by Amorak Huey | Oct 12, 2020 | micro

I’m scratching my name in the pew with my car key. I’m daydreaming about what it would be like to have a robot arm. Or a robot heart. I’m sitting while the believers line up for communion. I’m not invited, which is fine. The only flesh I want in my mouth is yours. I am a visitor in every room I’ve ever entered. I keep waiting for the pastor to say something about how we should treat each other, but all he ever talks about is how important it is to believe. To accept. To submit. It seems heavy-handed to say the next thing that happens is the passing of the collection plate but it is the next thing that happens. It’s too easy to be cynical. It feels like a trap. You consume the body and blood of Christ and return to your seat. I can’t remember whether you think this is literal or metaphor. I’m afraid to ask. I have never said aloud that I don’t believe in your resurrected savior or the magical land in the sky with gold streets and floating souls. I can get behind the love thy neighbors and the shall not kills and so forth, but not so much a magical man picking winners or losers based on how they spend Sunday mornings. The robot heart would be great, honestly. Unbreakable, resilient. I already know how this is going to end. You and me, that is. It’s going to hurt. Imagine, though. All those steel gears and steampunk valves, churning along, keeping the body alive without a murmur.

by Melissa Goode | Oct 9, 2020 | flash fiction

The kitchen lightbulb shatters above our heads. The filament burns red and fizzles to nothing. It is an explosion from light to black. We breathe hard in the aftermath, check each other for broken glass and he says to me, I can’t be here anymore.

#

Chicago-Read is still another five minutes away. I drive. In the passenger seat, his eyes are closed. The orange lit streets dissolve into the November night.

The radio plays, “With Or Without You”, his secret favorite song. It pulses in my fingertips. He says, don’t turn it off, and Bono sings that he can’t live.

I close my hand on his thigh and squeeze. Even through his jeans, he sears me.

#

The polished hospital floor reflects the fluorescent tubes and my headache throbs. It smells here of antiseptic and humanness.

At the front counter, I give his name, date of birth, psychiatrist. He stands beside me, carries his overnight bag. We could be checking into a hotel.

“I know it’s late,” I say to the nurse.

“Makes no difference here,” she says.

“24/7 service, right ma’am?” he says.

The nurse eyes him. “Right.”

A vent above us gushes arctic, stale air. He shivers inside his coat.

#

He is Every Man. His voice used for radio and television ads about male impotence, alcoholism, testicular cancer, bankruptcy, depression, suicide. He told his agent he needed two weeks off and had to battle for the time.

#

In his hospital ward, I kiss his lips and they are dry. He is already a patient. He says, go now please go, and shuffles to the bathroom, decades older.

In the parking lot, I cannot find our car. If he were here, he’d remember where we left it. The top level is empty. I move to the edge and before me the city shimmers and fizzes golden, silver, endless. The metal balustrade is perfectly scalable. I whisper-sing “Amazing Grace” and snag on wretch.

A plane roars overhead, low. It approaches O’Hare, certain, with calculated speed and angle of descent. Landing lights shine bright white. Wheels unfold from its belly.

#

Sunday morning. The tulips he bought are now overblown. Their violet petals fade, wilt and fall to our kitchen table, until only the gold-black stamens remain. Violet is the color of remembering him years after he’s gone. A petal drops and it is loud.

#

From the hospital, he phones, says, there is too much light here.

I say, it’s alright it’s alright it’s alright.

And it isn’t, I know.

#

Sunday afternoon, four p.m. The bleak-desperate-what-am-I-doing-with-my-life hour. I visit Barnes & Noble, sip full sugar Coke. My footsteps sound the word, dis-con-so-late. My high school students walk like this, weighed, shackled. Ir-re-deem-a-ble.

I spin the display of postcards and here is, “The Threatened Swan”, dated 1650, by Jan Asselijn. The swan’s wings are outstretched, luminous. It defends its nest of eggs against a stealthy black dog. The swan’s neck is arched, its beak open on a hiss. Feathers fly from its wings.

I buy the postcard, pin it to our fridge.

#

He calls me, says, I cannot hear my voice.

I say, I can hear you, honey.

#

Over radio and television, he tells me where to find help. He provides phone numbers, websites, tells me I am not alone.

#

We swim in green water in my dream, inside a deep cold pond. Gray wavy shadows fall on us. We are wholly submerged, suspended.

I wake and decide we were not underwater, instead we float on the surface. We are buoyant! We cannot sink!

#

For the first time since he was admitted, he agrees to see me. I bring him many of everything—Snickers, Twix, Doritos, Rolling Stone, underwear, socks, T-shirts—they could be things for a teenage boy.

I bring him the red blanket from our bed. His fingers trace the wide-white stitching around the edge.

He barely looks at me.

I regret it as I say it: “I traveled for miles in an aggressive Uber and the traffic is abysmal.”

Now he looks at me and I see the boy.

