by Fractured Lit | Nov 3, 2025 | calendar, contests

AWARDING $3,500 + PUBLICATION

JUDGED BY JEMIMAH WEI

July 17 to September 14, 2025

(Closed)

Ready for the opportunity to turn reality on its head? We’re bringing back our Elsewhere Prize! We want those stories that make a mystery out of the ordinary, that make the rational out of the mystical. Play with the edge of genre, but make sure your character is still the star of your story. From July 17 to September 14, 2025, we welcome submissions to the Fractured Lit Elsewhere Prize.

“We are all strangers in a strange land, longing for home, but not quite knowing what or where home is. We glimpse it sometimes in our dreams, or as we turn a corner, and suddenly there is a strange, sweet familiarity that vanishes almost as soon as it comes.”

For this contest, we want writers to show us the forgotten, the hidden, the otherworldly. We want your stories to take us on journeys and adventures in the worlds only you can create; whether you make the familiar strange or the strange familiar, we know you will take us elsewhere. Be our tour guide through reality and beyond.

For this prize, we are accepting micro and flash fiction, so we’re inviting submissions of stories from 100-1,000 words.

We’re thrilled to partner with Guest Judge Jemimah Wei, who will choose three prize winners from a shortlist. We’re excited to offer the winner of this prize $3,000 and publication, while the second- and third-place winners will receive publication and $300 and $200, respectively. All entries will be considered for publication.

Good luck and happy writing!

In flash I seek the crystallized vision of a writer’s imagination — prose that understands intimately the tides of boldness and restraint, that isn’t afraid to venture into uncharted realities, emotions, and psychologies, yet never loses the thread of their story’s heart. Give me hitherto unmapped routes to familiar emotion, sentences that clarify and surprise, and a sense of the writer’s vision within and beyond the story’s limits.

Jemimah Wei was born and raised in Singapore and is now based between Singapore and the United States. She is a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 Honoree, a winner of the William Van Dyke Short Story Prize, and a former Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and a Felipe P. De Alba Fellow at Columbia University. Her highly anticipated debut novel, THE ORIGINAL DAUGHTER, is a Good Morning America Book Club pick, a New York Times Editors’ Pick, and an IndieNext pick. It debuted at #1 on the Straits Times Bestseller list and has been named a best book of Spring 2025 by Harper’s Bazaar, Elle, Vogue, Apple Books, and more. A recipient of awards and fellowships from Singapore’s National Arts Council, Hemingway House, Sewanee Writers’ Conference, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and Writers in Paradise, Jemimah’s writing has appeared in Joyland, Guernica, and Narrative, amongst others. She is presently a senior prose editor at The Massachusetts Review.

The deadline for entry is September 14, 2025. We will announce the shortlist within twelve to fourteen weeks of the contest’s close. All writers will be notified when the results are final.

OPTIONAL EDITORIAL FEEDBACK:

You may choose to receive editorial feedback on your piece. In your cover letter, please let us know which piece you’d like your editor to focus their review on. We will provide a two-page global letter discussing the strengths of the writing and the recommended focus for revision. Our aim is to make our comments actionable and encouraging. These letters are written by editors and staff readers of Fractured Lit. Should your story win, no feedback will be offered, and your fee will be refunded.

by John Hanley | Nov 3, 2025 | flash fiction

God lived in the cheek-pink etching of a china plate, and He was shaped like fire. He roosted in the glass cabinet year-round, but on special occasions like this, Jenna got to bury Him in mashed potatoes and scrape her fork over the bush.

Today was Easter Sunday. She took little bites from the clouds and watched God reveal Himself to her like a kind of puzzle in reverse. A clean plate was a revelation, and she secretly wished for a new one each time: God as a dragon, God as a druid. God as a witch, a wildfire.

“God is everything,” her mom would say. “But not that.”

Jenna was made of two things: hunger and questions. She could get a good meal out of her mother, but never a straight answer.

They’d made a roast chicken for Easter dinner, and Jenna, all but hanging from the oven handle, had watched it cook. Syrupy carrots, wedges of onion, fresh-picked thyme – an altar for the bird. She knelt in front of the little window, under the honey-gold light of the gas flame.

“Ask your dad for the oyster,” her aunt told her. “That’s the best part.”

Her aunt was lighting the Advent candles with a stick lighter. She was a fluorescent but soft-spoken church lady whom Jenna never knew how to talk to. Jenna nodded and turned back to the chicken to look for oysters.

It seemed impossible, but then again, she’d heard somewhere that chickens came from dinosaurs. She wondered which one she was closer to. She wondered what it meant to eat something.

Right before dinner, she took the chicken oyster like communion. It was not a real oyster, but it was just as much like a cube of soft butter. Rich, fatty, luxurious – it shocked her that they would put the body of Jesus in a cracker.

Eat of my body (said Jesus), said the priest that morning, for I have given it up, something, something.

