by Phillip Grady | Jul 29, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

We put our seed in the ground and buried a body, but the land gave us nothing in return for the price we paid for it, for the weight of the earth that we piled onto someone who was our own. And after such a loss, what else did we expect? We wandered through our own house. Front door impossible, backyard a stranger. Attempted to communicate with others in a language we no longer spoke. The ache inside us was no surprise, especially when it bled out into our everyday lives, venting through cracks and fractures. We pretended we had nothing left to lose, although we were wrong about that, of course. I lost you in the wet heat outside Atlanta, stuck in traffic, while you fussed with the air conditioner. We were both scorched and empty, like a kettle screaming on a burner as the water boils off into steam. You were sorry, and I was sorry, and I said goodbye so I didn’t have to feel sorry all the time.

I rode trains north, carried along as if on a fast river. Seven hundred miles with a paperback thriller someone had forgotten, interrupted only by the announcements of miscellaneous towns. I abandoned the train in Washington, and I hurried down the National Mall, ignoring monuments dedicated to wars and wars and murder. Things were better in Baltimore, with pit beef on a kaiser and greasy fingers, a calm looseness blooming in my head. The nights were becoming easier. I was sleeping past dawn again. In Philadelphia, I looked five years younger, and although I wasn’t the person I used to be, I pretended to be that person, if only for a minute.

I was content with life in motion, suspended halfway between leaving and arriving. In Manhattan, I waded through trapped heat to Penn Station. I was excited by the idea of Providence, something that was absent from me and that I longed for. At Providence Station, I asked about beaches and how to get there, and I swam in chest-high surf. Rolling waves, one after another, the water full of stringy, rust-colored seaweed that reminded me of swimming in hair. The forest in Maine was silent in October, the floor cushioned with spent pine needles. A woman warned me about bears, and when to run, and when to puff up and yell. Sprays of steam from a teakettle on a cabin stove in thin, cold air. A reoccurring dream of Atlanta shook me from my stupor. I missed you constantly. How far away could I get from you? Where was the opposite of you? The road was the arrow of a compass pointing north.

Whenever people asked questions, I’d gesture behind me and make something up. Any other past was preferable to my own. I had a degree in history, so I was a professional. I could invent any past that I wanted. Where was I from? What work did I do? Phoenician trader, Mesopotamian brewer, goat herding on the steppe. But not from here. From anywhere, everywhere else.

I started walking. Sometimes, I dropped off the road and slept in a ditch—days of sore feet and police with questions. I bought boots and winter clothes in Augusta. Miles of blisters. Frost on gravel shoulders. Loaves of sandwich bread smeared with peanut butter. Instant noodles cooked with hot tap water. The life of economy, with each step creating a debt inside myself that I had no means of repaying. I was spending the part of me that I couldn’t hope to earn back. Poorer after every next minute, but always another mile, and a mile after that.

There was a sickness that got in me as I continued north. I began to slow down. Christmas Eve in a coffee shop, eavesdropping on two elderly men. Years spent together, their families raised as neighbors, each of them planted in the soil of their community eighty years earlier. As they talked, I was missing my own roots, which were gone. Then the old shits made racist comments about our server after she refilled the coffee cups. I fortified my coffee with cream and sugar for the extra calories, savored the hot nectar, and I was jealous. They had somewhere to go. People waiting for them.

Put a body in the ground, walk to Canada and find myself still on the same earth, as if on a treadmill, no further than where I started from.

I dreamed of you in a park with our girl, and a wind that thrashed the branches overhead and whipped your hair around. Maybe it would rain, or maybe not. “Should we go?” That’s what you asked me.

I couldn’t see our girl because you were in the way.

I was in a motel room in the middle of nowhere, flossing my teeth. I had a look in the mirror, and I thought: Goddamn, aren’t you a mess? You look terrible.

But I was flossing my teeth. I was trying. The awful parts of me were trying to become better again.

Along the coast of Nova Scotia, waves pounded the beach and raked tumbling, small stones out on the recede. I was sitting cross-legged, hands tucked in my pockets, my head churning and busy. My heart no longer hard, but heavy, living in the pit of my stomach. New Brunswick to Quebec, over the St. Lawrence and north to Newfoundland. I liked the sound of Newfoundland.

In the dead weeks before real spring, I was raw and hungry. Lips and fingertips chapped and cracked. My boots sank in mud and I worried about my feet, trying to look after them with pairs of hand-washed socks while I begged the sun overhead for warmth.

Cold mornings. Foggy, shrouding, unwelcome icy rains.

