by Joseph Hernandez | Jun 24, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

On the morning of her last day alive, Tía Reina awoke with a halo of bright pink aligning her forehead.

“A fever,” she told us. “It will pass.”

What she didn’t know then was that she had become a saint overnight (this we learned posthumously, after consulting a couple of priests, a friend of a relative’s Sunday school teacher, and after almost getting in touch with the Vatican). There had been a hitch, we deduced, in the saintmarking process, and Reina had been appointed before her passing when normally this happened after death, in the bodyless limbo of Judgment.

To ease the pain, we offered her Aspirin and ice, but she wouldn’t take anything. She even declined any homemade remedies that would usually do the trick.

“It will go away,” she said. “I feel fine.” Then she went to the closet, pulled out a bucket and a mop, and started to clean around the whole house.

Towards the end of her life, Reina had had three main priorities: her faith, her home, and her family. Despite constant pressure from her mother, she never married or had any children of her own. Her life had become a perpetual cycle of cooking, cleaning, and praying.

“I am happy with what I do,” she’d explain, amid our badgering at family get-togethers. “I am at peace when I can think and breathe in a clean, white room.”

The church she attended was all white, too, both inside and outside, with the exception of the wooden pews and the kaleidoscope of colors from the stained-glass windows. We’d even joked that her house was more spotless than the holy house, much to her objection.

By late morning, a soft glow had adorned her long, brown hair, so that it looked reddish in the light. She had always been marveled at for her fairer complexion, while many of us had darker features, so this new luminosity rendered her all the more outstanding.

When covering her head in a scarf did nothing to subdue her hairlight, she clicked on all the house lamps despite the early hour.

“My old eyes need to see better,” she said as she filled a large plastic bowl with water from the kitchen sink.

After this, she began her alchemy of disinfection, hunched over the bowl as if it were a neon-colored cauldron. This was a science only she knew – how many droplets of green soap; whether to add baking soda or bleach, vinegar or lemon juice. She would stir the contents, humming quietly to herself, until the whole of the kitchen smelled sterile (we sometimes wondered if the fumes alone could erase grime). Next, she would soak rags of old t-shirts in the mixture and use these to wipe countertops, windowsills, and tables alike. A bowlful of this concoction usually lasted half a week, by which point the surfaces of Reina’s home were immaculate enough to turn tap water holy.

When Tía Reina’s ritual of cleaning was finally finished for the day, she sat to eat dinner. Though she normally cooked for all of us, even after all her labor, today she moved more slowly.

“Don’t strain yourself,” we told her. “Let us cook for you.”

We supped at a small table, plastic and round. One of the legs was shorter than the others so that the table wobbled every time someone moved a plate of carne or a bowl of frijoles. Later, we’d remember this as Reina’s last time enjoying carne, frijoles, and tortillas. She ate everything with great fervor, and when she was finished, she didn’t belch as she normally did. Instead, she bowed her head and said another round of grace.

After dinner, she went to her bedroom to rest. As she stood to leave the table, she swayed, gripping the rungs of a wooden chair for support. When she found it difficult to take a step, she called for one of us to help her. By now, her entire body had been dressed in brightness, setting the kitchen aglow as if touched by sunlight.

“The fever,” she said. “Too hot.” Her eyes were closed as she said this. We guided her to her room and laid her on her bed as gently as a sacrament, then kissed her searing forehead and left her for the night.

We found her the next morning, well past the mopping hour. On any other day of her life, her floors would be glistening with wet by now, her hands smelling strongly of detergent and lemons. She lay on her bed, unmoving. All light had left her now. We bent low over her, touched her upon the brow, and said some prayers.

In time, the Heads of Church came and marked the house as a Holy Sight, the Church’s devout equivalent of a crime scene. Where cautionary tape would be stretched across the outside fences; instead, a perimeter of holy water was sprinkled around the yard.

