by Lori Sambol Brody | Feb 20, 2023 | micro

We took BART and then a bus down University Avenue, me in my jeans and black pleather jacket, as soft as the surface of my tongue, which means not soft at all, and you in your leather skirt, zipper down the side seam. Every man’s eyes snagged on your torn fishnet stockings. I don’t remember the band we were going to see, let’s say X or Lords of the New Church, but I remember you repaired the torn sleeve of your T by threading safety pins through the fabric. The velvet softness of the underside of your wrist when I dared to run my thumb over your pulse beating blue against your pale skin. Slow and steady, it didn’t speed up. In the club, someone rode a mechanical bull, and I wanted to hoist myself in the saddle like John Travolta, boot heels hooking onto stirrups, to show you how I could hang on, but, face it, I wasn’t wearing cowboy anything, just Vans and this cheap ass jacket with Husker Du’s logo painted on the back with Wite-Out. We drank Coronas bought with our older sisters’ IDs at the safe edge of the mosh pit, and the band played so loud, Exene or Stiv or whoever leaning into the microphone, your lips an O and the long curve of your neck as you drank. I wanted you to run your smooth tongue on every jagged lyric I yelled along with the band. The mosh pit a black hole, a maelstrom. A flailing arm, a stomping black boot, a fist pumping to the drum beat, a thrown elbow. You tried to smash your bottle to the ground, but I caught the heft of glass (your heart) in my hand before it could shatter. Then, you flipped your hair and stepped into the mosh pit, caroming off the bulk of a mohawked guy. You held your hand out to pull me in. Perhaps there was no riding bull, perhaps I didn’t wear the leather jacket that night, perhaps the band was Blood on the Saddle, the band you were really into that summer, but I remember this: when I didn’t clasp your hand, you moved away, one body in black among the other bodies, into the surging swirl.

