The Changeling by Sarah Boudreau

3rd Place: A Too Small Room by Yume Kitasei

Honorable mention: The Bone Child by Meagan Johanson

Honorable mention: god at the side of the road by A Poythress

Shortlist:

A Guide to Small Town Ghosts Regan Puckett

The Better to See D.E. Hardy

This Is How You Become a Myth Ophelia Hu Kinney

El Triste Eric Scot Tryon

The Changeling Sarah Boudreau

The sixth-eldest dancing princess looks back at her legacy Madeline Anthes

The Bone Child Meagan Johanson

Recorded Live dm armstrong

Nosebleed Weather Marilyn Hope

A Too Small Room Yume Kitasei

The Sea Witch Lindsey Kirchoff

Springriven Olivia Frost

The Day The Moon Fell Iona Rule

Scratchers Corey Farrenkopf

Bitter Doll Susan Power

Bloodcoat Carolyne Topdjian

Shame Street Anne Perez

The Eaves Audrey Burges

Dialogue Between a Woman and Her Ba Faye Brinsmead

Ornithology for Girls Tara Stillions Whitehead

Women’s Work Carolyn Jack

His Mother’s Teeth KC Mead-Brewer

god at the side of the road A Poythress

by David Morgan O'Connor | Feb 22, 2021 | flash fiction, micro

Plan to Free

The dog ate the turkey. Then killed all the village swans, piled the white corpses at the front door, impossible to hide, a pyre to be paid for with exile. In the orange school bus, every morning and afternoon, no matter the snow or dust, we’d lower the windows and hang out from the waist yelling across the rutabaga fields and hail our dog chained to a tractor tire. We conspired to pedal under star-cover with chain-cutters and hairpins to pick locks and unleash dreams. We planned escape routes down beaver creeks, flow-following to great lake mouth, over the falls, to sea salt. We’d be Vikings Conquistadors Voyagers Braves; the first to find the strait. We’d live off seal pelt and whale blubber and albatross breast. We’d suck octopus tentacles to keep scurvy at bay. We’d breed a whole continent of dogs, horse islands, cat jungles, pig mountains. In winter, we’d burn the news for warmth, asking for nothing, saying nothing to adults, which we’d never become, a fate equivalent to death. Our arms would turn legs. Our snouts would grow long. Fingers to paw. Our ears would hear everything.

Abandoned Wheels

I machete the avocado. The blade divides the pit ball. Green meat spreads open. Two thighs. The average avocado tree takes fifteen years to produce fruit. The oldest, still growing wild in Mexico, is over four hundred years. With the same blade, I open a coconut’s fontanelle, miss my mouth with the milk. Peeling a mango, I decapitate a thumb, mixing blood, juice, and barefootcrushed papaya seeds, we sup till rescue, which came far too early. Brother, we grew apart.

The night heat dripped sweaty our eyes. Skin dried to salt- leather. Hide. Jerky. Actually saw sparks when we talked. In 1934, 804 men and 140 women leapt into the same volcanic atoll crater near Japan. I can’t even spell your name in the sand anymore, the last to grasp continental drift. Drift is not at fault. Whittle stick to be still, a testament, final will. As fast as a bucket dropped into a poisoned well banana plants sprout where you once stepped. Green jackfruit dangle just beyond reach. Unfinished horizon pray for us. Our Lady of Lack of Decision open the confessional, I’m ready to accept Last Rites. Please administer.

A sacrament, a decade, a loyalty card, would we return if we could? Is there anywhere around here to buy a bottle of belief? The attention we draw—Look! There’s a port. Just in time, the clouds are darkening. Is that a daylight star falling? Is the harbourmaster really twirling his mustache? Denying entry. Let’s trade him fruit for stamps. Let’s learn the native slang before the shore. Can I put my head on your shoulder? No touching. Our pit deviates toward germination. Our seeds grow wings.

Fly bitches fly. Come closer, go away, let me watch.

Puttanesca

You can’t force these things. For the first two years after my brother’s death, I could only remember the teasings, headlocks, and beatings. He was always trying to teach me to be tough. You have no respect. You have a soft head; he’d say between thumps. Now, approaching three years, I’m cooking a puttanesca, which to means to me every bitching thing left in the house into the pot: canned corn, sliced cucumber, diced onion, crushed garlic, melted cheese rinds, jarred tomatoes, salt, black pepper, cayenne, soy sauce, lemon juice, dried basil flecks, and two old yolks cracked raw.

I’m wearing a clean white wife-beater which we never wore back then. It would have been called an under-vest or something else unrelated to domestic violence. His hand-me-downs were always collared or buttoned or too big. I pour myself some port and add three fingers of tonic and sit on a stone outside the front door in the sun waiting for the gunk to congeal on the spaghetti fused linguini—mixed girth, same shape, different cooking times—who cares about time? We never cooked together, rarely ate together except when forced. When he drove, I couldn’t touch the radio or speak and suddenly unawares, I don’t know if it’s a memory or a presence or sensation, but I chuckle aloud about taking my white shirt off and eating bare-chested, so the sauce doesn’t stain.

