by Veronica Montes | May 11, 2021 | interview

Fractured: What excites you about writing flash fiction/ Are there any limitations to the form?

Montes: For me, flash is often about exploring life’s small moments, times when not much seems to be happening, and yet…everything is happening. And so I’m excited by the challenge of trying to give these moments the attention they deserve. By this I mean a beginning, middle, and end, a sense of before and after, whole characters, and a touch of lyricism. The challenge of trying to achieve all of this in under 1,000 words is what I find exciting about writing flash.

As for limitations…what are those?! My fellow flash writers are dazzling me with their experiments and derring-do. While I have yet to push the limits in my own work, they’re providing plenty of inspiration.

Fractured: What normally comes first in your writing process? Image, language, a voice? Titles or a first line?

Montes: My process almost always starts with a snapshot-like image. And then I try to puzzle out why the image came to me or sticks with me. Why these deer feeding from an apple tree? Who is this woman sitting in the dirt? Where is this little boy going, all alone, with that look on his face? Despite my mother hissing, “Veronica stop staring,” into my ear while growing up I have remained, like most writers, extraordinarily nosey (though perhaps more discreet now). One of my favorite things is to observe someone while my train is pulling away, and they’re waiting on the platform. Once on a snowy day in Virginia, I saw a man in a work jumpsuit sitting on the ground with his lunch box beside him, and he was just so weary. This was probably twenty-five years ago, and I’m still waiting to put him in a story. Said story will also feature…soup. I think.

Fractured: I’m in love with cover art/ How do you think it helps contribute to the themes of the book? What was the process like working with Black Lawrence press?

Montes: I love my chapbook cover art, too! Black Lawrence Press was very open to input, so I did what I did for my full-length collection: turned to the Filipino/American Artist Directory. As soon as I saw Mary Jhun’s work, I knew I’d found the right artist. I felt like this painting, “The Young House,” spoke to the rich interior lives of my characters, of their attempts to speak and be heard, of both triumph and failure. Black Lawrence Press is terrific: they have an author handbook to walk you through the entire publication process, and they offer a pre-sale incentive program, plus plenty of support for readings, reviews, etc.

Fractured: How did you decide which stories made it into the chapbook?

Montes: I wanted to create a timeline of sorts, so I chose pieces that told the story of a woman at eight different points in her life (alternately, they can be read as stories about eight different women), from adolescence to elder status. The stories are similar in tone, and they’re all flash, so I wanted to include one piece that was longer (in this case, just under 1,000 words) and had—to me, at least—a completely different feel while still keeping with the themes. I placed that one in the middle and called it an interlude.

Fractured: A lot of these stories feel like allegories. Is that something you focus on when writing/ Is allegory another way of conceiving fairy tales? How did you make these stories so personal, so active?

Montes: I’m asked this question a lot, and I’ve never answered it to my satisfaction. So once more unto the breach: I wish I could be the kind of writer who understands what they’re doing while they’re doing it, but I’m just not. I’ve only consciously written a fairytale once (it’s not even finished; I’ve been writing it for years!), yet many of my stories end up, more or less, in that space. I just write what comes to me without trying to force anything, which is how I think I often end up in a dreamy kind of place. When editing, I look for the point in the story that makes me the most scared or uncomfortable, and then I drill down a little. It’s kind of like pressing on a bruise. Maybe this is what you’re sensing as personal?

Fractured: I love how evocative your titles are, how they are rarely one word! Do titles come naturally to you?

Montes: Thank you! As flash writers we’re hyper-aware of every word, image, and a bit of dialogue; most of it has to do double-duty. So I think flash titles should work just as hard! I find that my titles are often a piece of information that I wasn’t able to include in the text itself or, more generally, an attempt at additional clarification. For example, I wrote a flash that was a little confusing because it featured four characters, but was only 240 words. It received a few good rejections before I realized that the title was contributing nothing—less than nothing, to be honest—to the piece. I changed it to clarify the cast of characters, and it was picked up the next time out by a publication I’d never been brave enough to submit to before. If anyone is curious: “The Alchemist, His Daughter, Their Two Servants” in Wigleaf.