At dinner, Jenna sawed at her chicken breast until her knife slipped and screeched against the man who looked at God. Moses, her mother had told her. Moses Schmoses, she’d thought. He had his back turned anyway. She scratched curiously with her knife to see if she could do any damage, but this was not like the bleacher-seat hieroglyphs in the school gym that could be carved away with a dull pencil.

Her aunt—tangerine skirt suit, earrings like the shell of some ancient bug, a perfume like the time Jenna had asked to sip her father’s brandy and couldn’t get past the smell—was saying something about being thankful for the chicken, and for Jesus.

Today, God emerged from Jenna’s potatoes as a stovetop. The one like her parents’, with the even ring of flame-feathers going blue to orange.

“Moses cooked a chicken on God,” she said aloud, to see which eyes would watch her. “Eat of my body, for I have roasted it for you.”

Her aunt, mid-bite and wide-eyed, ceased her chewing and squirreled it away in her cheek as if she needed that brain power to process.

“God is not a joke,” her father said. His voice was hard, but Jenna saw how he fought to wrangle the corners of his mouth, and reality cracked open to her, just barely.

“He is not!” her mother echoed. Hers was a voice like china, brittle and breakable. “Not on this day.”

With that, her mother wrenched the fork and knife from Jenna’s clenched hands and piled them with her napkin on top of God. It was a signal that Jenna was to leave the table and hide herself.

God is not a witch, a joke, or a chicken. An oyster is not an oyster.

Jenna could not make heads or tails of it. She stood in the kitchen with her plate in her hands. The oven was off, but its light had been left on, painting a slanted square on the tiles. It offended her.

She took her plate to the stove, and with one hand switched off the oven light, then turned the knob for the front left burner until it clicked and God leapt up in soft, even lines. She watched Him flutter against the cast-iron grates. She did the same for every burner, then again for the oven, whose door she left open. She smelled the sparked gas, sweet and sharp, and remembered learning that the fire had to be lit or the house could explode.

Jenna stared until her eyes went dry and sweat sprouted in the creases of her eyelids. The chicken-oyster oil thickened in her mouth. More sweat bloomed on her upper lip. She felt all the water in her body playing musical chairs, and her heart played thumping music.

She’d been a witch for Halloween the year prior, after she’d learned that witches were burned. She asked her mother to cover her in soot and to paint her makeup like peeled skin. Her mother refused and said only that she would rather die.

Jenna took the napkin from her plate. She dangled it over the front burner until it lit. Her parents let out a cackle in the dining room. She let her fingers singe and held them there longer.

God is not a druid or a china plate.

She bolted her hand away and into her mouth, but she knew she had gotten close. She left God burning and returned to the dining room.

Her family waited for an apology to pretend to forgive, and Jenna had one prepared.

“God is not a plate,” she said.

She chucked it down with force, and did not look to see where the etching fissured, because she lunged over it to seize two Advent candles before her mother could take her arms.

Bringing their flames to her cheeks, she felt her eyes make tears and her skin make sweat, as if to fight against the very thing that would turn her into God.