I don’t remember if he did it or said it or we did it together or maybe a friend said or did it and we laughed or we saw it on television together we did watch loads of shows together for years. We were latch-key kids with no keys because there was no need to lock doors. He forced me to excellence at sports and to be unafraid of anything except fear itself. Taught me to fight so I never had to. Anyway, I’m tough and respectful and eating shirtless hoping to splatter blood-coloured sauce on my skin.

The Anatomy of Stalk

I’m trying not to use trauma as currency. How many duty-free purchases have proved shitty gifts? When I stood by your casket and saw the make-up, I wanted to strangle the artist. Kaufman & Sons, the undertakers who we’d known all our lives, played football with, crashed snowmobiles with, tapped maple trees for syrup with, asked what I thought. You were not your body. That body—appeared three times your age in a bad suit, cranberry-juice lipped, cheeks parchment yellow, not a sunset over the frozen lake, eyeliner from hell.

Hell, I said, good job. Thanks for the rebate on the box, too. Earthworms don’t know mahogany from oak or plywood. My face squeezed to grape, arms involuntary punched the back porch door, off-hinge swung, cigarette already lit, I said nothing to the cornfield. The gravel road responded with tires. The guests are coming to pay their respect. Fat faces and old names. Some auras unchanged, just as we left them, some unrecognisable, some some some. I stood beside my father and pretended to be strong, healthy, good. Handshakes, hugs, back pats, tears, even belly laughter.

Stormin Norman, the skinny lawless linebacker, reeking of rye and tobacco put me in a headlock, your brother, took me under his wing, got me laid once, no one liked me then, no one likes me now, except him. He changed my life and now that ain’t him. I just heard this morning, got released yesterday, drove all the way down from fucking Tobermory. Fuck me, that ain’t him, in that box, that ain’t him, that’s just a body, your brother was a god.

From the parlour window, see Norman pull donuts on Kaufman’s gravel, blasting his Camaro horn, an empty bottle out window tossed into the waving tassels, silk, ear, kernel, sheath, blade, root, tiller, seed, engine gunned over the low hill into the forever night. Another slender attachment recedes into the distance.

by Emma Stough | Feb 18, 2021 | flash fiction

From the time I learn how to bleed I keep a scab in the fleshy inner curve of my ear. Small, coarse, red-brown. I tend to it like I should tend to myself. When I am lonely, or need something to ruin, I dig a fingernail into the cartilage, tear the scab. Little blood, bearable pain. I like being in charge of how I feel. If this is being selfish then I am definitely selfish.

At my job, I pick the scab and squint at it on the tip of my thumb while selling lime green diet pills to women who can talk for hours about their skewed body image. I am required to tell you I get paid for this, I tell them. $7.50/hour. They tell me this is terrible compensation for all I put up with.

I keep the scab a secret because I once told a boyfriend and he asked to see it. When I showed him, he licked my ear, and the scab fell into his mouth, and he swallowed it whole. He blinked at me in surprise. I felt an unbearable pain.

There is no medical cure for having a body, the women who don’t need diet pills tell me. This is how I will look—and feel—for the rest of my life.

As a kid, I kept the scabs in an empty gum tin under a loose floorboard. Sang them lullabies.

One of the women buys three whole bottles of lime-green pills every month. I think she is in love with me. Tell me something you wouldn’t tell any other customer, she says. I check to see if my boss is watching. I tell her about the scab. She asks what caused the injury. I ask, What injury?

We meet for coffee in autumn, then winter, then spring. In summer, she asks me to take a trip with her. The diet pill company has gone under and my scab has doubled in size. It requires a little more force to extract; one long sting.

The flight is delayed. I check on the scab in the airport bathroom. I dig around in my ear. It’s nowhere to be found. Fingernails etched in blood. I tell the woman that I have to go home, that something terrible has happened. Take me with you, she says. Your ear is bleeding. A feeling along my legs, prickling, like I’m shaving with cold water. Good luck with your body, I say. In the cab, I make a phone call. And what’s the reason for your visit? After a moment of thought, I say: Disappearing parts.

The doctor asks me what’s wrong. His last name looks like “apricot” but is not pronounced the same. I tell him that the scab in my ear has disappeared. He says, You’ve healed? I try to explain that it’s not the healing I’m worried about; it’s the absence of pain. He shakes his head, like he’s disappointed, and scribbles a prescription out onto a pad. I take the paper and grip it hard through the hallway, through the waiting room, through the parking lot. In the car, I unfold it and find he’s written something absolutely illegible. Absolute gibberish.