Fractured: What are you waiting for? What would end your waiting?

Montes: There are so many ways to answer this question in these fraught times, but I’m going with the eradication of margins. I’m waiting for zero margins, and I think the end of white supremacy will be the beginning of the end of my waiting.

by Fractured Lit | May 10, 2021 | contests

fractured lit anthology 1 prize

judged by Kathy Fish

CLOSED April 19, 2021

Add to Calendar

submit

2021 Winners:

Night Vision by Anna Gates Ha

(Don’t) Remember Me Like This by Cyn Nooney

Girl on the Bike, Boy in Dayton by John Bensink

Girl in the Snow by Wendy Oleson

I Chose the Pencil by Richard Schwarzenberger

Sweets from Strangers by Tian Yi

We Don’t Boil Babies by Alicia Dekker

Salt City Runaway by Gillian O’Shaughnessy

In Andromeda by Jonathan Cardew

Evening Clay by Josh Wagner

As Solid as an Ashtray and Emits More Smoke by Edie Meade

Grandma Kim at Forty-Five by Chloe Seim

Muscle and Might by Bob Thurber

Mi Porvenir by A.J. Rodriguez

Rabbit, Rabbit by Sally Toner

Account for What You Have by Alexandra Blogier

Marriage Market by Susan Wigmore

If This Were Tracy Island by Marissa Hoffmann

Oil Drills by Lauren Weber

Thursday Night at Lucky’s Liquor Store by Shareen Murayama

Shortlist:

Henrietta by Kim Magowan

Wild Jill’s Bangin’ Karaoke Bar by Kayla Upadhyaya

Animals by Catherine Bush

Love, Exactly by Nikki HoSang

Buen Provecho by Amina Gautier

Waste Meadow by Greg Schutz

Harvest Moon by Kristin Saetveit

Little Tin Box by Jessica Daugherty

Make Dust Our Paper by Bill Merklee

Rustic Haircuts for Returning Ghosts by Nicole Tsuno

Almost Like a Heart by Jason Jackson

Freshman by Allison Renner

Blueberries by Adrienne Barrios

Lace in Your Hands by Lydia Copeland Gwyn

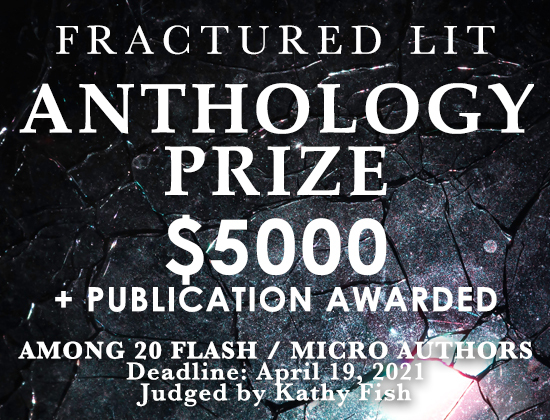

We invite writers to submit to the Fractured Lit Anthology 1 Prize from February 19 to April 19, 2021. Guest judge Kathy Fish will choose 20 prize winners from a shortlist. We’re excited to offer the 20 winners of this prize $250, publication, and 5 contributor copies of the printed anthology. All entries will be considered for publication.

Kathy Fish has published five collections of short fiction, most recently Wild Life: Collected Works from 2003-2018. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Ploughshares, Copper Nickel, Washington Square Review, and numerous other journals, textbooks, and anthologies. Fish’s “Collective Nouns for Humans in the Wild,” was selected for Best American Nonrequired Reading 2018 and the current edition of The Norton Reader. Her newsletter, The Art of Flash Fiction, provides monthly craft articles and writing prompts and is free to all. Subscribe here: https://artofflashfiction.substack.com.

Fractured Lit is looking for flash fiction that lingers long past the first reading. We’re searching for flash that investigates the mysteries of being human, the sorrow, and the joy of connecting to the diverse population around us. We want the stories that explode vertically, the flash that leaves the conventional and the clichéd far behind. Fractured Lit is a flash fiction–centered place for all writers of any background and experience.