#

We watch television, slumped in his hospital bed. Our heads rest on his pillow, the red blanket pulled to our chins. I press my face into his neck, say, I should have brought you flowers. His skin is chilled, chemicals leach. I need to take him home, to a near-scalding bath, scrub us clean, make us taste of lavender, oranges, of Italy in the sun.

#

I want him to give me a show, his show. The slow one. I don’t care which way it goes, whether he starts clothed or naked.

#

A swan in Ireland stopped traffic as it hugged warm car hoods, mourning the loss of its mate.

He says, “Why are you telling me this?”

“Okay. No more fucking stories about swans.”

“Jesus. We’re not swans.”

I take his hand. “Why do you get to choose the metaphor?”

Here is his first smile in three weeks.

#

Here is my apology for this life—two million germs on the bathroom floor under my knees. His fingertips touch my hair and I don’t know whether he wants more or wants me to stop.

#

The television scientists have nothing good to say about the world’s population or the planet.

He says, “We’re all fucked.”

“It will get better.”

“Will it?”

He drops his heavy head to my shoulder. His living brain right here, cerebral circulation delivering oxygen and nutrients.

#

He sleeps beside me. The nurses have not yet kicked me out. The television plays a black and white movie—The Philadelphia Story. Katharine Hepburn and James Stewart dance together in the dark garden, drunk. He holds her close, his hand spread across her shoulder blades. Their steps are nimble, graceful, as they dance slowly around the rim of the pond and they do not fall in.

by Matthew McHugh | Oct 5, 2020 | flash fiction

Sometimes the name they give you is all wrong.

It’s really just meant to be a simple, two-word phrase to let people talk about a particular shade. “Honey, do you prefer Autumn Sand or Copper Slate?” or “Can I get two gallons of Alpine Storm?” “Is Harbor Mist available in semi-gloss?” We all have numbers, but you can’t use those in conversation. “I’m going to do the walls in 0973-016, the trim in 0975-732, and the wainscoting in 0984-283.” No, names are better. The marketing people figured that out long ago, and they were right. But they don’t always get it right with each one of us.

“Carrion Clay.” That’s my name.

I know.

We’re not even named by a person. Nobody looks at 3948-032 and says, “Hmm… this will be Desert Almond.” 0783-971. “And this, I’ll say is… Tropical Shadow.” It’s all done by computer. A word from Column A and a word from Column B. Gradations of orange are Tangerine Sunset, Florida Citrus, Honey Sherbet, and so on. Reds are Crimson Veil, Summer Valentine, Cherry Carnation, etc. Everyone seems happy with it. Everyone but me. Carrion freakin’ Clay.

I’d rather be just 0920-734, but I can’t choose how people perceive me. They pick up my swatch and make jokes. “World’s worst boxer!” “Name something you find at a preschool for vultures.” “Ooh, let’s do the door with this and the frame in Zombie Golem.” I’ve heard them all.

I am a microscopic shade off Sierra Amber and Twilight Sandstone, yet no one will ever let me near their baby’s room. No lowly office drone will hand-sponge me in their bathroom to create a faux marble effect, the one stroke of creativity that keeps their soul alive. I will never be the ambient hue a family subconsciously associates with the concept: home. Brushed Chestnut may. Even Mocha Gravel stands a chance. Not me.

Once… once, a woman browsing through a sample binder stopped on my page. She traced the edge of my eggshell latex finish with her fingertip and lingered on me. Her eyes took on the unfocused drift of one lost in imagination, and I knew she was picturing me in her hallway or bedroom. And, in that moment—that beautiful, accurséd moment—I dared to hope.

I dared to wish for that instant of consummation when she would step back, roller still in hand, and survey with satisfaction my final coating, a smudge of me just below the bandana on her forehead. And I would have served her for years (10 True-Guaranteed™), witness to her private joys and sufferings, until we both began to gray, old friends bound together deeper than any promise by countless hours in one another’s company.

This, and immeasurably more, I would have given her, had she but chosen me instead of Arizona Dusk.

Now, I simply wait. The third quarter sales figures will have reached corporate headquarters by now, and I am surely earmarked for discontinuation. I welcome it. Honestly, I do. Not everything that exists is promised a meaningful existence. I will pass away, literally, not having left a single mark upon this world.

If there is anything more, if there is anything beyond the misbegotten life I have known, let me be wiped clean and arrive fresh in that new place, my name forgotten, my number filed and lost, where I hope only to have the chance to shine.