Sometimes, when I try to remember what it felt like to be in charge of the removal and the regrowth, I imagine the paper said something like: It’s okay that you’ve handled things wrong. It’s okay to get worse, and worse, and worse.

by K.B. Carle | Feb 12, 2021 | news

This past weekend, I did a deep dive into flash ghost stories. I leaped into the realm of flash specters and those that haunt with an open mind, not in search of something clearly defined as I did when researching flash Fairy tales and Fables. I wanted to find stories reminiscent of Casper, the Friendly Ghost (even though I’m a fan of the conflict caused by the presence of Uncle Fester and Spooky), Ghost Busters, with a pinch of Inky, Blinky, Pinky, and Clyde (the ghosts from Pac-man for the non-nerds out there). As you polish your ghostly tales for Fractured Lit’s Ghost, Fable, and Fractured Fairy tales contest, consider telling a different kind of ghost story. I’m drawn to the stories below because each contains a different perspective regarding the haunted house, a banshee, friendly ghost, or spirit.

Mao’s flash is what I would call a deconstructed ghost story. This isn’t Scooby-Doo screaming, AH A G-G-G-GHOST! Instead, the title and the following three paragraphs depict the haunting elements within this flash, the entrance of an ex-ghost. What I love about Mao’s story is the focus on reality, the grounding elements of the two characters living and growing together. Therefore, the ex-ghost is not a soul floating in and out of the narrator’s life but rather a companion, an actual being that learns how to interact with her sister, who knows how to be alive. The will to learn compared to the intimate relationship shared between sisters left my emotions shattered in the best way at the story’s conclusion.

What happens when a ghost has unfinished business? Better yet, what happens when the living have unfinished business with the ghost that haunts their home? Edwards provides a chilling story of a narrator who is happy to see his father’s ghost again, despite his wife and child’s unenthusiastic reception of this unknown figure. Much like in Mao’s flash, the familial ties are still present within this piece, but what I love in this flash that sets it apart is the narrator’s attempts to excuse his ghost-father’s behavior. “He was always absentminded, you know.” I don’t want to spoil the ending but, as you work on your ghost stories, consider if your ghost or those who are still living are ready to say goodbye to one another and how, if one or both are not, how that impacts their interactions with one another.

If you haven’t read anything by Noa Covo, best to prepare yourself because she is taking on the flash world by storm. I am already a fan of her work and this story continues to be one of my favorites. Covo’s flash is a lesson on not only what the title states but how to make your ghost unique. There are instructions but also rules to follow, ways to appease the ghost Covo has created. Even methods on how to alter your life to make the ghost more comfortable. The grounding element, what ties the story’s “you” and the ghost together, is the music but the personality and life Covo breathes into the ghost’s character reveals more about who this spirit once was and who “you” are in this world the author has constructed.

So far, I’ve provided stories revealing the ghost as a secondary character. But, what about the ghost as the main character? There’s a careful tightrope to balance on when writing from the point of view of a ghost and Phillips flies across it with ease. We are given hints that not all is well with Mary as she plays MASH in the first sentence. Consider Phillips’ decision to subtract the term “ghost” from her story. Why? This story is about something much bigger, a life lost yes, but trapped wondering what could have been if they had lived another year, week, or day. The age of this ghost also plays a vital role in what the cost of a life lost too soon really is and heightens the sense of time standing still for a spirit who cannot remove themselves from the place they ceased to be.

My list would not be complete without a story by Cathy Ulrich, who continues to transport readers to different worlds and across universes through her multiple flash series’. For this list, I’ve chosen a flash from her Girl Detective series. We’ve discussed ghosts as secondary characters, main characters, relatives, and friends. What about the inclusion of multiple ghosts? Ghosts who haunt, who reach, who others can see? I love the girl detective’s interactions with these ghosts, but Ulrich provides another ghost within this story in the form of the absent father. The father’s removal from this flash is depicted by his empty seat at the table, through the mother’s actions, and the girl detective noticing his absence. When writing your ghost stories, consider all the forms your ghosts may take. In reading Ulrich’s story, consider which presence is more haunting. Is it really the ghosts who make themselves known, or the one whose absence is felt by all of Ulrich’s characters?

Further Reading:

- You Told Me to Write You a Way Out by Chloe N. Clark

- You Don’t Have a Place Here by Anna Vangala Jones

- The Haunting of Mile Marker 73 by Anne Gresham

- The Ghost That Haunts My House by Madeline Anthes

- Life Cycle by Joshua Jones

- Catherine Eddowes Describes Life After Death by Amy Sayre Baptista

- Soba by K.B. Carle

by Alvin Park | Feb 11, 2021 | flash fiction

I don’t know where Mom learned to drive. I don’t know where she learned to hold the wheel firm or belt my chest with her right arm whenever we stopped suddenly for the stray deer lying in the road, still half-breathing, or the broken homes that spilled their bricks onto the whitened dirt.