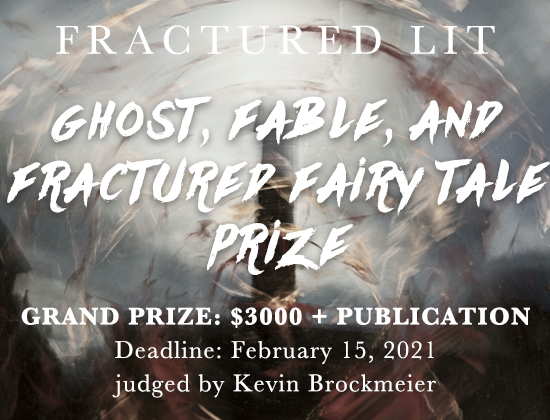

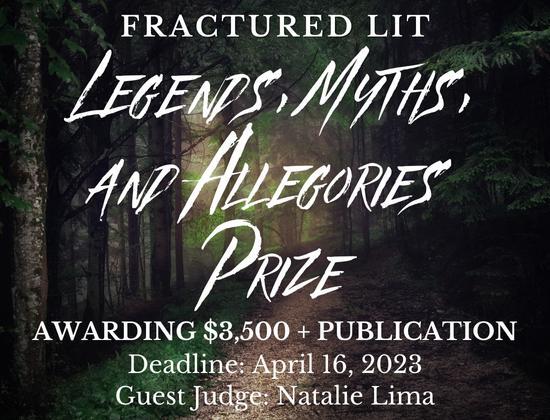

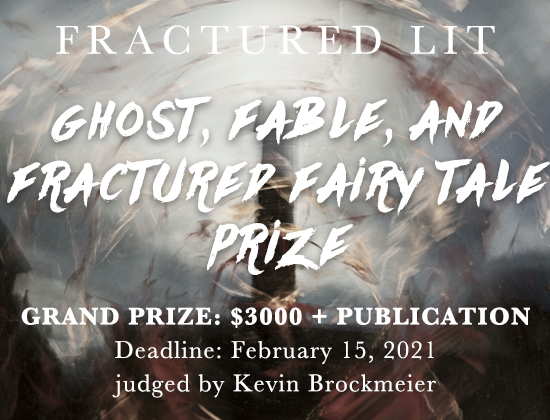

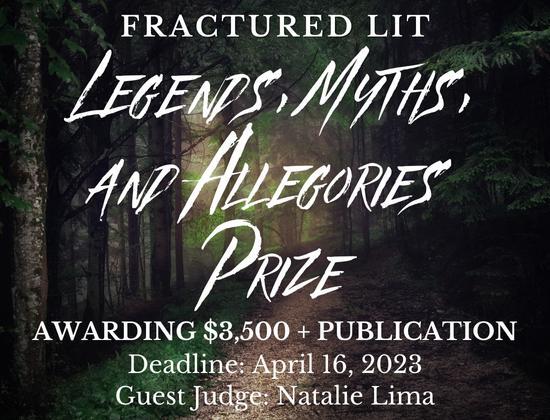

by Fractured Lit | Feb 16, 2023 | contests

legends, myths, & allegories prize

judged by Natalie Lima

This contest is now closed. Thank you to everyone who entered! We’ll have a longlist in around ten weeks!

Add to Calendar

submit

We’re excited to launch a new themed contest for our microfiction and flash writers. From February 20 to April 16, 2023, we welcome writers to submit to the Fractured Lit Legends, Myths, & Allegories Prize. (We would also love to see your ghost stories!)

Using these genre themes, we’re looking for stories that scare as much as they resonate, stories that help us discover the roots of desire and conflict, that shimmer on the page, that keep us reading and wondering long after the last period on the page. Transport us from the here and now to a new land of discovery, a fresh way of being entertained, a new way of embracing all of the ways we show our humanness. Fractured Lit is a flash fiction-centered place for all writers of any background and experience.

We’re thrilled to partner with Guest Judge Natalie Lima, who will choose three prize winners from a shortlist. The first-place winner of this prize will receive $3,000 and publication, while the second- and third-place place winners will receive publication and $300 and $200, respectively. All entries will be considered for publication.

Good luck and happy writing!

Natalie Lima is a Cuban-Puerto Rican writer raised in Las Vegas, Nevada, and Hialeah, Florida. Her essays and fiction have been published or are forthcoming in Longreads, Guernica, Brevity, The Offing, Catapult, Sex and the Single Woman (Harper Perennial, 2022), Body Language (Catapult, 2022), and elsewhere. Lima’s writing has been honored in The Best Small Fictions (2020) and noted twice in The Best American Essays (2019 and 2020). Her work has received support from PEN America Emerging Voices, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Tin House, the VONA/Voices Workshop, the Mellon Foundation, the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing, and the Hedgebrook Writers’ Residency. Lima recently joined the creative writing faculty at Butler University as assistant professor in the Department of English. She is currently working on a memoir and an essay collection.

GUIDELINES:

- Your $20 reading fee allows up to two stories of 1,000 words or fewer each per entry-if submitting two stories, please put them both in a SINGLE document.

- We allow multiple submissions-each set of two flash stories should have a separate submission accompanied by a reading fee.

- Please send flash fiction only-1,000 word count maximum per story.

- We only consider unpublished work for contests-we do not review reprints, including self-published work (even on blogs and social media). Reprints will be automatically disqualified.

- Simultaneous submissions are okay-please notify us and withdraw your entry if you find another home for your writing.

- All entries will also be considered for publication in Fractured Lit.

- Double-space your submission and use Times New Roman 12 (or larger if needed).

- Please include a brief cover letter with your publication history (if applicable).

- We only read work in English, though some code-switching is warmly welcomed.

- We do not read anonymous submissions. However, shortlisted stories are sent anonymously to the judge.

The deadline for entry is April 16, 2023. We will announce the shortlist within ten to twelve weeks of the contest’s close. All writers will be notified when the results are final.

Some Submittable Hot Tips:

- Please be sure to whitelist/add to contacts, so notifications do not get filtered as spam/junk: notifications@email.submittable.com.

- If you realize you sent the wrong version of your piece: it happens. Please DO NOT withdraw the piece and resubmit. Submittable collects a nonrefundable fee each time. Please DO message us from within the submission to request that we open the entry for editing, which will allow you to fix everything from typos in your cover letter to uploading a new draft. The only time we will not allow a change is if the piece is already under review by a reader.

