by Lucy Zhang | Oct 30, 2023 | flash fiction

Mei turns into a flower whenever we touch. Her pupils blossom into glossy hibiscuses—hues of red and peach and white. They grow from her pores and eat through her skin, treating her flesh as the soil that nourishes them. We tried different things: kissing, hugging, hand-holding. Now, we avoid most skin-to-skin contact because I fear Mei will become a silent flower-doll-corpse rooted in the earth.

Mei wants to have sex, though. She likes the feeling of me running my fingers over her sides until flowers begin blooming along her rib cage. She likes when I touch my mouth to hers until my tongue no longer feels the tight muscle of her tongue but rather the bitter yet fragrant taste of petals choking me. The flowers grow faster the longer I touch her, filling her mouth until she can no longer breathe, although I suspect that in this state, she has no need to. Several minutes later, she reverts to her original self and asks why I don’t stroke her for longer periods of time. She hasn’t seen herself in the mirror. You can’t make love with a person sprouting flowers out of their eye sockets, mouth, limbs, and who-knows-where-else. I’m not even sure Mei is capable of having sex, her body a hibiscus harvesting ground.

“Will you at least hold me then?” Mei asks, turning to the other side so she doesn’t face me on the bed. I indulge her request briefly since I feel bad saying no to everything else. I hold Mei in my arms until the first flower blossoms completely. She cries when I carry her to her bed and close the door as I leave so the flowers can wither away properly.

I don’t crave touch like Mei does. Supposedly when I was born, I wouldn’t stop crying until my mother put me down and took several steps back with her hands raised as though to promise she’d do no harm. It creeps me out a bit: someone’s hands clammy and tight over your limbs, suffocating your skin. Skin is meant to breathe, lined with pores that resemble pathways to the outside.

Whenever I stroke Mei, she purrs while I shut my eyes and try not to focus on her limbs. The moment I stop feeling the slick sweat, my fingers slightly moist as they flow from uneven patches of flakey skin to silky petals erupting over her body, I retract my hand. I would rather touch the flowers, honestly—they’re softer, more delicate, like clouds cushioning the pads of my fingers instead of the skin and flesh dragging them down. I tell Mei that making love resembles drowning and that she wouldn’t like it at all.

“Do you think this happens because I’m actually the descendant of some god?” Mei asks, gesturing to the half of her face that has been overrun by the roots and tiny buds yet to bloom. “I’m just built differently and will probably outlive a regular human. Like a god, you think?”

I look Mei in the eyes even though all I see are flower pistols and the bulge where their ovaries grow. She insists we make eye contact when we’re intimate, but when I look away, she rarely notices. I suspect she can no longer see when the plants overrun her pupils.

“You’re probably closer to a god than anything else I’ve seen,” I say.

“Really? Do you mean that?” Mei places her hands on her cheeks to feel the petals and plucks one straight from her eye socket. “It doesn’t hurt at all. This has got to be nature’s way of protecting me.”

“From what?”

“Everything, I guess. The world is always out to get you, you know. ”

Mei likes to speak in ambiguities. She can’t even explain to me what she wants from the grocery store—“something sweet” or “something that makes me feel like using three spoons with two hands”—so I’ve learned to translate her needs over the years. It’s not an exact science though, and sometimes I misinterpret her words and think she wants to sleep when really she wants to paraglide, or that she wants feta cheese instead of kimchi. I used to think Mei didn’t know what she wanted, but her furrowed eyebrows and slumped figure whenever I got it “wrong” meant a “right” and “wrong” existed. She wouldn’t say it out loud—only sigh and grumble and collapse into herself like a crushed foil sculpture.

“But I’m here to protect you.” I swing my arms around Mei, wrapping her so her back is flushed against my chest. The flowers grow from beneath her bra strap, forcing their way over the elastic until my body is what’s crushing them rather than the spandex. It’s a light touch, almost unnoticeable with how thin and delicate each growth is, but they tickle my stomach and spill over our sides, growing larger with vines winding along our arms and wrapping around my wrist.

“Do you know what kind of flower these are?” I wonder.