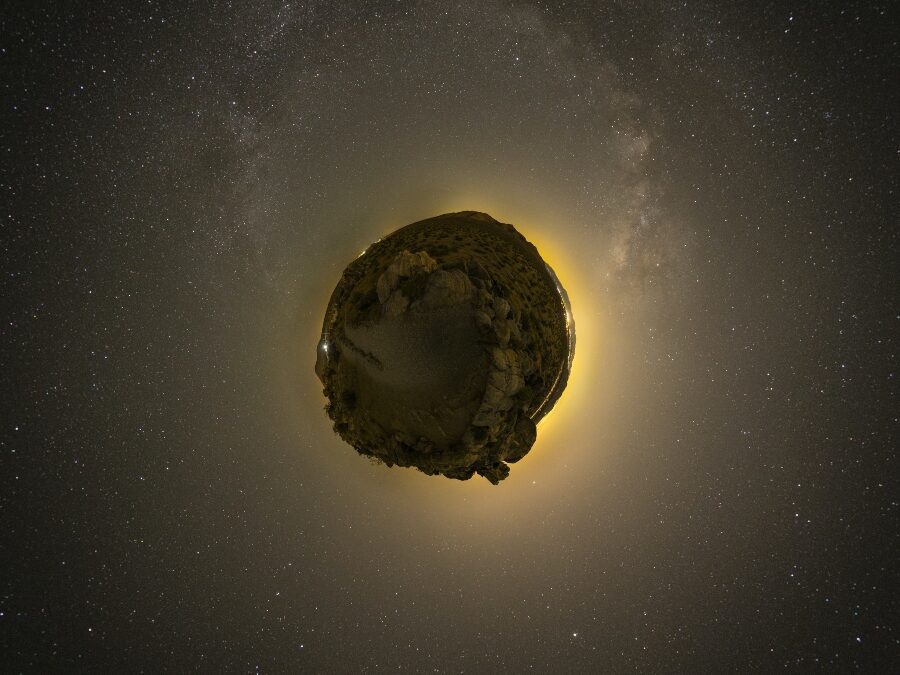

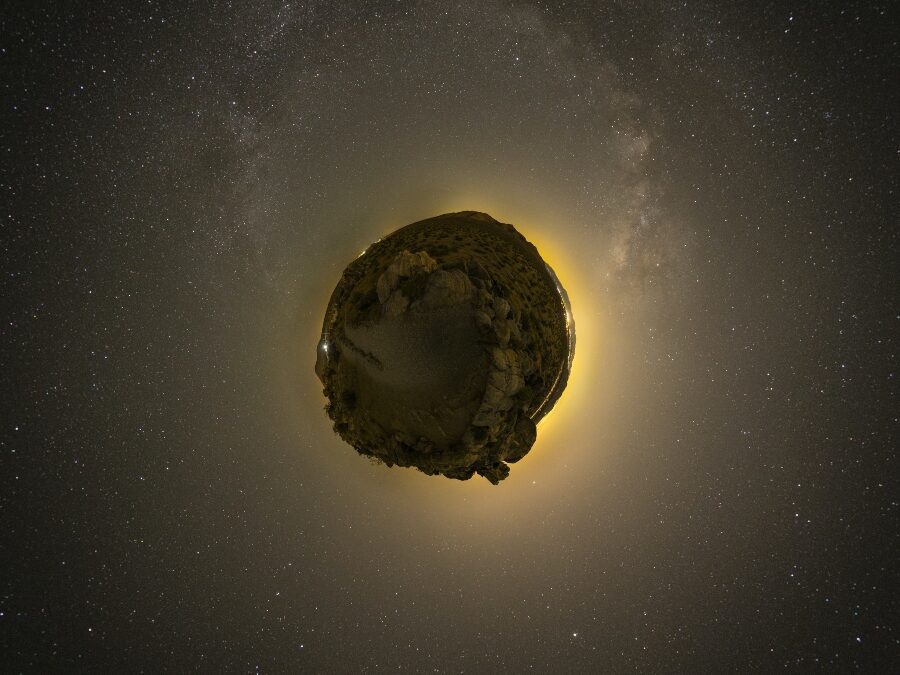

Last night, the man on the radio spoke of some rock, some piece of mountain falling from the sky. He said, Please stay clear. It will bend trees, take apart homes, melt glue and nails, turn crops to craters.

He mentioned the name of a village at the center of impact. Mom said, That village used to be home. When you were still in my belly. Do you remember?

The neighbors gave her the keys to their broken car, and she gave them the cookie tin full of coins and jewelry. They asked, Where will you go? Where will you take your little boy?

We arrived at the village, her once-home. It resembled our other village, the one we’d come from, my once-home. Houses collapsed onto their broken foundations, their walls dotted with white soot. I recognized where the gunpowder had bitten into the wood, poisoned the river with lead. I recognized where the soil had become pitted by the worms, the flies, and the boots of hungry men passing through with uniforms tied around their waists, sweat licking onto their upper lips.

With the homes vacated, the last villagers trailed down the road, shaking under the strain of books, photographs, and clay pots strapped to their shoulders. Mom watched them from the car, thought of her parents’ words from so long ago. Where will you go? Who will take you in?