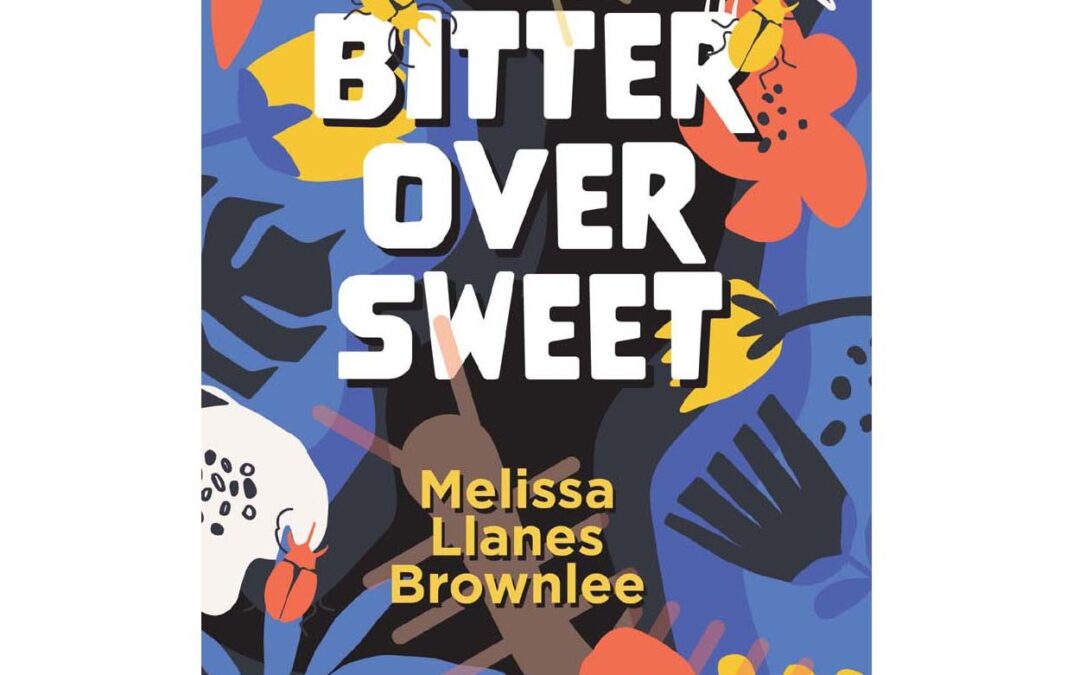

by Fractured Lit | Oct 31, 2025 | interview

by Dawn Tasaka Steffler

Melissa Llanes Brownlee’s Bitter Over Sweet was the 2023 winner of the Santa Fe Writers Project Literary Awards. This accomplishment was huge for Melissa, but also for the Flash community. As she says in this interview, and has mentioned privately amongst friends, she wants the world to know that flash is a form to be reckoned with. So, even if you’ve gobbled up (as I have) every story as it was published in various magazines and journals, in this book those once familiar, stand-alone stories are transformed into a totally different reading experience; leaping past the micro-forms they were born into—similar to how Tita escapes her small life in Hawai’i—and blossoming into their full potential: complex, layered, polyphonic, and absolutely stunning.

Dawn Tasaka Steffler: I absolutely love the title and cover of your book! How did this title come about? And did you have input regarding the cover art?

Melissa Llanes Brownlee: Thanks! My original title was The Lives of Tita. But as my collection expanded, I thought that Bitter over Sweet suited the idea of poverty and paradise, which figures prominently in my book. As for the cover, I had hired an artist, but they were unable to complete the commission, so I sent my ideas of bright colors with Hawaii’s flora and fauna, native and invasive, to my publisher, and they delivered this gorgeous cover. I couldn’t be happier.

DTS: How is it working with Santa Fe Writers Project?

MLB: It’s been eye-opening. As you know, I have two previous books, Hard Skin and Kahi and Lua, both with independent publishers. Each experience was so different, but with SFWP, I feel like I am working with a publisher who is all in on supporting me and helping me, from having the best version of my book to social media promotions, reviews, and getting my book in front of prize committees. I have been beyond grateful for this amazing opportunity.

DTS: What was the writing of this collection like? Did the intention come first of writing a series of stories centered on a particular character? Or did the stories happen organically, and lead you to the realization that you had a collection on your hands?

MLB: Honestly, I just kept circling the same themes, writing the same kinds of stories, over and over, and they naturally lent themselves to a collection with a solid narrative through line. There was no intent behind it. I think that some people can have a goal and write to that goal. I just write and see what comes from it.

DTS: This is a related question: has Tita always been a singular entity in your mind, and if so, who showed up first, older Tita or younger Tita? Or, did they show up as several characters and you gradually winnowed them down to one?

MLB: For me, Tita is just an everygirl. She always has been. Every native girl is both Tita-the sister, and Tita-the negative, derogative, diminutive. Tita is not even a Hawaiian word; it’s Hawaiian Pidgin Creole, so for me, it captures the nature of being Hawaiian but not Hawaiian, the liminal spaces of growing up in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, before the renaissance of our native language.

DTS: You tackle some heavy themes in this book: poverty, domestic abuse, resilience, and hope. Are any of your characters inspired by real people?

MLB: I have lived it. My family has lived it. My friends. The people in my community on the Big Island. The students I went to Kamehameha Schools with. Even though this is fiction, there’s truth in almost every story I have written about living in Hawai’i.

DTS: Tita escapes a dead-end life in Hawaii and ends up in Japan at the end of the book, similar to your own history. And I can’t help but wonder, how has living in Japan influenced the writing of this book? Does living somewhere different afford you some sort of geographic, cultural, or emotional distance? Does it make you miss Hawaii more? Or do you think you understand Hawaii better from afar? Do you think you will ever move back?

MLB: When we decided to go to college (we left Hawai’i in 1999), my husband and I had no idea where our future would be. There was always the idea that we might return, but I think that was always a fantasy. There was and is nothing on the Big Island that we could do to support ourselves in the fields we had chosen. We miss Hawai’i, but it’s the Hawai’i of our youth, our hanabata days, so to speak. I started writing about Hawai’i when I attended Boise State, so I do think that distance did help to see that I was filled with an abundance of stories that I could tell and share, showing people what Hawai’i was really like. Japan just kind of happened because I came here for my MFA program, and when we left grad school, we thought, Why not teach English here?, and we’ve been here ever since. I often wonder what would happen to my writing if I lived in Hawai’i. Would it still be rich, evocative, rooted in truth? I don’t know. Hawai’i is both the same but also different. The landscape for young kanaka maoli is so different now, but the shackles of institutional racism still exist to this day, and this is coming from someone who was able to attend one of the best schools in Hawai’i for Hawaiians.

DTS: In my personal opinion, you are the Queen of Micros. I’d love to know more about how you choose the moments you write about. Is it a matter of intensity, compactness, or maybe it’s a moment of heat you keep obsessing about? Do you have a file of story ideas? Or do your stories just happen organically, without much pre-planning?