Mei twists her head over even though she can’t see in her state. She can’t even speak anymore, her mouth stuffed with petals and hairy stalks.

I withdraw, pushing her to the side of the bed so she has a chance to let the flowers wither off and her organs regenerate the gaps filled by hibiscuses. For a moment, my hand slides through her ribs where a bouquet has now shriveled, leaving caved-out organs and half-decayed lungs, more shell than flesh. I scoop away the wilted plants, holding them delicately in case they can still feel, in case the pleasure Mei desires carries over to her remains, alive and thriving like tiny gods in my palm

by Vincent Anioke | Oct 26, 2023 | flash fiction

I’m giving Kayode Last-Name-Pending a pretty accomplished blowjob in the back of my rented Subaru when Jesus Christ returns. He’s a theatrical man (Jesus, I mean; Kayode, I met minutes ago at a bar), announcing the onset of rapture in a whirl of lightning and wind. No trumpets, though, so Ma was only half-right. Rapture lasts five seconds. We are flanked by mangroves in a deserted stretch of the woods, so we miss the immediate consequences of sudden vanishing. Driverless cars mowing pedestrians, leashed dogs barking at empty air, spines crushed by panicked feet. As the skies calm, we separate, our faces alarmed in the moonlight. We do not know yet that we have been left behind.

**

Kayode says that one hundred years ago, a flutist moved to his father’s village. By day, the flutist was a nuisance preaching about the One True God, delegating Amadioha, Agwu, even child-gifting Ala to the realm of horseshit. By night, though, he played his flute at the square, finely carved wood bewitching every woman and child to dance. Soon after, verdant rows of maize blackened overnight. Livestock collapsed and rotted. After the streams turned a foul red, swallowing swimming children, a flock of famished men encircled the flutist. No villager intervened. Perhaps they wanted to see if his special New God offered protection. They watched as his flute shattered beneath boots, as snot bubbles popped above his pleading lips, as the cutlass flashed. His body was plucked clean for meat until the blight subsided, but there remained–forever–a silence where his flute once sang.

**

Cars and keke napeps stretch backward into a smoke-plumed horizon. Cooking flesh reeks off a danfo bus burning on the median. Kayode disembarks from the Subaru, and there is no question that I must follow. The roadsides are clogged too. A gray-haired man drops to his knees, arms raised high. Were mu bikozie, he shrieks at the clouds. But they do not take him away. Morning light punches holes in the sky when we find the bungalow with shattered windows. The door is ajar. Kayode can’t move inside until he takes my hand. We find rectangular imprints on floral wallpapers where photos once hung. Empty closets and freezers too. A heat-charred pot remains. Shelves filled with books about the Biafran war. A pink bicycle slants lopsided against a pink door. And in the cobwebbed, unfurnished basement lies a motionless cat. Poison, Kayode thinks, bending to stroke its patchy fur. The words trapped in my throat tumble out as vomit. Kayode takes a step back.

**

Kayode, too, has wandered the lands searching for a nameless thing. Not family because he learned the worth of blood when his parents found his journal–those detailed sketches of men on men–and decided to send him to some camp. He emptied their safe of its naira stacks while they slept and vanished forever. Not intellectual fulfillment because he only lasted six months at the university in Kaduna. Not hedonism either. When the cruise boat left the shores, a handsome man on the deck bar introduced himself in a way that suggested he’d stick to Kayode’s side all week. Kayode jumped overboard, swimming and swimming until he was back on solid ground.

**

No new storms rip the skies apart. The bungalow owners do not return. Kayode prefers the floorboards to the bed, so we shift as one against the hardwood. Sleep is elusive, so we memorize the landscapes of our lips, which soon becomes the kind of mutual crying that persists until no tears are left. His breathing is ragged. I hold his air in my lungs. We take long walks to chase the setting sun. We return from scavenges with carts of canned tuna. We find barbershops turned churches, crowds overspilling onto several lanes of gravel. They sing with their whole bodies, sweating, wailing in tongues. Atop a bridge, four men link their arms and jump. In the splatter, it is impossible to discern what belonged to whom. We argue: friends or brothers? Maybe strangers. There is a video online of a famously antigay pastor vanishing mid-sermon with half his congregation. Turns out Ma was right about that too. Kayode turns off his phone and goes down on me, his motion surprising in its confidence.

