by Aubrey Hirsch | May 2, 2020 | flash fiction

Amelia hates it when people call her Amy. Amy is her mother’s name, she tells them, and her grandmother’s name. And she is nothing like them. She is educated. She is a career woman. She wears pants and a leather jacket and has short hair because she is a flyer. And Amy and Amy? They are helpless wives of alcoholics, dragging their children behind them like designer luggage through the clatter of empty whiskey bottles.

She also does not want to be called Meeley anymore. It is an unfortunate nickname. It conjures images of undercooked oatmeal and apples that have sat too long in the blue bowl on the kitchen counter. It reminds her of the time she rode her sled off the roof of the farmhouse. She spent a moment on the ramp, angled toward the clouds. Then a long beat in the air—flying! It was the same stomach-dropping feeling as being at the top of her arc on the swing set, the moment when the chains go slack and you just fall. And then the hard smack of the ground. Her dress torn, her elbow bleeding, her molar turned to powder in her mouth. She shifted it around with her tongue. Rubbed it against the roof of her mouth. Mealy.

The students in her class called her “the girl in brown who walks alone.” That’s what they printed under her photo in the yearbook. Maybe she wouldn’t have been alone so much if any one of them had had half a brain. Or even a quarter of a brain. A quarter of a brain she could work with. But the girls at school were mindless idiots. They were just looking to get out of high school, get married, have baby after baby until they get a boy to carry on the family name, and die having learned nothing more than they knew in high school. Amelia filled a binder with images of women doing men’s jobs and doing them well: scientists, doctors, a mayor in New Jersey, a pilot. And look at her now. Ten world records under her belt. Now she is attempting her biggest stunt yet. The papers say she is the first woman to attempt to fly around the world. But she knows better. She is looking for more than good press.

Amelia really doesn’t like being called Mrs. Putnam. She’d rather be called anything else, including almost all of the cuss words. When the reporter from The New York Times captioned her photo, “Mrs. Putnam,” she was so mad she couldn’t see straight. George smiled a wide, beaming smile. “What do you think about that, Mrs. Putnam?” he said. She would have pitied him if not for the searing heat suddenly cloying at her brain. “I don’t know, Mr. Earhart,” she’d spit back. He struck her, the only time he ever did. She knew then she’d have to leave him. She rubbed her flushed left cheek. It would happen soon. She would board the Electra and never look back.

A.E. she doesn’t mind so much. She could make a fuss about society reducing her whole being to two letters, but she doesn’t. She concentrates instead on her flying. It is her escape. She takes Canary, her yellow bi-plane, up to eight-hundred feet where even the air she breathes feels different. Up there her busted sinuses magically clear and her headaches evaporate like dew in hot sun. No one is as fast as she. No one can follow her up this high. This is where she gets away. This is how she will get away.

Amelia is what she really wants to be called. Fred Noonan, her navigator, calls her Amelia. “Amelia,” he says, “we should start sending the signals now. We’re about three hundred miles out.” She nods at him, takes his hand. He calls in their coordinates as if they are still heading for Howland Island. But they are not. They are going to Gardner Island. It will be lonely there but beautiful. Fred is a marine man. He can make them shelter and find them food, fishing in the island’s big lagoon. She has nurse’s training. She will keep them safe and healthy. Her hair will get long. Fred will grow a beard. There will be no whiskey and no stupid girls and no grandmother telling her to wear a dress like a lady. Every morning she will wake up, naked as the day God made her, to the feeling of warm wind on her face and Fred’s sweet voice in her ear whispering, “Amelia.”

Originally published in Smokelong Quarterly

by Shasta Grant | May 2, 2020 | flash fiction

I heard my daughter was working at Laundry & Tan Connection and hoped it wasn’t true but when I went inside, the bells on top of the door jingling to announce my arrival, she was standing behind the counter.

“Jenny?” I said. She looked almost the same as when she was a child: hair still long and wavy, only now her face was thinner, her skin a deep bronze.

She looked up from a magazine. “What are you doing here?”

