by Christine H. Chen | Sep 5, 2023 | flash fiction

When I go in, the sink is bursting with unwashed dishes coated with moldy leftover scraps, half-filled glasses, cups that balance precariously on the counter rim, ripped open TV dinner boxes thrown on top; there isn’t room for me to set aside the cleaned dishes. The washing skills I’ve practiced back home come to good use.

“It’s real simple,” Lisa said, on my first day. “Just Windex the windows, Lysol the kitchen floor, Clorox the towels, you know, and then, Mr. Clean the toilet bowls, there’s also upstairs…”

This is not the country of brooms and pans, coconut brushes, or Pledge oil my mother used to shine our armoires. This is new territory. I’m learning that Americans can make verbs out of proper names. There are specific products with different colors for a given task.

Upstairs is a big room filled with a jumble of chairs and stools, various artwork framed in all shapes and sizes, boxes of clocks, oversized clothing, a jagged landscape of abandoned animals. I wipe bodies of deserted things with a cloth, rinse it with warm water, repeat. In the end, they still look the same. Forlorn and unclean.

Downstairs, Lisa pulls out a blue ice pop from the freezer while I have my arms soaked in a bubble bath of Palmolive detergent. I’m scrubbing a week-old worth of stuck grilled onions on dinner plates.

“Want one?” she says.

I shake my head with a smile, resist the temptation to ask why it’s blue, if it tastes like Windex in her throat, what she’d call that shade of blue.

“Where’re you from again?” she asks.

At this point in my life, I’m reluctant to speak English because I know I have a weird accent. When I tell her where I am from, her eyes grow big. I can see her mind goes in loops. “Oh, is that in Malaysia or Australia?”

I hate to disappoint her. She’s a nice lady in her thirties, long blond hair, freckles on her cheek that remind me of a cheetah. There’s a boyfriend with Oreo crumbs stuck on his T-shirt that lurks around sometimes. She doesn’t make me vacuum her bedroom. I’ve never seen her bedroom. She pays me $20 every Friday, enough to buy a nice stack of letter paper decorated with music notes and red violets to write to my parents back in Madagascar, a T-shirt with the Golden Gate Bridge, and I still have extra dollar bills saved in a Danish cookie tin.

I explain that it’s a big island in the Indian Ocean. She says, “Oh right!” like she got it. I know. I’m confusing. I’m a dark Asian girl who speaks with a melange of accents Americans can’t put their finger on.

She sits back on her couch, licking her frozen blue ice, her eyes fixated on the screen where there’s a couple who’s yelling profanities at each other. Fuck you, go fuck yourself, piece of shit, cunt. I love saying American curse words when I’m alone in my dorm room. They don’t mean anything to me, but they are sharp, decisive bursts of sounds I imagine screaming from the open top of a Chevy on a deserted road, hair whipping air, like in the movies.

by Whitney Collins | Aug 31, 2023 | flash fiction

Marvin’s tumor is the size of an unshelled walnut. His doctor, who wears bile-colored Crocs, has told Marvin and Marvin’s wife, Cathy, that he plans on removing the tumor with a knife that’s not really a knife but a beam of light. When the surgery was first explained, Marvin saw a hot spatula cutting cold cheesecake, but now that the operation is tomorrow, he keeps seeing a red, plastic flashlight pointed at a dense, winter wood. Who goes there? He hears the surgeon call out, gleefully. Make yourself known!

The neurosurgeon is as young as Marvin’s son, Brian. Brian no longer speaks to Marvin. Brian lives in Arizona with a girl Marvin and Cathy have never met but whose name is Begonia. They’ve seen a picture of their son and this girl. A dog that looked like a coyote was also in the picture. “Who wants a cartoon for a dog?” Marvin asked Cathy. “Who wants a houseplant for a girlfriend?”

Marvin was a terrible father, but the tumor has lessened the reality of this. The larger the tumor grows, the better the father Marvin was. And the faster Marvin walks, the faster the tumor grows. Which is why, every morning, he goes to the mall in his big white shoes, the ones that look like loaves of junk bread, and walks eight-thousand steps. He walks the length of Pinesap Plaza fourteen times, back and forth, and as he does, he recalls things he thought about doing with Brian as things he actually did. Camping under a swirl of stars. Shooting clay pigeons. Making cowboy beans in a cast-iron frying pan. “There’s Orion,” he hears himself say. “More pintos?”

In the early morning mall, the managers raise the gated storefronts with much audible ado. The mall fountains sputter to life. Together, the fountains and the gates sound like static, and Marvin’s mind becomes the roaring space between canyon walls. He passes stores. There’s Queen B., Banana Pants, Mr. Stupid. He stares at the things for sale and cannot remember what they are for. He imagines a pair of underwear on a potted begonia. A woman’s yellow sweater on a coyote. A whoopee cushion as a map of Arizona. Marvin moves his big white shoes faster. He forgets Brian’s thin shoulders and crystalline singing voice. He forgets Brian’s pitiful deer eyes, his milkweed hair. Instead, Marvin remembers throwing a football that was never thrown, laughing at a joke that was never cracked.

At the end of Marvin’s morning walk is Sprinkles, the ice cream kiosk. If Marvin times it right, he takes his last step when Dashel, the ice cream boy, flips over the OPEN sign. “Good morning, Marvin,” Dashel says. “The usual?” Marvin’s excitement is such that he can only nod. His head nods and the tumor nods, and fireworks go off in Marvin’s mind— red and green and violet.

Dashel scoops the vanilla while Marvin watches. It’s a sphere of snow rolled through a pristine field, the belly of a snowman that Marvin and Brian did and didn’t build. Dashel rolls the vanilla through rainbow sprinkles, a brain dragged through artificial memories. He puts the ice cream into a paper bowl and places a shelled walnut on top. He hands the ice cream to Marvin, and Marvin goes and sits on a bench by the fountains. Every morning, he sits there until the ice cream has melted and the sprinkles have bled, and all that remains is the walnut—floating in gray matter. Tomorrow, Marvin will have his brain, but today he has Brian.

by Hillary Ann Colton | Aug 28, 2023 | flash fiction

The shades are pulled down by Mick before the summer sunsets. Mick is a regular: he spends every day, open to close, in the bar drinking Bacardi and Cokes and shots of Fireball. He buys drinks for everyone and tells them he loves them. He loves me the most; he’s proposed seven times.

His facial veins match his red hair, and his arms are speckled in bruises that are as dark as frostbite. He’s in his early sixties with an adopted teen at home. He tells people his wife died from a flu vaccination, but he told me once that her body couldn’t take anymore, and he doesn’t talk about her until closing time.

Mick throws a fifty down and says he’s gonna pick up a pizza on the way home. “Coming back?” I say.

“You know it,” he says.

And I do.

Buffy refuses to sit on the left side of the bar because she has Mac D. She’s been divorced five times and loves to talk about her sex life. Most people sitting at the bar top have seen at least one of her nipples. Buffy drinks vodka sodas in a pounder and needs a napkin to wipe the lime off her hands after squeezing.

She tries to hook her straw with her fat tongue and asks about me. I’ve learned my lesson with this question: no one actually wants to know.