**

I have fled men I loved, men who loved me, brothers, sisters, my own potential. I used to drive hundreds of kilometers to nowhere. On the plains of Sokoto, at the last full moon, I found a forest. There, I found a pit full of dead parakeets, but for one on the edge, still fluttering. When I clasped Ifesinachi in my palm, he flapped his wings as if trying to flee. I wiped his bloodied beak with the edge of my sleeve. On the drive to the nearest veterinarian, I thought of how discovery can be so particular as to feel predestined. How predestination can feel like purpose. This had to be mine–nursing Ifesinachi to full health, granting him new life within the remnants of my world. Miyetti Veterinary gleamed in the distance when Ifesinachi squawked one last time. Still, I went in, plopped his dead body on the desk of a stunned receptionist–he is my whole world; fix him now.

**

There are no stars tonight. We are swaying barefoot on a hammock in the backyard when I mention my renewed fear of dying. Kayode Salau floats a theory that has been on his mind for a while. Maybe each of us belongs to the domain of a certain force. Like the raptured souls belong to Jesus, but the rest of us belong elsewhere–isn’t that why we exist? To solve for x, even if the search destroys us, makes broth of our bones. I want to say we don’t exist for any reason, but my ear is pressed to Kayode’s chest, and beneath the skin, there is the unmistakable melody of a flutist’s song. We rise–me and him–and dance until our stone-pierced soles bleed.

by Fractured Lit | Oct 25, 2023 | news

25 stories made it to our shortlist for this contest! Thank you all for trusting us with your writing! Judge Sara Lippmann is now reading and will make her choices soon!

- Pairs

- possible future for our daughter #683

- Rowdy Yates Slept Here

- Roadkill

- Is Now and Ever Shall Be

- For a Short Time Only

- Vandals

- If we name it Mittens, can we please keep the food delivery bot, please?

- Missed Shifts

- The Kaiser’s Bullet

- After Sabbath, Now Laugh

- We Mistakenly Think It Keeps Growing

- Unwrecked (Notes on Year IV in the Deep Caribbean)

- Candied Lemon

- Intertidal

- In All The Loveless Places

- My Mother, the Water Monster

- The Girl Made of Dirt

- Piel Muerta / Dead Skin

- Cheerful

- Stanislavski’s Fly

- Four

- Fullness

- To the Next Tenant, I Have Left

- Snagging Blanket

by Melissa Llanes Brownlee | Oct 23, 2023 | micro

I laugh at your need to keep your knees covered, shorts too long, pants too short, colors muted and dark. At night, I unpeel you, uncovering hair grown along scars from childhood scrapes along coral, swirls in patterns of fronds, cerebellum, a reef of skin for me to swim over.

You mock my cravings for raw chili peppers, burning my lips with each seed, the oil, a glistening inferno on my tongue. At night, you pluck each tiny red body from the bush, run it along my skin, memories of taunts and screams, sugar, milk, bread, a conflagration never quenched.