All the way to the horizon if we can, if we let ourselves, if we’re doing it right, and then we turn around.

by Miriam Gershow | Jul 25, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

In the bottom of Zadie’s purse, as she sits in a lightly upholstered chair at the DMV to get her license reinstated, everyone packed in side by side by side, Zadie number 23 with number 72 currently being served:

- A half-wrapped mint filched from the bowl on the hostess stand at the Mexican restaurant Phil drove them to last Wednesday, the mints there for the taking, but Zadie with the feeling she was stealing, Zadie always with the feeling of being caught, the unwrapped half tacky to the touch, gathering lint;

- Lint from wadded up tissues for nagging allergies and occasional (if no longer frequent) crying jags;

- One useless tampon still in its crinkly wrapper, hearkening a bygone era, testament to Zadie’s wont toward accumulation, everything gathering and taking permanent root;

- Nicorette gum 15-pack, four pieces left, 11 hollows in the plastic packaging big enough for the tip of her ring finger to fit in and out of, like playing hidden harmonica, good for keeping her hands busy;

- Red chip that replaced first Zadie’s beginner’s-luck green chip, then later, her claw-her-way-back, mouth-full-of-hot-spit-day-after-day silver chip;

- Auto insurance card with a quarterly premium that could buy instead a halfway decent used couch off Craigslist, three credits at the nearest community college for training in auto maintenance or graphic design, ten bottles of single barrel straight bourbon;

- The flip phone she’d replaced her smartphone with, so she’d have one less thing calling out every second of every day for wanting;

- The signed Certificate of Completion from Tonya, the hippy (as in pear-shaped, not as in pot-smoking) teacher who lectured about response times and legal definition of impaired and classifications of drugs to a roomful of students that should have made Zadie feel camaraderie, though mostly she was distracted by the yellow-haired girl who picked each week at the badly healing tattoo of everyone’s favorite cartoon rabbit on her inner arm;

- Empty pack of Marlboro Reds, the insides still smelling of free fall and possibility in a way that was supposed to repel Zadie but did not;

- Bent-to-hell photo of her father (dead) holding Zadie and Phil’s infant son (grown and gone) gazing at each other in a manner which neither gazed at her so far as she could remember;

- Dumb piece of paper with dumb three-word aphorism written on it that she’d referred to a startling number of times during the days and hours of her mouth full of hot spit and now just had to rub between her thumb and finger to remember its dumbness, its dumbness sometimes helping, so dumb;

- Key ring with her house key and her car key that she’d kept on this whole time, a carrot or a stick, she was not sure; a taunt of encouragement: Come on, you asshole;

- Empty Altoids tin, cool in her fist till she warmed it, a feeling of power in warming it. There she was. She was there. Here. Here she was;

- The number 23 tab she’d pulled from the dispenser after the Uber dropped her in front of the DMV, her thinking without thinking, My lucky number, even if Zadie had never been one to believe in such a thing—too whimsical—though 23 would be from here on out, lucky, even if she did not recognize it as such, a nameless warmth when she spotted 23 on a mile marker or in the license plate ahead of her on the back of a pickup, she misunderstanding luck as random anointment, not of her sweat, her effort, her own hourly, daily making and remaking.

by Elissa Field | Jul 22, 2024 | flash fiction

Beatriz had been insisting since waking that we go to the house at the top of our road, on the rise above the sea. I was barely moving—even a four-year-old should sense something amiss when the full weight of her tugging on each of my limbs has not moved the hull of me off the beached headland of the couch.

The week before Beatriz was born, a whale beached herself down on the strand, all of us from the estate barnacled, staring beneath the dune, hands covering our mouths each time the great maw gasped its epic exhale in exhaustion.

In my mind, I’m telling Beatriz this story. It is half fairy tale: titian glow of dawn gilding the silky sands of that long stretch of beach in the cup of our bay, all magic and hope. It is half cautionary tale, all the fangs and evil trees and ragged wolf pelts and failed miracles of Grimm.

Our neighbor at the top of the road, Lorna, has hung pictures of angry cats in every window of her house to discourage a chaffinch that had been concussing itself in an effort to kill his own reflection in the glass. Beatriz has seen the cats and is sure they are a sign: she had asked for a kitten. We had a cat, but he’d wandered off. Left me alone with this feral energy balled up and demanding: Beatriz tugs me by the fingers, by my elbows, my feet. “Lorna hung them for meeee… We need to goooooooo, go noowwwwww…”

In my head, I am telling her the exact slate blue of the whale, exact slow rotation of her eye. Gorgeous death, sighing sea air—sky pink—there where our children picked shells and bits of slate, piled turrets and moats. Scientists up from the aquarium told us the whale was healthy. Not yet middle-aged. A mother. A ring of boats had garlanded the bay like some tourist postcard, doing their best to herd the whale’s confused calf, not yet sure how to surface and breathe. Let alone feed. “Selfish bitch!” Lorna had hissed at my elbow. Out of habit, I’d muttered, “Sorry,” without the superstition, yet, to worry that I’d hexed myself. Taken on that sorry and longing and broken navigation and overloaded sonar and misplaced mothering skills. I felt Beatriz somersault in the ever-tighter confines that pushed my entrails into crevices beneath my ribs, felt that giddy tickle of her hiccup, that scrape of glitter and hope. “She is still breathing,” the scientist said of the whale, and Lorna had laughed at me, said I was crying when I answered, “Of course she is.”

