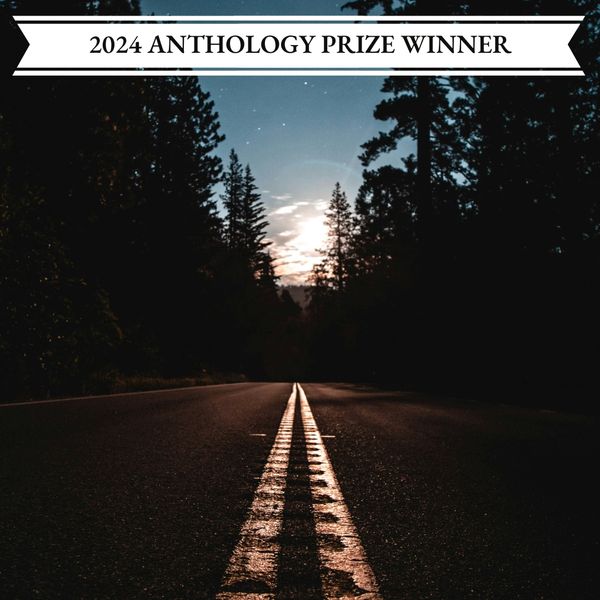

Look at their body language: Henry grips the wheel with his left hand while the other chops at the air. Marilyn stares out the window. They are driving down a two-lane road charred silver by the summer moon.

Without saying their goodbyes, they’ve left a house that heaves with life. Peek inside and you’ll notice sparkling teeth, crinkled faces, and hands fluttering cartoonishly. A drunk girl stirs a clutch of spaghetti into boiling water. Sodden jocks hold a séance around the sports highlights. In the backyard, clusters of teens mirror the patterns of stars above them. A boy throws up next to his car. A girl hides beside a whirring air conditioner to weep. And here—someone sits on the roof watching his cigarette smoke curl up toward the vestments of night. The scene resembles a coral reef, doesn’t it? Or a just-shaken snow globe. You might ask, where are the parents? Who watches over the children?

Back to the car, their conversation, Henry’s plea. He wants Marilyn to remain his true love when he leaves for college. He tells her this is the right thing, the only thing to do. Listen to the song spiriting from the tape deck—a divination of satellites and love. For her every objection, he offers the same reply: we orbit each other.

As they approach the hill that climbs out of the canyon, Henry stands on the gas. His sporty green coupe whines with all its might. On his yellow tee shirt, you might recognize The Great Wave off Kanagawa printed across the chest, the rowers digging into the face of that enormous, clawing wave, propelled forward by the inexorable coil of life inside them. Henry wants to fly over the crest and relieve Marilyn of the gravity that weighs her down.

She doesn’t enjoy this game. As Henry’s body leans forward for more speed, her fingers whiten around the grab bar next to her head. She turns her eyes forward, dark and defiant, bracing herself for weightlessness.

Now, let your attention wander up the road. A white car coming toward them bends around a curve. A woman whose face is filled with woe drinks from a Styrofoam cup. Her headlights paint the oak trees ghostly white, revealing the twine of their witches’ arms. Jeweled eyes flash in the darkness—a possum, a gaze of raccoons, the green glow of a coyote sauntering along the asphalt. As the white car approaches, the woe on the woman’s face disappears behind the full moon of her cup.

People in accidents say they ignored the signs. The angle of the headlights drifting toward them. The mesmerizing constellation of bugs across their windshield. The slow fade of the satellite song coming to an end. Henry remembers picturing a matador dancing right and then left. He replays the details for decades:

Two tires slide off the road.

His foot remains locked down on the accelerator.

The car jerks down the embankment like a hooked fish.

A tree bends out of the way.

He steers the wheel hard right.

He reaches for Marilyn.

A mortar explodes, and everything turns upside down.

Elephant.

Feather.

Elephant.

Feather.

Coins and cassettes and papers fly like confetti.

Birds, nesting for the night, scatter.

When they come to rest, the dangling side mirror reflects a sliver of moon. The metal wadded around them ticks and tocks. Henry reaches for Marilyn, but his arm won’t lift. She is curled up against her door, shutting him out yet again. Tiny roses bloom in his vision, and he begins to understand. It’s been a long day. He closes his eyes, if only for a moment.

Here’s a detail that’s easy to miss. A few miles up the road, in a house with one glowing window, Marilyn’s father, an oncologist, confronts the image of a tumor. A glass of ice water sits at his elbow. He is unaware that tomorrow, he will stand before a group of young people gathered in the ICU’s waiting room and tell them that the damage to the brain stem was beyond repair (“the” brain stem, not “her,” he realizes on that first anniversary as a thin keening sound splinters from his chest). The children will sit stunned by this impossibility until a girl (the one crying at the party) emits a squeak, triggering a wave of sobbing, shaking, and clutching that passes through them all. But tonight, he attributes his uneasiness to the careless ring his water glass reveals when he lifts it.

Now, back to Henry, strapped in a car that hisses its disappointment. He wears bits of glass like a crown. Blood blossoms scarlet across The Great Wave. Notice the flap of skin on his forehead that will leave a scar shaped like a smile. Watch his chest heave as an elephant’s foot steps down and a bird flaps up against its cage. Marilyn fell in love with the long black eyelashes that flutter in his dream, the broad shoulders and impossibly strong legs curled up beneath him. She fell in love with the books that mark the trail of their tumble, the metallic tapes filled with stubbornly eclectic music that flutter in the branches.

Our job is not to project, but should you picture these two as your friends, your children, as people you once knew, you can glide into this world. Here’s what I see: Henry’s body heals. He dives into his studies with blinders focused only on the future. He finds another love, fair and forgiving, and they create a family complete with a son and a daughter and years of meandering happiness. But on certain nights, when the world blazes like a pearl, he feels a shadow towering over him. He takes a deep breath, ready to surrender to its weight. Then his wife’s simple question, “What’s on your mind?” wakens the coil of life inside him, commanding him to paddle harder, paddle faster, and fly over the history that would otherwise swallow him whole.