by L Mari Harris | Oct 19, 2023 | flash fiction

Someone picks at her nail polish. Someone keeps checking her phone. Someone complains it’s too hot; someone asks how much longer this is going to take. Someone wants to grab pizza when it’s over. All the someones agree on thin crust, because prom is right around the corner and their dresses have already been bought. More than one of the adults standing in the back row turn to look at all the someones chattering about thin crust. Someone feels their eyes on them and tells the other someones to keep it down. Someone remembers the yellow polka dot two-piece her mom bought her that summer, how she tugged at the material, willing her body to spill over like her big sister’s did. Someone remembers how hot it was, how they all raced their slick porpoise bodies through the water, orange buoys bobbing in the lake, first one to touch a buoy winning the round, again and again and again, until all the someones’ moms ordered them out and slathered more Coppertone up and down their scrawny bodies as they hopped from foot to foot on the burning sand. Someone remembers eating so many hot dogs she puked behind the concession stand, says she missed all of it, never saw a thing. Someone remembers a van at the far end of the parking lot. Someone tells her she watches too many crime shows. Someone wonders if it’s possible the girl could be living with a new family somewhere else, says she’s heard of that happening. Someone who always has an answer for everything says after all these years statistics show it’ll probably be hunters that come across the bones one day. All the someones can’t think of anything so terrible as that. Someone asks, Was it Marsha? Marci? Melinda? Someone says, No, dummy, it was Melissa. All the someones clamp their hands over their glossed lips, because suddenly it all feels so funny and overwhelming and when is this thing going to end plant the tree and unveil the plaque already, which makes someone want to forget she’s stealing more and more of her stepmom’s little blue pills, someone’s big brother is heading back to jail, and someone’s parents are fighting in court again. Someone wonders if someone loves her back, she’ll ask later when it’s just the two of them left at the table, their reflections shimmering and dancing and alive in the pizza joint’s windows. The night beyond like someone else, distant and dimmed.

by Chloe N. Clark | Oct 16, 2023 | flash fiction

On the highway at night, every other car is filled with ghosts. (you could be a ghost, too, if you tried) They flicker in and out of view under the highway lights, the headlights of other cars. Children asleep in the backseat who sit up to look at you. Or they stay in dreams. Or they disappear as soon as you get close enough to see their faces. (you were young once, asleep in the back of cars on family trips, have you ever felt that safe again as the car heater on, hushed voices of your parents, the steady thrum of the car?) A car will ride alongside you for a few miles at a stretch. The driver will be your long dead best friend, her hair in a braid, her eyes on the road. She will be wearing her favorite shirt, the one from your favorite band, the show you’d been to together, you’d scream-sung along to every song. If she looks over at you, the spell will be broken, and she will be someone you don’t know. Hope she doesn’t look over, keeps her eyes on the road. Eyes on the road. (you could keep your eyes on the road, too, stop looking into the lives of strangers as they pass you by, but who would notice the ghosts then as they drive alongside you?) The man walking alongside the highway is shirtless sometimes, and sometimes he’s dressed all in black, and sometimes he’s a child. You will say, that’s so dangerous, but whoever is driving with you won’t have seen him. They’ll mumble, with sleepy breath voice, are you sure there was a man there? The man will nod at you if you see him, he’ll smile as he knows all your secrets. The man has looked into every car at night, driving the highway, he has seen everyone in the dark. (you saw him once as a child, from out of half-closed eyes, he walked the highway, your dad was driving, your mom was asleep, you looked the man in the eyes, and he thought you were sleeping, so he didn’t nod at you, didn’t mark you down). Alongside you, the car of your ex-boss, your favorite teacher from elementary school, your great-grandmother, all the dead driving forward. If you look over, your ex-boss will be eating French fries as he drives, licking salt from skeletal fingers. Your favorite teacher died too young, but you were a child so she seemed old. She will be singing along to the radio. (you heard her once singing as she cleaned the classroom when you came in from recess early because of a tummy-ache and you stood in the doorway to hear her, her voice was night skies and the top of the Ferris wheel). All the billboards and highway signs say you’re almost home, but you could stop here anyway. You could go through the midnight drive-through and get hot and greasy salty food and chocolate shakes and fill your mouth with flavor to have something to do. Stay awake, the signs say. We can help, they say. If you lived here, they say. But you’re not home now, not yet. (you could be home now if you tried). Your long dead best friend turns up her radio, and you can hear your favorite songs out her window, if you looked at her, would she see you too, you wonder. The highway shrinks and shimmers in the dark. All the trees and ravines and fields and houses are asleep. Their shapes in the dark are deeper than the black of night. Keep driving. (you could be a ghost, too, if you tried). Keep driving. Someone is turning in their sleep waiting for you to come home.

by Greg Tebbano | Oct 12, 2023 | flash fiction

That morning Judy brought a television to the bakery, one of those little tube driven units. It must have been twenty years old. Back then, portable meant eighteen pounds. We plugged it in next to the coffee maker, pulled the antenna to length, and looked into Manhattan through that black and white window—each suit jacket and blouse a gradation of exhaust, the sky a shade of overcast. Only the dust was its true color—no color—and when you couldn’t see it, you saw people choking on it and spitting it onto the blacktop.