OPTIONAL EDITORIAL FEEDBACK:

You may choose to receive editorial feedback on your piece. We will provide a global letter discussing the strengths of the writing and the recommended focus for revision. Our aim is to make our comments actionable and encouraging. These letters are written by editors and staff readers of Fractured Lit. Should your story win, no feedback will be offered, and your fee will be refunded.

submit

by Abigail Chang | Feb 16, 2023 | micro

but she is always multiplying, like a rabbit. In this version of the universe, Sally is only nine years old but she is always afraid, afraid of food poisoning, of losing her sense of smell, of screwdrivers that twist in the night. Evenings, she sits on her couch and crunches a husk of corn, filling the carpet with yellow shed, she scoops powder and fills a bowl to the brim before throwing herself down a chute as a form of prayer. Sally lives in a house with a window too small to climb through. There’s a snake in her boot, but she doesn’t know it yet. Sometimes there is a girlfriend beyond the window. The girlfriend’s fate and Sally’s are intertwined very closely.

Sally will find the snake when the storm hits.

Sally likes to writhe and sometimes even writes.

At midnight Sally will go blue all over and maybe even grow a beard.

(Sally is allergic to the night.)

The sad thing is if the universe had wrinkled differently all those millennia ago now Sally might be the snake, or maybe the girlfriend would be. For the girlfriend’s fate and Sally’s fate and the snake’s fate are intertwined very closely. Sally has peely feet and there is skin left over in the boot. The snake feeds on it because what else could it do? It grows larger despite everything Sally has done to shrink it. Outside the wind is picking up and Sally peers through the window, looks fervently, watches the grasses wave in the wind. She unzips an air mattress. She puts herself inside it, in and between the soft duckling down. Sally is not superstitious but still she puts salt all around her body in little white heaps. One day Sally will be forced to eat all the salt.

Things grow larger even when we don’t want them to.

When the storm begins to splutter, Sally finally bunks down. She sinks. She wishes. She eats an orange, one of the ones that rained from the sky, and thinks about everything she has lost.

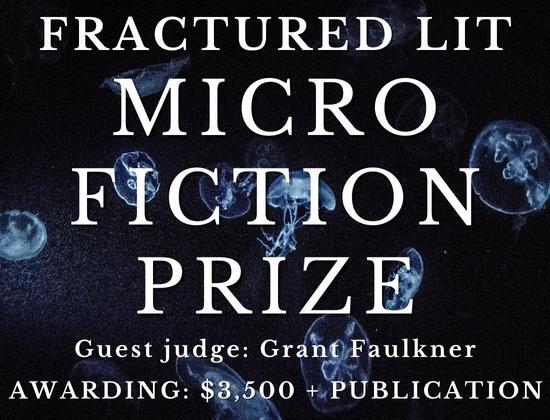

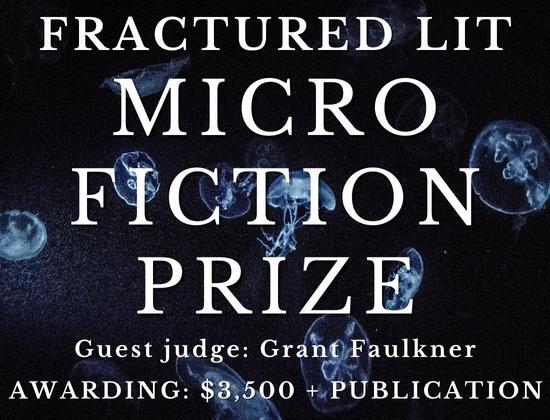

by Fractured Lit | Feb 14, 2023 | micro, news

First Place: Raising Rabbits by F.E. Choe

2nd Place: Burn It All Down by Karen Jones

3rd Place: Casual Pinch, 1992 by Alice Kaltman

- Raising Rabbits by F.E. Choe

- Will These Elevator Doors Never Open by Robert Clementson

- Hope by Rebecca Donley

- Aquatic Mammal by Shayla Frandsen

- Anchorite by Frances Gapper

- A Strange, Silent Relief by Ryan Habermeyer

- My husband said, keep baking bread by Jude Higgins

- Self-Solemnization by Marilyn Hope

- Burn It All Down by Karen Jones

- Casual Pinch, 1992 by Alice Kaltman

- Monday by Octavia Kuransky

- Bath by Bruce Maclachlan

- Cuckoo by Maija Makinen

- Drapes by Eva Nemirovsky

- Coexistence by Alberta Orcutt

- A Lovely Light by Alana Reynolds

- Pelican by Greg Schutz

- Hold Fast by Sam Thayn

- Relict Communities by Sara Wasson

- What It’s Like by Marie Watson

- Minnow by Jo Withers

- Mirror in the Ghost by Michelle Xu

by Emilee Prado | Feb 13, 2023 | flash fiction

Ann and Andy have a small, quiet apartment. They live tucked into a nook in a towering building, which is filled with other people who also live small, quiet lives.