And though Tía Reina was gone, her kitchen retained its immaculacy. The room was so white it glowed, and what was believed to be a divine layer of bleach and supermarket-grade cleaning products prevented any filth from ever appearing on the walls and floors. Eventually, it was converted into a shrine to commemorate the Patron Lady of Soap and Water and was named ‘The Church of Our Lady of Clean Kitchens.’ Mothers and grandmothers from different counties would bring their children and surround the sanctuary with biblical simulacra wrapped neatly in saran; babies were brought to be baptized in the sink; the oven was used to make sacramental bread. We held services once a week, only on Sundays, to propagate the teachings of Santa Reina. Throughout, our hymns and voices echoed like the sound of running water spilling from a faucet.

by Kathryn Aldridge-Morris | Jun 19, 2024 | micro

At some point, we’ll forget the rabbit’s name, how it came to die, the rush we were in to bury it, and when people ask, we’ll shrug, and Vince will snarl his upper lip in the way his body’s patterned to do since we went into care. But right now, we tip marbles and red and yellow plastic straws onto the kitchen floor of this latest house and lump Nibbles’ body, still warm from the tumble dryer, into the Ker Plunk box. I fetch straw from his hutch and pack him in, nice and cosy. It’s Vince’s idea to bury him under the willow in the back garden, so we take an edge each and carry the Hasbro coffin into the chill autumn air. Vince digs a shallow grave with his scarred hands, and I lay the box in the earth. I give a short speech — you were a good rabbit, you never bit etc etc — and Vince pulls a carrot from his back pocket and drops it in. Maybe it was that. The carrot. Maybe that was the moment when we just kinda knew we were good at this. Burying bodies. And killing things. Or maybe it was when we heard our foster mother scream, and we ran back into the kitchen to find her lying on her back, legs akimbo like Woody in Toy Story, her head bleeding out over the marbles. In years to come, they’ll say we didn’t kill her. They’ll say you poor things, write about childhoods lost. They’ll even say we didn’t kill the rabbit. But right now, we know we’ve got to get rid of another body, the branches of the willow whisper us back and we’ve never felt so vital, so alive.

Originally published in Reflex Fiction.