MLB: Thank you! All of the above? I don’t plan. I do obsess, but I think that’s most writers. I honestly write small because that’s how much time I usually have to write, or that’s the amount of time that my brain wants to spend writing.

DTS: I think I remember you told me once you don’t revise much. What’s the fastest you’ve ever gone, from drafting to publication?

MLB: Less than one day. Sometimes you write something and you just know… this is the one for this place. It doesn’t happen often because I have been trying over the last few years to send my work to places that usually take much longer to respond because I believe in flash, and I especially believe in microfiction, and I want our writing to be more mainstream.

DTS: What’s next for you? I saw in one of your Talk Story posts that you’re working on a novel?

MLB: I have a Tita becomes Pele novel in the works, but writing that long feels so challenging.

DTS: Is there a question I haven’t asked here that you wish I had?

MLB: Yes! What is your favorite ice cream flavor? And the answer is mint chocolate chip. Always.

(DTS: Mine, too! Baskins and Robbins ftw.)

(MLB: Yes!! Remember when pints were 2 for $5?)

###

Melissa Llanes Brownlee (she/her), a native Hawaiian writer living in Japan, has work forthcoming in Prairie Schooner. Read Hard Skin (2022), Kahi and Lua (2022), and preorder Bitter over Sweet (2025) from Santa Fe Writers Project. Also, register for her online book launch with Deesha Philyaw and Avitus B. Carle on November 7th at 7 pm EST. She tweets @lumchanmfa, plays her ukulele on YouTube (@melissallanesbrownlee) and Instagram (@lumchanmfa / @lumchanukulele), and talks story at melissallanesbrownlee.com.

Dawn Tasaka Steffler is an Asian-American writer from Hawaii who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. She was a Smokelong Quarterly Emerging Writer Fellow, winner of the 2023 Bath Flash Fiction Award, finalist for the 2025 Lascaux Review Prize in Flash Fiction, and selected for Best Small Fictions 2025, and an Anthology of Rural Stories by Writers of Color, 2025 (EastOver Press). Her stories appear in Pithead Chapel, Moon City Review, The Forge, Sundog Lit, and more. Find her online at dawntasakasteffler.com and on BlueSky, Instagram, and Facebook @dawnsteffler.

by Matt Barrett | Oct 30, 2025 | micro

Kathy Morris must have been half-bat, half-opossum because no human could hang upside down for so long and not feel funny about it after. She’d flip herself over the monkey bars and chase us back into school like it was no big deal she’d just hung there with her hair sweeping the woodchips and eyes shut tight like she was sleeping. We called her an oposs-a-bat, which some of us said endearingly and others not so much. Once, two brothers found an opossum behind the dumpsters at 7-Eleven, its mouth frothing and acting strange till their daddy had to come and shoot it. A bat bite, some of us said—don’t you know them things got rabies?—like a handful of fifth graders were suddenly scholars when it came to bats. Maybe they were Kathy’s folks, we said. We didn’t know what things were like in her home. Didn’t know her father had punched a hole in their wall and shattered her mother’s medicine cabinet, or that her mother spent each night behind a closed door that double locked. Kathy just hung there like she always did, never bothering to hear us or open her eyes, not even when word got out and one of us whispered: Maybe it’s your dad we ought to put down. There were plenty of things we didn’t know back then. Like why our clothes never came with tags or what would happen to the dreams we kept. We didn’t mind being dirty. Didn’t mind when our daddies left us, as long as the ones who stayed were worse. In our freshman year, a teacher told us about flying. From the Wright brothers to pterodactyls, from great blue herons to bats. You know why bats hang upside down? she asked. We hadn’t thought of Kathy in three years. Hadn’t said her name since her daddy picked her up one day and never brought her back. ’Cause in order to fly, she said, first they’ve got to fall, and for a moment, we saw Kathy again, hanging from the monkey bars as her daddy came to yank her down, only this time she rose, zigzagging and swooping, beyond his reach and ours.

by Fractured Lit | Oct 28, 2025 | calendar, contests

2025 Writing Micros with Urgency and Immediacy Generative Class

Taught by Tommy Dean

Register from November 01 to December 03, 2025

This opportunity is closed!

Writing Micros with Urgency and Immediacy

Thursday, December 04, 2025, 7-8:30 p.m. EDT 4-5:30 p.m. PDT

Join us for a 90-minute generative writing session focused on writing microfiction! Fractured Lit is excited to bring this class back to our submitters to help them write exciting and fresh micros they can enter into our yearly Micro Prize.

Editor in Chief Tommy Dean has developed an inspiring and welcoming class where participants can learn craft moves from excellent model texts and write to multifaceted writing prompts. Past students have published stories inspired by Tommy’s prompts in today’s best flash fiction literary magazines.