“Great,” I say, smiling and hopping a little. I feel happy after taking a shot in the back. “I have a date for WNGD.” Buffy grabs her phone and shows me a picture. She’s already told me this, so I know that WNGD stands for World Naked Gardening Day. She is sixty-two, and not only does she have a better sex life than I do, she is confident enough to pull weeds naked while a man she met online watches.

A woman I’ve only just begun to recognize scoots down to sit by Buffy. She tells us about her tomato plants: where to get them and how to nurture growth. We don’t care, but we pretend to.

When my patrons ask me how I am, I say I’m good, busy, but good. I could say that my life is messy, and I move from toxic to toxic, and I spend my time watching Kim K tutorials on how to contour my face in hopes that I’ll make more money if I am no longer myself. I’m good; I’m busy gets me a nod and smile as if my Daddy were calling me a good girl after I fetch him another beer.

Mick’s back, and he says all his kid wants to do is play video games. I could say that it’s his fault because he’s never there, he’s here, but instead, I get us shots. “Damn kids these days,” he says.

I pour beers for the men and vodka for the women and shake sugary liquor for the newly-legal. I allow myself a shot for every hour that passes because I tell myself I can’t handle the drunks when sober.

Mick sits by Buffy and makes jokes about her wet wet pussy, and she laughs like she genuinely means it. People play pool together and request that I turn the volume up on the jukebox when their song comes on. Unfamiliar faces come and go and play pool and throw darts and dance and laugh and touch.

A keg blows, and the tap sprays my face with white foam, making my mascara look wet. “I bet that’s not the first time someone’s blown in your face!” Clint says. A patron who wears four-hundred dollar cowboy boots and blazers and sells things on the radio. When I swivel the new keg to its place, my boobs nearly fall out and catcalls follow. I laugh like Oh well! and give them a little shake as I readjust.

My oldest patron is named Dick, and he used to direct plays on Broadway. Without fail, he tips two bucks. He offers me fifty to take him out back and show him the girls. “Maybe for your birthday, Dicky,” I wink. He’ll be eighty-two in January, and I hope he’ll die by then so I won’t have to.

The bar-back shows up, and we take a shot together. He hugs me, and the women tell us how cute we are, and the men pretend not to be jealous. We take a shot, and I know he’s in love with me, but I have a boyfriend that no one knows about because he isn’t allowed in the bar. Boyfriends are unpredictable, and mine’s a Gemini: moody like fire. According to the Zodiac Gods we are destined for each other. I don’t feel it when he’s cold, like winter mornings, but when he’s warm, I am a fucking Queen. I am everything.

A month later, the tomato lady disappears, and it’s because she died of liver failure. Everyone at the bar will take a shot and cheer: “To the nice tomato lady!”

In the new year, Lo, the pizza guy who drank Coors Light, will overdose. I just saw him the other night. He was sitting right there,” we all say.

Jenn will crash her Honda into a nail salon. She was trying to quit, but the tremors––she lost control.

Mick’s doctor will tell him to quit drinking, and for two days, he’ll switch to beer. A young drunk woman is scared of a man who got her a cab, so I sit her down and say: Don’t move. When I look up again, she’ll be gone.

Steve will get a DUI, and we’ll all forget about him.

An employee and friend will die of a seizure after two months of sobriety. We really loved her. We’ll attend her funeral and drink to her favorite shot: Tuaca and Red Bull. We’ll look at pictures of her when she was in her twenties, and we won’t recognize her because she wasn’t pickled.

We cry at our losses and devour our poison and tell ourselves that only the good die young, so full of life, and we swear we won’t be like them.

We won’t.

by Elizabeth Conway | Aug 24, 2023 | flash fiction

Kerry found a hundred-dollar bill at the gas station near pump three. It was covered in oil. She carried the money inside to show the attendant, Jeremiah. “A hundred bucks! What are the chances?” Kerry said. “Lucky,” he said. She bought two cans of Dr. Pepper, and Jeremiah counted out her change. She slid him back a five. “Lucky,” she echoed. When she got home, Kerry called her sister. It was Sunday. Kerry always calls her sister on Sundays. 6:45 PM sharp. She told her about the hundred. The sisters agreed Kerry should buy a bus ticket and come down for a visit. Greyhound was offering a $55 roundtrip to Florida at the end of January; she would even have some mad money left over to burn. Lucky.

Kerry believes in luck. Believes in routines. She performs even the most mundane – like brushing her teeth two minutes on the top with her right hand and two minutes on the bottom using her left – in predictable patterns. Kerry doesn’t believe everything she does brings good fortune, but she’s unsure exactly which routines, which actions, control her fate, so she stays committed to them all. Like the Sunday phone calls and now the Dr. Peppers. She buys them again and again, carrying them home in the pockets of her brown jacket. The cuffs frayed; its last three buttons lost long ago. Kerry dares not throw it out: a good-luck uniform.

Kerry packs her clothes in layers shirt, shorts, shirt, shorts, then adds a heavy windbreaker — Florida can be unpredictable. On top of her clothes, she puts a framed photograph of herself and her sister at the Minnesota State Fair. In the picture, her sister is a toddler, and Kerry — six years older — holds her sister propped securely on her hip. They are standing next to a brown calf. Like the sisters, the cow looks directly into the camera. That was the year the tornado hit Fridley. It took out their barn, twenty-two of their cattle, thirteen people. Kerry and her sister hid in the laundry room, under the sink. The sky was yellow and green. Their mother kept the front door open, “I want to hear what it sounds like,” she said. She could hear a train. There wasn’t a train. The state fair calf survived. They sold it to a farmer from North Dakota, and for the rest of the summer, Kerry slept in the laundry room. Her mother didn’t argue. The summer storms waned. Later – later – when the summer passed, when the storms moved on, Kerry moved back into her bedroom, and her sister’s appendix burst. In the room they shared, Kerry listened to her sister cry in pain and pulled her pillow over her head to muffle the moans that kept her awake. In the morning, their mom wiped vomit from her sister’s mouth before placing her in the truck to drive to the hospital. She stayed for a week. At home, Kerry stripped her sister’s bed and washed — and re-washed and folded and re-folded — the twin-sized sheets with a faded strawberry print. Kerry moved back into the laundry room and whispered and whispered — I’m back I’m back do you hear me, hear me — until her throat was raw to whoever, whomever was listening.

At the station, Kerry’s bus is late. Over an hour — delayed by the January snow. Kerry chews on her bottom lip. She checks her watch: 8:13, 8:13, 8:14… At 8:30, she stands up, puts her hands in her pockets, and pulls out a pack of Life Savers. She rolls the candy between her fingers until her knuckles ache. Then, he switches hands and does it again. Kerry has never been to Florida. Never. “This is a mistake,” she says. Kerry grabs her suitcase and starts to walk out of the station as the bus pulls into her pathway. “This is a mistake,” she says when boarding. Her seat is next to the window. She shares her row with a man from St. Cloud who once played hockey for the University’s Huskies but lost his scholarship when his grades went to shit. “My grades went to shit,” he says. “When mom, got sick, who could care.” And then at the very first stop in Mora, Minnesota – population 2,436 — the televisions, cornered in the corners of the station where people ushered through for bathroom breaks, bitter coffee and easy food, suddenly synced with news outlets across the globe to broadcast the same, the same, the same. This just in. This is a mistake.