Judy rolled the dial from six to ten to thirteen—the networks all showing the same—as her leg bounced and her hand with the dishtowel traced the same circle of countertop where nothing had spilled.

“Leo’s cousin is volunteer FD,” she said. “He’s already on his way down there.”

Judy hired me that summer, I think, because I reminded her of her son Leo, a boy who kept washing ashore on this beach or that, whose ship it seemed knew only how to wreck. She once told me, eyes fixed on the floor, how he squatted on state land in a teepee through the three longest months of winter. I met him a couple times. All we seemed to have in common was the false belief that society had secret emergency exits hidden away somewhere. Only Leo was brave enough to go looking for them.

As Judy stared into that cloud that had once been a building, I asked her, “Leo wasn’t—”

She grabbed my arm and squeezed the blood back towards my heart.

“No,” she said. But on a day when everyone had heard from their most beloved, she hadn’t heard from hers.

No one came in that morning—not for sandwiches, not for biscotti and the coffee to drown them in. Judy and I kept busy. We washed the floor-to-ceiling windows with a squeegee and a bucket of suds, and the voices on the television told us what we knew, what we didn’t, and what we were still waiting to hear.

Judy kept talking so we could listen to something else. She told me how she met her husband. He was alright, she said. But really, she had a thing for his car. She told me how Leo was born in their bathtub after twelve hours of hell.

And how long would this hell last, she wondered.

I asked about the cross she wore on a chain, that was always throwing light in my eyes. Yes, she believed in god, she said, but she didn’t trust him.

When Judy pried, I told her about my recently acquired English degree. How my parents were tapping their fingers, waiting to see how useful it would be. That was the first year of my life when the calendar turned September, I had nowhere to be. It was a panoramic feeling. Every door was suddenly an exit. At the time, I mistook it for freedom.

As we talked, the windows disappeared under our work, became sky and concrete, and the elms planted by the city. I watched the light at Main and Church change from red to green for no cars; the intersection became the province of crows who pecked at the tar until it yielded up some overlooked kernel of sweetness. Later when I went back for more towels, I found her sitting on the employee toilet with the door open, head in her hands.

“Don’t become a parent,” she said. “It’ll shorten your life.”

Above her were stacks and stacks of folded white towels. Enough to dampen and dust the entire store. And perhaps when that was done, we would start on the street.

Whenever the phone rang, Judy jumped. It was never an order for pick up. It was her husband or for me or the bakers, acquaintances just checking in, as if New York could stretch this far up the Hudson, backwashing into our quaint streets, up to our painted shutters—a brackish tide. As if it hadn’t already. It was a day when no one said, well, the sky isn’t falling.

A baker came out to deliver a finished cake to the case, a chocolate mousse that held a face’s reflection before one blew out the candles and away the year. He watched the TV with us and asked what we’d learned besides the temperature at which jet fuel burns. Later someone told me that day was the beginning of news all the time.

The baker asked Judy if she heard from Leo.

“No,” she said. “Though, you know, there was this one ex-girlfriend. From the Bronx. The one that got away.”

Still, he said, the odds were against it. But what did the odds say about everything we had seen so far on the little television, the impossibilities it had pulled out of the ever-thinning air?

“Sweet girl,” Judy said. “With a heart-shaped face.”

I could see the dryness in her eyes. As if she hadn’t blinked since breakfast.

“Judy, go home,” I said softly. “I can close up.”