by Amy Barnes | Oct 1, 2020 | interview

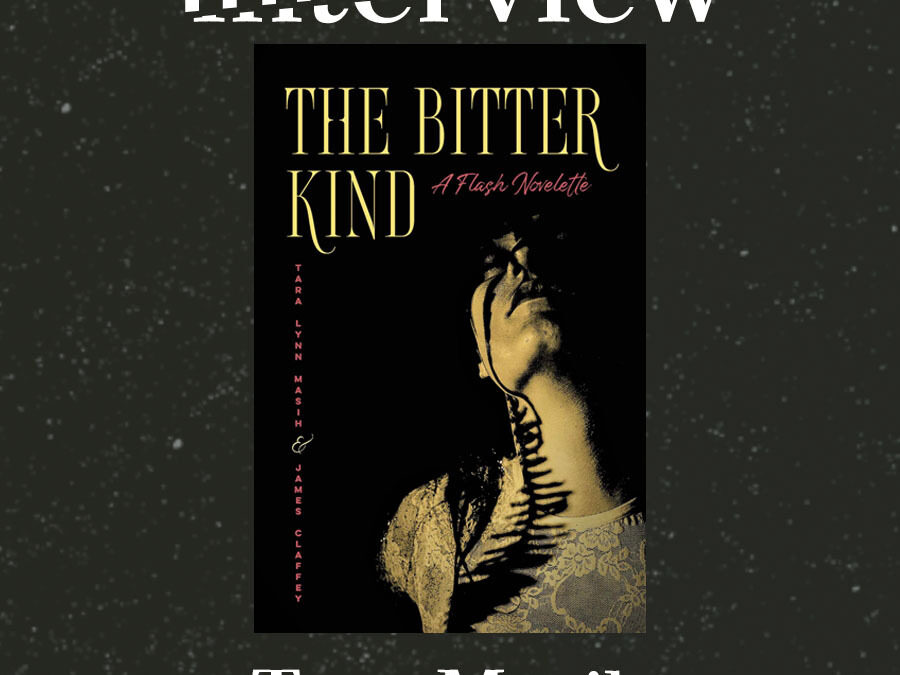

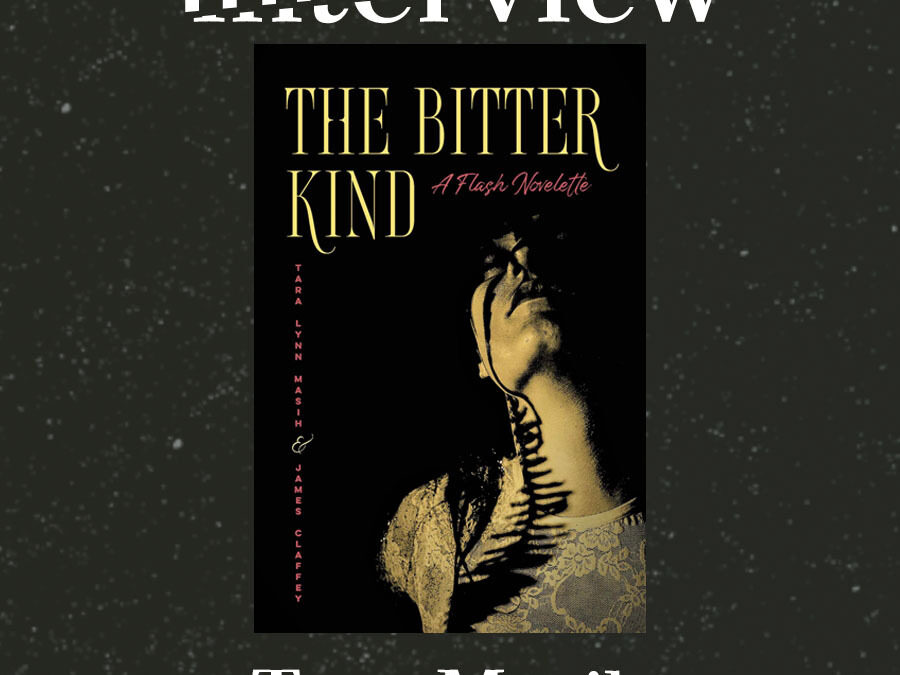

I’ve always thought of flash fiction as conversations where each exchange reveals or obscures, builds layers, introduces intimacy, teaches, grows curiosity. “The Bitter Kind” authors Tara Lynn Masih and James Claffey take that conversational flash level to a more expansive place in their novella-in-flash. Each individual flash connects with the next, chats with the reader through contrasting characters through time. The two main characters Stela and Brandy share their individual dreams and burdens; the flash novella format acts as a perfect setting for the seemingly improbable — a ship captain’s daughter and Chippewa orphan revealed through flashes about family secrets and ghost wolf hauntings. Through the skillful word and character creation of Masih and Claffey, readers converse with identifiable, yet unique characters. To learn more about the inspiration and process behind the novella, I interviewed Masih.

What is the significance of the title? Speak to the process of choosing it.

I’m glad you asked this, as we love the title. I pulled it out from James’s section. We don’t want to give too much away, but the bitter kind refers to a type of lemon. It fit so well with the lives of our two characters, their constant “battle” for love and the bitterness of what they face throughout their lives. I love titling books and often look to the manuscript itself for lines that resonate. I can’t recall the other choices, but this one we both loved the most.

How did you decide the length/novelette-in-flash form?