So when they watched the spaceship explode, when it burst in the Florida sky, disintegrated over the Atlantic Ocean while crowds gathered for the countdown, while news stations went live, while children and their teachers watched in auditoriums across the country to celebrate one of their own who boarded the ship with an apple for luck — seventy-three seconds, then gasses, then fire so explosive, so hot it turned metal, turns bodies, into dust that disappeared into the atmosphere — Kerry stood up and screamed, “I’m sorry! I’m sorry! Forgive me!”

Eventually, she would get home – as would we all – and unpack our shirts as quickly as we could: shirt, shorts, shirt, shorts. Brushing the sugary candy out of our teeth, the University hockey player off the roster — top right, bottom left. Wash, rinse, repeat as the instructions instruct. The recipe, the rules. Wash, rinse, repeat – prescribed prescription. I’m back I’m back! But by then, it didn’t matter. It is already too late.

And so it goes. The gas station, the cans of Dr. Peppers, the brown jacket with frayed cuffs, hockey players from the north en route to the south, the calls to sisters in Florida. “When are you coming?” she asks. And Kerry responds, “I can’t. I’m sorry. Forgive me.” Now part of the routine, too. And then so it goes. For gracious, merciful, benevolent God in heaven, so it goes.

by D.E. Hardy | Aug 21, 2023 | micro

You could think of it as an evolutionary advancement. Steelheads can spawn multiple times, whereas their salmon kin buck their way upstream only once. It’s a good thing: the average steelhead dad swims out to the big ocean for a couple of months, has a time of it, then comes back to his small hometown river to make a family. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat. Higher chance his DNA survives. Nobody holds it against him. Nobody gets cross. Nobody gets pissed at you for sticking up for him. He’s your dad, and it’s okay to like your dad even though he left. It’s not bad to have multiple families. It’s the whole point.

You could think of it as an act of optimism. A steelhead dad doesn’t need to stick around because he trusts his kids to handle themselves. A small-time river’s not so big that a young fry can’t figure things out. You hatch; you swim. That’s it. Somebody will be around to show you how to catch a baseball or fix the chain on a bike or mow a lawn. That’s what an ecosystem is for.

You could think of it as a simple fact of nature. Steelheads don’t know who their half-siblings are, so you never know when you might swim by each other. It must happen all the time. They might live near you or maybe one river over. They might look exactly like you with the same square jaw, the same hair so blond it’s silver. Somebody might say they saw you at the K-mart off M-39 even though you were at little league. Somebody else might swear they saw you at the Pizza Hut buffet because the kid used cottage cheese as a salad dressing, just like you do. You might go to the county youth fair with your mom and wander toward the carnival games. You might come across a booth with a giant trout marquee where a kid that looks like you stands next to a lady your dad used to work with, playing one of those fishing games where you try to catch wooden fish with a magnet, you grabbing your mom’s wrist, saying, Please don’t, she stopping cold, saying, That son of a bitch.

by Aimee LaBrie | Aug 17, 2023 | flash fiction

It wasn’t a date exactly. He said, “Do you want to see a dead body?”

I said yes.

I would have done anything to spend time with him. I was a secretary for the medical school, and he was a student. He liked to drop by and talk to me between his neurology lecture and gross anatomy.

It could even be that I suggested it. Maybe he was leaning on my desk between classes, talking about anatomy lab. Armen—he had curly dark hair and a prominent Adam’s apple that I wanted to press my mouth against.

Maybe I said I wanted to see it—the body.

He led me to the lower level of the building. I didn’t even know I was working in a place that housed cadavers. He gave me a blue gown to put on. He tied the strings gently in the back, careful not to touch me.

I could feel him behind me, his breath on my neck.

He said, “Are you ready?” I nodded. The room was filled with what looked like silver operating tables. He pressed a button. The table vibrated, made a humming sound. Two slits opened, and the body rose from underneath, covered in a plastic sheet.

The smell of formaldehyde–I knew it from my own high school anatomy class when we dissected alley cats. The pungent, sharp smell ballooned inside of me, and went straight to my temple, with a needle-like pain.

I took two steps backwards. He caught my elbow. “Are you sure you want to see this?”

“I’m fine,” I said.

He pulled back the sheet. A woman, skin ashy gray. What was left of the skin. You couldn’t even really think of her as an intact body. They were in week 12 of dissection.

I stepped back when I saw her face. It was the lady outside of the Broad and Snyder subway stop, her skin tanned from being outside, wriggly hand-drawn tattoos snaking up her arms like bracelets. She always held the free paper, Streetwise.

Every once in a while, I would buy a copy. That meant giving her a dollar and taking the paper down into the subway with me and then leaving it on a bench in case she ventured down there to get it again. Two for the price of one.

On other days (most days), I would cross the street to avoid her, take the subway entrance on the wrong side of the street so I didn’t have to face her, teeth missing, stumps in her head, the un-prettiness of homeless people, the way they are vulnerable to everything.

I never caught her name, but in my head, I thought of her as Madge. Madge had a series of wigs she wore, a wild, burly one like Harpo Marx, and another one with long hair and bangs; disconcerting to see her from behind with the shiny hair falling down her back, and then to have her turn, a face shriveled up like a dried apple. I presumed that she did all kinds of things for money, that the costumes were part of the way she made her living. It reminded me of a jock in high school who I overheard saying that toothless women give the best blowies. Nice and smooth, he said.

“You see this?” Armen said. “We had to peel back three layers of fat to get inside.” He pointed to her lungs. “Dark spots,” he said. “She was a smoker.” He turned to the chest cavity with its row of rib bones cut across the sternum so they could see inside. He picked up the heart, moved it around in his hands. “Do you want to hold it?” His voice joking, even as he held it out to me.

It was much smaller than I expected. It looked like a decaying avocado.

Armen took her hand in his. I thought he was pretending to hold it, like they were on a date, but he turned the wrist to show her tendons through the skin. “See this?” With his gloved hand, he identified a muscle, pointed, then pulled. Her fingers wiggled. “She’s waving to you,” he said.

I took shallow breaths, pretending to be interested in the white tangle of her intestines. “Do you know her name?”

He explained that most of the donors were either the homeless or the unidentified.

I nodded my head. It felt strange on my neck, loose, like it could fall off any second and roll across the floor. The woman had probably gotten money for donating her body, money she spent on food or clothes or wigs.

“We’re doing the brain next.” He brought me to the front of the body. This seemed better, away from the carnage of the cut skin, the places on her arms where they practiced giving stitches, the split in her abdomen where they sawed away to learn about her uterus. Her eyes were shut, her face untouched. Long black eyelashes, thin lips, a broad nose. She had dots in her ears where her earrings had been removed. “Look at this,” Armen said. He pulled at the top of her head, and her skull opened up, like a jar.

I stayed where I was. I did not want to see the gray curves of her brain. “What happens after?” I asked.

“After?” he replaced the piece of her skull, smoothed her hair back into place.

“When you’re done.”

He bent close to her body, fingers tapping against her rib cage. He had more he wanted to show me, but there was a ringing in my ears now. It occurred to me that he didn’t have the same feelings that I did. She was just part of his lesson.