Finally, I give in—ask Beatriz, “What is it, love?” Not realizing I’m responding not to her question but her absence. My Beatriz. Her badger-dark eyes. The hedgehog-spite of her hair. Her rabbity stillness and sudden movement. The shrillness of her joy.

She has gone out, gone alone up the street to the house on the corner.

I can’t breathe, of a sudden.

The weight, it must have been. Can you imagine? All your life, the utter weight of you buoyed by the crush of ocean around you. And that one time, that one time, just the once, you think, It would be so nice to lie down. To not swim. Not surface to breathe, not breach, not trap clouds of sardine in a blast of spiraled bubbles. Not nudge the baby, over and over, to the surface. Just. Just lie down a bit. That silken beach over yon. The way it warms with the sun. Just a lie-down, just a minute. Just a rest.

Beatriz comes back down the road to me. All those fears, but truth is, our calves don’t stray, not even when they should. The bounce of light in her auburn crazed halo, the ludicrous rise of her arms like antennae, reaching for the glitter ball above a dance floor, useless for streamlining her run, useless for maintaining balance, all Woo Woo and celebration. Raises a picture in each hand, her miniature parade banners. My neighbor—god fuck me, if it isn’t Lorna—tight-wrapping her cardigan ’round herself, smug and judgmental in Bea’s wake.

“My told you, my told you!” Beatriz singsong chastises, balloon-burst of noise come back in through the door.

I’m on my “good company” behavior now—I’ve sat up, pushed a hand through my hair. Beatriz is in my lap in an instant, the pictures smashed against my eyes so I could see what I was too stubborn to take her to get. Lorna will move more slowly. So much judging to itemize, moving from the open back door through the kitchen. Stacked sink, open boxes, cups upon cups, heaped laundry, dropped shoes.

“It is a cat,” I tell Bea, “I see that.”

“Noooo,” she corrects me, because again I am wrong. Pushes both pictures against my cheeks, presses hard. I might get it then. “Two cats!”

“You are so clever!” I praise her, because we are supposed to affirm our daughters, feed them positive images for themselves from a young age so they can see the full wide range of chances available in their future. My eyes are tracking Lorna. Sounds come from her that are not words. She is my mother tsk-ing. She is my grans.

“Ninety-one tons,” I say, and my beautiful Bea asks, “Is that a lot? Is that how many cats?”

Ninety-one tons, that whale would have weighed once she’d eased herself out of water and onto land. The crush of it. Just for the sake of a lie-down. And all of them, out there in the bay, bobbing in their bright colored boats, heads turned to murmur, “Selfish bitch!” for what she’d done. For what she’d done to that little pale calf out there, cavorting in the waves.

by Lisa Ferranti | Jul 18, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

My father tells all three of us to write a eulogy and he’ll decide who gets to deliver theirs at our mother’s funeral in five days. Tom’s jaw sets, determined. Diane nods, eager to please. I narrow my eyes at Dad, resenting the competition he fuels between us, even as adults. I’m the youngest, nicknamed Flaky Suzy, and I will not win. The sweaty-palmed funeral director ushers us to the door. The flowers in the hallway are plastic but I swear I can smell gardenias, Mom’s favorite.

We have our marching orders and go our separate ways. Being the least responsible, I’ve been assigned relatively few duties, so I head to the coffee shop with my notebook and consider what to say about Mom.

Should I tell about the time she won top prize for flower arranging at the state fair? How I’d never seen her smile so wide, not even when Tommy was state swimming champ.

Or about when she was PTA president and planned the best school carnival ever, with a dunking booth. For one dollar we could try to dunk the principal and teachers. But that’s more Tom’s story, since he holds the record from that day.

The story about finding our dog, Lucille, is a good one. Dad was at work and the four of us searched for hours. Tom and Diane pedaled off on their bikes, and I rode in the car with Mom. She drove slowly and I hollered Lucy out the window. Diane is the hero of that tale, though, finding Lucy trapped inside our neighbor’s pool fence and bringing her home just as we pulled into the driveway.