But she shook her head, and we washed the pastry case again with Windex on paper towels, until the glass gleamed, a French dictionary of pastries under there, the butter from Normandy, Umbrian chocolate, dates from the Saudis, all of it battered and whipped and proofed, grown in the ovens overnight by Amis, a hermit who drove down from the mountains to bake the city its breakfast. That day no one had an appetite for anything but speculation, and the pictures, those doughy pictures, horrible and transfixing. So this was hypnosis, I thought. Broken only by the ringing of the phone, by Judy explaining that he wasn’t—could not have been, no way on earth—in the city, in the swirling dust that the wind blew past Montauk out to sea, and that the tide would, again and again, bring back.

by Amelia Golia | Oct 9, 2023 | flash fiction

If I could, I would pray, but God has no use for a girl like me.

“Non mi tange.”

During labor, my mother had an auditory hallucination that Dante was speaking to her. Dante the poet. He told her to name me Beatrice. Beatrice was not affected by the flames and misery of hell. Or so she claimed in the second canto of Inferno. Beatrice was not God. She was a woman. More woman, even, than God.

In the food court of a mall, my boyfriend Ethan broke up with me over a soft pretzel. It was kind; I put my face gently into the soft pretzel, and he stroked my hair, and I almost fell asleep. I said, I understand completely. He said, Hey, get your face out of the pretzel.

I sat up and flicked the salt pellets from my cheek. I’m curious, I yawned, before you go.

Right.

Would you say you prefer Sappho or Dante?

Yeah, but why only those two, right?

But what if it was those two? Which one?

Sappho, I guess. I’m not into Christianity.

But Dante was writing about other things. Grief. Power. Love.

And it all comes back to that Christian overview, right?

I made a noise like a game show buzzer, and Ethan’s nostrils flared. Wrong.

Ethan found his own way home. I’m not sure how he did it. We were in a suburb in New Jersey. As for myself, I had a rented Smart Car for the day, for no reason except that I was hoping it would make whimsical fun a greater part of my life. I offered him a ride, but he cast a quizzical eye on the blacktop and said he was hoping to check out the parking lot a little bit more. It had been a while since he’d seen one. He set off, muttering about graduate school.

Jerry, my boss, who was fifty, told me it had been silly to waste my time with anyone under thirty. But then he said, you know what, maybe I’m wrong. We were at the Harvard Club, dining on his account. To be honest, it seemed unlikely that he was wrong. I sipped on a cucumber water and thought about how pleasant it was to eat lunch in what seemed to be a lighting design inspired by Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Soft, red, apocalyptic. Lantern lit.

If you were a nocturnal animal, I said, who would you be?

He squeezed my thigh beneath the table. A nerve misfired, and he squeezed his sandwich, too, and all the chicken salad fell out of it and onto his lap. Oh my God, he said.