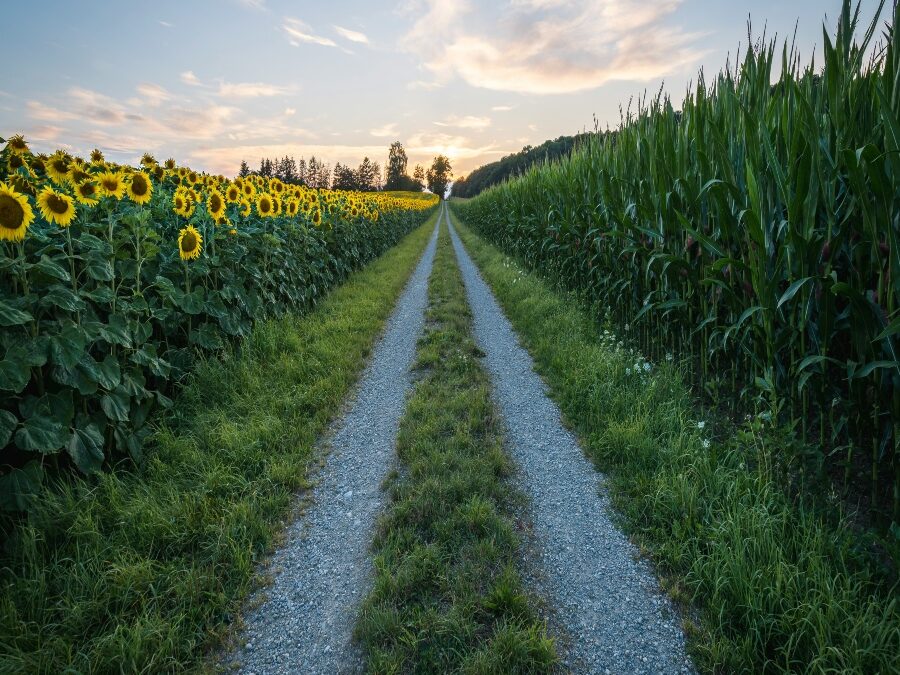

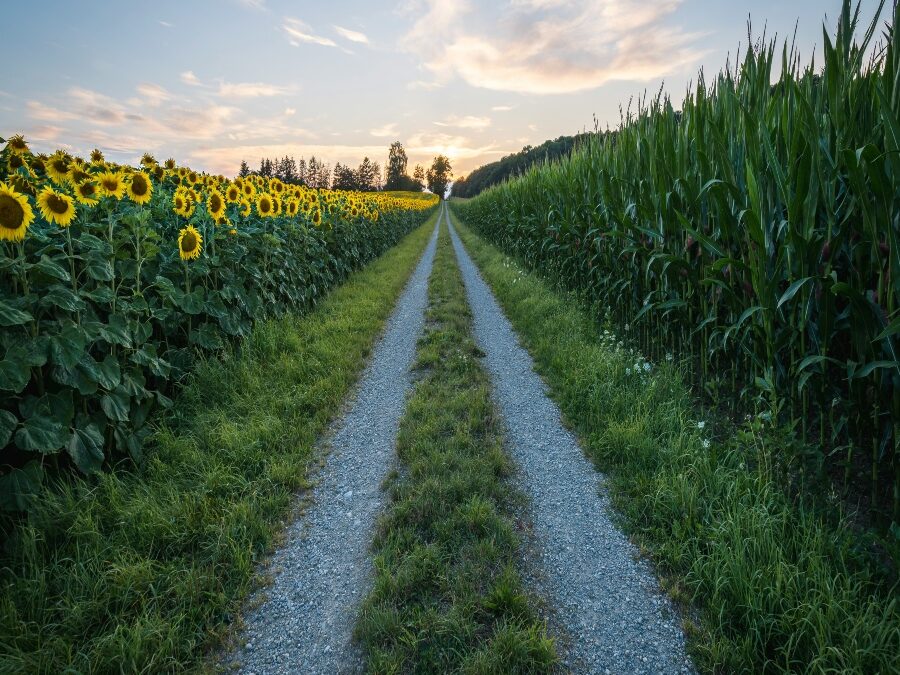

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

by Fractured Lit | Jun 17, 2024 | news

The winner is The Breakfast Shift at the Usual New York Diner by Debra A. Daniel!

Thank you, and congratulations to our shortlisted writers. We so enjoyed reading your stories about work/play for this challenge!

- HR by Chris Bruce

- The Librarian Dana Jaye Cadman

- Dresden, Germany–October 1995 by Kay Rae Chomic

- The Breakfast Shift at the Usual New York Diner by Debra A. Daniel

- This is Not a Drill by Kathleen Furin

- The Cat Knows Your Lies by Richard Hughes

- Pellucidity by Alison Mills

- Cop’s Boy by Jerome Newsome

- Clickety-Clack by Samantha Silva

- Rowan, Rowan by Laura Theis

- So Much Here is Green by Juan Fernando Villagómez

- Missionaries by Rebecca Winterer

by Jeffrey Hermann | Jun 17, 2024 | micro

There’s a beautiful beach. You get there by walking through a shady path, and then you’re on the soft sand. Some low hills far off, green and silver in the sun. There’s a couple on the beach. The woman on a towel with a hat to shade her eyes. The man in the water up to his calves, sifting through stones he pulls up from the bottom. He finds the one he wants and brings it to the woman. This stone, he says, spent a million years in the dark, part of some bigger layer of earth. Then, it spent a million in the light, sunning itself on the hillside. Then, a million underwater. Now it’s in my palm and I’m handing it to you and now it stands for love. It means I love you. She takes the stone. It’s a blue agate, smooth, with a ribbon of bronze. She holds it, and they kiss. Then, quick as a flash, another million years pass. Everyone in the story is gone. I’m gone. You’re gone. But the stone remains the stone. It is still smooth and blue with a ribbon of bronze, and it still stands for love. I’m telling you, it still means I love you.

by Melissa Llanes Brownlee | Jun 13, 2024 | micro

I once fucked a guy in a redwood water tank. The kind that once held water caught from rain, maybe filled by the county every couple of months. The kind that now looks like a dorm room, a single bed pushed against rounded walls, a small fridge next to a tiny table and chair, the toilet, in a separate little building, the shower, outdoors, in a tiled oasis of monstera and palms.