Should I tell about the times Mom let me play hooky from high school? How she would call the office to say I had a cold and would be absent, my face growing hot, not with fever but with excitement that I’d get to spend the day alone with her. How we’d play gin rummy for hours. She smoked while we played, catching ashes in an old coffee can, sometimes letting me smoke too. At the end of the day, we opened windows, sprayed air freshener. Before I’d go to change out of my fake sick-day pajamas, she’d hand me the coffee can, lid on, to hide in my bedroom closet, a place Dad would never venture.

Should I tell about the time she confided to me she wanted a tattoo but couldn’t decide what to get? I’d sketched a rose as a suggestion. “Maybe my initials instead,” she said, and I penned a scripty MS. She smirked, saying we’d have to add her middle initial or it would look like it stood for multiple sclerosis. She never got a tattoo, but I wonder if we breathed life into the idea? If that was the day her body birthed the germ of the disease, marking her on the inside because ink never did bloom on her skin?

Or what about when she showed up at my apartment, braving the sketchy part of town where I lived in an artist loft with five friends, including boys. How we sat on the threadbare sofa, and I jokingly offered her a shot of whiskey. The bottle was on the coffee table from the night before, when we’d toasted my first modest commission from selling a painting. She accepted the shot, and a cold chill ran through me. She came to me because she knew I could help her—that I was maybe the only person who could. I held her hand when she said, “Suzy, can you imagine, at my age?” I didn’t judge when she said, “With you kids grown, I finally have a life again. No offense.” Her finger circled the rim of her glass.

We planned it for when my dad was away on business. I drove her to the clinic and stayed with her for two days at home, the first day telling Dad she was napping when he called.

I didn’t know then how often I would tell my dad half-truths. How it would continue long after Mom’s death.

Three days before her funeral, in an uncharacteristic act of democracy, Dad tells the three of us to decide who will deliver the eulogy. We determine all of us will speak. It’s only fair.

At the service, I listen to my brother and sister. To Tom’s precise words, no less meaningful for their razor-sharp exactness. I smile at Diane gushing about Mom being a wonderful grandmother, how happy she is that she (she doesn’t say she alone, but I hear it) was able to give Mom that gift.

I go last, of course, and I tone down my words, leaving only a little of the color everyone expects from me.

I don’t tell that when Lucille was lost all those years ago, Mom and I sat for a long time in the drugstore parking lot, not searching. How she said maybe we should just let the damn dog stay lost, then maybe Dad, who took Lucy hunting on weekends, would pay more attention to her again.

I can tell my family holds their breath, just a little, until I finish. And I enjoy, just a little, my power over them.

I will not tell them that there should be a fourth of us to speak. A boy or girl who would now be twenty-two years old. A younger sibling that never was. I wonder what our brother or sister would say if they could. Would they be angry about Mom’s decision, the one she questioned at times but was still glad she got to choose? Would they add to the unspoken chorus of who loved Mom more? Who loved her best? I know we all loved her best, each in our own way. But I also know there’s no competition, really, because I’m the one who knew her best.

by Sandra Arnold | Jul 17, 2024 | contest winner, micro

A plane ploughs through the clouds as she scrubs and cleans the plugholes in the washbasins and the kitchen sink and the laundry and another plane ploughs when she mops the floors and washes the benches and polishes the windows and another plane ploughs when she reorders all the cupboards and drawers until finally everything is done and she can go into her garden where the only sounds she hears are birds singing in the trees that her daughter used to climb and she cuts camelias from the bush her daughter used to love because the blooms were pink and then she goes back into the house to sit in the glint and the gleam and breathe in the scent of flowers as she recalls her father’s fury in the days before Facebook and Zoom and email when she told him she was leaving for the other side of the world and he roared that her mother had never stopped crying since and insisted she wait until they were dead before she left but she didn’t wait and she said it was her right to choose her own life so this morning at the airport before her daughter departed she told her to be happy and they both knew there was Facebook and Zoom and email and after she waved goodbye she headed home and scrubbed and cleaned and polished for the rest of the day with the roar of planes inside her head and now the sun sinks and the sky glows pink and she drops into a chair in the pink-tinged dusk with her eyes closed and a pink camelia held to her cheek.

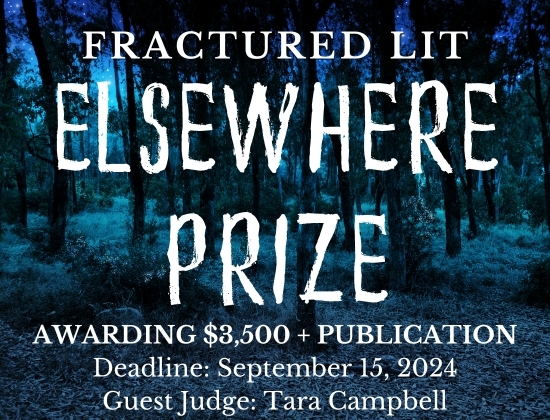

by Fractured Lit | Jul 16, 2024 | contests

judged by Tara Campbell

July 21 to September 15, 2024 (Closed)

Add to Calendar

submit

This contest is now closed. Thank you to everyone who entered! We can’t wait to read your stories!