We began the project in flash form. We collaborated on a flash story (“Eighteen Crosses, One Madonna”) that combined two characters from our short story collections published by Press 53. When we decided to expand it, we knew we could come up with more material but did not want to make a commitment to a full novel. He was writing his debut novel at the time, and I was working on multiple book projects. So it made sense to write a novella. Well, it became a mighty short novella, and near the end, I stumbled on the term novelette, which fit our page count much better. We like the sound of it better, too!

What is the significance of the cover photo/design? How did you choose the artist to create it?

I’d rather the reader decide the significance of the cover photo, but we do want to recognize Ashley Inguanta, the photographer. We’re both big fans of her work. I’ve tried in the past to get her work on a cover and for one reason or another it didn’t work out, so we’re super grateful to Gloria Mindock at Cervena Barva Press for approving this image. We all just think it’s stunning. Dark and erotic and sensual and it draws you in. Makes you wonder.

There is so much encapsulated in this novelette that it feels like we get an entire novel. How did you determine the formatting? The date markers as “chapters”?

We had no idea how people would react to our little fun project. We really just followed the format we’d chosen for the flash story, which was to write alternate sections back and forth. We knew we’d use our flash skills, which often means lots of white space and big gaps in time. We had to ground the reader in the era it began in, so hence the use of dates. And we wanted to call attention to the most significant date of all, the one where they meet up, so that became Part 2.

There is something seamless as the reader moves between the two storylines. At the outset, the characters themselves seem disparate but you manage to connect them and focus on their personal stories. How did you find the balance and juxtaposition between the characters/the alternating between the two main characters?

It’s one part work and one part creative magic. We kept going on this project because we worked well together and these two characters just seemed to need more attention. And they worked well together on their own, but not completely. We each did many edits to make sure it felt authentic and that all details were accurate. As for the balancing act, it was pretty instinctive, though we both pointed out now and then when the other one had too much of a gap in the writing or when something didn’t make sense or was from the wrong time period.

A collaborator is a built-in, trusted, objective editor.

What research did you do to add authenticity to the stories?

I can only speak for myself on this one, but I did a lot of research on the Landless Indians in Montana (who I’m happy to report as of the beginning of 2020 are no longer landless) and Frontier Town, where Brandy works for a time. I have been to Montana and to the ghost town where Brandy also works, so it was easy to write about that setting. For Frontier Town, I was lucky to find an abundance of online history and images.

Ending on “for how long?” is such a poignant and yet, open-ended closure. How did you decide to end the stories at that point?

That’s a good question, as the original story actually ends differently. Again without giving away the ending, I’ll just say that sometimes as you are writing, you just know you’ve gotten to the last line, that everything that comes before that line has prepared you to write that last line. It doesn’t always happen that way, but when it does, it’s a mystical feeling. I had that when I wrote the final line. And luckily James felt it was the final line, too. He opens the book, I end it. Or, rather, Stela opens, Brandy concludes.

How long did you work on the novelette?

From beginning to end it was 8 years. We had to take breaks to attend to other projects. Hard to believe, but these kinds of books can take a long time to find a home. We tried the contest route first, which took over a year (we were lucky to place as a semifinalist in Conium Press’s chapbook contest), and as it wasn’t picked up, we began the general submission process, which again took well over a year, and we continually edited even into pages

Any other details to share?

I’d like to let fans of audiobooks know that Blackstone Audio will be coming out with an audio version, read by Siiri Scott, who does an amazing job. She knew just how to read our prose. We’re grateful Blackstone took this on as it’s an experiment for them, to publish something this short. And we are super grateful to Cervena Barva for the gorgeous paperback. And thank you to Fractured Lit for your interest. You guys are off to a great start!

BIOS:

Tara Lynn Masih is a National Jewish Book Award Finalist and winner of the Julia Ward Howe Award for Young Readers for her debut novel My Real Name Is Hanna. Her anthologies include The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Fiction and The Chalk Circle: Intercultural Prizewinning Essays. Where the Dog Star Never Glows is her collection of long and very short stories, and she’s published multiple chapbooks with the Feral Press that are archived in universities such as Yale and NYU. She founded the Intercultural Essay Prize in 2006 and The Best Small Fictions series in 2015.

Masih received a finalist fiction grant from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, an Inspirational Woman in Literature Award from AITL Media, and several national book awards including an IBPA Benjamin Franklin Award for her role as an editor.

James Claffey grew up in Dublin, Ireland, and currently lives in California. His collection of short fiction, Blood a Cold Blue, is published by Press 53. He is currently putting the finishing edits to a novel set in 1980s Dublin. His short fiction piece “Skull of a Sheep,” which first appeared in the New Orleans Review, is in W.W. Norton’s Flash Fiction International. His flash fiction “Kingmaker,” which first appeared in Five Points: A Journal of Literature and Art, also features in W.W. Norton’s New Micro: Exceptionally Short Fiction. “The Third Time My Father Tried to Kill Me” was published in The Best Small Fictions 2015, and he was a finalist in The Best Small Fictions 2016. His work has appeared in numerous journals and magazines, and when not writing he teaches high school English in Santa Barbara.

by David James Poissant | Sep 28, 2020 | flash fiction

That morning, Ted began buffering. One minute, he was Ted, coffee cup in hand, talking animatedly about this thing he’d just heard on NPR. The next minute, he was a rainbow-colored pinwheel, spinning. I’d never taken Ted for a Mac guy, so I found that part odd. If anything, he should have been that Window’s ring of circles. But, nope: a spinning wait cursor. That’s what he was. But only for a minute. Then, Ted was back, picking up where he’d left off, still talking animatedly about incarceration rates, or interest rates, some kind of rate of which he was very much against. Or for. To be honest, in the full minute Ted was a spinning, 2-D beach ball, I kind of lost the conversation’s thread.