After I fucked the guy in the redwood water tank, his spent body sprawled across his tiny bed with no room for me, I took a shower under the stars, using what hot water he had in his heater, cleaning the lukewarm sex, the alcohol sweat, the questionable choices from my skin, the night air caressing me, more a lover than whoever it was I had just spent the last couple of hours with.

The guy I had just fucked in the redwood water tank didn’t wake up as I searched his fridge for something to drink, the water beading off my naked body onto his redwood floor. A cold beer in my hand, I sat at his tiny table, my legs akimbo, running the can across my skin, still warm from the shower, before opening it, and I waited for him to wake up and take me home, long cold pulls slaking my parched throat.

by Fractured Lit | Jun 10, 2024 | news

We’re so excited to announce our Anthology 4 winners! Judge Morgan Talty chose 20 stories to be published both online and in print! Thank you to everyone who submitted and to our finalists. It’s never easy choosing only twenty stories from all of the great ones we received for this year’s contest!

- Protocol for What to Do After Hearing Another Rape Story in Exam Room Five by Margaret Adams

- Departures by Sandra Arnold

- The Eulogy Competition by Lisa Ferranti

- Could Die for Just a Lie Down by Elissa Field

- Act As If by Miriam Gershow

- Newfoundland by Phillip Grady

- True Story by L Mari Harris

- The Last Laugh by M. Lea Gray

- This Time of Death by Wendy Holmes

- Diorama of Star-Crossed Lovers Driving at Night by James Humes

- Those Who Seek by Lori Isbell

- Safe Passage by Elia Karra

- Hug Me by Mimi Manyin

- Thirteen by Betty Martin

- The Children by Sara McKinney

- When The Giant Breathed by Zach Moser

- SELF-PRESERVATION Danielle Mund

- Flesh Wounds by Tanya Nikiforova

- The Life of the Mother by Susan Perabo

- We Went to the Museum by Chris Negron

by Dustin M. Hoffman | Jun 10, 2024 | flash fiction

The astronaut pushes a wire cart through the supermarket. Their body is obscured beneath the thick, radiation-proof fabric. Their face hides behind the mirrored shield opaque enough to block the sun. We decide to assume the astronaut is a she, for women make better astronauts.

The astronaut is squeezing avocados. She is counting bananas. She is weighing envy apples on a chromium scale. She holds a zucchini up to her reflective visor, as if sniffing. The mirrored surface doubles the zucchini. We encounter her again near the deli, and we nod and smile, but she’s busy trying to gain the butcher’s attention. Two salmon filets, she signals to the butcher by tapping a pointer finger on the glass at the ruby flesh and then making a V shape with her fingers.

So she’s shopping for a partner. Space is lonely without a lover. We are pleased for her to have company.

Her cart blocks our path in the cereal aisle, where the astronaut is selecting a box of bran flakes—practical and efficient. We wait patiently, try not to ogle. She pulls a box of Lucky Charms, turns the box to read the side, and despite so many inscrutable ingredients she places the box in her cart. Should we warn her about the article we read identifying potentially carcinogenic dyes? We do not, for we need a box of Lucky Charms to take home to our own children. It’s all they’ll eat most mornings. We’ll take potential doom over starvation. We’ll risk spoiling over withering.

And what of the astronaut’s progeny? We must follow her into the next aisle, where she buzzes past the diapers. Her own undergarments, we know, must be the same as all astronauts wear, briefs regulated by NASA, designed to capture all biological waste. We know this, but not what purchase comes next. No diaper cream for her. No formula. No baby shampoo. So why even bother here? But, then she reaches the deodorant, and we pretend to busy ourselves examining diaper boxes, though our children are teenagers now. We’re not fooling anyone into mistaking us for new parents with our plentiful gray hairs. The astronaut seems enraptured by the deodorant choices, each plastic container shaped like a rocket, helmeted with a transparent shell. A dizzying row of mini astronauts awaits her selection. She lifts them to her visor, taps them against her glass. Old Spice, Secret, Degree, Teen Spirit. She might spend all day deciding, we think, before she tosses a stain-reducing Arm and Hammer into her cart.