Ann and Andy are made of biodegradable material.

We should note here that their names are not Ann and Andy; we just like to think of them that way: she inside him, and he a part of her. We do not know his or her real name, but that is okay. A name outlives its body; a name becomes an echo without a voice, a sign without referent.

Ann?

Andy?

Tonight, they are sitting together on their sofa inside their little apartment. They talk about big things and little things but only things that matter to them. They rarely feel compelled to have opinions about other people; they prefer to talk about ideas.

Andy does not want Ann to biodegrade. He knows that if the earth reclaims her, he will not be able to find her again. There is insidious material, Andy suggests, something that finds a way of lasting forever. Let us turn into plastic.

Ann does not want Andy to biodegrade, but she knows they should not turn into plastic. As plastic, they would stand. Maybe they would tip and fall. Maybe they would melt, but as plastic, of course, they would feel none of it. Nothing at all.

How will I find you once your trillions of cells and my trillions of cells don’t have voices to connect us? Andy wants to know.

I will make a way to call to you, and you will make a way to answer.

I will.

We will.

But we can’t go into the infinite unprepared, says Ann.

Ann touches Andy’s beautiful biodegradable forehead with her fingers. She gets up from the sofa and retrieves the knife they use for cutting fruit. She makes a small incision where the imprint of her fingertips still lingers.

Andy does not flinch. His gaze remains inside Ann’s eyes until it is his turn to take the knife and put it to her forehead.

Through the single trickle of blood bisecting their faces, they each pull out an invisible thread, one that can never biodegrade. Ann passes her thread to Andy, who takes it with his. He knots them together. He tugs to test the knot. They wrench and rip and pull and scream and decide to believe that the threads will remain connected.

It will hold, Ann says.

It will hold.

For a time, Ann and Andy remain together on their sofa while their biodegradable bodies continue to quietly deteriorate, but across the invisible thread they exchange tiny pieces of each other. For every one received, one is transmitted in return. Second by second, reciprocation continues.

Ann and Andy do not see our faces pressed against their apartment windows. We peer in from all sides. We scrutinize that invisible thread between them. Then we ravage our bodies, searching for our own.

by Fractured Lit | Feb 10, 2023 | interview

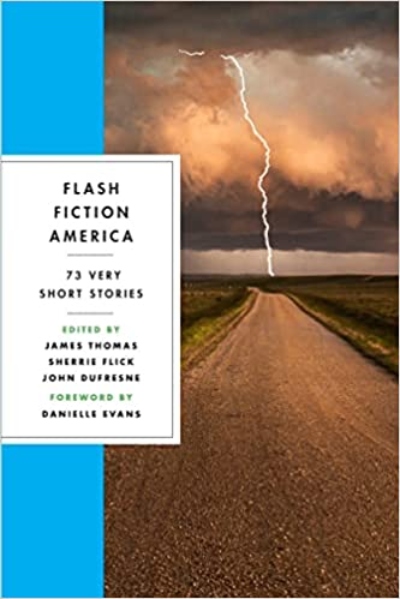

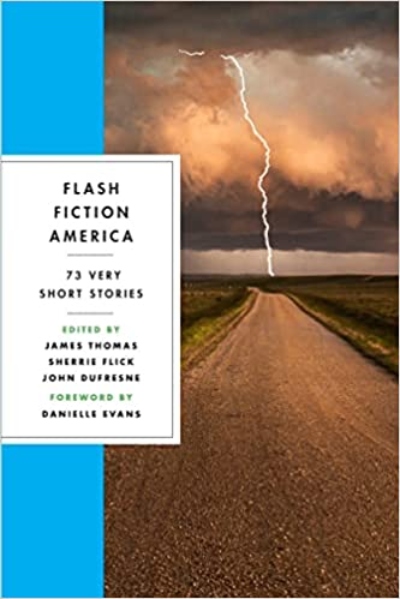

Co-Editor of the New W. W. Norton Flash Fiction America Anthology

The newest installment in W. W. Norton’s popular flash fiction anthology series, Flash Fiction America, will be released on February 14. Edited by James Thomas, Sherrie Flick, and John Dufresne, this edition contains 73 stories that “speak to the diversity of the American experience and range from the experimental to the narrative, from the whimsical to the gritty.”