Good luck and happy writing!

- Your $20 reading fee allows up to two stories of 1,000 words or fewer each per entry. If submitting two stories, please put them both in a SINGLE document.

- We allow multiple submissions. Each set of two flash stories should have a separate submission accompanied by a reading fee.

- Flash Fiction only. 1,000 word count per individual story is the maximum amount of words.

- We only consider unpublished work for contests. We do not review reprints, including self-published work.

- Simultaneous submissions are okay. Please notify us and withdraw your entry if you find another home for your writing.

- All entries will also be considered for publication in Fractured Lit.

- Double-space your submission and use Times New Roman 12 pt font.

- Please include a brief cover letter with your publication history (if applicable).

- International submissions are welcome, but we only read work in English.

- We do not read blind. The judge will read anonymously from the shortlist.

submit

by Sara Hills | May 10, 2021 | micro

1.

It’s always night when they wheel us girls in, gowned on gurneys. Underground. They pull their masks up and peer at our faces. Line us in rows along the dark gray walls. We must be sick. They must be healers. Lightbulbs swing from the ceiling. Somewhere down the row is Sissy. It’s her turn, and she’s crying.

2.

I refuse to count backwards because I know I’ll die. The blue-scrubbed surgeon reveals the silver-sharp instruments on the tray, filed in order of shine. He swivels smiling on the stool and asks why I’m afraid, sweeping wide with his large hands. Dark hairs prickle his arms like an animal. Each finger wears a tuft of wool.

3.

Bruises lily-pad down my spine. If I were a little frog, I could jump-jump across them, to my arm, my ass, my thighs, where the bruise is—the bruises—are clustery, both dark and bright, big as a man’s hands. Turn, they say, snapping the camera, trapping each one on film. Readying them for the exhibition. Turn, they say. Don’t look away. Drop the sheet a little lower.

4.

The woman assigned to my case has the face of a young Stockard Channing. I expect her to sing, joke, light a cigarette. We sit in her office and read the judgments, the confessions, the lies. Shapes and voices float in and out. A faceful of wet grass, a kneeful of dirty carpet. I roll into a ball. Squeeze myself as small as the head of a pin. The papers wobble in the woman’s hands and grow wet.

5.

With one gloved hand in my cunt, the midwife tells me to push. She tells me my body isn’t working, the baby isn’t breathing, the car is warming up. I float above the bed, above the dark paneled wainscot, above myself. I am the ceiling. I am the yellowed flowers on the walls. Not the blood and the twisted cord and the oxygen tank, the baby girl suctioned and swaddled. Not the panic passing in the doorway. The car is warm, and they know we are coming.

by Fractured Lit | May 7, 2021 | flash fiction, news

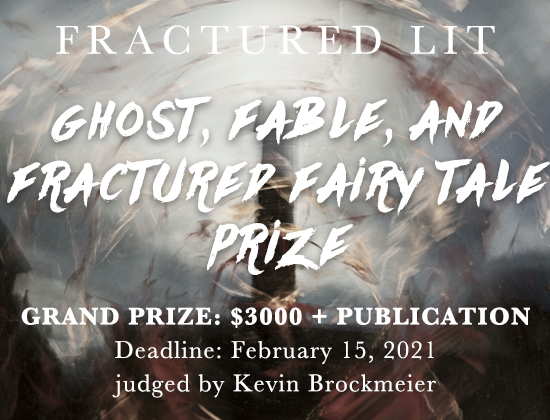

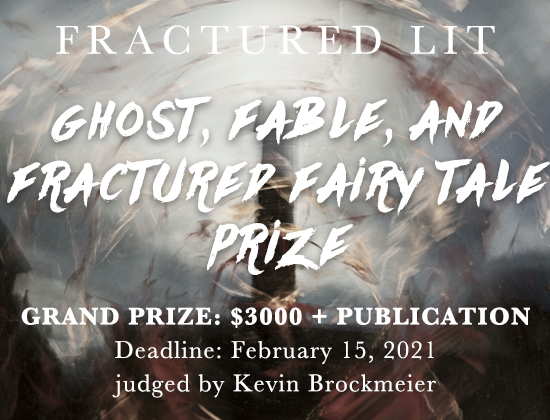

We’re proud to announce the 23 titles of our shortlist! The submissions we received were so thrilling, inventive, and affecting that we’ve had a hard time narrowing down the list! From this list, judge Kevin Brockmeier has chosen his final 3 winners and 2 honorable mentions! Winners will be announced early next week!