She took a bag full of tools from the back of the car, held my hand as we found our way to one of the few homes with its head still lifted. I looked up at the sky thinking I’d see the shadow of that falling piece of mountain.

The door was unlocked, and the home was empty save for papers, the smell of moldy jujubes, a wooden crib tipped to its side.

She laid out the tools, and I drilled holes in the floorboards the way Mom told me: deep enough that I could feel dirt sticking to the auger, the wood coming loose like paper skin.

With the boards gone, she gave me the trowel while she held her shovel, the handle already smoothed by the months she spent clearing our fields, hoping to de-seed the fungus.

We’re digging a place of rest for that stone in the sky, she said, Dig until the ground is as tall as me and then a little more.

She raised her arm above her head, and I jumped to slap her hand. She caught me, kissed where my shoulder folded to my neck. She laughed and I laughed, and I didn’t think there could be anything brighter than the way that she smiled, held each breath between her teeth, looked at me like she knew every good thing that I could ever become.

She spoke of the stone as a seed, and I imagined grapes, plums, melons, new roots with soft voices full of juice and pulp.

Hours passed, and we stood in a waist-deep hole. The man on the radio said, You can see it now in the sky, between the stars. Impact in eight hours.

But out our window: clouds, a diffused light, a faint moon cupping the sound of cicadas.

This will have to do, Mom said, and we lay in the dirt. She held me close, the smell of lemon and perilla in her sweat. She whispered the bedtime story about the man with our surname.

They called him a war hero, she said, He sank with the ship, guided people to rafts even as he swallowed saltwater.

But he made a promise, she said.

But there is only so much to take, she said.

I fell into a dream where I heard her say, I’m sorry, maybe it’s not too late.

Morning: Mom sat in the doorway. The men on the radio spoke over themselves about trajectories. They explained that even math could fail to predict the turning winds, the way that air can prevail.

The stone skipped into the ocean, they said, No casualties.

I wiped the strange tears at her cheeks, careful not to get dirt in her eyes. She pulled me into her lap, and I asked her about the seed, the stone, the mountain. She wiped the hair out of my face and pressed her lips into my face over and over until I could taste salt through my laughs. She smiled, like a dimming sun.

I wanted to ask her why she was crying. I wanted to ask her what she wasn’t saying to me, but she turned my head and pointed over the hills standing guard outside the village.

I could have sworn, she said, I could have sworn I saw the sea there.

by Michelle Ross | Feb 8, 2021 | flash fiction

A seed is an escape pod. A plant egg detaches from its mother from the start, Jody says as she presses two speckled brown beans into each of our palms.

Jody used to just be our babysitter, but now she’s Dad’s girlfriend. “But don’t go asking your dad about it yet,” she says. “You know how he is.” She makes her voice low and stiff. Says, “Eat every pea on your plate, Laney. I’m serious. Eat those peas!”

How this came to be and what that makes Jody to us is confusing, but we like Jody. The lobes of her ears are decorated with rainbows and stars. She lets my little brother, Sam, and I style her hair and paint her eyelids with one of the eyeshadows Mom left behind. We brush the pink powder across her lids over and over so we can watch those spidery hairs flutter.

Also, she answers our questions. When we asked Dad why Mom left, he said, “Heck if I can explain that woman.” When we ask Jody, she says, “Because she’s got a disease. It’s called selfishness.” She says her own mother was the same way. Then she puts her finger to her lips and says we shouldn’t talk about this around Dad, either.

*

The lucky seeds drift away with the wind, Jody says, as we bury the beans in tiny pots filled with dirt. Or they sail streams or rivers or oceans before putting down roots. Or they hitch rides on cats’ backs, bears’ paws, or birds’ beaks. Or they get swallowed. They travel through the foul, bacteria-ridden bodies of animals.

“But fuck if they care,” Jody says.

My brother’s eyes sparkle. Cuss words spoken without hesitation or shame is another reason we like Jody.

Jody says the seeds that escape don’t mind traveling through the godawful intestines of animals because, at the journey’s end, they’re released far, far away from their mothers.

“What about the unlucky seeds?” Sam asks.

“What do you think?” she says.

“They fall down?” he says.

“That’s my boy,” Jody says.

Sam smiles, but those words, “my boy,” stick messily in my head, like the globs of glue, grayed from the grime of the day, that I’m still prying from my fingers hours after we made macaroni sculptures. We used the fancy red and green pasta Mom bought from a farmer’s market then never cooked.

“The unlucky seeds’ escape pods don’t work. They’re born in their mothers’ shadows,” Jody says.

We stare at the dirt, wondering if anything is happening yet.

*

When our bean seeds push up through the soil and split their shells in two to wear them as capes, Jody says they look poised to rocket into the air like Superman.

Sam grins, lifts his pot, and pilots it around the kitchen.

“But flight will not come,” Jody says. She looks wistfully out the window.