If what I saw happen had, in fact, happened, Ted hadn’t noticed. We enjoyed our coffee and conversation, the way we do each morning, then rose and headed to our separate jobs. I went about my day bundling cellphone plans for small and midsize corporations, and, at five, I went home, kissed my wife, Allison, ate dinner, watched Game of Thrones, asked Allison to make love to me, settled for a hand job, and went to bed.

The next morning, Ted was back to buffering, and things were getting worse. Now, Ted started and stopped with great frequency, lurching in and out of sentences. I worried he’d spill coffee, burn himself, but, as with the day before, the pauses didn’t faze him. He emerged from each transformation gracefully, as though nothing had happened. And maybe nothing had. Around us, no one screamed. No one called 911. Ted smiled and talked, his mustache neat and trimmed, his wire-rimmed glasses as wire-rimmed as ever.

Still, I was unsettled. That afternoon, I left the office not having met my quota, a first in my two years with the company. At home, I couldn’t even watch Game of Thrones, and, when Allison resignedly offered a hand job, I said no. This thing with Ted, it was wrecking my days. So, I resolved to do something about it.

“Ted,” I said the next morning as we drank our coffee at our favorite small, independent coffeehouse—a coffeehouse whose name does not matter because it is a variation on the name of all small, independent coffeehouses, which is to say that its name is a play on words, like The Daily Grind or Thanks a Latte or Brewed Awakenings, none of which is the name of our coffeehouse but of which there must be several insufferable hundred in the continental United States—“Ted,” I said, “are you aware that, every so often—”

“Let me stop you right there,” Ted said.

“You know?” I said.

“The podiatrist says it’s not uncommon and that, if I keep wearing the medicated insoles, the odor will go away.”

“That’s very interesting,” I said. I waited while Ted turned into a pinwheel, then back to Ted, before I continued. “But are you aware that, every so often, you turn into a large Apple operating system spinning wait cursor?”

“Oh, that,” Ted said. “Yeah, must be a glitch in the Matrix.”

For a moment, I didn’t speak. I wanted to rise, to run.

Then, Ted laughed. “Naw,” he said, “I’m just fucking with you. My podiatrist says that’ll go away too. I’m on a couple of medications. Can’t seem to find the best dosage. Fucking HMOs, am I right?”

The next week, I saw more of them, the spinning pinwheels. At stoplights. At the office. Shopping for new blue jeans at the mall. Once, in a crosswalk, the woman ahead of me turned into one, and we collided. The feeling was roughly the equivalent of bumping into a very large marshmallow: soft, but springy, and with that ever-so-slight powdery feel left afterward on the fingers. I fell, picked myself up, and ran. When I reached the sidewalk, I looked back. The light changed. Patiently, cars drove around the woman while she buffered, and, once she changed back, the woman waited for the WALK signal, then crossed the street like nothing was amiss.

In these days, I found it hard to get work done. Even the hand jobs were difficult to appreciate. They weren’t like the hand jobs of our youth, when, dating, afraid to go all the way, we’d started with hands before working our way up to the deed. No, these hand jobs were passionless, as was my wife. Where had she gone, the girl I’d married, the Allison I loved? Days, we went to work. Nights, we watched TV. Weekends, we visited her parents or mine, or else we argued about money or sex, or about whether to have kids. In this, we were wholly unoriginal, which is to say we were wholly American. Which isn’t to say we didn’t have rich inner lives, that we didn’t want more, that we didn’t know that this, all of it, this American labyrinth of cancer and divorce and school shootings and guns and lottery tickets and guns and economic disparity and guns and soul-killing cubicles in the offices of large, soulless monopolizing corporations and guns was and is and always will be shit. We knew the maze, knew we were in it. We just didn’t know our way out.

And, so, we moved through the days, afraid, pretending not to be, and, in this way, we were very much American as well.

And there was so much to be afraid of! After all, what if I turned into one of those spinning things? What if I had already and didn’t know? Would someone tell me the way that I’d told Ted? Or was it a rule—unspoken, but firm—that one was not to go around acknowledging such things?

Another week passed, a week of breakfasts with Ted, a week of bad days not meeting my quota, a week of new blue jeans I’d thought would loosen with their wearing but turned out to be too tight, a week, hand job-less, of new and ever-worsening seasons of Game of Thrones (for, now, even the cast was turning into pinwheels, everyone waiting for Peter Dinklage, spinning, to say his lines).