We’re excited to bring back another favorite contest! From July 21 to September 15, 2024, we welcome submissions to the Fractured Lit Elsewhere Prize.

“In a world of diminishing mystery, the unknown persists.”

― Jhumpa Lahiri, The Lowland

For this contest, we want writers to show us the forgotten, the hidden, the otherworldly. We want your stories to take us on journeys and adventures in the worlds only you can create; whether you make the familiar strange or the strange familiar, we know you will take us elsewhere. Be our tour guide through reality and beyond.

For this prize, we are accepting micro, flash, and sudden fiction, so we’re inviting submissions of stories from 100-1,500 words.

We’re thrilled to partner with Guest Judge Tara Campbell, who will choose three prize winners from a shortlist. We’re excited to offer the winner of this prize $3,000 and publication, while the second- and third-place winners will receive publication and $300 and $200, respectively. All entries will be considered for publication.

Good luck and happy writing!

Tara Campbell is an award-winning writer, teacher, Kimbilio Fellow, fiction co-editor at Barrelhouse, and graduate of American University’s MFA in Creative Writing. Publication credits include The Masters Review, Wigleaf, Electric Literature, CRAFT, Uncharted, Daily Science Fiction, trampset, Cotton Xenomporh, Flash Frog, Jellyfish Review, and Strange Horizons. She’s the author of the eco sci-fi novel TreeVolution, two hybrid collections of poetry and prose, and two short story collections from feminist sci-fi publisher Aqueduct Press. Her sixth book, City of Dancing Gargoyles, is forthcoming from the Santa Fe Writers Project (SFWP) in the fall of 2024. She teaches creative writing at venues such as Johns Hopkins University, Clarion West, The Writer’s Center, and Hugo House.

For this contest, Tara is looking for:

When I’m workshopping my own stories, I generally like to start with what I call “free-range feedback” rather than asking specific questions about, say, characters or plot or craft elements. Similarly, when I’m looking for a story that grabs me, I never know exactly how that’s going to happen. Maybe it’s an intriguing first line or an arresting image or a delightfully subtle, dry wit that runs throughout the piece. Often there’s a question (not necessarily a literal question, but a situation or conundrum) that compels me to keep reading to figure out how it’s resolved or not. I’m open to all genres, so if your piece has a hint of the speculative, that’s fine by me. Send me all your Elsewheres!

guidelines

- Your $20 reading fee allows up to two stories of 1,500 words or fewer each per entry-if submitting two stories, please put them both in a SINGLE document.

- We allow multiple submissions-each set of two flash/sudden stories should have a separate submission accompanied by a reading fee.

- Writers from historically marginalized groups will be able to submit for free (filled) until we reach our cap of 25 free submissions. No additional fee waivers will be granted.

- Please send flash/sudden fiction only-1,500 word count maximum per story.

- We only consider unpublished work for contests-we do not review reprints, including self-published work (even on blogs and social media). Reprints will be automatically disqualified.

- Simultaneous submissions are okay-please notify us and withdraw your entry if you find another home for your writing.

- All entries will also be considered for publication in Fractured Lit.

- Double-space your submission and use Times New Roman 12 (or larger if needed).

- Please include a brief cover letter with your publication history (if applicable). In the cover letter, please include content warnings as well, to safeguard our reading staff.

- We only read work in English, though some code-switching/meshing is warmly welcomed.

- We do not read anonymous submissions. However, shortlisted stories are sent anonymously to the judge.

- Unless specifically requested, we do not accept AI-generated work. For this contest, AI-generated work will be automatically disqualified.

The deadline for entry is September 15, 2024. We will announce the shortlist within twelve to fourteen weeks of the contest’s close. All writers will be notified when the results are final.

Some Submittable Hot Tips:

- Please be sure to whitelist/add this address to your contacts, so notifications do not get filtered as spam/junk: notifications@email.submittable.com.