Microfiction demands that the writer (re)consider every word, every craft move, and every design decision. Writing these stories is a challenge, but a fun one! In this class, we’ll focus on stretching our use of writing elements and craft moves to imbue our microfiction with electricity and resonance.

Need a jump-start to your writing, want to try writing with extreme brevity, or just want to spend some time writing?

We hope you’ll come write with us, so we’re offering this class for the low price of $20 per student! All interested are welcome, regardless of experience.

For everyone registering for this class, we’re offering a reduced fee ($12) to enter our Micro Prize! A separate special link will be sent out at the start of the contest to use the reduced entry rate. The Micro Prize opens on December 1st and awards $2,000 to the winner! The judge this year is Steve Almond!

Raffle Opportunity!

For an additional $5, participants can sign up for a raffle, with winners selected in early December.

7 Quick thoughts about Writing Micros

- Even micros need a sense of character, setting, and conflict. Even the weird, the surreal has to take place somewhere, have a driving force, and push toward resonance.

- Point of View: Where’s the camera? Who’s telling the story? What distance in time from the events of the story?

- Micros are grounded in looking at things in new ways, a combination of story and metaphor. Everything has a sense of being more significant than the face value. Don’t be afraid to state a truth, specifically and boldly.

- Embrace Mystery: How much can you leave out? How can you intrigue the reader with clues, details without leaving them cold or confused?

- Story Elements: Use as many or as few as you can get away with to contain the story, stakes, and meaning. How much exposition do you really need? Cut vigorously! Do we need a falling action or even a typical resolution?

- Dichotomies create tension for both the writer and the reader. What pairs of opposites fit in the world of your story?

- End with resonance: There should be stakes for both character and reader! Zoom in, zoom out, whisper, scream, duck a punch, give an uppercut, sound the alarm internally or for the whole world.

Tommy Dean is an associate literary agent with Rosecliff Literary, the author of two flash fiction chapbooks, Special Like the People on TV (Redbird Chapbooks, 2014) and Covenants (ELJ Editions, 2021), and a full flash collection, Hollows (Alternating Current Press, 2022). He lives in Indiana, where he is currently the editor of Fractured Lit and Uncharted Magazine. A recipient of the 2019 Lascaux Prize in Short Fiction, his writing can be found in Best Microfiction 2019, 2020, 2023, and Best Small Fiction 2019 and 2022. His work has been published in Monkeybicycle, Laurel Review, Moon City Review, Pithead Chapel, Harpur Palate, and many other litmags. He has taught writing workshops for the Gotham Writers Workshop, The Writers Center, and The Writers Workshop. Find him at tommydeanwriter.com and on Twitter @TommyDeanWriter.

The deadline to register is December 03, 2025. The class will take place on Thursday, December 04, 2025 at 7-8:30 p.m. EDT 4-5:30 PM PDT

Class Takeaways

By the end of this generative workshop, you’ll have gained:

- Knowledge of or new insight on microfiction-specific craft moves you can use in your writing.

- A new reading list of microfiction examples. Plus, in-depth analysis of the craft moves that lead to excellent short-short stories.

- Four to five new prompts to inspire you to create solid beginnings or endings. Students will also be given a PDF copy of the slides, including the prompts, so they can use them in the future.

- Dedicated writing time in an inclusive community of writers where you can feel welcomed and comfortable sharing your work and ideas.

by Adam Fell | Oct 28, 2025 | contest winner, flash fiction

Overnight, the lake reveals itself.

We wake to the sudden beating of its body against our properties.

The sudden beating. The sudden beating.

At first, we ignore it. We see it but pretend not to. Like we often do with our neighbors. But then our pets begin to disappear. A labradoodle, a ferret, a hedgehog named Egg Nog. From our cars & homes we skip rumors across this sudden water’s face.

Panic ripples.

We gavel the town council to order. We vote to close debate without debating, then gather our rifles & torches at the shore. We throw fire at the water, misfire, throw fire at the water, misfire. Our fingertips ache from the matches burning down. We try again & again, thousands of us, filling the lake with beach sand, shore sod, train tracks & their gravel, shards of bike paths, the ruins of concessions stands, the heavy stones of wavebreaks. We keep filling, keep dredging. We dump parked cars in the lake. We dump the parking meters. We dump the bags of change collected from the parking meters. We dump our credit cards & cake pans & high cholesterol medication. We dump the parking enforcement jeeps, the leftover parking line paint, the cracked orange cones & sand-filled barrels & the wooden police barricades. We toss in the salt trucks & the garbage trucks & fire trucks & ambulances.

Mike says why not the hospital?.

We vote.

The hospital goes into the lake.

Bethany says why not the trees?

We vote.