Publishers Weekly says the book “brims with economical, well-crafted prose…Throughout, the authors craft distinctive glimpses of their characters’ worlds within the span of a page or two. [Flash Fiction America] showcases a multitude of talent.”

Co-editor Sherrie Flick took time from her busy schedule to answer a few questions. Thank you, Sherrie! And congratulations on another influential addition to the flash cannon!

—Myna Chang

Myna Chang: Norton has published a number of flash anthologies, dating back to the 1990s. How does this new anthology fit into their lineup? What are the strengths of this volume?

Sherrie Flick: Thanks Myna! We’re so happy to have your excellent story “An Alternate Theory Regarding Natural Disasters, As Posited by the Teenage Girls of Clove County, Kansas” included in the Flash Fiction America.

Yes, James Thomas coined the term “flash fiction” in the introduction to the 1992 anthology of the same name, and since then Flash Fiction Forward (2006), Flash Fiction International (2015), and Flash Fiction America (2023) have all been published by Norton. (There’s also the Sudden and Micro fiction series, which Norton has unrolled alongside these anthologies.) Editor James Thomas is the one common denominator across all these books.

Flash Fiction America is the first of the series to focus exclusively on American writers writing about America. FFA’s constraints are the same as the others—fiction under 1,000 words (mostly) and great crafted storytelling by both well-known and little-known writers pushing at the boundaries of the form.

One unique quality of this anthology compared to the others is how deliberately it explores place. The United States has such a varied landscape, and the people living within its borders are distinct and have such different lived experiences, we wanted to capture that as well as find great flash fiction.

MC: How did you become involved with Norton’s flash series? Did your experience publishing this book differ from your work as editor of The Best Small Fictions anthology?

Sherrie Flick: James Thomas asked me to join him and John Dufresne as the proposal for Flash Fiction America came together. He knew me as a contributor to Flash Fiction Forward, New Sudden Fiction, and New Micro, and I also served as an associate editor for Flash Fiction International.

I had some really specific ideas about inclusiveness that I think appealed to James, plus I’m really organized, ha, which is always a perk with an anthology that has so many moving parts. I’m also in the trenches, as it were, as I work as a senior editor for SmokeLong Quarterly. I’m not unfamiliar with reading thousands of stories and picking out a few that shine above the others.

The process for this book was much different from The Best Small Fictions 2018, where I served as series editor, along with guest editor Aimee Bender. Tara Masih founded the series in 2015 with the intent to showcase the best stories under a thousand words published the previous year in journals and magazines. With BSF, there’s a call for submissions with a deadline, and editors select a number of stories to forward—I think the limit was 5. So, we worked from a long, but finite, list of stories not selected by us, which were organized in Submittable and our goal was to find a solid longlist to forward to Aimee Bender for final selections. Of course, our timeframe to do this was a year.

We began Flash Fiction America with a clean slate. We didn’t have submissions to cull—we just needed to search and read and then narrow selections into packets which we graded in a four-year-long round robin of argument, assessment, and finally, selection. Our associate editors helped with reading packets and/or recommending both stories and authors to us. Flash Fiction America showcases research/assessment skills more than anything, from our side of things. We tried to look high and low—online and in hard copy—for the best pieces of flash published after 2000.

MC: What part of the process did you enjoy the most?

Sherrie Flick: Oh, I love spending hours researching. I have a background as an academic, and I’ve always loved to go deep into a topic. I’d spend days reading through a journal’s archives, not finding anything that worked for us, and then suddenly, I’d stumble upon a magnificent gem of a story. A story unlike anything we’d read to date. I would be so excited about it that I had to send it immediately to James and John.

I really like every aspect of creating a book—selecting the stories, ordering the stories, copyediting, arguing about everything—including hyphens. I’m that nerd. I love all of it.

MC: How would you describe the evolution of flash since you began writing and editing? Has the essence of flash changed over time? Are you seeing any trends? What do you hope to see next?

Sherrie Flick: Tara Masih has written a fantastic history of flash fiction for the Introduction to The Rose Metal Press Guide to Writing Flash Fiction. I would recommend that everyone read it in order to understand the form’s history in this country and others.

