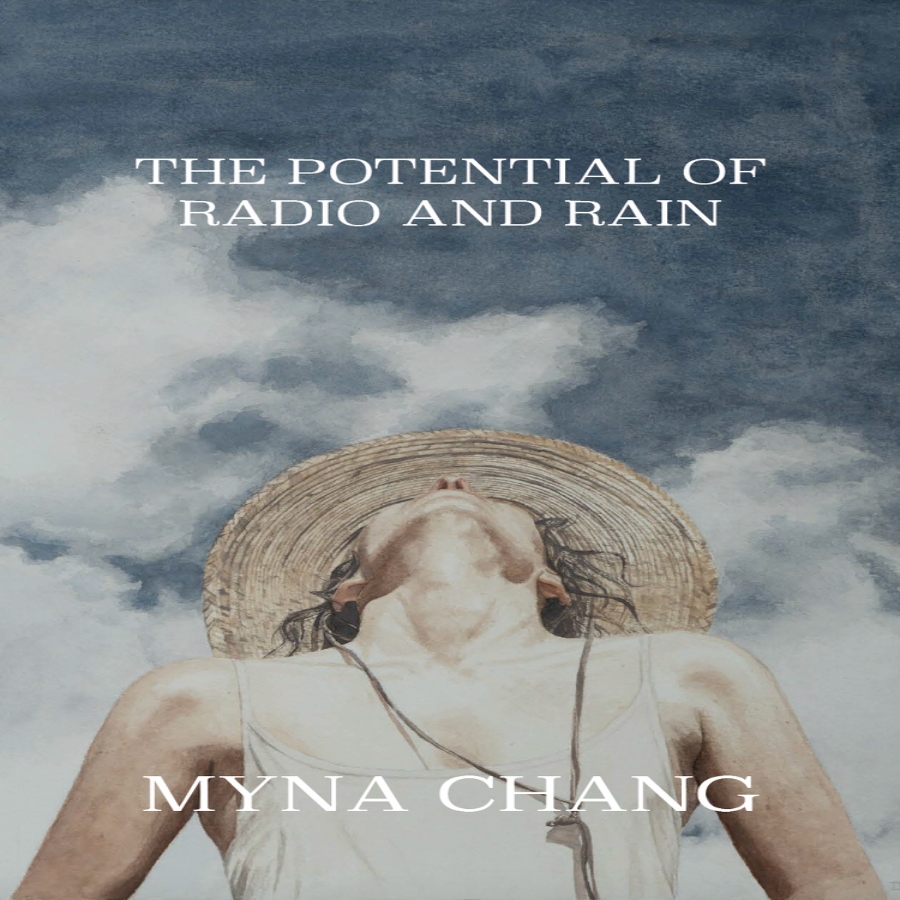

Myna Chang’s new flash collection, The Potential of Radio and Rain (out now from CutBank Books), is a revelation on the ferocity of human need set against the epic forces of nature. Her sentences snap as fast as a cyclone, whipping misfit characters across a prairie landscape to “resonate past the boundaries of this closed life.” Each flash clears away the stale air around human struggle, narrative storm fronts that offer new ways of understanding the world. Ultimately, Radio and Rain lures the reader out of the safety of the emotional tornado shelter in order to engage with each barometric pressure change. Chang and I discussed her lightning-sharp collection through a series of questions framed by storm systems, and her answers blew open the windows on her brilliant collection. ~Erin Vachon

EV: Your characters often yearn to transform into radical forms, like hybrid creatures or runaway storms: “If she had a choice, Grandma would say, she’d forgo Heaven and become a dust devil herself.” Could you speak about the relationship between transformation and freedom when writing your protagonists?

MC: I grew up in a tiny, isolated farm town in the Oklahoma panhandle, where most of us looked alike, and no one was allowed to be unique. Girls weren’t supposed to read science fiction, and boys weren’t supposed to paint landscapes. White girls weren’t permitted to date Mexican boys, and we certainly weren’t supposed to kiss other girls. We never divorced our husbands or started our own companies, and when we got old, we were expected to disappear.

My mother set a strong example by breaking some of these rules — by having the gall to find her unique happiness. Even so, I was very young when I realized I would never fit in.

I can’t go back in time to give myself a science textbook or encourage my friends to date the people they really liked. The best I can do, now, is grant my characters the freedom to live their fullest lives. Maybe that means the jackalope no longer has to hide her antlers or pretend to fit in with the rest of the rabbits. Maybe it means sprouting nightwings and flying away. And maybe my grandma can finally be as free as the wind, even if it is only through a story.

EV: In “An Alternate Theory Regarding Natural Disasters, As Posited By the Teenage Girls of Clove County, Kansas,” the young narrators push back against their surroundings, declaring, “Sometimes, a tornado is just what a town needs.” How did the unbiased violences of storm systems help you reconsider human trauma in this collection?