Coming here seemed like a good idea, since I was driving through town. That wasn’t exactly true, but it was only two and a half hours in the wrong direction. If I had turned around, I could pretend she wasn’t stuck here. I could pretend that in August she packed her bags and moved to Durham or Keene or Portsmouth with the others.

“You got laundry you need to do? Or you want to tan?” she asked.

She wouldn’t look at me and I couldn’t blame her. I wasn’t expecting her to throw her arms around me. The place was empty and quiet except for the whirling sound of a few washing machines. The owners of those soon-to-be clean clothes must have been next-door buying chips and soda, browsing the aisles of empty VHS boxes, the tapes stored behind the counter. Nothing much ever changed in this town.

“I’d like a tanning booth,” I said.

“Come on, you don’t really.”

“I’ve always wanted to try it.”

“Fine. What level do you want?” she asked.

“What are they?”

“You should start with level one unless you already have a base tan,” she said, finally looking at me. “Which you obviously do not. You want some lotion?” She motioned to the display of rectangular packets hanging from the ceiling with names like Chaos, Smokin’ and Hot Stuff.

“What do you suggest?”

The last time I saw Jenny and Shawn they were in middle school. We drove around town in my new car because there wasn’t much else to do. I thought the leather seats and electric windows would impress them. I wanted to take them to lunch but Jenny refused so we drove for a little while and then I brought them home to the trailer we had lived in together all those years ago.

“A lady came in yesterday, insisting on Chaos but she’d never tanned before. She came out with her eyes bloodshot and watering and said she felt high.”

“So you recommend Chaos?” I hoped to make a joke.

“If you want to feel high.”

The day I left, the kids sat quietly on the sofa and watched me pack my things. Their father and I had picked up that plaid sofa on the side of the road. Someone decided it wasn’t good enough anymore and pinned a sign on it: FREE.

“We’ve got a promotion,” she said. “Thirty-five percent off a bottle of lotion with a one-month unlimited package. But I don’t suppose you’ll be here long enough.”

“I deserve that.”

“You’re probably better off paying by the minute. You can stay in the level one booth for up to fifteen minutes. It’s three dollars and fifty cents for a full session.”

Saturday mornings, when we used to be a family, Jenny and Shawn would sit on that old sofa and watch cartoons while I made chocolate chip pancakes in the kitchen and smoked Newport cigarettes.

“Jenny,” I said.

“You want the lotion or not?”

“No. Can we go somewhere and talk?”

“I’m working. If you came here to see what a failure I am, now you know and you can leave. You know the way out of town.”

She closed the magazine and placed it next to a stack of Avon catalogs. I picked one up and turned it over, hoping not to see her name and phone number on the back but there they were. I sold Mary Kay when the kids were little. For six months I was a Beauty Consultant, which sounded important. We all thought I’d get one of those pink Cadillacs. I didn’t even make enough money to cover the cost of the starter kit.

In the end, Jenny used the makeup on her dolls, smearing Mystic Plum on tiny plastic lips. She’d set up a beauty salon in the living room with those dolls lined up on the sofa, waiting their turn. Shawn took the role of receptionist, bringing empty teacups to each customer.

“You’ll need to put these over your eyes,” she said, handing me a pair of funny looking goggles.

“I don’t really want to tan.”

“I know,” she said.

I remembered what she was wearing the day I left: a corduroy jumper with a white turtleneck. I had brushed her hair that morning and snapped her favorite barrettes in place. I held onto that image but it wasn’t enough. I wished I could tell her something beautifully sad about leaving: that I waded in an ocean of grief or that the loss rested in my heart like a heavy stone. I was happier after leaving and I couldn’t tell her that.

“So that’s it then?” I asked.

“I guess so. I need the goggles back.”

The bells chimed and a young man came through the door. He nodded at me and smiled at Jenny, handing her a can of soda. He asked if she’d be at the football game on Saturday and I saw a trace of pink on her tanned cheeks.

I came here to tell her it wasn’t too late, that she could leave this town too, but seeing her behind the counter, I understood she never would.