A Guide to Small Town Ghosts Regan Puckett

The Better to See D.E. Hardy

This Is How You Become a Myth Ophelia Hu Kinney

El Triste Eric Scot Tryon

The Changeling Sarah Boudreau

The sixth-eldest dancing princess looks back at her legacy Madeline Anthes

The Bone Child Meagan Johanson

Recorded Live dm armstrong

Nosebleed Weather Marilyn Hope

A Too Small Room Yume Kitasei

The Sea Witch Lindsey Kirchoff

Springriven Olivia Frost

The Day The Moon Fell Iona Rule

Scratchers Corey Farrenkopf

Bitter Doll Susan Power

Bloodcoat Carolyne Topdjian

Shame Street Anne Perez

The Eaves Audrey Burges

Dialogue Between a Woman and Her Ba Faye Brinsmead

Ornithology for Girls Tara Stillions Whitehead

Women’s Work Carolyn Jack

His Mother’s Teeth KC Mead-Brewer

god at the side of the road A Poythress

by Yunya Yang | May 7, 2021 | flash fiction

Years ago, his mother brought home a rabbit.

“Make it fat, will you?” she asked him.

The boy held the shivering rabbit in his arms, wrapped it in his coat, folded its body into his, feeling the weak tremble next to his heart. It was spotlessly white like fresh snow.

On his way back from school every day, he collected weeds from the side of the streets. It ate them quietly, with a quivering mouth. Sometimes the boy could catch a glimpse of those big front teeth chewing on the green.

It never made much sound, which the boy liked.

***

One day, when the boy came home, his mother had made soup.

“Eat up. It’s good for you.” She filled the boy’s bowl with meat and broth.

The meat was tender, falling off the bone.

“Fatty, isn’t it?”

The boy paused and looked at his mother, then stared at the soup. Chunks of pink meat floated in it. He thought of the warm, mute snowball against his chest.

“You already had two bowls. Wasn’t it good?”

Yes. It was good. The boy thought he’d be sick, but he only felt full.

***

His father’s new wife had a small daughter. She didn’t like it whenever the boy went to their home.

“My dad hates you,” she told him. “Both you and your mama.”

She loved wearing a puffy white dress, with a white hair thing on her head. She had a wide gap between her front teeth.

“Take your sister to play, will you?” his father asked while playing mahjong.

They played badminton at the empty lot next to the apartment. There was a bicycle shed by the lot, about two-story high. Every time the bird went on top of the shed, the boy climbed up to get it.

“I want to go up this time,” the daughter said after the bird went up again.

“It’s dangerous.”

“I don’t care. I’m going.”

She climbed up.

He didn’t know she’d fall. It was her own fault, of course. He told her it was dangerous.

She hurt her head, the boy heard, never quite the same. His father didn’t let him see her again.

***

A matchmaker once introduced a vegetarian woman to him. She wore a string of sandalwood Buddha beads around her wrist. When she talked, she fiddled with them nonstop.

She asked him if he’d ever thought about giving up meat. He told her it was too hard.

***

Sometimes he feels guilty about the loosened step on top of the bicycle shed. But it never lasts long.

by Fractured Lit | May 4, 2021 | flash fiction, news

We’re proud to announce the 57 titles of our longlist! The submissions we received were so thrilling, inventive, and affecting that we’ve had a hard time narrowing down the list! From this list, 20-25 stories will make it to the shortlist for judge Kevin Brockmeier to choose his final 3 winners and 2 honorable mentions! Please don’t identify your story title as the shortlist will be delivered to Kevin anonymously!