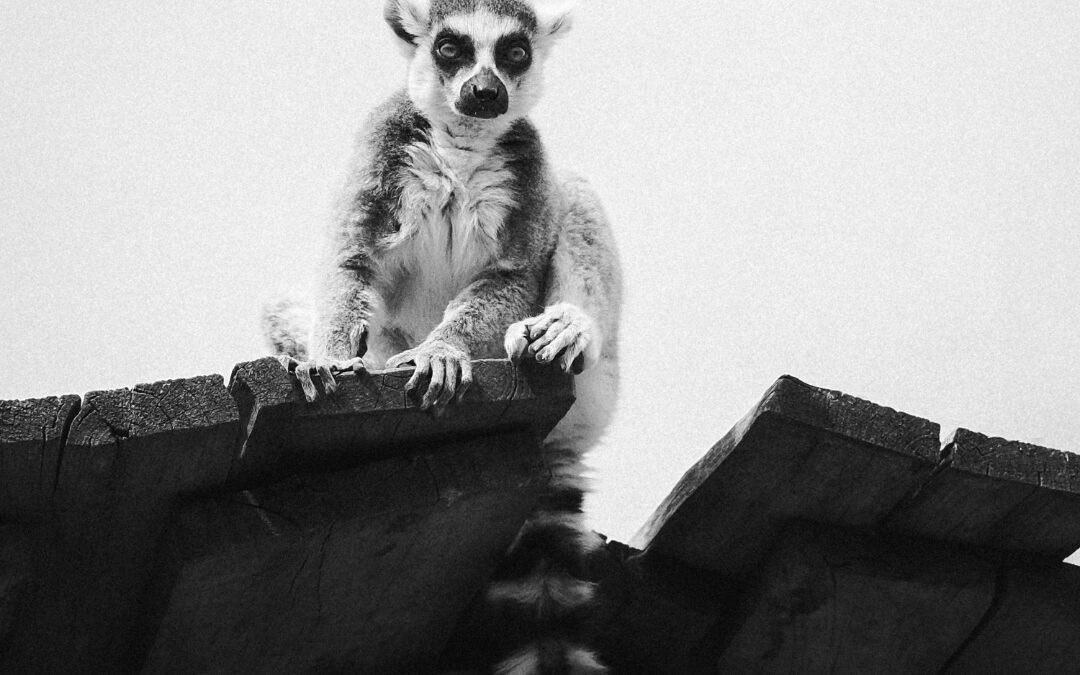

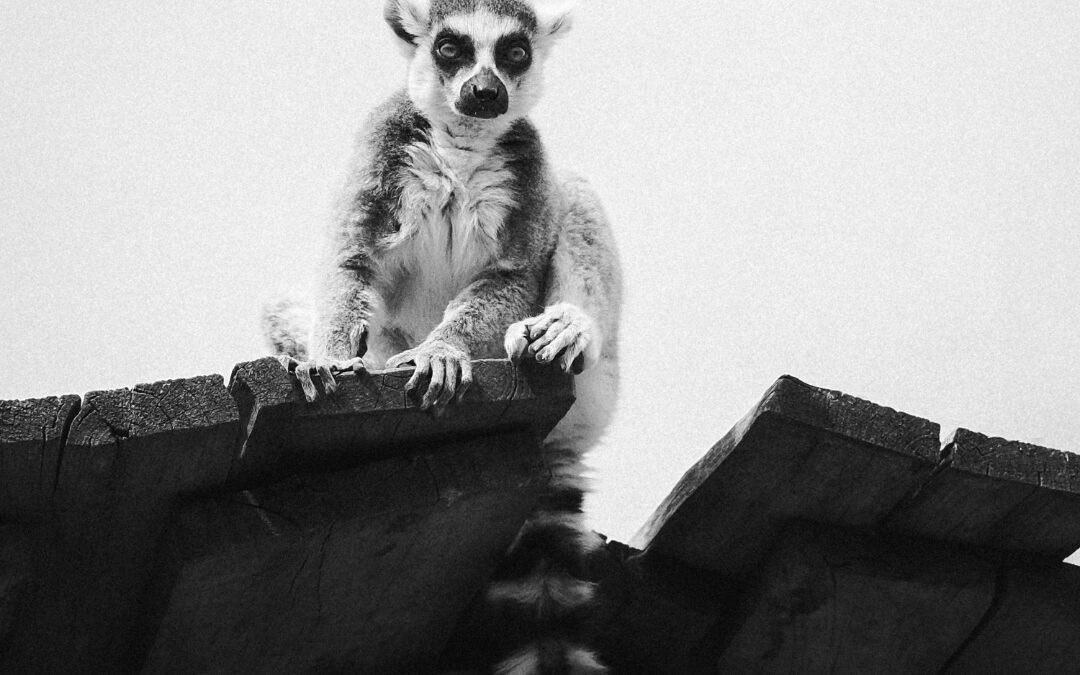

I told him I would be a lemur.

A lemur. He wiped mayonnaise off his jeans. He motioned to a waiter. A lemur. He chuckled. I was good at helping him recover from life’s little mishaps. He smiled affectionately. His eyes were pointed at the waiter, but that was all part of our many precautions against total ruin. I knew the smile was meant for me.

A lemur. Jerry looked at me, concern crushing his forehead, the bumps of time that pressed upon his brain, and in the crannies of his eyes, I saw a stirring. Jerry looked at me, not as though for the first time. In that look, there had been none of this. In the first look, only the placid lake of shy wanting. Not these things, wood mites of disgust.

I’m kidding, Jerry, I said. Obviously.