And then it happened. The day came.

It was a quiet day. The morning had been good, Ted buffering only twice (a record for that week). After months of not commissioning out, I met my day’s quota of cellphone sales. Even the walk home from work was pinwheel-free. People walked the walk of happy people. Pigeons flocked in happy pigeon flocks. All, for a moment, seemed right with the world. And maybe it would be, I thought. Maybe this whole thing had been one short hiccup in an otherwise long and, hopefully, happy life. Maybe the pinwheel thing was going away and we, all of us, could go about our business like none of this had ever happened.

I was thinking this when I returned home to find Allison a large, buffering pinwheel in the entryway. Because of course things weren’t getting better, weren’t going away, because, of course, the problem had never been out there, had never gone beyond this very door.

I ran to Allison, grabbed her, bounced away. Where I’d run into her, the shapes of my hands and face were indents in the spinning disc. As I watched, the shapes pushed back, popped out, like a dented fender hammered into shape.

I cried. On the floor, head in my hands, I wept, and, when I looked up, Allison stood over me.

She didn’t say a word, but took my hand and led me to the bedroom. And we did not watch Game of Thrones. We did not turn on the TV. We went to bed. We made real love. And, for the first time in a long time, there was, as, once, there had so often been, not me and her, but us, a one, a we.

On a computer, the solution for the spinning wheel is called Force Quit. Command, option, escape: a trinity of keys that, clicked, dismiss an application from the world.

With people, it’s easier. You don’t need three keys, don’t even need a word to cut a person from your life. People quit on marriage all the time, step outside and shut the door on love.

Allison, I thought I’d lost you. And, maybe a few months there, I had. But some things are worth waiting for, which isn’t to say worth fighting for. Some things you can’t fight, can’t force. Some things you just wait out.

You sit at your desk. You hope. You squint.

You shut your eyes, praying that, when you open them, the thing you want, the person you love, will quit spinning, will reappear, and love you back.

Originally published in The Mississippi Review

by Francine Witte | Sep 25, 2020 | micro

in her bedroom like a secret, only we can hear it through the door. My big brother, Lou, took off with Ernesto, the boy with the neck tattoo of skull and bones, who picks up my brother in his Cadillac car, and they both will be gone for a week.

I scatter the little brothers and sisters outside. I tell them quick! it’s the ice cream man, can’t you hear him? Then I sizzle up a breakfast of hash and scrambled eggs, Mommy’s favorite. I crack open her door. She tells me go away, but I know she doesn’t mean it.

She is leaning herself over the beauty table. Midnight in Paris and red heart lipstick from the times she made herself up to look pretty for Daddy. That was before Daddy leaned himself over the dining room table and never sat back up.

That was when Mommy started crying and never stopped. For Daddy. For how are we gonna pay all these bills. And now for my brother, Lou. Who comes in, surprise! later that afternoon and not in a week like we were all thinking. He looks crushed and torn, his leather jacket ripped, a blue punch still on his cheek. He doesn’t explain, just goes over to Mommy and gives her the biggest hug. The both of them crying now.

That’s when my friend, Ceci who knows everything, calls me on the phone, tells me shush but she’s got a secret and I gotta swear I’m not gonna tell. She tells me Lou and Ernesto got into a fight on River Street. Ernesto got killed, and now they are looking for my brother.

That’s when my little sisters and brothers fly in, smacking closed the screen door that Lou keeps promising to fix. They chatter and giggle and pile into Mommy’s room when they see that Lou is home. He scoops them all up and squeezes them close. Mommy sits back and watches. A smile on her face for once.

Later tonight Lou will be gone forever. Running for the rest of his life. Maybe in time, a postcard, I’m okay, it will say, but I can’t tell you where. Wherever it comes from, Lou will be five days away. I will have to explain this to Mommy again and again as I sit there with her at her beauty table, as I try to draw her a lipstick smile, hoping that this time the tears don’t wash it away.

Originally published in Rougarou 2018

by Fractured Lit | Sep 23, 2020 | interview

What are your favorite things to write about? Those topics or items you can’t stop thinking about!

Hmmm. Tough question. Animals, musicians, and skaters tend to show up pretty often. I suspect all three get at some kind of expression that’s external to words and rooted in bodies. It’s funny though—there are the things you know you’re obsessed with and there are things that are surprising. I realized the other day that I write a lot about wallpaper, and while I do love old houses with funky décor, it never would have occurred to me that wallpaper was one of my things. I’ve never hung a strip of wallpaper in my life, and I’ve removed and/or painted over plenty. The subconscious has its own obsessions.

What’s your favorite point of view? Why are you drawn to this particular voice/perspective?

I don’t know that I have one. I’ve written in first (singular and plural), second, and third person. Honestly, I think the story has to determine its point of view. Each opens some possibilities and closes off others, and I really enjoy exploring those limits.