A Guide to Small Town Ghosts

The Better to See

Ghosts in Towers

The Only Problem

This Is How You Become a Myth

Sinta

El Triste

The Changeling

The Fischers

In Her Own Darkness

The sixth-eldest dancing princess looks back at her legacy

The Good Wife

The Meal

The Bone Child

Recorded Live

Nosebleed Weather

A Too Small Room

The Sea Witch

Marjorie

Mortimer

Springriven

Refrigerator Death

A Home With You In It

The Day The Moon Fell

Midnight

Into the Wild

The Fisherwoman

Mother

1,000 Words on Leftovers

Unsure by Faces

Scratchers

Boiling Point

Shimmer

Bitter Doll

Funeral Party

The Last Days of the Henry Doorly Zoo

Bardo

The Moon That You Wait For By Standing

Bloodcoat

He Becomes the Wind

Griselda

Shame Street

The Eaves

Dialogue Between a Woman and Her Ba

A Short Story about a Long Time in the Woods; A Short Story about Boxes

White and Wolf

The Mermaid’s Tale

The woodcutter’s daughter

With Appetite

Ornithology for Girls

Women’s Work

Tap-Tap

An Ordinary Wife

His Mother’s Teeth

god at the side of the road

I Wake with The Cicadas

The Thick Green Ribbon

by Shyla Jones | May 3, 2021 | micro

Every summer, my flower collection expands with my lungs. I gather them before the solstice, because my mother always told me to stock up for winter. She’s a hoarder and has a basement lined with silver cans, the labels old and worn, peeling off like epidermis. My father was a gardener, but he only planted vegetables; he grew them to eat, because all of the whiskey had started to make him think the government watched him through the seeds of a sugar snap pea. Because of the growing black mold in our upstairs bedrooms, my parents and I slept in the living room in sleeping bags and hardened sheets and throw pillows. They never fixed the black mold. They never fixed anything. The vegetables would not save us, so I stole flowers from the world. My father believed the young woman next door poisoned our walls with witchcraft because of her amethyst necklace and bumper sticker of the Queen of Pentacles. One morning while I plucked cosmos from a private garden, he carved Bible verses into the paint of her car with a sewing needle. I came home with a basket of illegal petals and had to apologize on his behalf until the police got bored of us. My father died of stubbornness. The evening of the fifth anniversary of his death has me sneaking into the garden of an odd couple who make rugs from animal hide. I clip the petals from bushes of roses, magnolias, camellias, and then the butterfly bush in front of an old bank. On an apartment balcony sits a plethora of potted flowers; I climb up the fire escape and clip all of those too. I imagine everyone’s faces when they wake to water their sweet smelling children, only to find that they are gone, snipped down to a nub of roots and soil. I chew the petals for dinner and drink the leaves in hot tea. The velvet tongue of a flower melts in my throat and perennials grow in my chest with each breath. When I die, the posies will sprout from my lips, through the dirt of my tomb and across the earth.

by Deirdre Danklin | Apr 30, 2021 | news

The Children of Flash

I don’t like novels told from the perspective of children – they make me uncomfortable. I used to think my distaste was for their naivete or the either overly-precocious or under-developed voice adults use when they’re trying to sound young. Now, I think what I really don’t like is a child’s vulnerability. Things happen to children, they have little agency, and there’s nothing a reader can do to protect a child in a story.

In flash fiction, childhood is a common starting place. A memory can spark a story and can remind the reader of a time when they felt helplessly tied to the whims of the adults in their lives.

In “On “Day Without Name” by Kay Sage” by Nadia Arioli, published in The Whaleroad Review, the childhood memory slices the reader quickly – a stab right back to sitting through Sunday school. The piece begins, “At Bible study, you read about Thomas. The other kids snickered at his unbelief. You thought of his worker hand, gliding into a wound, like a knife into fish.” No phrase makes me more anxious than “the other kids snickered.” There is a culturally-specific vulnerability to this short piece that benefits from being positioned, at first, in childhood. When the piece moves beyond childhood, it says, about Thomas searching the wounds of Christ, “The image lost its resonance over the years,” which is the sort of thing we all think about moments or images from when we were young, that they have faded and we are grown people now, in charge of what we believe and what we do. The pleasantly resonant discomfort of this piece comes from knowing that, far from fading, the things that slice us when we’re children are forever bubbling back up.