I look, too. What I see are the hard, green balls dotting the limbs of our orange tree. When Mom left in March, there wasn’t any fruit yet, only white blooms that she clipped and arranged in a juice glass.

When Dad calls, Jody takes the phone into our parents’ bedroom. She whispers to us, “Girlfriend/boyfriend time.”

We listen at the door, ears pressed against the cool wood. We hear Jody say, “Sure thing, Mr. Hayes. They’re in good hands.”

When she opens the door, she’s got a shimmery green neck scarf Mom left behind tied around her neck like a bow. She says, “Your dad’s going to be away an extra day. Important business stuff.”

Jody scoops us into her arms. “That’s OK, though, right? We’ll survive without him, won’t we?”

We spend the afternoon in bed with a pile of books. We admire how Jody contorts her voice in so many different directions.

*

So much can go wrong for any seedling in these early days, Jody tells us, as we water our little bean plants. When a seedling is small and weak, one injury to its flesh can ends its life. One day without water, and the seedling may crumble. Not enough sunlight, and the seedling may yellow and limp.

But for those born in their mothers’ shadows, Jody says, the biggest threat is Mother herself. If resources are scarce, she will not ration. She will not sacrifice for her offspring.

Jody removes a pan of cupcakes from the oven. Vanilla cake with chocolate frosting, both made from scratch. “The right way,” Jody said, after I pointed out that we had boxed cake mix and a tub of frosting in the pantry.

She tells us she taught herself how to bake, just like she taught herself everything else she knows. “It’s hard having no one to help you and teach you,” she says. “It’s so fucking hard.”

Jody takes off the red oven mitts, stacks them on the counter smudged with frosting. The mitts were my present to Mom last Christmas. Mom said they were too beautiful to risk dirtying. She hung them on a hook on the wall.

“But better to struggle alone than the alternative,” Jody says.

She explains that if little seedlings growing in their mothers’ shadows die, then as they rot and decompose, their mother will gobble them up, too.

She divides the cupcakes between us so that we each get to frost six. Then she says, “What do you think? Two for me and five for each of you?”

Sam’s eyes widen. He slides five of the six cupcakes he frosted closer to his chest.

I locate the dingy blue oven mitts still in the drawer next to the oven, yet another thing Mom left behind.

As Jody and Sam lift frosted cupcakes to their mouths and bite, I drop those old mitts into the kitchen wastebasket with the brittle shards of cracked eggshells.

by K.B. Carle | Feb 4, 2021 | news

The Tortoise and the Hare. The Ants nod the Grasshopper. Both are examples of famous fables with the inclusion of animals and a moral. Can a fable be so clearly defined? Is the formula simply animals + a number ![]() 1,000 words x morals = flash fable? I believe what sets a fable apart from any other story (in this case a fairy tale or Ghost story) is the moral. However, not all fables have to include animals although, as an animal lover, I’m not against their inclusion.

1,000 words x morals = flash fable? I believe what sets a fable apart from any other story (in this case a fairy tale or Ghost story) is the moral. However, not all fables have to include animals although, as an animal lover, I’m not against their inclusion.

The following stories are what I consider to be fables and, as you continue preparing your flash fables for Fractured Lit’s Ghost, Fable, and Fractured Fairy tales contest, dare to experiment or re-imagine the definition of a fable. For example, a ghost fable in which the Tortoise and the Hare have a rematch years after their initial race in the spirit world. What if the Pea from The Princess and the Pea is the one who desires to marry the princess or the prince, triggering a whole new story. I wonder what the moral of that Fairy tale fable would be?

- Tiger Free Days by DeMisty D. Bellinger

On the surface, this micro describes the reactions of those observing an escaped tiger pacing outside of their office building. What strikes me about Bellinger’s story is the dialogue, what’s said and unsaid, especially in regards to one character’s impatience to be rid of—what she perceives and what society tells her to believe is—a dangerous animal. The narrator’s reaction, their dialogue suggesting a note of irritation, followed by the narrator walking away from the window is what fascinates me about this piece. I’ve returned to this moment time and time again with new revelations about what this moment could mean for the narrator and how it impacts the story. I re-read this micro several times after the murder of George Floyd and again after the murder of Elijah McClain. Both men, like Bellinger’s tiger, were perceived as dangerous because of their appearance. Both men were faced with the impatience of outsiders eager and ready to be rid of them. I find many morals within Bellinger’s story regarding the impact of silence and assumption as well as the resounding impact of the decision to be an observer behind the glass.

Remember: a fable doesn’t have to fit the formula of animals + a number ![]() 1,000 words x morals = flash fable. Hoang dives directly into the elements of a classic fairy tale, giving us royalty, a kingdom, and a handsome prince. I was immediately struck by this flash because, instead of the wicked stepmother, we are introduced to two very shallow parents with a “not exactly pretty” princess. Hoang’s narrator tells a quirky fairy tale that leads to a very important lesson for the King and Queen. Sure, we receive an assumed happily ever after however, the author takes this fairy tale fable in a darker direction, leading readers to wonder if the King and Queen learned their lesson along with the audience?