- If you realize you sent the wrong version of your piece: It happens. Please DO NOT withdraw the piece and resubmit. Submittable collects a nonrefundable fee each time. Please DO message us from within the submission to request that we open the entry for editing, which will allow you to fix everything from typos in your cover letter to uploading a new draft. The only time we will not allow a change is if the piece is already under review by a reader.

optional editorial feedback

You may choose to receive editorial feedback on your piece. In your cover letter, please let us know which piece you’d like your editor to focus their review on. We will provide a two-page global letter discussing the strengths of the writing and the recommended focus for revision. Our aim is to make our comments actionable and encouraging. These letters are written by editors and staff readers of Fractured Lit. Should your story win, no feedback will be offered, and your fee will be refunded.

submit

by Margaret Adams | Jul 11, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

- First: Make sure your patient is safe. Hope that you gave the appropriate caveats when you told them that this visit is confidential, and make sure they don’t have any plans to hurt themselves or others. If they’re a minor, you may have to call Child Protective Services. If you didn’t properly warn them that this could happen if they disclosed this kind of harm, well, you are a huge asshole. Too late now. Let’s just hope you did.

- Once you’ve made sure they’re safe in an immediate, physical, legal kind of way, start saying the right things. Tell them it’s not their fault. Tell them they’re not alone. Don’t tell them, Hell, yours isn’t even the first rape story I’ve heard TODAY. When you get the urge to say this, lean in hard to the open-ended questions. What do you need? Offer forensics, advocacy, Plan B, antibiotics, therapy, water, tissues. Respect whatever they want. Don’t offer your own thoughts or opinions.

- After they’ve left, document. In your note, don’t use the word alleges. Don’t put “sexually assaulted” in quotes like you’re not sure. You would not write “patient alleges broken arm,” so don’t let the reflexive doubt of women seep in here. Don’t say simply that they were upset; describe instead the way their face didn’t move when they cried.

- At this point, even though you’re done, their story is alive in your skin. Your brain is a lurching mammal, the large kind, but the large kind that eats grass and dies easily. Notice this.

- Look down and realize that your shoes feel funny and that is because you now have hooves.

- Tell your coworkers you are leaving for the day. See if they notice if you look different. They don’t, or you don’t, it’s unclear.

- Go outside and lie on the grass. Don’t eat any of it, yet. Feel your limbs press into the ground. Try to loosen, let the earth do the work of holding your bones up. Your face feels furry. It’s hard to tell because your eyes are widely set now.

- Get up and run around. Run around and around and around. Avoid the road, but also poorly lit areas. It’s hard to do both, but try. The sun will set soon.

- If you are hit by a car, lie stunned on the side of the road, and know that the worst part is that if you live, you’re going to have to get up and keep going, eat more grass and have fawns and rub your rough fur on the sides of trees and probably, statistically speaking, get hit by another car, because deer are basically the pigeons of suburban America, and modern cars are pretty durable. Because that’s how society has dealt: we’ve made stronger cars.

- Run home. Your hooves clop on the walkway to your door. Swivel your eyes and hold your keys like a weapon until you put them in the lock.

- Sleep. Don’t remember how you got into bed. Don’t remember if you did or didn’t watch a few hours of television. Don’t remember if you drank water, or how.

- Wake up. Pull pants on over your human legs. Pat moisturizer on your cheeks. Go to work. Ask the questions. Say the right things. Follow the protocol.

by Skyler Melnick | Jul 8, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

There are six of them. No, seven. They cycle out of the tower and into the night, following their headmistress. Their headmistress wears a habit. The girls wear cloaks, cloaks to hide their hunger.

I cannot tell you where they are going, but I’ll tell you this: they are following a man—a man in a suit, cufflinks, and dress shoes, a man on a bicycle. They trust the man, but the man should not trust them. A pack of young girls is not to be trusted.

But a pack of young girls has to eat. They have not eaten in weeks. Their headmistress is in charge of feeding them, and she has not been diligent.

I don’t like when they have mustaches, one of the girls whispers. The hairs get caught in my teeth.

I’m too starved to care, says another.

This is a farce, says a third. He is old and ugly and drooping in all directions.

The girls cycle to the river. They eat the man, but he is not enough. They eat their headmistress, too. One of the girls coughs up her habit, the fabric damp and clumped and bloodied.

We’re gluttonous, says the girl, tossing the habit into the river.

We ought to drown ourselves, says another. As penance.

She wasn’t our mother.

She was like a mother.

Our real mother is gone.

Gone because we ate her.

The girls think back to their mother, whom they ate. She tasted better than anything they’d ever known. Like moonlight and shadows and cardamom. They’d had to eat her. Because of circumstance. Because of growing up. Because they were so so hungry, and their mother wouldn’t let them out of the tower.

We ate our mother! one of the girls cries. They’re in the river now, all of them, deep in remembrance, letting their bodies float downstream like dead fish.

We ate our father, too, another reminds them. And the baby. And the chef. And our lover.

Our lover was sour.

Our lover was curdled milk.

The baby was an accident!

Mother placed the crib right beside our bed, they remember. The baby practically crawled into our mouths!

Made our mouths taste of childhood, and the ocean, and millions and millions of years––

We had to swallow it.