This pattern is visible in “The Hills Have Secrets” by Annika Bee, published in Cease, Cows, as well. Once again, the flash is anchored in childhood. It begins, “My uncle used to say that hills held secrets, that hills grew over the Earth specifically to protect those secrets. I grew up in a hilly suburb on Long Island and spent my childhood digging holes in our yard, hoping to unlock their secrets – to my parents’ dismay.” The speaker is forever affected by something her uncle told her when she was a child. Even as the speaker moves on from the hills of her earliest years, her uncle’s words haunt her. Moving next to a canal, she says, “I often wondered what secrets the water held, but the water didn’t hold secrets. It held things.” When the water gives up a bloated, drowned body, the speaker has a shattering moment of nauseous revelation. The “secrets” that sounded enchanting in childhood, the things she dug for and hoped to reveal, can often be upsetting, grotesque, or traumatizing when finally brought to the surface. This is the secret that adults know. The piece, in its forward momentum, leaves the whimsy of childhood behind. The final line says, “Now I leave the hills alone.”

Sometimes, the whimsical beliefs of childhood turn dark. In Jiaqi Kang’s “L’oeil d’Orochimaru” published in Wildness, the characters are vaguely placed in childhood from the perspective of an adult who can’t remember precisely what ages they all were, “We were five and seven and eight and nine, or maybe six and eight and nine and ten, but ten feels too old for Nozomi, or maybe she really was ten at the time.” The children have decided that a tube in a farmer’s field is really a monster requiring sacrifices. They bring it grass and they tell it their most fervent dreams. They are afraid of the tube, and they seem to need it to exert some control over their lives as the children of Japanese expats in French-speaking Switzerland. The speaker of this piece says, “I said that all of these prayers were little practice ones, to help Orochimaru get used to the lilting tones of our French, and one day l’oeil d’Orochimaru would blink and that would mean he was awake and ready to acquiesce, and we had to be ready with the most sincere wishes of our hearts.” This game seems like practice for power and control and agency and manipulation. Children practicing for the darker and more dramatic aspects of adult life, while still waiting for a greater power to grant or deny their wishes. Unique to the stories under discussion, “L’oeil d’Orochimaru” ends in childhood. However, the voice makes it clear that the speaker is an adult now, looking back on the events of the story, somewhat bemused by the intensity with which she enacted these childhood rituals – rituals I recognize from my own days on playgrounds, clutching wildflowers ripped from the ground.

Maybe this familiarity is what makes me squirm when a novel’s voice is a child’s voice. Maybe it reminds me too much of wanting desperately to be old enough to control something. What an adult also knows when faced with these fierce children, is that getting older is no guarantee of control. Part of the poignancy of a child’s voice in fiction is the disparity between what we thought adult life would be like and how it actually is. In flash fiction, I have no trouble with the child’s perspective. I think it can add an off-kilter magical reality to a short piece. The children of flash are rarely precious, and they always have something to say to the children that the readers used to be.

Links to the stories:

“The Hills Have Secrets”

by Minyoung Lee | Apr 29, 2021 | micro

There was once a girl who’d text a boy: I caught a dream on my way home last night.

And the boy would text the girl: I can’t wait to see it.

The girl would see an orange butterfly with clusters of green and gold. She’d text the boy her recollection, translated carefully into pixels.

And the boy would text the girl: She’s beautiful like you.

The girl would read the text and think, “He’s thinking of me, too.”

At each beautiful moment, the girl texted the boy to share.

And though the boy lived far away, he texted her right back every time. He seemed to wait by the phone for her.

Come home soon. What’s for dinner? I can’t wait to see you again.

That’s what the girl saw in her mind.

Until one day, the girl texted the boy and he never texted back.

What the girl didn’t know was that whenever she texted the boy, she’d sent him a bit of her memory. She didn’t know memories were the bits that made up a soul, made up her soul. She didn’t know that bit by bit, byte by byte, the snippets of her soul that witnessed beauty were sent forever to the boy. So, she kept texting and texting even though the boy never returned any of his soul. Through the cellular network’s waves, her very particles evaporated into air.