Jenny returned to reading her magazine. The young man unloaded his wet jeans and t-shirts into a metal laundry cart. My fifteen-minute session was up. There was nothing left for me to do but go. I stood outside, the little plastic goggles still in my hand, hoping she’d rush through the door to get them.

Originally published in Pithead Chapel

by DeMisty Bellinger | Apr 17, 2020 | micro

The telephone poles looked like crucifixes. I had the time to contemplate them, and that was how silent it was. We all remained inside like the person on the radio demanded us to. We looked out the large window, having pushed aside displays of shelved books and tea sets to see the large, male tiger, his testicles hanging noticeably from his crotch. From inside, we could hear the half growling, half purring noise he made. We probably more felt it than heard it. It was low. He paced.

“How long will he stay out there?” someone behind me said. I recognized the voice, but I had a hard time placing a disembodied voice to the person. I always had. I had a hard time understanding what was said without looking at the person who spoke. “Why hasn’t,” a woman asked, “anyone come to get him yet?” I went through the schedule in my head and remembered that Julie was the only other woman besides me working the floor that day. What I could think of to answer was that not all our days can be tiger free. After I had said it, I backed away from the window. Someone arrived in an armored car marked “zoo.” And also: some cop cars. An animal control van. I could hear the report from the tranquilizer gun. I thought of those savior-less telephone poles, the wires going to everywhere.