MC: First, I have to state that I do not believe a tornado is ever a good thing. But I am drawn to the idea of disruption, specifically the disruption of harmful societal systems. In “Alternate Theory,” the storm destroys wheat crops and property, but it also clears space for fresh growth. Teenage girls observe the shifting power dynamics as women shed abusive husbands, launch businesses, and discover unexpected love. The girls get to be the ones to pass judgment for a change, and they like it. They are not going back to the way it was before.

Growing up, I noted the incremental steps toward equality that helped me achieve a happier life than my grandmothers did. I thought we were on the right track! It’s been extremely disheartening to watch the de-evolution of our society over the last decade, especially in rural areas. So, this is my fantasy: a cleansing storm, a freeing wind, to help people see how the “norms” they cling to are often the very things causing their trauma and give them the clarity they need to build something better.

EV: I’m obsessed with the furious “power of the Binding Wind” in “Prairie Alchemy: Advice for the Newly Transformed,” which swells into a dizzy incantation for outcasts. What external limitations are you pushing back against in your work, structurally and thematically?

MC: In terms of theme, I love the idea of diverse people finding each other and building a welcoming community. I see this in my son’s group of friends—teenagers texting and chatting in games, sharing common interests, and recognizing the value in each other’s differences. These kids have grown up supporting each other, and they are vocal in their views of inclusion. They give me hope.

In “Prairie Alchemy,” my goal was to bind such expressions of inclusiveness to the structure of the story. I wanted to weave together a group of micros, with each thread focusing on a different kind of “misfit.” The finished piece is intended to be an interconnected tapestry, where the individual outcasts find safety and belonging in their newly forged community.

EV: Restless teenagers frequently take center stage in this collection, with “the melody of youth woven through the beat of your heart, like limeade thunder on a gear shifter.” What appeals to you about writing that young, whirlwind stage of life?

MC: I’m drawn to the sensation of potential and the lure of the open road ahead—both the brilliance and the folly of youth. Of course, I’m also haunted by nostalgia, especially when I hear an old song. “Limeade Thunder” came to me in a flash, in the parking lot of the grocery store (where most of my ideas take shape nowadays), when ZZ Top blasted out of the radio in my grown-up minivan. The guitar riffs brought back the taste of cheap beer and the discomfort of the long hot drive from our little town to the concert venue 120 miles away. It’s a good memory, but it is steeped in the bittersweet tang of “now I know better.”

EV: In “Hometown Johnnies,” the narrators curse the sky for holding back rain, saying, “We wanted to scream let go! but heaven wouldn’t unleash that water, held it fist-tight, just out of reach.” Your characters struggle against poverty and power, fumbling for release beyond their grasp. If nature showcases the gravity of being human, what hope can writing alongside its forces offer?

MC: In much of the shortgrass prairie, prosperity is intimately tied to weather. The cycle of drought can dictate the course of a life, so it feels natural to me to use drought as a metaphor for hard times. In “Hometown Johnnies,” I wanted to capture the commoditization of the poor and the young, the boys like my step-father, who worked summers in grain elevators or on oil rigs or served in the military in lieu of finishing high school. Jobs that promised a “good enough” wage to live on but that ground them up and spit them out, sometimes literally, were often the only option for boys in my hometown. They hoped they’d be the lucky ones who made it through unbroken, the same way we all wished the thunderheads forming over the Rockies would bring a sprinkle of relief.

Finding hope in the prairie isn’t always easy, but there are moments of beauty. My grandfather thought the morning sun was the prettiest thing in the world, and my dad wouldn’t trade a day in the wheat field for anything. Even though we had to drive two hours to see a doctor or buy a prom dress, we could count the stars in the Milky Way almost every night. Sometimes we did get lucky, and a few of us found our wings. The stories in this collection focus on desperation and stubbornness, but I think they also provide a glimpse of starshine and sunrise.

EV: One last fun question: if you could transform into any storm system yourself, what would you choose?

MC: I’d be that slow shower that comes on a May night when the moon limns the edges of the clouds, and you swear each raindrop is bursting with magic—because it is. Those rains come only once or twice in a lifetime, and you never forget them.

***

Myna Chang (she/her) is the author of The Potential of Radio and Rain. Her writing has been selected for Flash Fiction America (W. W. Norton), Best Small Fictions, and CRAFT. She has won the Lascaux Prize in Creative Nonfiction and the New Millennium Award in Flash Fiction. She hosts the Electric Sheep speculative fiction reading series. See more at MynaChang.com or @MynaChang.

Erin Vachon is a gender-fluid writer and editor, and a Recipient of the SmokeLong Fellowship for Emerging Writers. Their multi-Pushcart, Best of Net, and Best Microfictions nominated work appears in SmokeLong Quarterly, DIAGRAM, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Pinch, and Brevity, among others. An alum of the Tin House Summer workshop, Erin earned their MA with distinction in English Literature and Comparative Literature from the University of Rhode Island. You can find more of their writing at www.erinvachon.com.