The girl texted until there was nothing left of her but a rose bush in front of her home.

One day, the boy came to see the girl, but could not see the girl was home. All he could see were luscious roses glistening in the yard. The boy was overwhelmed by the rose’s luster, the scent that filled his hair. He came back day after day to care for the rose bush, to care for the growing beauty. The roses thrived under the boy’s care, her blossoms were bountiful, petals sleek.

The boy grew and became a man. He left the rose bush and the town behind. The rose bush grew too even though he was away.

The man fell in love with a woman. He brought her home to show her his rose bush, his pride and joy, the thing he watered and pruned and protected. The woman fell in love with this man who loved his rose bush and showered love on the thorny plant.

The rose bush, left without memory, could not love. But she seemed to respond to what she felt coming from the man and woman by sending out her fragrance.

On their wedding day, the man crowned the woman with his roses. He loved seeing them in her hair. The rose, shriveled, still waited for his words, the words she’d hoped to hear one day.

Till death do us part, he’d say: I do.

by Maria Alejandra Barrios | Apr 26, 2021 | flash fiction

I wear my dead sister’s lipstick around the house like Grandma told me to. It leaves my lips dry and the shade doesn’t suit me, it’s purple and dark and velvety, against her golden-brown skin luminous and edgy. On me it looks tired. Most things do. But I wear it anyway to sit in the kitchen while I do the trick that Grandma taught me to stir the soup with my mind. Grandma was a witch. She turned the neighbour’s hair red, one hair at a time. The neighbour didn’t notice at first, but she started to see it around the house and she even started thinking her husband was having an affair. One, two, three red hairs in the drain. Soon, all her hair was red like the autumn leaves.

When my sister died, Grandma gave me a bag with all her clothes. She told me to wear them often and with oomph, like my sister would have. She assured me her scent of sweet candied apples and vanilla cloves would lead her back home. But I never see her. Most days, I imagine her perky voice on the phone when she was still alive and still loved me: “Sis, you are always busy. You never have time for me, your lazy sister who lives at home with Grandma.” and I would laugh and tell her not to be silly. She would find her own way. But back then, all she wanted was to be with the baker’s son who couldn’t bake baguettes. And I, with nothing else to do when I went home to visit, would sneak out with him to throw rocks at the shore late at night, drinking mezcal and keeping the neighborhood cats company. He was the only man my sister ever loved because she liked the way he pronounced words with a vaguely French accent. And she liked how his hazel hair was always too long on the sides while sitting heavily on the top. She liked his knitted sweaters too and she liked how they always smelled musky, sparingly washed. Sis never forgave me and she never figured out a way to move out of Grandma’s house, she died, and Grandma, not ready to live without her, followed.

And now it is only me, who came back home to try and sell the house when there was no one around anymore to shut my computer down and tell me, “enough, silly girl, sit here and eat some cinnamon cookies while they are still warm.” Things never stay warm. Which is why, in this empty home I wear her cheap purple lipstick and sing the song that Grandma taught me to sing to turn on the heater using only my words.

The house feels warm and inviting now, and the leaves are changing. They both loved the golden light and crunchy apples, and although I don’t know how to bake a pie they would like, I close my eyes like Grandma taught me and say the words that open her recipe book and flip the pages until it lands on Pumpkin Pie. The cupboards open. Flour, sugar, butter, a can of pumpkin and a whisk appear in front of me. I stand up and start to stir. I’m not in the mood for lighting a candle for them in the little altar I built with all their little keychains they liked to collect of places they would visit one day.

Not tonight. Tonight, I am in the mood for eating mediocre pumpkin pie and sitting on the couch while I hear the screaming cats and the serenade that the baker does two doors down, in the hopes I’ll hear how much he’s hurting. Sis, I say just in case she’s listening, I never cared that much about him. I think he stinks. Like dust, cigarettes and cheap whiskey. The kitchen window opens, and the cold breeze makes my chapped, dry face burn. Grandma would know what to do for that. “Sis,” I say, but the wind hits the window and closes it back.

Recent Comments