1,000 words x morals = flash fable. Hoang dives directly into the elements of a classic fairy tale, giving us royalty, a kingdom, and a handsome prince. I was immediately struck by this flash because, instead of the wicked stepmother, we are introduced to two very shallow parents with a “not exactly pretty” princess. Hoang’s narrator tells a quirky fairy tale that leads to a very important lesson for the King and Queen. Sure, we receive an assumed happily ever after however, the author takes this fairy tale fable in a darker direction, leading readers to wonder if the King and Queen learned their lesson along with the audience?

Not all fables have to include animals however, I do love any writer that can incorporate any animals’ natural instincts to heighten the whimsy in an otherwise serious story. Although Prescott’s main characters are Dung Beetles, we are introduced to some very familiar themes including jealousy, love, and all the complicated conflicts that arise when these two warring emotions come together. I won’t spoil the plot of this flash however, Prescott’s piece is a prime example of a classic fable where animals—instincts and all—are utilized to breathe new life into an otherwise natural occurrence in human life, making this flash unique to Prescott and her Dung Beetle stars.

I was introduced to the work of Ji Yun by the wonderful writer, K.C. Mead-Brewer, and I can’t get enough! This fable includes an element that I have yet to explore but consider to be another category of a fable: a legend. Yun’s flash is a story within a story, one the narrator heard from their servant and is now sharing with us. Why? This is how stories originated. We passed them down so they could be shared, transformed, and remembered. Yun’s legendary fable focuses on the need to continue the generational line but also the treatment of women as meat. While many fables resist the urge to state the moral of the story at the end, Yun does which made me question why? After reading his biography, I learned that he rebelled against his role of censoring texts that were against the emperor’s ideals. Perhaps revealing the moral in his legendary fable is another act of rebellion, a moral within a moral.

Further Reading:

- Slope of Tigers by Ji Yun. Translated by John Yu Branscum and Yi Izzy Yu

- The Listening Tree by Micah Dean Hicks

- Don’s Volcano by Lincoln Michel

- Tales of the Devil’s Wife: Our Children by Carmen Lau

- This is a Story About a Fox by K.B. Carle

by Veronica Montes | Feb 1, 2021 | flash fiction

Behind the books on her shelves she finds the artifacts of their girlhood, all of them fuzzed with dust: pocket-sized dolls with safety-scissor haircuts, crayon stubs, origami frogs, magnetic letters. She frowns when she finds the Tagalog flashcards, a reminder of all the things she failed to teach them: nanay is mother, kanin is rice. She places the items in a basket, sneezing as she goes, and carries them to the dining room.

Her husband has been chiding her for years now to choose a new table; this one still bears evidence of glitter wars and errant markers. In an uncharacteristic burst of frivolity, he has purchased a vintage bar cart and, if delivery tracking is to be trusted, it will arrive in three weeks. He has forced her hand, yes, but she tries one last thing. She says, “The juxtaposition of this glittered farm table and a 1920s bar cart would be interesting, don’t you think?” He shakes his head no, but he does it kindly.

She places one of the ugly-hair dolls in the center of the table, and straightens its checkered dress while she wonders what to do next. On the nights she can’t sleep she ticks off the last time she spoke to each of her three girls, and the last time they visited. She does it now, recites her litany in a whisper like it’s a secret. Last Monday, two Thursdays ago, thirty-six hours or so. Two weeks, one month, ten days. She stares at the doll. And then, even though she really should get started on dinner, she begins to peel the paper off each crayon, she reads and re-folds the notes from summer camp, she groups blocks by shape and color. Around and around the table she goes, moving slowly, humming, setting one thing here, one thing there, arranging and rearranging until her project reaches what feels like its natural end. It’s not quite symmetrical, not quite a mandala, but it’s beautiful in its own way. She stands on a chair and uses her phone to take a photo from above. And another and another.

She senses that her husband is wondering why there are no smells emanating from the kitchen, no garlic, no onions. She sits down anyway and crops her photos. She runs them through a dozen filters, but decides they look better without. She chooses the one she likes best, changes her mind, chooses another. And then, finally, she sends her favorite to the group chat their daughters have set up. At bedtime, she’ll slide her phone under her pillow, and just past midnight, it will start to vibrate every few minutes. She’ll read their messages in the morning, first thing.

by K.B. Carle | Jan 30, 2021 | news

The New Oxford Dictionary defines a fairy tale as a children’s story that includes magical beings and places. I was pleasantly surprised to find the words, “happily ever after,” omitted from the above definition. In my search for fairy tales, the stories I enjoyed most exchanged their happy endings for humorous blunders or darker themes commonly erased to fit into the “children’s story” category. As you finalize your fairy tales for Fractured Lit’s Ghost, Fable, and Fractured Fairy tales contest, I encourage you to pay close attention to character. What happens to all those minor characters after happily ever after? Consider re-imagining the circumstances of your characters and their surroundings. Dare to create a new kind of fairy tale and ask yourself is the dark forest really as evil as it seems? Does Prince Charming always have to be male or, my favorite, what if? The following stories were written by authors who asked themselves: what if?