What’s your favorite craft element to focus on when writing flash? Is there an element you wish you could avoid?

I feel like flash, like poetry, relies on imagery and language. The fiction needs to have a kind of movement to it, but that movement isn’t always related to plot in a traditional sense. It can be a little more subtle—but, at the same time, I don’t want to avoid the idea of plot. I think it’s important to keep those traditional fictional elements in mind, even as the writers bend and play with those elements towards this genre.

How you know when a story is done or at least ready to test the submission waters?

I once heard Caitlin Horrocks say that a story is finished when the writer had given to it all she had to give and taken from it all it had to teach. She was quoting someone, but I have forgotten whom. That answer feels deeply right to me. I think too that I tend to feel excited about a story when it’s done and ready to share it with others. If I can have a few people read it before I send it out, that invariably helps. I take the feedback of trusted readers very seriously, even if I don’t always follow the advice they give. (At the end of the day, we’re still the writers and have to trust our instincts.)

When looking for places to submit your flash, what are your priorities for finding a good home for your work?

I try to read a lot of journals so that I have a sense of what they do. This helps me make sure that I send pieces to places that work in that vein. And I only send to journals I love. I would rather let a piece remain unpublished than have it in a journal I don’t respect. The good news is that there are now a ton of fantastic flash venues now.

What do you know now about writing flash or other forms that you wished you had known from the beginning?

Pam Houston visited our campus a few years back, and she said that, in flash, the conflict need not resolve but the image must resolve. It immediately struck me as true even though I had no idea when it meant, and so I started looking for the resolution of the image. I realized that in the flash I’d written that had been successful, the central image came to mean more or mean differently than it had when it was first introduced. Something about it had shifted in a way that made the story feel whole, in spite of its brevity.

What resource (a book, essay, story, person, literary journal) has helped you develop your flash fiction writing?

My first introduction to flash was in graduate school twenty years ago. Judith Cofer, my mentor, was a huge proponent, and she had us read Jerome Stern’s Microfiction: An Anthology of Really Short Stories. I still turn back to that book, but reading more contemporary work is also really important. There’s so much amazing work online now, and I love seeing writers experimenting with the form and trying different things. It’s a very pliable form, and even with its rigid word limits.

What’s your favorite way to interact with the writing community? Do you have any advice for writers trying to add to their own writing communities?

My very favorite is Writer Camp because there’s nothing better than talking with writers around a campfire, especially if you’re talking about anything and everything besides writing. But since Writer Camp is only a now and again treat for me, Twitter really helps me stay in touch with people and have that social space to joke around and play and encourage. I find a lot of new, cool work to read by following recommendations my friend’s post, and I’ve made so many friendships there that mean a lot to me. Oddly, I think the key to making Twitter work is not trying to make it work. If an account feels like marketing, I think a lot of people stay away. If it feels like a genuine person who is interested in other actual people, then Twitter can be really warm and welcoming.

BIO: Siân Griffiths lives in Ogden, Utah, where she teaches creative writing at Weber State University. Her work has appeared in The Georgia Review, Prairie Schooner, Cincinnati Review, and Booth among other publications. She is the author of the novels Borrowed Horses and Scrapple and the short fiction chapbook The Heart Keeps Faulty Time. Currently, she reads fiction as part of the editorial teams at Barrelhouse and American Short Fiction. For more information, please visit sbgriffiths.com

Siân’s new books:

Scrapple (novel):

The Heart Keeps Faulty Time (short fiction chapbook):

by Sarah Freligh | Sep 21, 2020 | micro

Kat goes missing again, but not really. She’s where she usually is—passed out, pants on backward, in the Wawa parking lot. Because this is her third or fourth offense, the dean of students summons her parents who drive eight hours through a freak April snowstorm. This is how much they love her, this is how much they want her to get well. You kids, her mother used to say, whenever one of them did something that baffled her. But there is no more you kids, no Kit or Kitten or Katie, only the Katherine in several official-looking documents the dean shares with her parents: Academic probation, mandatory counseling. Her parents bookend her, nodding agreement. The dean of students looks smug and shiny as an eggplant.

The therapist she’s sentenced to is bearded, upholstered in wool and corduroy. His office is windowless and dark with two armchairs that itch. He tells her to call him Joe, but she doesn’t feel like talking so they read magazines instead: psychology publications with covers that shout about big emotions and the power of boundaries, or old issues of Mad that bring back her brother John, how he’d named the family canary Alfred E. Neuman and tried to teach it to belch along with “It’s a Gas.” She wanted to play the record at his funeral but her mother said absolutely not, and had gone with hymns instead, full of God and mighty fortresses, that Kat pretended to sing along with.

Her heart is a stone. When she walks across campus she feels neon-lit: The Sister of the Guy Who Was Murdered at the Wawa. She is thirsty all the time.