“I’m not sure what happens to her after.” He looked at me and smiled. “We haven’t gotten to that part yet.”

by Tonee Moll | Aug 14, 2023 | flash fiction

We want your very best work! Writers at every stage of their career are encouraged to submit, but we want writing that goes hard. We want the stuff that punches us right in the ear, perforating the drum in such a way it prevents us from swimming that whole haunted summer, despite the heat, despite the ghost of missing out.

We want work of any genre that reminds us of the way it felt when we first fell in love with literature, that sensation we got when we first realized that this feeling we had for Zak wasn’t just admiration or jealousy, but that teenage cocktail of lust and hope that bodies can be bound together into something sweet, something sweat, something important and worth remembering. But his grandfather had just passed earlier that June, and we could tell it hit Zak hard the morning that we showed up on his doorstep. We were still on antibiotic eardrops and under orders to avoid blowing our nose, and he answered with an open, loose Hawaiian shirt, and the singe across the crest of our cheeks explained that desire had found its way back into our body for the first time in weeks, but after that initial flush, we noticed there was something off about him, that he wasn’t the charismatic skate kid we’d watched practice kickflips for months, as we sat on the curb with our own deck rolling back and forth beneath our feet. With the late morning sun bending through the glass outer door and onto his bare chest, we realized that he looked hollow—no, not exactly hollow, but, like, separate? A step removed from the moment? Not the person we saw, but like someone behind a windshield, operating his body.

Prose writers, send us 500-4,500 words of absolute heat, keeping in mind that the symbolic connection between “heat” and foundational summer crushes is too obvious, so you’ll need to talk your way into some other sort of figurative framework. Like, do you remember Deana Carter? We think of that song when we think of that summer. And, listen, we know country music is outside of the aesthetic of—whatever this is, but hear us out: yes, “Strawberry Wine” does dip its feet into the cliches of summer and heat imagery, but Carter does it in a way that gives it a little—ya’ know, like—a little turn, a little zing. When she considers the ephemeral nature of the summertime, what is named is September’s arrival rather than summer’s passing. This is season as a sort of haunting. As for “heat,” here too, Carter subverts expectations. One might expect it to arrive in the sun, summer, or bodies, but she offers instead the “hot July moon” as the only witness to her clandestine summer passion, and even though we had started listening to pop punk that year, the country song was buzzing from an alarm-clock radio flipped on for white noise to mask hard breathing. Slipping under the covers alone, the thought of sunlight on Zak’s chest rushing forward, we gently ground ourself against a pillow until nearly breathless, until having the dangerous idea to call him from the phone; it took months to convince our parents to install in the room, then hanging up the moment that he answered.

For poets, send us up to five pages of poetry in any style: we don’t care if it’s free verse, fixed verse, or even experimental—as long as it BLEEDS. We want to feel it, like a sunburn. Like a knee scoured on blacktop in the summer, a Nevada summer, a couple of weeks after we’d seen Zak at his front door. We had been coming to that parking lot of the “other mall,” where everyone skated after school and before work, each of us picking up or setting down fountain lemonades that the Greek pizza joint on the corner would usually let us steal, despite our obviousness, when we asked for free water cups. We want poetry that BLOOMS, the way we did at first, when we saw him squatting outside the driver’s door of a faded Civic, our feelings rising as we recognized his profile there in the afternoon light and unfolding as we wondered why he was crouching like that, and whose car it was, and pausing briefly to chuckle at the thought that it must have been because he was hiding a beer, maybe smoking up.

We want poems that shift our tenses. We want poems that burst into full color when we see Zak slip his thumb deep into the mouth—no, down the throat—of that rawboned emo guy who works at Spencer’s in the “good mall,” and Zak is looking at him, and he’s looking at the ceiling of his car, and that’s when we put together that Zak’s hands must be in his lap, and we can tell that they are moving fast, and Zak’s doing this thing where he’s trying to be attentive to the guy he’s getting off, but he’s also glancing around, making sure they don’t get caught, so at first we don’t think he sees us here, watching them. Then he turns his head and looks us right in the eye, as though he sensed us there, and for a breath’s length, his face shows panic as he realizes someone is watching him, until he registers that it’s us, and, as if we were in on it all, smiles: a disorderly, charming smirk.

We smile back, eventually and also briefly, because we don’t know what else to do, then look down, pick up our lemonade cup off of the curb, and kick our deck forward to ride the opposite direction, away from asphalt lot.

For some reason we still can’t pinpoint, the most vivid memory left today isn’t the smile, but the paired rasp of wheels on concrete, the rhythmic click as we slid along the sidewalk, away from longing.

No simultaneous submissions.