Since I started writing and publishing, what we called at the time short-shorts, in the late 80s, I think the form has become more commonplace. I see fewer arguments about prose poems vs flash fiction. I see more interesting discussions regarding compression and craft. There are more workshops and classes. There are more places publishing flash—even The New Yorker has a series now—and I see pieces of flash frequently popping up in story collections that have more traditional-length stories in the mix.

Trends. At SmokeLong we’re getting a lot of stories written in second person. I’m not the biggest fan of second-person stories, which is probably why I immediately noticed this trend. My hope for the future is that flash writers go deeper into third-person narratives where, in my opinion, more complex crafting can happen.

MC: Now, let’s talk about your own work. You’ve found success in so many literary avenues. What are you most excited about right now?

Sherrie Flick: Thanks Myna! I’m working on putting together my third story collection. I’m most excited about this series of bear stories I’ve been writing. They started during the darkest days of the pandemic and have expanded from there. Stories about bears acting like humans, humans being mistaken for bears, a bear carrying a heart and wearing underwear in a Budapest train station (“Breaking” in Booth), bears in the foreground, bears in the background, one guy wears a mail-order bear suit as he works as a home inspector. Friends keep forwarding me real bear stories and videos, so it has been great fun to draft and revise these. They will be a thread in the manuscript that will also have non-bear stories in it. One can only take so many bears.

MC: What’s next for you?

Sherrie Flick: First, promoting this anthology. Next, I’d love to work on another anthology. I’m interested in writing a craft book. Writing more stories, essays, teaching, and editing.

SHERRIE FLICK is the author of a novel and two short story collections. Her collection, Thank Your Lucky Stars (Autumn House Press), is now an audiobook. Adina Verson performed her story “Heidi is Dead” from Whiskey, Etc. (Autumn House Press) for NPR’s December 2022 Selected Shorts. New work appears in Ploughshares, New England Review, and Pithead Chapel. She is a senior editor at SmokeLong Quarterly, served as series editor for The Best Small Fictions 2018 (Braddock Avenue Books), and co-edited Flash Fiction America (W. W. Norton).

MYNA CHANG (she/her) is the author of The Potential of Radio and Rain. Her writing has been selected for Flash Fiction America (W. W. Norton), Best Small Fictions, and CRAFT. She has won the Lascaux Prize in Creative Nonfiction and the New Millennium Writings Award in Flash Fiction. She hosts the Electric Sheep speculative fiction reading series. More at MynaChang.com or @MynaChang.

by Stephanie Yu | Feb 9, 2023 | flash fiction

1.

You are six, and your brother is four. The sun is so bright compared to the lush New Jersey canopy you are accustomed to. It makes the world appear technicolor and elongated. You go through “It’s a Small World,” and something about the unease of Florida burrows deep inside you then. The mechanical theater makes you feel hollow and alone. Not a human soul around aside from your brother screaming “wǒ yào huí jiā!” over and over as the water surrounds you, easing the mechanical boat off its mechanical track.

2.

You’re on a Habitat for Humanity build trip for spring break in Fort Lauderdale. You had been the president of your chapter in high school, so joining the college initiative seems like a natural progression. The students who sign up are a mix of pseudo-Christian nerds majoring in engineering and fraternity bros listening to The Killers’ Mr. Brightside on repeat. One of them tells a story about a girl who tried giving him a blow job by literally blowing on his cock, and you laugh with all your teeth, like you know any better.

You’re all made to sleep on the floor of a church multipurpose room with about twenty other university youth groups. There are only three bathroom stalls. Predictably, the toilet paper runs out. One of the frat bros threatens to book a hotel nearby for him and his stoic girlfriend. You had only ever used your credit card to buy textbooks, so the concept of buying your way out of a shitty situation is novel to you. That you don’t have to bear sleeping under the tent of your damp bath towel, catching the waft of other people’s turds.

In the morning, prayer circles have sprung up outside the church like fungi. Secular being the general vibe of your group, you all snigger at those bowing their heads and clasping their hands together in expiation. An intimacy you don’t even share with your own family.

You build houses but don’t have any of the proper tools. The homes go up crooked, hung together by mismatched nails. One of the group leaders with a box beard and a receding hairline thinks it’s fun to drive the back way to the building site, which is torn up with potholes. He takes them at full speed, and the car bounces in the air like a jet ski skimming the tepid Florida ocean. Some of the people are scared, but, to you, it’s exhilarating. Your seatmate looks like he’s about to vomit. You grab his hand. Your eyes meet, and your teeth rattle and clank together.