Originally published in WhiskeyPaper

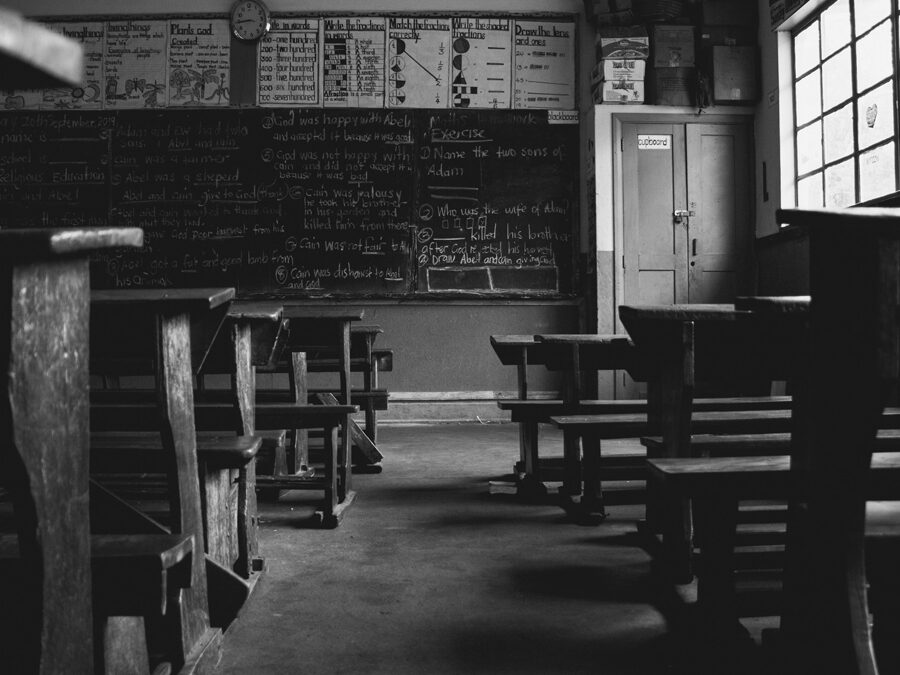

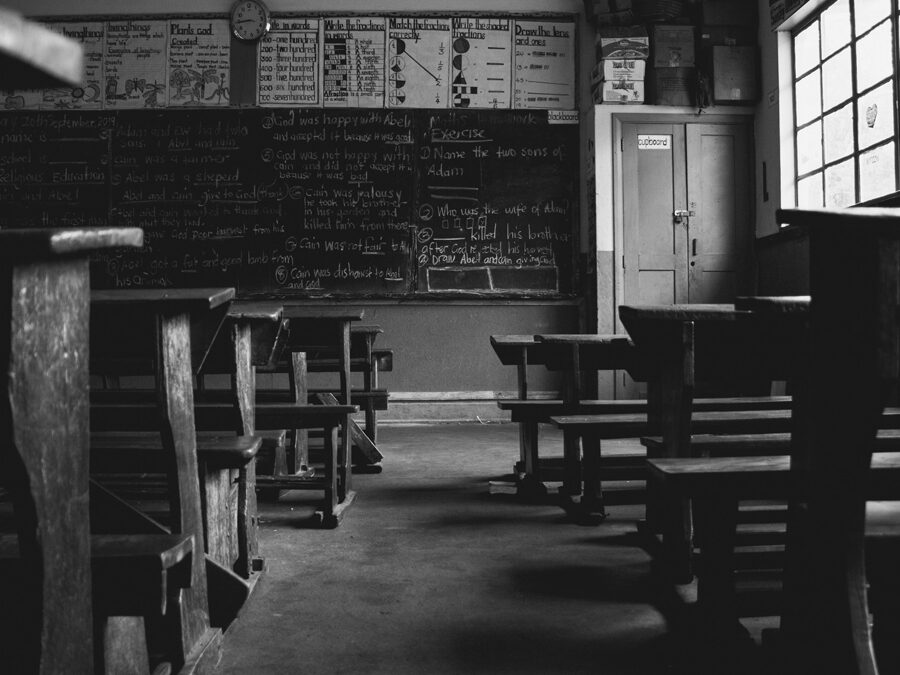

Photo by Sacha Styles on Unsplash

by Stuart Dybek | Apr 17, 2020 | micro

In summer, waiting for night, we’d pose against the afterglow on corners, watching traffic cruise through the neighborhood. Sometimes, a car would go by without its headlights on and we’d all yell, “Lights!”

“Lights!” we’d keep yelling until the beams flashed on. It was usually immediate—the driver honking back thanks, or flinching embarrassed behind the steering wheel, or gunning past, and we’d see his red taillights blink on.

But there were times—who knows why?—when drunk or high, stubborn, or simply lost in that glide to somewhere else, the driver just kept driving in the dark, and all down the block we’d hear yelling from doorways and storefronts, front steps, and other corners, voices winking on like fireflies: “Lights! Your lights! Hey, lights!”

Originally published in The Coast of Chicago

Photo by Carson Masterson on Unsplash

by Tara Laskowski | Apr 17, 2020 | micro

It was 10th grade, the year of Hurricane Isaac, which mowed down the mighty oak in the teacher’s parking lot, snapped it like a cinnamon stick and prompted Mr. Luckanza to teach us about dendrochronology, counting the tree’s rings. Grown-ups wanted to turn everything into a lesson.

It was the year the football team had a shot, and they introduced cheese fries into the cafeteria. We had to take English 10 and read dog-eared copies of “How Green Was My Valley?”, which everyone kept calling “How Long Is My Valley?” The economy tanked and my mom took a second shift at the late night diner. We all turned 16 and some of us got parties. The biggest one was Shannon Richardson’s, talked about for months because someone vomited all over her parents’ white suede sofa and she posted flyers on certain lockers looking for a confession.

It was the year people started losing their virginity, whether on purpose or not. Then, right before Christmas break, they found Mr. Luckanza in his car with a pistol in his lap and a shattered windshield stained red the color of those poisonous berries our parents always warned us not to eat. In the spring, a group of men came in overalls to finally take the oak away, chain-sawing it in pieces and tossing the hunks over the side of their pick-up. Even after they drove away I could still imagine rolling my fingers along the tree’s insides, the roughness of the bark and the tenderness of the inside, some rings small, some larger, some stained dark and hardened like a cancer, almost like it knew what was coming but couldn’t tell anyone until it was too late.