The girls whimper, snivel, swallow, gulp down river water.

This hunger, they lament. Will it never end?

They sob, tears filling the river, raising it. The current pulls their bodies, down and down, sometimes underneath, but always back to the surface, until the water shallows, and the pack washes up on its shore, hands linked, eyes puffy.

I feel a lot better now.

Yes, they all agree, standing up, arms still linked.

We ought to find our bicycles.

And our shoes.

Our feet are going to be terribly dirty.

We’ll wash them when we get home.

Soon, the girls are skipping, hand in hand, some giggling, cloaks dry and billowing in the

nighttime breeze. They return to the tower and tuck each other into bed.

Was the bed always this small? they ask one another.

Was the tower always this narrow?

The girls clutch their stomachs, which rumble like thunder. They are not satiated. They move their heads side to side, taking each other in—the supple skin, the tender flesh.

by Emma Li | Jul 1, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

Transformation magic is easy. Gold into straw, carriages into pumpkins: the witch had done it a thousand times before. The man knew this. Or, perhaps more accurately, the pebble knows this.

The pebble sits in her pocket. Its companions are a dirty, wadded up tissue and a piece of strawberry wrapped candy. It has been in her pocket for a while now. It would not be there, had the man not wronged the witch.

They first met at the village tavern. She caught his eye, and they started talking. That night, he walked her home, and that morning, she walked him home. They began seeing each other regularly after that. They went on walks in the forest and talked and laughed for hours.

When they got hungry she would snap her fingers and transform leaves and twigs into fruits and cheeses, and they would go on talking. They soon spent all their time together.

In the mornings, before he left for work, he would make her breakfast and her favorite cold coffee with cream. In the evenings, after dinner, she would snap her fingers and transform water into whiskey or whatever he felt like that night. They fell into a quiet rhythm: one that the witch had always wanted and one that the man hadn’t realized he didn’t want. Sometimes, he tried to talk about it, but most of the time, they both ignored it.

The man started to have doubts. He began spending more and more time at work. The witch felt him pulling away and latched on harder. The man responded by staying away for days at a time. The witch caught him with a coworker.

They argued. Night fell. They argued. Dawn broke. They both said things they could never take back.

After he left, the witch sat at her table seething through tears. She thought about what she could do to him.

She could go with one of the classics and transform him into a tree. She’d heard of someone else, a warlock, who’d done that and chopped the guy up into firewood after. That wasn’t enough though, so he’d sent the logs to the guy’s family to keep them warm through winter. He even carved a branch into a toy for the guy’s children.

The witch considered her other options. She could turn him into a centipede— he was basically vermin already, after all — and she could keep him in a little glass terrarium, his legs scuttering away against glass too smooth to find purchase. He would never be able to leave her then. He wouldn’t be able to survive without her. He would be absolutely at her mercy.

Or what if she transformed him into marble and chipped him away bit by bit, slowly forcing him into a form of her choosing? She could carve him eyes but no mouth and force him to watch all their arguments, over and over again, so he would know that she was right and was wrong. She could do it. She could grind him into dust if she really wanted to. It’d be easy.

But that’s not when the man became the pebble. It isn’t as simple as that.

###

The man didn’t come back. She waited for him for days. A neighbor told her the man shacked up with the coworker. Of course, no surprise; he’d always been a rake. One day, the coworker had the gall to come and ask for the man’s stuff. The witch spat in her face and handed over a box full of ash.

Months passed. The witch’s rage simmered down into a bitterness thick enough to coat her tongue. She poured it into a cork-stoppered bottle but couldn’t stop herself from tasting it from time to time.

Years passed, and she partook of the bottle less and less. Eventually, it got pushed behind all the other jars of cumin and oregano, newt eyes, and frog toes. One spring morning, she found the bottle again while looking for a packet of strawberry candy. It was sticky with dust. She tasted it and found that the syrup had lost much of its bitterness, even developing delicate, floral notes.

She thought of the man for the first time in a while, and wondered how he was doing. A quick spell gave her the answer: a sailboat, a storm, followed by a memorial service.

###

The grass above the grave had shriveled into wilt. Rain left dark, dirty streaks over the headstone. Weeds had grown over the base.

The witch looked down and didn’t know what to feel, so she laced her fingers into the weeds and ripped. Dust shook loose from the roots. She tore at the dirt, leaving angry bald patches, followed by more meticulous plucking. Soon, the grave was neat and tidy. She pulled a wadded-up tissue from her pocket and wiped at the granite as best she could, clearing out the dirt that had settled into his name. With a snap, she transformed the dead grass into a bouquet of lilies and propped it against the stone.