We imagine an astronaut’s body as a work of art, a stringent discipline of muscled perfection and grace. There should be no business in the junk food aisle. Yet the astronaut fills the cart with Doritos, one bag of each flavor, including the new pickle one that no one could possibly enjoy. Oreo cookies with triple stuff pass through her gloved fingers. She’s going for all the name-brand products, no knock-offs, and we’re pleased our American space heroes are compensated handsomely. Then we remember NASA is funded by our tax dollars, as we select a small box of store-brand oatmeal cookies. Resentment bristles within us, and we unaccidentally bump her cart as we pass.

She bows her head in apology. Draws fingers to her visor, where her lips would be.

We feel our face burning red with shame and wish for our own helmets and opaque visors that we pay for but shall never own.

Onward, we go to our separate shopping paths.

But, of course, we meet again in the next aisle. It can’t really be avoided. We’re all victims to the supermarket design, its maze of human traffic like arteries, and we are helpless blood cells rushing through the current of life, ships passing in the night. One awkward encounter leads to another and another. We loyal consumers begin the cycle again, from produce to frozen, again and again, amen.

We wave as we pass the astronaut beside the frozen dinners. She waves back. We wonder how many millions of tax dollars just one astronaut glove costs. We inquire into the tiny screens of our smartphones. One hundred million dollars, on average, per suit in the 1970s. Today’s suits edge toward one billion. We choke on our chewing gum. We briefly consider a minor assault in the parking lot, nabbing just one piece of the suit. We’d pay off our mortgage with one garment. But what good is a suit missing even just the left glove’s pinky finger? The hermetic seal kept against space is as essential as our beef flank’s cellophane.

Instead of assault and theft, we observe the astronaut loading single frozen dinners into her cart by the armful. One of each. One of every single dinner from the ultra-organic vegan selections all the way down to the slums of the Banquet Salisbury steak. She will try them all, each one. These meals seem proof against partner—the frozen dinner standing as the quintessential purchase of solitude. Our envy slides away, like sloughing off the heaviest suit of lead-lined Kevlar. Space is lonely darkness. A single hydrogen atom floats per cubic meter in deep space. There exist countless galaxies of emptiness to traverse, enough time to sample every meal that’s ever been frozen, every Doritos flavor that has and will ever be invented.

We have no need for frozen meals. We work from home. We cook for our partner some nights, and other nights they cook for us. Our feet never leave the floor, always married to gravity, rooted in its grip.

If our nosiness couldn’t be misinterpreted, we’d gift the astronaut all our coupons. We’d wish them well. We’d take great pleasure when the cashier flirts, joking about freezer space as massive as the ISS. Both astronaut and cashier might chuckle, both locking eyes through the visor, a blush blooming for one to see and one to hope.

by Patricia Q. Bidar | Jun 6, 2024 | flash fiction

1.

The fourth-grade mothers learn that one of the fourth-grade girls, Jade, is missing. Their sons and daughters announce this at the dinner tables. The children are reluctant to provide the news. Nothing like this has happened before, and they don’t know how the mothers—who the children are old enough to be mortified by—will react.

The fourth-grade mothers are all in. It is summer and there is plenty of light. They will take the school playground and its adjoining toddler yard. They will take the library parking lot. The area around the Veteran’s Building; the middle school track. Filled with mission and flanked by their jacketed children. Their fourth-grade children call out too softly for anyone but the mothers to hear them. Their babies babble and point.

None of them know this child, this family. Her parents are lithe and smiling runners who show up in their office clothes to every PTA meeting. One or the other of them always offers themselves for any new committee. The best of them, even though they can’t think of this couple as “of them,” at least not yet.

2.

At the PTA meetings, the wifely eyes slide over to this husband, whose Facebook handle is SurferDan. They sometimes pore over his page when their husbands are asleep but none of them braves a friend request. On PTA nights, the fathers pack the kids into their trucks for the pizza parlor with the cartoons and the cheap pitchers. Their husbands at the annual motel pool wear bucket hats and dark t shirts.