3.

You’re meeting your now boyfriend’s family for the first time. They literally live on a golf course. There is netting surrounding the back of the house to prevent balls from penetrating the glass windows. The spongy perma turf of West Palm Beach smells loamy and rich with pesticides. The house’s shutters are seafoam green.

The reason they’ve moved from Schenectady is his father, who crushed the top two vertebrae in his neck a decade ago in a freak boogie-boarding accident and can no longer stand the cold. He moves around by blowing through a straw and speaks like he has something pressed against his chest. You bought him a coffee table book about Paris as a host gift, which is a terrible idea, as he can’t use his hands. He is still gracious about it, which makes it all worse.

You sleep in the guest room where your boyfriend’s mother keeps her doll collection in a glass case with a mirrored backsplash. About half the room is taken up by this display case, and the other half by Container Store storage units holding more dolls in more boxes. She acknowledges that this is creepy, but doing so doesn’t make it any less so. You dream about her coming in while you’re sleeping to brush out their hair.

Your boyfriend grills swordfish steaks and peaches but adds no seasoning. You all eat together in the muggy back porch, impervious to golf balls. You drink out of enormous plastic tumblers embossed in patterns of ocean waves. Every time you take a sip, you feel like the drink will come spilling out from the sides. You learn they are meant to be this way, to contain ice but eradicate condensation. When you open the screen door to excuse yourself to the bathroom, the air conditioning hits you from above, and you feel very small. You’re wearing a terry cloth skirt that your boyfriend had picked out for you. It’s the color of toilet bowl cleaner.

One night, they decide to order Chinese takeout from their usual place, Golden Dragon. When the delivery woman arrives, she looks at you and smiles. Lingers. Bows slightly in your direction. You nod but don’t say anything, like you’re being held hostage. Your boyfriend’s mother makes the comment that they’ve never done that before in all the times they’ve ordered from there. You think about the geisha doll she has in the guest room, porcelain face, painted-on lips, eyes penetrating you from behind the cellophane.

4.

The last time you’re in Florida is for a wedding. You decide to go for a hike in the nature preserve behind the venue—a golf resort, naturally. You need to escape the decor that your brother says looks like the ending from Scarface. The trees are full of animals, and their exhalations ring in your ears. The mud puckers around the satin of your shoes. In all the times you’ve been to Florida, you’ve never understood the barbarity of it. How the vastness of its churches and the sterility of its homes is a rebellion against the wildlife that lies in its wake, crawls out from the swamp, drags you through the mud, stings you at the ankles and watches you writhe, your feet getting tangled in a veil that—as it turns out—is far too long.

by Michael Czyzniejewski | Feb 6, 2023 | micro

The air raid sirens sounded and my brother Bruno scrambled, demanding to know where my basement was. I didn’t have a basement and informed Bruno it was the monthly test, that there was no attack, but Bruno started stacking canned goods, rifling through cupboards. I told him it was ten a.m., second Wednesday of the month, but Bruno only looked more convinced, said this would be the ideal time for an attack, everyone thinking it was just the test. His arms were full of soup and chili and vegetables, and he said I should coral the dog and all my bottled water, that we could come back up for the radio and first aid kit if we wanted to risk it. I didn’t have a dog but did keep an old iPod and some Band-Aids. The sirens stopped after two minutes like normal, and Bruno announced this was it, the siren tower was kaput, to fuck the radio, that we had to get downstairs ASAP. Bruno had just been in prison in Hawaii and hadn’t been to my house, at least not this one in LA, where no one has basements. A can of corn fell from the top of his stack, and we let it roll. I tried to get Bruno to calm down, but he started with, “Here, boy. Here, boy,” whistling, then switched to, “Here, girl. Come on, girl. Hey, girl,” trying to get the imaginary dog to follow him down a staircase that didn’t exist. I told him I didn’t have a dog, and he said the cat was probably already downstairs, that they’re smart, unlike dogs, and know all the best hiding places. I told him I didn’t have pets, and for the first time, Bruno stopped, or at least slowed down, and said, “Really, Henry?” like I was too sad and pathetic to take care of something, to love something, which may have been true. I asked Bruno what would happen, in prison, if the sirens went off, implying that he’d be in his cell, unable to go to a basement, go anywhere. Bruno looked mad, or maybe hurt, that I brought up prison, but pointed out that Hawaiians called air raid sirens hurricane sirens because they were much more likely to be hit by a hurricane. I thought it was obvious to mention Pearl Harbor but didn’t because that wasn’t the point. Bruno continued, “Since we’re on it, I might as well tell you what I did,” even though just that morning, he’d requested that I never, ever ask him what he did. “Last year, I stole a shit ton of …,” but Bruno was interrupted by an explosion, a massive thundering boom, followed by another and another and another, growing louder and louder and louder, closer and closer and closer. I peeked out the window and could see black smoke billowing, fire in the sky, planes in the distance, flying our way, little black dashes falling from their bellies, triggering more explosions. I picked up the corn and grabbed my glasses and phone charger. I steered Bruno into my bathroom, setting the food on the toilet tank, inviting him to sit with me in the tub. We perched toe to toe. I wondered what that was like, prison in Hawaii, to be so close to all that beauty, to paradise, but to be kept from it. It was worse, I would guess, than prison anywhere else. “I don’t have a basement,” I told my brother, and again, Bruno looked at me like he’d never seen someone so alone.