For a long time, the witch stood at the foot of the grave. She didn’t try to think about anything in particular. Too much time had passed to remember all the details, and this emptiness filled her with the vague feeling like finding out a favorite perfume had evaporated into resin. She couldn’t remember what his voice sounded like or what his skin smelled like or even what his eyes looked like. Instead, all she could think about was how that glass of cold coffee looked on the counter, with leisurely swirls of cream mixing into the bottom.

Dusk brought a chill in the air. She began to walk away but paused with a sudden thought. She snapped her fingers and picked up a pebble from the grave. She tucked it into her pocket, where it sat next to a dirty, wadded-up tissue and a piece of strawberry-wrapped candy.

by Mikhaela Woodward | Jun 26, 2024 | contest winner, flash fiction

When I meet her, I say all the wrong things first.

Wind the beautiful.

Hair is yours.

Meet me nice.

Name I have.

All this to say: I will save the right things for last.

I recognize her from the wanted posters in the city where we are no longer allowed to speak. She is the woman in the pictures in every way and none.

A pleasure, she says.

Pleased, I say.

The desert howls grain into our ears. She finger-taps the top of her wooden staff, shakes a bracelet, hums an off-key tune. It’s hard to make a noise back, especially in front of her: the

sound thief. Alleged thefts: laughter, birdsong, the plush biting of fruit. They tell us to keep our sounds close to our chest, lest she find us in a dark street singing and take our music forever. You’re a bit quiet for an outlaw, she says.

Forgive me, I say. I am still learning to scream.

She smiles, and the glimmer of it looks so much like a fast-moving river that I want to run my fingers through her teeth. I step toward her. It is said if you speak into the sound thief’s mouth so closely that your lips are touching, you may steal it all back.

My canteen is empty, I say. Spare any water?

She obliges. She has to tilt her canteen very far to begin pouring into mine. Her eyes stir the blank horizons around us, and in the high noon sun, it is almost stunning how regular she is. How person. How me. How she curls a fist behind her back so I will not see her ripping at a hangnail.

The reward for her capture: a long and peaceful life of lemons and water.

You are wanted in the city, I say.

I am not sure why I tell her this. I am suddenly thinking very hard about the old blood crusted on my own worried nailbeds.

The sound thief spits froth into the cracked pale earth and says, I am glad. Who calls? The governor, I say.

That choke-worthy toe, she says. He acts as if I could steal whole sounds off the face of the earth. Imagine.

It is said the sound thief is not a woman of company. It is said the sound thief never quiets, fumbles, or breaks. It is said many things. I suspect most of them are not true.

When my father commanded her capture, I told him no. He reminded me of my duty as the cleverest of three sons. I reminded him that I do not care about thieves because I do not believe in property, to which my father smacked me hard on the back and growled into my ear: was I a man who wished to see his own father die of thirst or scurvy? Was I deranged, disobedient, suicidal?

I will give you the truth because lying is boring. I am not in the desert because I am stable in the head, obedient, or wish strongly to live. I am in the desert because I am a widower. I imagine the laughter of billions stacked neatly inside the sound thief’s chest like coins, besides other things that have gone: swallows, pomegranates, comedians. Those horrible comedy shows on the underground strip my wife loved so much. The smug smiles on the performers’ faces as they forced glee from our chests. Her hand hit the table when she laughed, bumping the ice cubes in my glass.

If I am so wanted, the sound thief says, why on earth am I dying in the desert? They are cowards, I say.

And you are not?

I am beyond fear.

Is that so?

The sound thief steps closer, scuffing the sand with her boots. For a second, I think I recognize her expression, how it lifts the skin above her wrinkles and winks at the sun above. The wide pores on her face grinning like little specks of moon.

It is, I say.

You must want, she says.

I do.

Name it.

I don’t remember.

Try.

I make a shuddering with my lungs. It sounds all wrong, like a bunch of bats banging into each other. I remember I have hidden the right words beneath my ribcage, for safekeeping. But they are so far deep, their shape unknown, like the name of my wife or the seed of a melon: small things wielding the threat of something colossally bigger. Seeds I used to swallow at mealtimes just to witness my wife’s deep superstitious concern for the guaranteed continuation of my life. You’ll explode, she’d say. You’ll grow into fruit. You’ll die. You’ll leave me behind. Please, just humor me.

She believed in a lot of things I didn’t understand. But here in the desert, I would gladly die by her slippery wives’ tale watermelon explosion if it meant remembering for one moment the exact way her laugh ricocheted across pools or her name: not what it was, but the way she said it when she said, Hi, my name is.

In the distance, the city is quiet.

The sound thief stands taller, with the posture of a battered lighthouse, and laughs darkly over her shoulder. I watch the direction the sound takes into the sky and feel it wing something open inside of me.

Recent Comments