by Fractured Lit | Aug 11, 2023 | interview

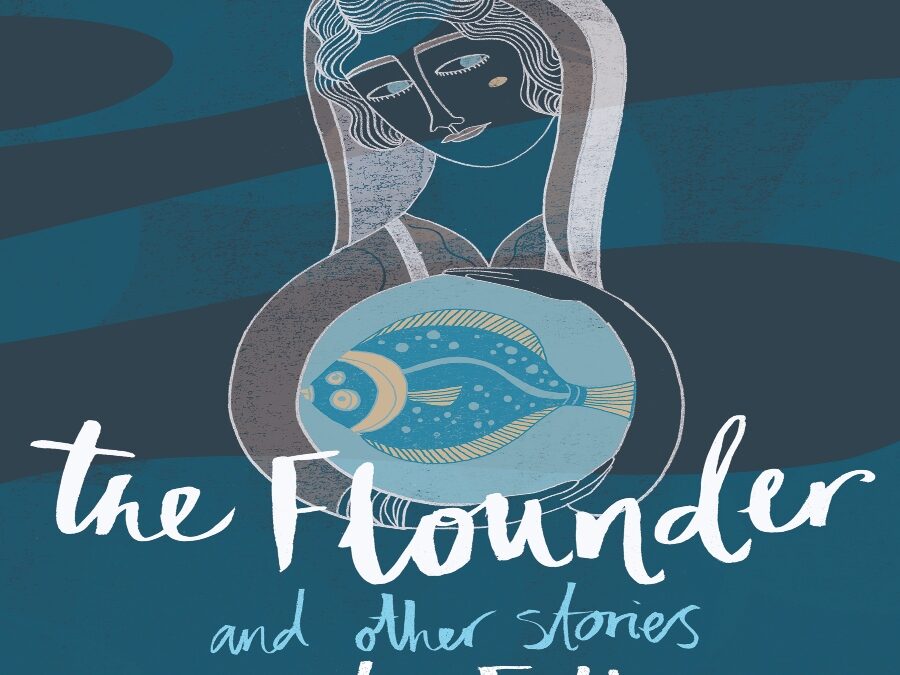

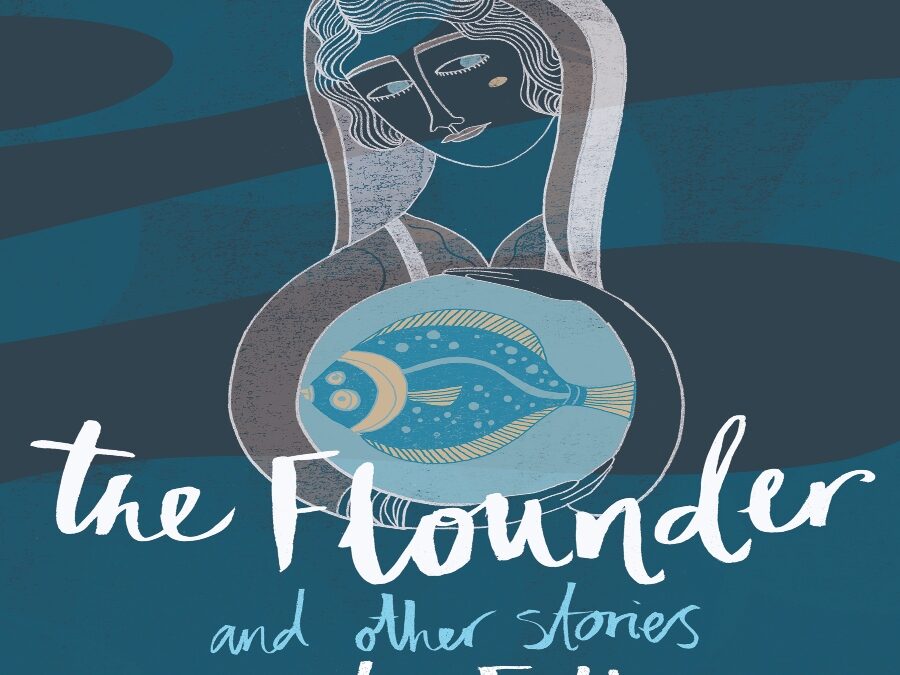

I think I found John Fulton’s short story collections somewhere in my early writing days; after reading stories by Carver, Baxter, Bausch, Jean Thompson, and Tobias Wolff. I’ve always found a warmth and a beating heart in John’s stories, a way of seeing the world in both the light and the dark, with a punch of language and a care for his characters that might have been missing in those earlier stories that made me want to be a writer. In The Flounder, Fulton has found a deeper reservoir, a confidence in his characters to reveal themselves, a confidence in his sentences and structures to affect the reader, to make a fountain of resonance I plan on returning to soon.

Tommy Dean: So many of these stories have great opening lines full of conflict and intrigue. Do you have the first line when you start a story, or do you create them during the revision process? Do you consciously try to load your stories with conflict in the openings?

John Fulton: Great question and observation! The opening lines are extremely important to me for two reasons. First, they help give clarity and direction in the vast forest of ideas, characters, and images that tend to arrive indeterminately at the beginning of the writing process. The first lines provide a trail of breadcrumbs, so to speak, that I can look back on for an idea of where the story might go next. Before I get that crucial first paragraph, I’m often lost. But the opening may not come until I’ve made a mess, written many aimless paragraphs or pages and wandered through the accumulating material. But in the wanderings, I can stumble upon a sentence or two that begins to suggest the stakes and focus of the story or, simply, what it’s about.

That’s where “conflict and intrigue” can be crucial because they tell me both what the story is about and why it matters. The beginning of the third story in the collection, “Box of Watches,” is one example of how important a clear statement of conflict and stakes are when I begin:

That Friday afternoon in AAA Guns and Jewels, Shaun’s life flashed before his eyes, just as they said it would when you faced death, though it wasn’t his death but his grandfather’s that made the events of Shaun’s 22 years begin to reoccur as soon as he heard the old man shout, “Go right ahead and shoot me, you little shit!”

As soon as I arrived at these lines about a grandfather and his grandson, Shaun, I knew a great deal about the story that would help me write it. Of course, this is a hold-up story, and I knew that there would be a gun in it and where the action would take place (in a pawnshop), before I arrived at these lines. But that phrase about “Shaun’s 22 years” suggested that this character’s entire life with his grandfather would be in play, that a kind of chronicle of that life would unfold during the robbery, and that one of the challenges for me as a writer would be the tightrope act of balancing present action (the hold-up in the pawnshop) with past action (the scope of Shaun’s life with his grandfather up to this moment).

Secondly, the initial lines of a story are crucial to me because they make an assertion about how language will work (diction, syntax, sentence length, the quality and tone of images, etc.) in the story. This is not about content or event or stakes so much as it is about sound, rhythm, and cadence. For example, the cadence and pace of that first sentence above suggest the menace of the gun before we see it. The first sentence is long, full of momentum and kinetic energy as are most of the sentences that follow. There’s violence in the language, and that works in tandem with the story. I often tell my students to “follow the language to the story,” by which I mean to be sensitive to the sound the words make and allow them to lead you organically to what comes next.

TD: Most of your stories eschew the use of quotation marks. Did you have a purpose for leaving them out? What does it add or take away from the reading experience?

JF: I often don’t find quotation marks necessary because good dialogue sets itself off as speech immediately. Its rhythms, tone, and diction distinguish it from the rest of the language of the story. I think fewer symbols or marks on the page can make for a less mediated reading experience. Signs and guideposts that tell you how to read necessarily take up some mental space. Without those little curled lines, you can simply read and hear the speech rather than have it dictated to you as such. Of course, the writer has to get the dialogue right. If there’s real confusion about whether a line is dialogue or not, that is likely the writer’s fault.

TD: Your stories are often populated by characters who refuse the conventional for their lives. Are stories made interesting by or through characters that refuse to follow the “rules” of society?

JF: Thanks for that observation about my work, Tommy. I wouldn’t have said this about these stories. But now that you bring it up, I see that you’re right. My characters do cross lines, though many of them live inside communities that have rigid lines, which makes the crossing of them impossible and/or irresistible.

This may have something to do with the fact that I was brought up by a single mom in the 70s and 80s as a fundamentalist Christian. There’s not a lot of wiggle room in this community, and those in it are often motivated (and manipulated) by powerful emotions—shame, guilt, fear—to stay on the straight and narrow. My family lived in the rural Western U.S. (Montana, Utah, desolate parts of California), where this religion and others like it (mostly Mormonism) were very common. I don’t recall meeting an atheist, or anyone who would call themselves “secular,” until I was a teenager and living in a real city (Salt Lake City). I eventually escaped that world, but it took a few decades and some years living at a great distance from home. I spent about five years in Europe in my early and mid-twenties.

In The Flounder, I write about this experience (both living inside rigid faith communities and escaping them) more than in any of my previous books. Until recently, I found it hard to represent this world. I tend to need decades of perspective on autobiographical material before it works its way into my fiction.

Characters who break the rules are interesting because we can’t pin them in or anticipate their next move. The first story in my collection, “Saved,” begins by highlighting just such a character: “It was true what Mrs. Berry said: No one expected to see an old woman in a muscle car, a convertible Mustang with polished chrome bumpers, a hood scoop, and an engine that ran with a throaty hum that we could feel in that soft place just below our stomachs as she pulled alongside us one day on our walk home from school.” The opening announces that this old woman isn’t who the two pre-adolescent kids at the center of the story expect her to be. She loves fast cars and challenges the fundamentalist views of these two kids, who live in fear of being left behind when the Rapture takes place. While Mrs. Berry and the kids befriend each other, the challenge she poses to their beliefs eventually causes havoc. Faith is powerful and losing it is painful. But the old woman also frees them—or begins to free them—from some very constricting ways of seeing the world and themselves.