Into the lake the trees go, into the lake the cliffs go, into the lake the sun seems to go, but we didn’t throw that in, we didn’t even think about that. We know it’s just an illusion. Like the night washing the daylight from the lake’s face & replacing it with its own shimmering emptiness. Which is really an immeasurable fullness. Kyle has an idea: to keep the night to work, we should install floodlights on shore. We vote for floodlights on shore. The floodlights peel open the iridescent grey skin of the lake, the workers, the neighborhoods. We fill & fill & fill the night lake until our muscles ache out of our sweat-stained shirts. We are running out of things, running, running, things, things, but the lake still calmly digests all that we give it. It opens & swallows, opens & swallows. Never a complaint, & as each thing slips beneath the surface, the lake stills, leaving only our own faces staring up at us from the purest mirror water.

Around midnight, we run out of rubble, so we vote to create new rubble from the small businesses of our town. The coffee shop, the ice cream shop, the fudge shop, the muffler shop, the microbrewery, the micropub, the wine bar. We make rubble of the library, the post office, the VFW post, the gas station, the banquet hall, the council chambers. We vote to throw our warm, well-lit homes into the lake. Our warm, well-lit homes go into the lake. We vote to tear down the massive estates. The massive estates go into the lake. The richest of us send their lawyers. The lawyers go into the lake. Along with all the front-end loaders, bulldozers, skid steers, dump trucks, dumpsters, portajohns, floodlights. Then, the shovels & the guns.

Bill says: I wonder if some of us shouldn’t, you know, throw ourselves in as a sacrifice to the cause of wiping out this foreign scourge, this outsider, this sudden attack on our very way of …

Bill goes quiet.

We did not vote for him to go quiet.

He is listening to something beyond us & then we are listening to something beyond us.

A faint voice glimmers across the water. Washes over us. A wave of bloodbright music. We think: where have we heard that before? The lake has always been here. The lake has always been singing.

We call the vote. It is unanimous.

We vote to throw ourselves in. We all volunteer to be martyrs, so we step into the water. But the water will not take us. We stand on the lake, see our faces on its surface flickering in torchlight, moonlight, & realize we go no deeper than that first sheer veil of water, realize we are exactly what stares back at us. We are the invaders. We have inflicted ourselves upon it. By ourselves, by our fear, by our desperate love for what we believed to be true, whether what we believed to be true is actually true or not. Behind us, the missing pets emerge from the trees.

by Aishatu Ado | Oct 27, 2025 | contest winner, flash fiction

We had always been many-in-one, even before witch-woman Nnenka’s curse made it flesh. Our mothers stood at different cooking fires, our fathers prayed to different ancestors, yet destiny pulled us together like scattered beads finding their way back to a single string. In the market square of our village, they still remember how we used to walk, separate—three girls with three shadows and three different laughs. Amara lived half in this world, half in history’s bloodstream, her school notebook margins bloomed with Queen Amina’s battle tales. Zainab danced sufi-spells at cattle camps. Her feet made djinn swallow their thousand tongues and bleed prophecies older than her ancestral bones in Sokoto. And Kioni, keeper of secrets that arrived wrapped in midnight shame, whose garden herb roots knew how to make white man’s seed die screaming before it could grow into tomorrow’s grief.

We were ogbanje before we knew it, before we had names for the thing that made us different, the thing that made the air shimmer around us like heat on tar. That was before witch-woman Nnenka found us counting cowries under the udala tree. She saw rivals who could match her century of keeping white men’s boots from crossing village borders. Her sideways-walking legs brought brass-bell clatter, brought curse born from spite and fear of being outdone.

Now nobody asks why we walk three-heads-one-body down the grass path. Nobody dares. Not since they found the last man who laughed at us split wide like overripe pawpaw at the crossroads, his guts writing prophecies in Nsibidi script older than Lord Lugard Street in Lagos. Witch been dead seven moons but her curse still grips our flesh like lion teeth in midnight meat. White man writes us down in his book under “African Deformity,” but he doesn’t know shit about power this old. Power that was ancient when Oshun was still sucking her mother’s milk.

Three souls crammed in one meat-cage like fish in a trap, three clay pots on three heads, and every morning we fight over who wears the flesh first. Sometimes the argument ends in blood. Sometimes in a song that makes hyenas cover their ears. Sometimes the body rebels, spits out all three souls like bitter kola, leaves us begging proper-proper to come back in.

Amara wants it for fighting, still thinking revolution hides in gun barrels. She forgets the old ways of war—plantain mixed with menstrual blood sweet as first-love’s spit but shadow-blade sharper than co-wife’s tongue. This kind of juju turns a soldier to pillars of salt before his first boot print dries in the dirt.

Zainab wants to dance with it, says visions come clearer when the body moves like cobra-spine. Dance that cracks thick baobab trunks, dance that wakes sleeping Orishas. The kind of dance that makes thunder swallow its own sound.

And Kioni, quiet-quiet Kioni who used to heal with just a touch, she wants to return to the crossroads, thinking maybe the devil-woman who cursed us might still be lurking there, looking to make a bargain. But what deal can you make with a witch who’s already dead?

Each dawn we feel the merging sink into marrow, and often forget to argue at all. That terrifies us more than any witch-mark—losing our separate angers, our different hungers.

Truth strikes deeper than mosquito-thirst: we stronger this way.

