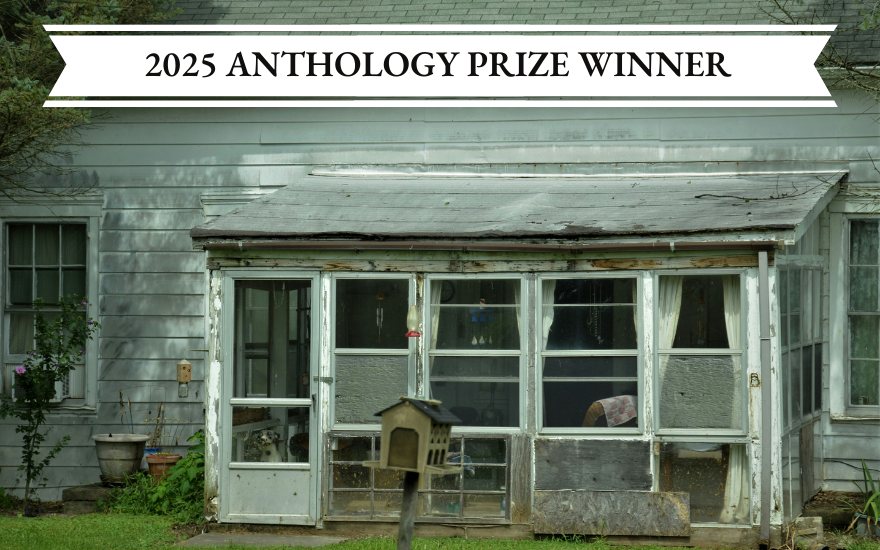

I was on our excuse for a back porch, no one ever put in screens, and it smelled like oranges under my finger nails. Jack lowered himself into the lawn chair next to the old Boy Scout cot I was on, looking up at the rain-stained roof with bits of tar paper peeking through. Old Spice tapped my nose. The guy loved Soap-on-a-Rope. He was nineteen and recovering from spine surgery. His sandy hair was matted around his significant ears. I didn’t get the details, but he had to go all the way to Syracuse to have the tumor removed.

“You counting nails up there or something?” Jack said.

“Just thinking.”

His voice was low like Dad’s. Slow like Mom’s. He was impatient with lugs like me and my all-time favorite. His current predicament seemed to give him a little more patience. Mom says he walked me around in the Taylor Tot when I was little.

I asked him once why he did it. “I loved riding in that thing when I was small,” he said. “And you liked to go, the word ‘go’ lit you up like a Christmas tree.”

“It’s not going to happen, kid,” Jack said.

“I can make it happen.”

I was going to Woodstock, it was a few hours away by car, and I could get most of the way by bus. I just turned thirteen, and my folks were, “hell no,” about it. It’s all I thought about, mostly so I wouldn’t think about Jack dying, not that anyone one said he would, but nobody said he wouldn’t either.

I would take the city bus from our neighborhood to downtown. Last year, while another brother was still in Vietnam, I took it all the way to Utica for an anti-war demonstration. Only twelve other people showed up, and I was the only one in Land Lubbers and Jesus sandals. That getup cost me ten nights of babysitting.

My folks thought the case was closed, my going to that “hippie-dippy weird thing,” as my father called it. I didn’t argue, counting on what Jack called, “benign neglect.” I had already tucked a pair of undies and socks in my book bag and would tell whoever was around on Friday, while the folks were at work, that I was going to the library downtown.

“You good, kid? I am going back in to take a pill and a rest,” Jack said like an ancient.

“Yep.”

I was scared when I got on that bus to Middletown. The creepy Charles Manson news, the war, and having never been farther than Oneida Lake. I had my map and a copy of Fire from Heaven. Twelve dollars in the right front pocket of my jeans and my return ticket in my bra.

A big, dark-haired girl sat next to me on the crowded coach.

“Where you going?” she said.

She hit the “you” hard, like in a gangster movie. Her eyes were so brown, and they disappeared when she laughed, and she laughed at everything. Like when I told her I was going to Middletown and then to Woodstock, and when the guy behind us asked why anybody from up here would go way down there to hang out with thousands of people who never took a bath.

“How old are you?” she asked.

“Fifteen.”

“Not.”

I shut up. She was probably only fifteen herself. But she had a different kind of life than me. I could tell she knew stuff, and I already loved her for that.

“How old are you?” I said.

“Fifteen, but it’s like in dog years. Why don’t you get off with me in Little Falls?”

I got off and we went to her place out in the country, a few miles from the station. Some old man in a pickup met her at the bus and drove us out to the house with faded orange paint peeling like a bad sunburn. The old man left without a word.

“Gramps never says much,” she said.

After we ate some chips with onion dip and drank some soda, we got on the bed in her room and talked. Her absent father, my sick brother, her dead horse and my brother in the war and the war being in the living room, her mother who is never home and always talking when she is, and saying things a kid shouldn’t even hear. We did stuff on that bed, with its quilt worn to the stuffing and stinking of Pall Malls and patchouli. She had slender fingers and no real wrists at the ends of her jelly roll arms. Her grief settled over me like fog on birches.

“I like the angles of you,” she said. “I dream of being what Gramps calls ‘lanky.’”

“Lanky isn’t you, it’s nothing special,” I said.

Then I wanted to go.

She called Gramps, and we rode back to the station. I got home before dark with my front pocket empty. I forgave her for that; twelve bucks wasn’t a lot to spend to get protected from your own silly self. I did some explaining, took my grounding of no buses for two weeks, and went to bed with a nose full of adventure.

That fall I contracted mono in the hospital after having my adenoids out. Jack had another surgery, and somebody brought the cot in from the porch and set it up in the living room next to the couch. We tried to do homework and watched the tube. We ate hot dogs and applesauce for lunch. The Miracle Mets won the World Series that October, which was worse TV than Lawrence Welk for a couple of diehard Yankees fans. I cheered for the Baltimore Robinsons (Frank and Brooks). Jack had bright red seams in his neck and holes in a head that was now held up by a contraption from Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory. There was trouble ahead for the both of us.