TD: I loved your use of the second-person point of view in your story “Stitches.” I wonder if this point of view is best at exploring certain power dynamics between the main character and the antagonist? I expected the main character to be a younger boy, so I’m wondering if you were playing against my expectations? Why don’t we see this point of view used as much with older narrators?

JF: The second-person point of view is mysterious. I don’t entirely understand why it works in certain stories and, at least for me, doesn’t work in others. At its core is a contradiction or dissonance, especially when the “you” is an individuated character. In “Stitches,” the second person pulls the reader in with a seemingly generic address (the “you” could be the reader or a kind of “every person”) even as we learn that the “you” in this story is a middle-aged professor of English on a hunting trip with his elderly and somewhat estranged father.

This inherent dissonance or intimate distance in the “you” was instrumental for me when writing the story because it’s probably the most autobiographical piece of fiction I’ve written. Like the “you,” I am a middle-aged English professor. I have two kids. I didn’t know my father very well when I was a youngster and now see him a few times a year on hunting trips when we talk about a limited number of subjects: football, construction projects, the weather, and, more rarely, why he chose to leave our family before I was old enough to remember him. (Note that a lot of other things in the story are made up.) That’s charged material, and the second person point of view created, I think, a lens through which I could look at and inhabit these characters both from the inside and from an almost clinical remove so that the sentiment in the story would be at once felt and carefully observed. It’s not, I hope, merely personal. By the way, this wasn’t an intellectual decision I made while writing the story. I tried the second person and it worked or, at least, allowed me to enter and engage with the material in a way that first or third person didn’t.

Your observation—that the second person is often used for younger characters and not older—is interesting. I think you’re right, though I’m not sure why that is. There are a lot of coming-of-age stories that utilize it: Junot Diaz’s “How to Date a Browngirl, Blackgirl, Whitegirl, or Halfie,” Loorie Moore’s “How to Become a Writer,” and Peter Ho Davies’ “How to Be an Expatriate.” Perhaps this is because all these younger narrators are experiencing the disorientation of becoming an adult and colliding with the structures in society (sexism, racism, nationalism) that don’t recognize individuals. The dissonance in the “you” captures the confusion of that—of being or becoming one thing while being seen as another. These are also all how-to stories, which has become a genre of the second-person story since the you is a stand-in for an assumed audience that wants to learn something. “Stitches” doesn’t belong to this genre. Instead, it’s a story about family trauma and it may have, at least in part, been suggested by a second-person novel that is also, at its core, about trauma: THE DIVER’S CLOTHES LIE EMPTY by Vendela Vida. I’d highly recommend this book. For obvious reasons, the second person, with its tension between distance and intimacy, can be expressive of trauma.

TD: One of my favorite stories in the collection is “What Kent Boyd Had.” How did you discover/find this character on the page? Did the point of view come to you in the very beginning? It has a masterful use of omniscient narration, but I never felt too far away from this main character! How do you often go about creating your characters on the page?

JF: I’m glad you liked that story. It was a lot of fun to write. It’s what I call a “list story,” which is what it sounds like: a story told in the form of a list of things that the rapacious and loud Kent Boyd accumulates over a lifetime. The story came from years of teaching and thinking about Tim O’Brien’s classic short story “The Things They Carried,” also a list story that brilliantly gives expression to the experience and trauma of the Vietnam War for a platoon of soldiers. O’Brien uses long lists of the sort of equipment these soldiers carry through the jungle. With these lists, he characterizes them, creates tension, and structures the story. Using this form to tell a good story is tricky because lists aren’t inherently dramatic. They’re simple storage devices for data that help us remember what to get at the supermarket or for Christmas gifts, etc. The challenge, then, is how to create tension and human drama with this simple form, which I could talk about all day.

But the more important question is, why use a list at all. For this story, it had to do with the character of Kent Boyd, who is “self-made” and the kind of man who is out of fashion these days. He’s a close cousin to John Updike’s Harry (Rabbit) Angstrom in the Rabbit novels and perhaps Philip Roth’s Nathan Zuckerman. He’s also an amalgam of a few of my uncles. These guys aren’t necessarily pleasant, though they know how to have a good time. They have outdated ideas about their own privilege, not much self-knowledge, and tend to see the world as a place that belongs to them. Their egos are large in inverse proportion to their vulnerabilities and deep-seated and often unacknowledged needs. The list becomes important and expressive of Kent Boyd because he grew up with little save for his backwards Christian faith, which he loses as a teenager. He goes from Pueblo, Colorado (if you’ve ever been there, you know it’s not a place you’d want to stay) to Berkley and finally to Boston, where he becomes a successful and wealthy patent attorney. Given his childhood, it’s not surprising that he sees life as a process of acquisition and starts accumulating people, accomplishments, and things: a wife, kids, a few big houses, fancy cars. But the story undermines him by including things that don’t fit with his ideas of success such as alcoholism, affairs that end badly, erectile disfunction, heart disease, a bottomless need for approval and love, a terrible fear of death, an angry adult son, etc. These are the items that express complications and contradictions that are necessarily human and that, I hope, create the tension that fuels the story and that gives this character depth and interest.

TD: What does your perfect writing day look like? How often does this happen?

JF: My ideal writing day would be 4-8 hours at the desk, with no distractions or other obligations, when I’m absolutely in the zone and focused on a project in progress that has me so excited and expectant that I can think of nothing else but what’s happening on the page. I have two kids, which means there are usually other obligations, places to be or go. I’m also a professor and I direct the MFA Program at the University of Massachusetts Boston. I really enjoy my students, my colleagues, and the program. But all this requires attention and time, which often means no writing on some days and no more than a couple of hours on other days. Being in the zone feels mostly like luck. However, it has very little to do with luck. I usually get there only by being lost and frustrated for many hours and days and sometimes months at a time. I need to produce material—pages and pages—to find the story.

As for the second part of your question, I’d say that I experience no more than a month (sometimes two) every year of ideal writing time. Typically, this would be in the summer when I’m not teaching. That said, I try to make it to the desk at least five days a week, and I’ve gotten a lot of work done on less-than-ideal days. Alas, that’s life: almost always less than ideal.

TD: As a writer of several short story collections, how do you find the unexpected in your new stories? How do you keep yourself from repeating plots or themes?

JF: I love this question in part because I don’t entirely know the answer. I can tell you, however, that once I start to repeat myself, the work suffers and feels stale, old, enervated, all signs that I’m too much in control and know too much about what’s going to happen on the page before it happens. If my work isn’t surprising and unpredictable to me, it won’t be those things for my reader.

That said, I think writers tend to find material in what obsesses and bothers them. And writers gravitate around the same issues until they’ve exhausted them. Obsessions are good and I follow them. To be more specific, an obsession can be ideas or clusters of images or situations or an experience that shadows me like a dream I’ve just woken from and can’t quite articulate or fully describe. It often takes years for me to find the form or language that will allow an obsession to become a story. Messing around, improvising and experimentation can do the trick. For example, trying the second person point of view gave rise to “Stitches,” while using the form of the list made “What Kent Boyd Had” possible. I’d been trying to write the title story of my new collection for decades, but I wasn’t able to finish a draft until I structured this tale of infidelity around a Grimms’ fairy tale, typically called “The Fisherman and His Wife,” though it’s also sometimes called “The Flounder.” Once I’d introduced the strange magic of this fable into the texture and language of the story, I was able to write it.