When soldier-man comes hunting our village girls, we shift quick-quick between souls until his head spins. One minute we’re in warrior stance, ready to open his belly slow-slow with rust-blade. Next breath we’re the medicine-woman, feeding him his dead mama’s tears till shame drowns his courage. Third turn we’re spirit-walker, showing him seven deaths waiting in his future, each one worse than the last.

Some people think cursing is a simple thing. Put lizard head in someone’s soup, murmur mmuo words. But real curses got layers like iroko tree got rings. First layer: flesh binding to flesh, palm sap thick and unyielding. Second layer: raging thoughts eating memories until even our scars forget which body birthed them. Third layer: power growing in the spaces between souls, strong enough to make even Shango stutter in his thunder-walking.

Night market women say they see us dancing when the moon swells full as a witch’s calabash. Say we fracture into three wraiths but keep one body. Say spirit-forms hunt each other like leopard stalking gazelle—kill-dance, fuck-dance, both the same blood-rhythm. Each shape wearing a face our mothers once named, before witch-woman’s pot boiled us into something new.

Some nights we dream we were one soul all along, split three ways when Olodumare first shaped dawn. Dreams lie though. Taste sweet as rotten mango—sugar on top, maggots beneath. We remember our separate selves clear as machete-light on bone, but memory means nothing when you are becoming something that makes the oldest Gando leak fear from every hole—rank as week-old fish. A thing that trades riddles with river mothers, drinks kunu fermented in grave-soil—thick as clotted blood, sharp with sorghum bite.

Village children sing about us in twilight:

Three heads in morning

One body at noon

No heads in evening

Death coming soon

But death already came and went with harmattan winds. Came when the witch bound us together, went when we transformed confinement into coronation. Now we wait to see what emerges from this chrysalis of flesh, what sublime terror we birth from unified breath.

Let them bring their holy water. Three pots, three souls, one body walking. Every footstep writes juju-law no Imam or Reverend or Babalawo ever learned to read.

They say witch-woman Nnenka died because you can’t bind three spirits stronger than your own. She thought we’d war for the flesh until nothing remained. Last thing she saw was three powers turning her own curse into knives that cut her throat.

They say three girls went missing the same night Nnenka died. Say nobody ever found their bodies.

We not missing. We right here, walking—three-souls-strong—daring anyone to call us cursed.

by Pascha Sotolongo | Oct 20, 2025 | contest winner, flash fiction

Between Abuela’s mobile home and mine, a white sand path interweaves the moonlit scrub pine. Sometimes it is ribboned with the tracks of sidewinders, so we watch our step, especially near the Spanish bayonets beneath which they like to coil. If the snakes have any sense at all, they will stay put tonight. The fantasma rides moonlight like an updraft, talons gleaming, velvety wings combing the air.

The bathtub faucet drips, and my mind travels the sound of it to the dark drain from which crawfish sometimes emerge. Mami’s working the overnight shift at the airport and will come home smelling of hot dogs. Papi’s driving a cab. Except for the dripping, the place is silent. Me, I’m a fifteen-year-old high school dropout with a mind adept at focusing down and down until the only reality is this window where I wait for Ines, my tia, two years older than me and adjudicator of all that is awesome. Where I am naive, the product of strict and overprotective parenting, she is a teen sage, wise to all that’s bad, fine, rad, or elicits her incredulous, Oh right. Here’s how it is: Ines and I can watch the same sad story on TV, and I’ll exclaim, qué lastima! totally meaning it, while she looks on blandly and finally comes out with, Oh, right, and a smirk to remind me I’m a rube.

Any minute now, she will materialize, and I should say a prayer for her safety. Ines fears the night, fears la fantasma more—winged Llorona in love with moonlight. For years, darkness treated my tia cruelly, veiling the sins of a vile father, the man Abuela took up with after she and Abuelo divorced. Now in her bedroom late at night, Ines turns mean, transforms into a girl monster, lowering her voice, curling her thin fingers into claws, lifting her elbows like wings, making her eyes wide and fiendish. At first, I maintain my composure, telling her to stop, sighing. Then terror squeezes my eyes shut and screams out of me. When Abuela demands to know what the hell is going on in there, Ines only laughs.

I have no prayer for Ines.

And here she comes, a dark shape propelled by spindly legs. She looks spooked already, pale face lifted to the sky, then peering down as she dances around ruts and roots, then facing the sky again. The owl has a record, has rushed Ines twice this week. Probably has a nest nearby, Abuela says. I’ve heard it hooting but never seen it. For me, la fantasma lives only in my imagination, where it is something ferocious and beautiful. My breath grows audible against the window, and I use my sleeve to wipe away a coin of vapor. Ines looks almost fragile, like a moon maiden, like a child with dark curls swinging.