- Fairy Godmother Protocols by Sarina Dorie

When I hear the words, “fairy tale,” Sarina Dorie’s flash is the first story that tickles my mind. Dorie utilizes the listicle form—a contract between fairy godmother and godchild—thrusting readers into a corporate oriented fairy tale, but we are receiving information from a character who is bibbidi-bobbidi there then salagadoo-gone. This playful flash also provides readers with a wonderful twist in the forbidden romance and who Prince Charming might have had his eyes on the whole time.

Who says fairy tales have to be The Brothers Grimm or Disney inspired? No one, but be ready to protect your chompers from this scorned fairy. Norman takes one of the most controversial imaginations from childhood and provides an answer to the age old question: What does the tooth fairy do with all those teeth? What I’m drawn to most in Norman’s micro is the voice he’s given to his tooth fairy. A tooth burglary gone wrong, clipped wings, children trying to cut a deal in exchange for teeth? That’s my kind of fairy tale!

Not all fairy tales include fairies. McMahon takes a different route, drawing attention to the familiar setting of the mystical—oftentimes dark—forest. However, there are no singing or shrieking—looking at you Snow White—princesses here. This is a story about transformation. A fairy tale exploring the cost of magic, but the source of tension is not in figuring out why, but how to adapt, to learn, and whether to trust everything that comes with this newfound knowledge.

I’m always searching for stories that add a little quirk to the common tropes we find in fairy tales: damsels trapped in towers, true love’s first kiss, wicked stepmothers or dead mothers. Chan shatters several sunny days in a land far, far away where everyone suddenly knows all the words to the same song in exchange for a darker-toned fairy tale with echoes of a Brother’s Grimm original. There is love but also pain within that love. The transformation in this story is not depicted as beautiful, but within the descriptions of binding sealskin to “our” skin, we learn and are exposed to so much more than happily ever after.

One of the most challenging endeavors to embark upon when writing a fairy tale is to re-imagine one. Something must shift within an already established character to set them apart from the original story. Rosso accomplishes this feat with her portrayal of Rapunzel. Although Rapunzel is still trapped in a tower, she’s not a bubbly artist (Disney) or eager to run off with a prince as a means of escape (Into the Woods) but rather eager to free herself from…I won’t spoil this story’s plot for you. What keeps me coming back to this re-imagined feminist fairy tale are the dysfunctional relationships Rosso builds between the familiar cast of characters paired with Rapunzel’s desire to escape from a twist in the narrative that solidifies this as a Christina Rosso fairy tale.

Further reading:

- All for Tulips by Cheryl Pappas

- Rapunzel, Let Down Your by Faye Brinsmead

- Waking Beauty by Stephanie Hutton

- She is a Beast by Christina Rosso

- When Alice Became the Rabbit by Cyndi MacMillan

- Gretl at Hansel’s Deathbed by Kimberly Glanzmen

- Coven by Anna Cabe

- Fairy Tale in Which You Date the Morally Ambiguous Boy in Math by Charlotte Hughes

by Melissa Ostrom | Jan 28, 2021 | micro

The top drawer of the old bureau painted to look new held thirty-six onesies, freshly laundered and folded into tiny squares and arranged just so, like a box of strawberry fudge. The highchair Meryl’s coworkers at the diner had pitched in to buy stood like an empty throne at the end of the kitchen table. And the snow fell slightly, so scarcely, so finely, that it seemed unintentional, unremarkable. An accident. As if the sky had made a mistake.

On the day Meryl turned unpregnant, her body didn’t keep up with the news, and her breasts stayed veined and tender, and her hair stayed glossy and thick, and her feet stayed aching and swollen. Her stomach remained round. Her brain repeated no.

On the day Meryl wasn’t pregnant anymore, she sat in the rocking chair and didn’t cull a creak from the wood or tap the floor to the rhythm of a rock-a-bye baby falling, failing, and a sunshine taken away, please don’t. She didn’t hum and rehearse. She didn’t rock, rock, rock the depleted ocean inside her.

She sat still and stared out the window, wondering how it could be that cars still sped down the street and people still smiled at their phones and the brick building across from hers still shone pinkly in the February light and Mia and Noah in the apartment below hers still made noisy love because it was Tuesday afternoon and on Tuesdays, they both worked from home, while their kids were at school. Tucked into classrooms. Learning, struggling, playing. Growing.

On this day that came too many weeks too soon, Meryl wondered about Mia and Noah’s kids. All three of them, three whole children, among other parents’ children, hundreds, thousands, millions more.

Small humans everywhere. But here.

Recent Comments