I think a large part of keeping the work fresh and new involves following our instincts. While part of writing is about discipline, craft, keeping the language sharp, much of it is about dreaming, following hunches, not overthinking the next step. Finally, of course, we have to be out in the world, live, take chances in our lives, and broaden our experience.

TD: How has publishing changed from the beginning of your career to this book? Any advice to writers of story collections?

JF: I’m not an expert on publishing, but the big houses have undergone more consolidation and corporatization, which means more pressure for profits. The bestseller has become, I think, the focus, whereas a decade or two ago, a number of books that sold modestly could serve a publisher well. Midlist authors—those who aren’t bestsellers—generally have a harder time right now. My first two books, a story collection and a novel, were taken by Picador. But when my agent submitted my third book, another story collection, Picador wasn’t interested. They wanted a novel or nothing.

The good news is that there are more independent and university presses than ever. It’s still tough for story collections and a lot of these presses don’t make it. The wonderful imprint (Yellow Shoe Fiction at LSU Press) that published my second collection of stories went under when Covid led to budget cuts at LSU. I just wrote a piece on the form of the novella, which will appear this month on LIT HUB. I love long stories. Many of the entries in THE FLOUNDER come to about 10,000 words. I’ve published four novellas, which I define as stories of about 15,000-50,000 words. For the piece in LIT HUB, I read a pile of wonderful novellas, an experience that gave me faith in the culture of literary publishing in this country. The novella has mostly been ignored by big houses, with some exceptions. But independent presses (Black Sparrow Press, Akashic Books, Dorothy, Seven Stories Press, and many more) have championed the form. You’ll have to search for them, but the novella is alive and well.

As for my advice to fellow writers of story collections: Make sure your work is the best that it can be. Then persist in looking for a press that believes in the book.

TD: Do you have an interior monologue? How does this inform your writing?

JF: I have “interior monologues” and some of them aren’t great. At times, I find myself reading popular books with an envious eye. That’s unhealthy. My constructive interior monologue is simple: Follow your gut. Read good stuff from a range of literary traditions and with an eye towards the limitless possibilities of language, form, and structure. Go to the desk with the ambition of writing that story or novel that’s been bothering you for weeks, months, years. And persist! If you’ve done the reading, follow your gut, and keep at it, you’ll eventually get the work done to the best of your ability.

TD: Tell me about a book or story that helped start your writing journey.

JF: I’m in my fifties now, and when I started writing back in my early twenties, Raymond Carver was very popular in classrooms. I read an anthology of his essays, fiction, and poetry called FIRES that really moved me mostly because (and I don’t always think this is the best reason to be moved or influenced by a book) I could identify with him and the work. In the essays, he talked about coming from a working-class family and being a janitor while writing his first stories. I came from a similar background (my mother’s dream for me was to join the military), and Carver’s simple language showed me that stories could be told in a language free of pretention, fancy words, and whatever it was that I then associated with literature. Carver’s work has a deep authenticity to it. You sense that he’s writing what he knows and that that’s more than enough to give life and interest to the work. That was a revelation to me at the time. Later, I discovered work (Nabokov, Rilke, Munroe, Atwood, Kafka, Morrison, Baldwin, Kundera, Calvino) that was much less familiar and that showed me a wide range of possibilities. But Carver’s quiet brilliance spoke to me and made me feel that I could also be a writer.

TD: Can writing be taught? If so, what are the elements a writer must learn?

JF: Writing can be—and should be—taught. I’ve always been surprised by those who say it can’t be. And yet I graduated from a college in the 1990s that begrudgingly offered only one creative writing course because the English faculty at the time felt that poets and fiction writers were born and couldn’t be “taught” to write. I’ve been teaching fiction writing for almost twenty-five years, and I’ve watched students blossom in one or a few semesters in my classes. Many of my students are now incredibly accomplished writers. One of them just sold her third novel to HBO and, I’ve heard, has quit her day job for good. At the same time, I don’t believe you can teach somebody to be the next Joyce Carol Oats or Alice Munroe or Toni Morrison. Some individuals are obviously more talented, driven, and determined than others. You can teach craft: dialogue, detail, exposition, conflict, narrative modes, point of view, etc. Writers need to learn and metabolize these skills until they are second nature. I also try to teach students how to read as writers, and I give them as much exposure to a wide variety of authors and literary traditions as possible in a semester. I can’t tell students which literary traditions they should work in or how they should write. But I can show them a vast array of possibilities and let them loose to find their authors and their voice(s). Writers learn way more from reading work that excites them than they’ll ever learn in a classroom.

Otherwise, the writing classroom can (and I hope mine does) offer writers community: a group of like-minded peers who exchange work, offer support, and suggest great books and authors to each other. The writing life can be grueling and unforgiving, which makes community essential.

TD: What are you working on now?

JF: I usually work on several projects at once, taking this or that piece out of the shelf, revising it until I hit a wall or finish a draft or succeed in making it the best it can be. That’s when I start crossing out a word only to put that same word back where it was. I’ve got a group of stories that is close to being another collection, though I still need a few more entries. I’m not in a hurry. I’ve got a few different novel drafts in the drawer, though I’m not particularly interested in them now. Since this last October, I’ve been in the early stages of drafting a new novel, which means that I’m obsessed with the core of the project but am still looking for the language, the form, and the structure. I had to put that away this summer while I worked on a story that I began in 2019. I revised it radically, and I hope that it’s done or close to done. But I need to get some of my trusted writer friends and readers to give me a verdict on it. At the moment, I’ve got the nebulous novel project at the back of my mind and am working on a story about my time in Berlin, Germany in the early 1990s that I’ve been trying to write for years. Maybe this summer I’ll finally get a draft out.

***

John Fulton’s is the author of The Flounder and Other Stories, which has just been published and is a Poets & Writers Page One New and Noteworthy Book selection, and three other books of fiction: The Animal Girl, which was short listed for the Story Prize, Retribution, which won the Southern Review Fiction Prize, and the novel More Than Enough, a Barnes and Noble’s Discover Great New Writers selection. His short fiction has been awarded the Pushcart Prize and has been published in Zoetrope, The Sun, Ploughshares, and The Missouri Review, among other venues. He lives with his family in Boston, where he teaches in and directs the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Visit his website to learn more at https://johnfulton.net/.