People assume we’re sisters, usually that I’m the older one. Abuela likes challenging cashiers and waitresses to guess which of us is her daughter and which her granddaughter. They always guess wrong, and my grandmother laughs at how readily they fall into her little trap. So here comes mi tia who is not mi hermana, the bond between us strong because it’s a blood bond and because when the relationship is good, it’s like stepping out of a cold shadow into the sunlight, goosebumps delicious as love. We understand each other. When no one’s looking, we hold tea parties and pretend we’re English royalty. We drink Materva out of plastic wine glasses and imagine the bubbles have made us drunk. We cut each other’s hair, bleach our Cuban girl mustaches together.

Ines moves quickly, and I start to think she’s in the clear, but a black form wheels out of the silver night and falls upon her, its immense wings indistinguishable from the shadow they cast. Mi tia makes a small sound, almost a whimper, but I hear it because my forehead presses the thin glass. I, too, gasp and feel my shoulders rise as Ines ducks and throws her forearms over her head. In the kind of silence that makes you feel you’ve gone deaf, the owl flaps and lurches so that whichever way Ines thinks to dart, it is already there, charging her.

Ines is no fiend. I see this now and at last send up a gauzy prayer, but it’s too late. The sand, the roots that breach it like the backs of sea monsters, make Ines’s skinny ankles wobble and turn. When she falls, I feel my body lurch—an S snapped into a straight line. I should grab the broom, run to her, save her from la fantasma. I should. But first I watch. First, I count to three.

Uno.

Dos.

Tres.

Ines! I call. I’m coming! Already sand has flooded my flip flops, grinds against my heels and the balls of my feet, slaps my calves as I run. Before me, the owl rises, slips into the moonlight where it glows pale and soft as fog, its yellow eyes watching me, blinking once before it floats away.

One of Ines’s canvas shoes lies on the path that is otherwise empty. I pick it up—too small for me—shake off the sand and walk to Abuela’s trailer. Ines? I call from the porch. Ines? The door is unlocked, and it’s dark inside. Feels like as far as I want to go is the doorway, so I stand there, a velvet painting of Ortiz’s guapo matador on the opposite wall, his sure gaze trained somewhere over my right shoulder. Ines? I call again. No one answers.

From the edge of the porch, I scan the path, the treetops, the sky, the moon so bright I can feel my pupils contract. Ines, I say to the stars, my voice tight, my hands beginning to sweat. Far away, la fantasma snickers, hoo-h’HOO-hoo-hoo.

by Fractured Lit | Oct 20, 2025 | news

This shortlist didn’t come any easier to decide as we received so many great stories with unique premises and characters! There was a great response to this contest, and so many great stories that it took us longer than usual to decide, but we’re excited to share with you the shortlisted titles. We’ll be back with Judge Gwen Kirby’s winners in 4-5 weeks!

Shortlist:

- Body Count

- What Were You Thinking

- The Wreck of the Medusa

- Blackboxing

- The Weight of Jade

- Cat Lady

- A Thousand Ways to Eat a Heart or: Is It Worth Going Inside the Sagrada Familia?

- Meiyue

- Sometimes Grief is a Moonrise

- Three Months After Turning Forty

- Miss Piggy on the Dashboard

- Plaque

- Kismet

- Lessons from Birth

- Advertence

- Cranberry Thyme

- Grooves

- Simulcast

- The Cardinal

- Tiny God

- The Last Wrong Turn

- Every Solid Thing Casts a Shadow

- Fishy Pants

- Dead Mother Card

- I Want That Tomorrow

- The Pitch Perfect

- Pure Trash

- L’Emergency Bars

- With These Wings I Set Thee Free

- Ah Ma is a Reusable Bag

by Fractured Lit | Oct 16, 2025 | news

Writers and Readers! We’ve been spending our time this summer and into the fall reading for this contest, and we’ve finally set our longlist! There was a great response to this contest, and so many great stories that it took us longer than usual, but we’re excited to share with you the longlisted titles. We’ll be back with the shortlist shortly!

Longlist:

- Sweetheart

- Body Count

- The Lost Brother

- My Your Her Boots

- Sunday Nights

- What Were You Thinking

- The Wreck of the Medusa

- The Surrogate

- Blackboxing

- The Weight of Jade

- Cat Lady

- Quills

- A Thousand Ways to Eat a Heart or: Is It Worth Going Inside the Sagrada Familia?

- Meiyue

- Sometimes Grief is a Moonrise

- Three Months After Turning Forty

- Miss Piggy on the Dashboard

- Plaque

- Kismet

- The Red Line at Glòries

- Something They Know

- Lessons from Birth

- What is Home

- Days of our Goddess

- Advertence

- Cranberry Thyme

- Grooves

- Some Facts About Dawn

- Simulcast

- Miniature Donuts

- The Cardinal

- Tiny God

- The Last Wrong Turn

- Every Solid Thing Casts a Shadow

- No Life Forms Detected

- Fishy Pants

- Dead Mother Card

- I Want That Tomorrow

- The Pitch Perfect

- Pure Trash

- L’Emergency Bars

- With These Wings I Set Thee Free

- Ah Ma is a Reusable Bag

Recent Comments