by Kenny Tanemura | Feb 2, 2023 | micro

The swaddled newborn startles awake at a quarter to midnight. I plug his mouth with a powder blue pacifier bearing an elephant with a right ear so large it emerges stone soft, shaded blue, white sharply outlined. The eye drawn in a horseshoe shape makes it somehow female, downward-looking as if charmed by the field of starry campion and flat-topped aster tucked away in the semi-shade behind her.

He sleeps, and I wonder why the last thing I notice about him is the ruffled breathing, little breaths trying to mass together but cresting like a stillborn wave in the lake belonging to the port town with streets so small, they look like they should be on the board of a children’s game or in an old cartoon. His breaths build up to nothing more than half sighs, and air snagged in the throat a second—a satin cape torn by a rose’s thorn hidden in the oblique dark.

The sour milk smell of him fades when I untangle my nose from his few tufts of hair as if sprung up between flowers or in the cracks of sidewalks. The arm jerks up half or fully asleep. He wriggles spasmodically as if he’s trying to break out of a shell or shake free of this world.

I almost always forget about how kissing his cheek leaves a soft impression on my lips. His skin, cool and taut, lingers there until I wipe it away with the back of my hand, the hairs sweeping the impression into a bin.

The last thing I always think of is the taste of tiramisu and chamomile and watermelon still in my mouth. An afterthought, as I’ve never known the taste of this world until my son came screaming into it, making the abstractions (no more of this world than rabbits are of hats) fade into the savanna where light spreads across the woodland-grassland as far and wide as it wants.

by Chris Haven | Jan 31, 2023 | micro

This little boy has forgotten how he was made. He is old enough to know he can’t ask his teddy bear, but he is still young enough to love that bear and believe that it can feel the same pain and joy that the boy does. This boy knows he can’t ask his mother because she would lie to him, as she always does. The boy can’t ask his father because he is sure the two of them cannot have been made in the same way, judging by their likes and dislikes, the different ways they smell, and all that coarse hair. He is a smart boy but not trusting, so he relies on his powers of logic. He must have a poor memory because it’s strange to forget something like your origin. He can’t have been built like a chest of drawers, or sewn together like a flag, or forged like a sword. He wonders if he was made of something like ice, so that whatever water he was made of was unrecognizable because of his current state. And maybe that unrecognizable something doesn’t even have to be, say, a bone, or a heart. Maybe that thing can be laughter, or the sound of a wet finger against glass, or a wish. Maybe the one who created him is seated in the cup of the moon, looking down, still wishing. The boy has wondered if maybe he was a mistake, and that’s why he can’t remember, why he’s been left alone with these thoughts. Or maybe those wishes from the moon are nice when they leave but turn to troubling thoughts when they arrive. Maybe that distance causes interference, so the result is like a glitch in a video. He picks up the glass of water beside his bed, dips his finger in. He rubs it against the rim of the glass until there’s a whine, and another. He wonders how long it will take the little boys he’s making to find him and what will happen when they meet. When the time comes, he knows they will have a lot of questions. He wonders if he will tell them how much glass we must all be made of.

Recent Comments