Originally published in The Northville Review and New Micro

Photo by AC TYLER on Unsplash

by Pamela Painter | Apr 17, 2020 | flash fiction

They don’t seem to be working, though up to a few minutes ago, she was filing papers. A man (whom we assume is her boss) sits reading a page at his desk, holding it beneath a green banker’s light. Her plump right arm is bent to encompass a generous bosom and her right hand rests on the edge of the open file drawer. Perhaps seconds ago she turned toward the man at the desk. Her face is vulnerable, intent. She is waiting. A piece of paper, partly hidden by the desk, lies on the floor between her and the man. We are led to believe that Edward Hopper is in a train, glimpsing this scene as he is passing by on Chicago’s El.

A voluptuous curve—perhaps the most voluptuous in all of Hopper’s paintings, almost to a surreal degree—belongs to this secretary in the night-blue dress in “Office at Night,” an oil on canvas, l940. What word, in 1940, would have been used to describe those rounded globes beneath the stretch, from rounded hip to hip, of her blue dress?

If it weren’t for that piece of paper on the floor, we might believe the museum’s prim description of this painting. It says: “The secretary’s exaggerated sexualized persona contrasts with the buttoned-up indifference of her boss; the frisson of their intimate overtime is undermined by a sense that the scene’s erotic expectations are not likely to be met.”

Indifference? Wrong. The man is far too intent on the paper he is reading—and he is not sitting head-on at his desk. He is somewhat tilted—toward the secretary. His mouth is slightly open as if to speak. His left ear is red. It is. It is red.

And what of their day? Her desk faces his in this small cramped office. He must have looked up from his papers to say to her, seated behind her black typewriter, that tonight they must stay late. Did she call her mother, or two roommates she met while attending Katherine Gibbs, to say her boss asked her to stay late? On other evenings, she would have finished dinner, perhaps been mending her stockings or watching the newsreel at the cinema’s double feature.

But here she is tonight, looking down at the paper on the floor. Was it she who dropped it? It is true that her dress has a chaste white collar, but the deep V of the neckline will surely fall open when she stoops to retrieve it. Or did the man drop the paper? Is she acknowledging this before she stoops over, perhaps bending at the knees over her spiffy black pumps, to retrieve the page? Another paper has been nudged toward the desk’s edge and shows a refusal to lie flat in the slight breeze blowing the window shade into the office. Other papers are held in place by the 1940s telephone, so heavy that in a forties noir film it might serve as the murder weapon.

Perhaps this story began at an earlier time. It might already be a situation, causing the young woman, just this morning, to choose this particular blue dress. We are all in the middle of their drama. She will bend before him. Someone will turn off the lights. They will leave before midnight. Perhaps it won’t turn out well. But for now her blue dress cannot be ignored.

Originally published in Smokelong Quarterly

Photo by Kamil Feczko on Unsplash

by W. Todd Kaneko | Apr 17, 2020 | micro

From the rear wall, Metalhead looks at the back of a girl’s head in History class. She is the only black girl in class and always sits in front, right next to the American flag. They are learning about Civil Rights, how one man had a dream and taught America about the content of a person’s character. Metalhead thinks about how he hasn’t said the Pledge of Allegiance since second grade—he just mouths the words to a song he once sang with his father on a car trip to Saginaw about dragons and smoking grass. After class, Metalhead will eat a slice of pizza and get high in the back parking lot. After school, his father won’t discuss layoffs at the auto plant, and when the family moves to a more remote suburb, there will be no conversation about white flight or a neighborhood’s changing hues as it breaks and corrodes. He won’t ask why his friends play air guitar along with Eddie Van Halen and Jimmy Page but never Jimi Hendrix because one day he will sell used cars and a woman he remembers from high school will ask to take a rickety Ford Tempo for a test drive. He won’t remember her name, but will recall how she once looked at him that way a child looks at an injured animal before learning that people aren’t supposed to reveal how they feel inside. He won’t let her drive the Tempo, guiding her to a car with a sturdier axle, a truthful odometer. This will happen decades after that girl in the front row looks back at the clock ticking over Metalhead’s desk. Her eyes fall on him for a moment before she turns back around. Metalhead places his hand on his heart and discovers it still beating.

Originally published by New South: A Journal of Art &Literature

Photo by Rubén Rodriguez on Unsplash

Recent Comments