Their fourth Friday, Joe hands her a box of crayons and some paper and asks her to draw a happy place, her idea of a heaven. She pauses for a second then sketches in tables, hanging plants, a birdcage in the window. A row of stools, three tiers of liquor bottles rising like a choir. Joe says, Birds? In a bar? “Wild canaries,” she says. Birds that sing sweetly, the way John sang in the shower, or when he harmonized on Happy Birthday. She hopes his soul flew up out of him when he was shot

Maybe open up the cage? Joe says, so she does. And, oh, what a wild bird can do when set loose indoors. Such madness. Such damage.

by Blake L. Bell | Sep 18, 2020 | flash fiction

Walls

Her nest is too tall by the time Molly realizes she can’t climb in. “I left my tools inside. Should I stop?” She asks her husband, who looks at the wall so hard the plaster cracks.

“Put some of those plaster shards around the outside, honey? Like a fence, you know?” Molly asks.

“Yes, love,” Greg says, grabbing the broom and dustpan for the smaller bits.

They’ve been in a bizarro routine for days. Her mother says she’s using art to heal her loss. She hates calling the dead lost. As if one day, while doing laundry, she’ll find that one she hasn’t seen in years.

Fallen twigs

Genesis is in twigs she finds fallen from pines in their backyard. She spreads them across their guest bed on top of a forest-green tarp. They are so stiff, so still. She needs to make them into something beautiful again. Something with purpose. Molly gathers them together in the center of the tarp and, before she knows it, she’s made a small, semi-circular nest. This feels right, Molly tells herself. I have something here.

Maternity clothes

Greg follows his Dionysus, hoping she can make a way out of what’s crushing her. Him. Them. He believes Molly can make almost anything. He buys her a new hammer and handsaw. She builds and builds—long, slender fingers cutting and weaving fabric from flowing gowns, tying twigs with elastic bands, and eventually, sawing branches from around their neighborhood. Each time she adds to the nest, she snaps a photograph.

Baby Blankets

Some of the last material Molly puts in the nest. One for each child, flown away, she thinks. “Maybe that’s a better word than lost,” she tells Greg as she braids the three blankets into the twigs and maternity clothes. Flown.

Photographs

She takes one last picture of the nest then develops her film. She orders the photos, conception to birth. A slow, steady witness to creation. She studies the structure that looms, that shadows her. The bigger the nest, the bigger the hole. She folds the photographs into thin rectangles and feeds them through cracks in the nest. It’s cavernous, sharp, and wooden. Inhospitable, she whispers to no one.

Hammer and Saw

Molly tells Greg they need to climb inside, just once. He takes pillows from their bed and throws them in the center of the nest, wide as the bed itself. They climb a small ladder. Greg gets in first, then helps Molly. Once inside, she hands him one of the tools she left. In this new world, it is only them and together, they hack at neighboring walls, rough twigs splintering, falling back in the nest, bursting them out.

by Meagan Cass | Sep 14, 2020 | flash fiction

As if covered in invisible glaze, her bread bakes pink. She buys new flour, new yeast, sends it into the oven a butter yellow moon. Still it comes out pink, a darker shade each time.

“It must be the water here. We’ll get filtered; don’t eat it,” her husband instructs, disappears back into his monograph.

This is the last move, he has promised. The department here is well-resourced, his position tenure track. She’ll find another gig teaching painting soon, how hard can it be in a college town. Now they can put down roots. Yet she feels as if she is watching her life from the ceilings fans, or carrying it on her back like wet cement. Out their bay windows, the sunsets are trying so hard across the soy-corn sky. She drifts back into the kitchen, closes the blinds.

Her bread is Barbie dream house pink, millennial pink, chapped lip pink. It smells just like her usual bread, as rich and warm as the loaves she’s made them in three different kitchens, in three different states. Before trashing it, she eats a pinch here, a slice there. At first it tastes like her childhood, like pool french fries after a swim meet, like her mother’s rose water perfume. Then it tastes like the sandalwood incense her college roommate used to burn, the girl she used to call her twin sister, a poet whose father had also left her, who also wanted to make a life around art.

Then it tastes of her first date with her husband, when she was still in undergrad and he was a grad student, the T.A. for her required Western History course, tastes of the penne vodka he recommended she order at the Italian place, and the mints he swallowed in the bathroom before kissing her at the Gillian Welch concert he’d gotten them tickets to as a surprise. How bowled over she’d been. The boys she knew never planned, just wanted to have drinks, “see where the night takes us,” played her pop punk in their cars.

The first date bread makes her body ache with hunger, as if consuming it does the opposite of its purpose, ignites new, hidden needs. She eats all of it, the last bread she will eat in this house. The next one comes out bloody, beating like a heart, slick and oblong like a baby with no face, like the child they will not have. She serves it to her husband as if it is a normal bread, places it on the table beside the roast chicken.

While he stares, she runs up to their bedroom, retrieves the bag she has already packed full of bathing suits faded by distant oceans, stiff, frayed brushes that just need a wash, a dash of rabbit skin glue, half-empty oils that are still good, and a hundred other things, all of it light on her shoulders.

Recent Comments