The mothers see this husband and wife in the early mornings, running like deer in the dim streets before work. No, none of them know this elegant family with its single child and desertscaped yard. Their kids are not even friends with this now glamorous, glittering girl.

Because their kids are all connected by their smartphones, the fourth-grade mothers learn that Jade had a fight with her mother! Wears thong underpants! Ran out in the night, in her sweats and socks!

Now, the mothers’ smartphones start to buzz. The missing girl is so grown, they text. One of the very few fourth-grade girls to need a bra. Sneaks out at night. Got her period early. Suddenly, the mothers need to get back to cooled sinks of sudsy dishes. To baths and the choosing of outfits for the next day. They haven’t weaned the last of the babies yet, haven’t fully returned to their bodies.

It’s bedtime. A few minutes of reading. One or two of the mothers stretch tentative fingertips to their husband’s chests, shoulders, hips. In their sleep, their torn-off acrylic nails become lost in the sheets.

3.

Morning. Their husbands have left for their cubicles and jobsites, so the houses, the kids, belong to the moms. Who run to hug their flat-chested daughters and compliant sons. The fourth graders have already forgotten last night’s search. So the mothers have to ask them how far the girl got and the children say Jade is home; she’s fine. The mothers hedge their advantage by pushing extra granola bars and Rice Krispie Treats into brown sacks. They’re for Jade, give them to Jade.

Who has terrorized the fourth-grade mothers. They don’t know what to do with their husbands, their children, the other PTA mothers, whom they realize now they hate. They haven’t been visited by chaos. But now they know it is only a matter of time, that chaos will extend its slim fingers for them all.

by Fractured Lit | Jun 6, 2024 | news

We have narrowed down the total submissions for this challenge to 12 stories for the shortlist. We’re making final decisions now and will announce the winner early next week! It’s always so fun to see how writers interpret these challenge prompts.

- HR

- The Librarian

- Dresden, Germany–October 1995

- The Breakfast Shift at the Usual New York Diner

- This is Not a Drill

- The Cat Knows Your Lies

- Pellucidity

- Cop’s Boy

- Clickety-Clack

- Rowan, Rowan

- So Much Here is Green

- Missionaries

by Fractured Lit | Jun 5, 2024 | news

We’re so thankful to partner with Judge Aimee Bender on this prize. She was so impressed with the shortlisted stories that she chose co-second-place winners, so we will honor four stories with prize money and publication!

1st Place: To the Tower by Skyler Melnick

2nd Place: The Desert Sound by Mikhaela Woodward

2nd Place: The Pebble and the Witch by Emma Li

3rd Place: Our Lady of Clean Kitchens by Joseph Hernandez

- Dear Goldilocks by Amy Marques

- Heart of Stone by Sylvie Althoff

- The Incantation by m.a. biddle

- The Nesting Doll Paradigm by Nadia Born

- The Boy Who Couldn’t Sleep by Sam Boyer

- Heterothermy by Hannah Brown

- He is the River Monster by Chris Corlew

- The Cycle by Lucienne Cummings

- Her Little Animal by Anissa Elmerraji

- Narrative Seeds by Jane Garrett

- Cordelia’s Ghosts by Cynde Gregory

- Our Lady of Clean Kitchens by Joseph Hernandez

- Black with Ash, Red with Grinding by Chip Houser

- Second Sight by Gaynor Jones

- To Pay the Piper by Julian Koslow

- The Last Time I Saw Frank by Aimee LaBrie

- A Fairy Tale for Florida Girls by Janice Leadingham

- The Pebble and the Witch by Emma Li

- To the Tower by Skyler Melnick

- Animal Nature by Kim Steutermann Rogers

- Thank You For Coming by Sarah Elizabeth Schantz

- Mama Bear by Dr. Michelle Tousignant

- At Whistling by Cameron Walker

- The Desert Sound by Mikhaela Woodward

- Let Down by Calla Wright

Recent Comments