Tommy Dean is the author of two flash fiction chapbooks Special Like the People on TV (Redbird Chapbooks, 2014) and Covenants (ELJ Editions, 2021), and a full flash collection, Hollows (Alternating Current Press, 2022). He lives in Indiana, where he is the Editor of Fractured Lit and Uncharted Magazine. A recipient of the 2019 Lascaux Prize in Short Fiction, his writing can be found in Best Microfiction 2019, 2020, 2023, Best Small Fiction 2019 and 2022. His work has been published in Monkeybicycle, Laurel Review, Moon City Review, Pithead Chapel, New Flash Fiction Review, and many other litmags. He has taught writing workshops for the Gotham Writers Workshop, The Writer’s Center, and The Writers Workshop. Find him at tommydeanwriter.com and on Twitter @TommyDeanWriter.

by Gillian OShaughnessy | Aug 10, 2023 | flash fiction

The wolves are out again. I can hear them, their hollow wails in the pines, slicing through a storm of snow. It’s my turn to get the wood in. It was my turn last night and the night before and the night before that, too, but Father says I’m mistaken. He’s so careful not to slur his words, I know not to argue. Instead, I offer a skinny smile. He says I look like I’m fed on lemons and sugar, and he’ll fix my face if I don’t fix it first.

I pull on the old boots he keeps by the door. They’re always too big, no matter how tight I pull the laces and wind the ends around and around my ankles. They used to be his best boots, buffed brown leather, the colour of honey. They turned black with age and damp and rot. My father’s eyes were brown once too.

The shed is fifty steps away exactly in this kind of snow when you take into account the weight of the wood sled. I know because I’ve counted. It’s easy to miss the shed in bad weather, and there’s nothing past it but the forest. I’m cold, and I can feel watchful gazes trace my path as I walk. Or maybe I imagine them. I can see thin skeins of frosted breath rise through the trees in the dark, or maybe it’s only the mist. I go step by step. I don’t lose count even as the storm begins to settle.

At the woodshed, the old door lurches on its hinges like a drunk. I feel for the axe near the edge of the doorframe, even before I turn the light on. The sleet and the wind whistle through cracks in the window and a gap in the wall. The bare bulb sways on its frayed cord, and the wood is wet and fetid. I can’t recall when we last stacked it neatly. That was always Mama’s job.

I chop the logs fast. Father says I’m stronger than I look and fierce. It used to make me proud when he said that, I don’t remember why. I pile up the sled and go to put the axe back in its place. In the doorway, between me and the house, stands a thin grey wolf. Still as winter. Looking at me with a steady gaze, its head held low. Fear clutches at my gut like a punch.

Father always said to run if you can from a fight, but if you can’t, go in early and hard, use your fists and teeth and everything. Be wild like an animal, and you’ll win, sure as anything. I used to believe him. The grey wolf glitters sharp under the glow of a luminous moon. I put down my axe and step into the white. Reach out my hand. I don’t remember why.

by Eric Pahre | Aug 7, 2023 | flash fiction

It is not an air raid. Above the city’s steepled church-tops the two planes break from the clouds. Sunlit rain begins to trickle down, and then the smell from wet city streets. The clock tower strikes a warning.

“Judita, you had best head home before they begin,” says the young man selling apricots. He is much younger than her, and she wonders—if she’d been a younger mother— if her eldest would now look something like him.

“Why would I tire myself out hurrying already?” says Judita.

The shoppers point at the coming airplanes, but after all this time, they no longer duck underneath the store’s racks or brace themselves in one of the old plaza’s archways.

There’s that odd murmuring, of the townspeople, of—which will win this time?

Judita doesn’t hide because nobody else is hiding. Of course, they won’t fire at any of the people on the ground. Already the pilots above are likely saluting one another and grinning at their chance to take another round.

Up there, the airplanes shine like coins, wings tipped at angles into the wet sunlight. Engines and propellers chatter. Davit, if he were here, would tell her the engines’ names with some pride, machines named after some bird of prey. When the red plane finds its way out from the sunlight, she sees faintly the many-colored patterning along its oval wings and knows that it is the machine named Pierrougia.

Pierrougia tips a wing at the approaching pilot; a salute. Then it is the opening of both planes’ Vickers guns, the rolling of the shapes in their joust with engines bickering on, then both are away back into the clouds, untouched.

Davit said once, lying on the grass and tearing at a dandelion, that the new airplanes can dodge rain-drops if they so choose. But Pierrougia and the other machines are old and must take the warm water and contend with rusting and their pilots’ slipping on the wing when it is time to dismount.

Up in their apartment, Judita finds her father and her daughter.

Simon is there in the kitchen with the girl balanced on his side, his granddaughter fallen asleep on an old shoulder. The barely-damp breeze pulls at a hanging shirt and carries with it that same lasting smell of fallen rain, and the man shifts slightly to the warm sound of a folk dance on the living room radio.

It is as though Simon is a new father himself: no longer Judita’s but a doting man, smiling with the sleeping girl, reborn in this way. Judita finds a large wicker basket at the foot of a cupboard, and begins corralling items, quickly.

“Still in some hurry?” Simon whispers.

“How was it today?” Judita says, and her father just looks down at the sleeping girl and raises his eyebrows, nodding.

Judita looks at her daughter. Why does she somehow feel like a grandmother and not a mother—and how many grey hairs will her girl find when she begins to truly see? Will it be the handful, now, or the head of a withered mother who cannot run with her and speaks with the voice of Judita’s own mother?

Judita ducks low to reach out and close the window, and there are the planes again up high: Pierrougia’s red hull is blazing with stars and in a wheeling whirlwind, passes. The foe’s guns begin to roar again.

Pierrougia weaves through it all and finds its way to double back, opening fire, and there is that sharp clang of some stray bullet striking the adversary’s hull. Both planes vanish again, behind the clocktower. Rain, again, briefly falls. Judita smells petrol. Her daughter sleeps through it all, nestled into her grandfather’s shoulder as he sways.

Judita is in the rocky field not far from the city, the sun shining through the clouds. The scattered boulders are damp: pebbles, gleaming. She opens her basket and unfurls the blanket atop smooth grass.

Judita arranges the pieces of food, pouring an extra glass of wine at the picnic-site. If she sets it all up like this, with everything in order, then he will know just where to land.

The machines do return: Pierrougia, at tilt. Turning and turning, rising like a merlin in a high thermal. The sound of engines is the only thing; then guns that fire again, from both sides, and the adversary is totaled with the flames bursting across its metal span as it twists away down into the wooded marshland. Pierrougia tips a wing in salute again.

But the red, starry airplane has taken it, too, and then Judita’s stomach has a slight turn as always as she sees the plane wilting from the sky and trailing black smoke.

Pierrougia comes down hard, scraping to a stop at the rocky edge of the field, the pilot clambering from the airplane as flames begin to bloom at its propellor, him popping up the cockpit’s glass and sliding down the wet wing. The pilot, leather-capped, throws his shattered goggles into the wreckage.

Pierrougia burns again. The pilot wanders towards Judita’s picnic, stretching his arms and stuffing gloves into his pockets. Steam rises from the metal of his harness that he just then begins to notice, and he unfastens his belt, the heavy pieces falling away to hiss in the spring grass.

He sits, and she hands him wine, saying, “Are you all right this time?”

His eyes are great and cloud-filled, ringed by the bruises of heavy goggles.

“Well enough, he says.” They drink.

“You nearly woke her up this time, fighting so close to the city,” Judita says. “You could fight somewhere else next time.”

Davit is famished and digs into the plate of bread and cheese, thumbing the pit from an apricot. He looks older, there, but Judita must remind herself that he has gotten older since they were married.

“If we fought up in the mountains or down across the marshland,” Davit says, “who would see us?”

Recent Comments