Enough of this. Non mi tange. It doesn’t affect me. I’m plummeting through the endless depths of space, not hung up on God. Little ol’ me! In the office, unease wound its way through my cube. My face was hot like fever, but my blood stayed cool. I was cc-ed with abundance. Jerry used to hold me like a little duckling, shooing away the angry black flies of emails, telling everyone that he was the only one who told me what to do. Now, with eyes despairing, he—

Enough about Jerry. What can I tell you? When I introduce myself, people notice me. They think it is possible to fall in love with me after I’ve died. My name is unusual and beautiful. They whisper it, a little question.

? To you devoutly

Dante prayed.

But at the end of the day, I am a woman. The silliest thing of all.

Calm down, I say.

Not that Beatrice, I say.

Another Beatrice, I say.

by Kelley Albright | Oct 5, 2023 | flash fiction

He left his scent behind. It melted into pillows, sheets, and shirts crumpled onto the floor. It even soaked into my skin. Once, I swore, it had made a home in the deepest caverns of my nasal cavity, and that’s where it lived for days. When it finally packed up and moved along, I was lonely. I longed for its return.

It was earthy, mulled, and laced with a cooling effect. It sprang forth strongest when I tickled the surface of his neck, sorta like when I drag my claw tiller across fresh soil. It intoxicated me. Provided a temporary high coupled with its serene, calming effect. I huffed it when it was present. I grew anxious when it disappeared, craving its return. It consumed my thoughts.

Pretty soon, I needed it, day and night. It hung heavy on me when he came ‘round, like a dust cloud, clinging to everything in its path. I quit showering after he left. Washing it down the drain seemed frivolous and risky. When I finally had to succumb—in order to enter the world—I mourned the loss, watching the water disappear down the drain, taking with it the last remnants of that heavenly scent.

I even started tasting it. Thinking, perhaps, filling another one of my senses with it could provide an even stronger hit. Turns out that was a mistake. Just tasted like chemicals, or opening your mouth wide while walking through a sterile environment and scooping in all the antiseptic compounds until your saliva was pure ethanol. It nearly turned me off the scent, but just for a moment.

I knew I had a problem when I was shopping for the scent on my own. The few times a week I got a hit were no longer enough. I needed a re-supply in-between visits. If he weren’t there to provide it, I’d drown myself in its mystic aura. I started with a small bottle. That would be enough to keep me going. Soon enough, I was spraying it daily. I was covering everything in my house. I started to wear it myself. Thank God for work-from-home. I could bask in the delights alone and hide in my obsession.

He started to notice. “Am I wearing too much of this stuff? I think I smell it everywhere?”

“No!” I answered too quickly. “I don’t even notice it anymore.” Crisis averted.

That is, until he left me. During the speech, I sniffled liberally. We were out back, in the garden, so the pollen and tears brought that on naturally, but I also needed the extra inhales. Sure, I had my own source now, but the truth was, it was different coming directly from the bottle. I had learned that it was really the co-mingling effect I craved. Something in his sweat combined with the artificial and created the exact scent I needed to survive. It was my fertilizer, and he was taking it away from me. I couldn’t allow it to happen. He kept explaining the reasons, and my mind began to race. Butterflies and earthworms. They both roam through gardens, but do you know the difference? One flies above land, taking what it can from the above-ground world, reaching deep within the beautiful parts and draining them dry. The other slithers underneath the growth, feeding off the decaying parts left behind.

I wasn’t thinking about how to get him to stay, at least not the him that could stay. I don’t know how the whole thing happened, and I can’t say, certainly not now. There was a shovel still in my gloved hands when he came over for the talk. My corporal body reacted. My mind hadn’t even caught up yet. My body knew it had to be done. My mind’s remaining concern was whether the scent would still emanate from the decomposition. Maybe for a little while. Or, maybe, it would mix in with the soil, and every time I till the garden, the interweaving of what was once beautiful and what was now decaying would produce a new compound altogether. I wondered what perfume might stem from this new concoction and how I could continue its production.

by Jo Withers | Oct 2, 2023 | flash fiction

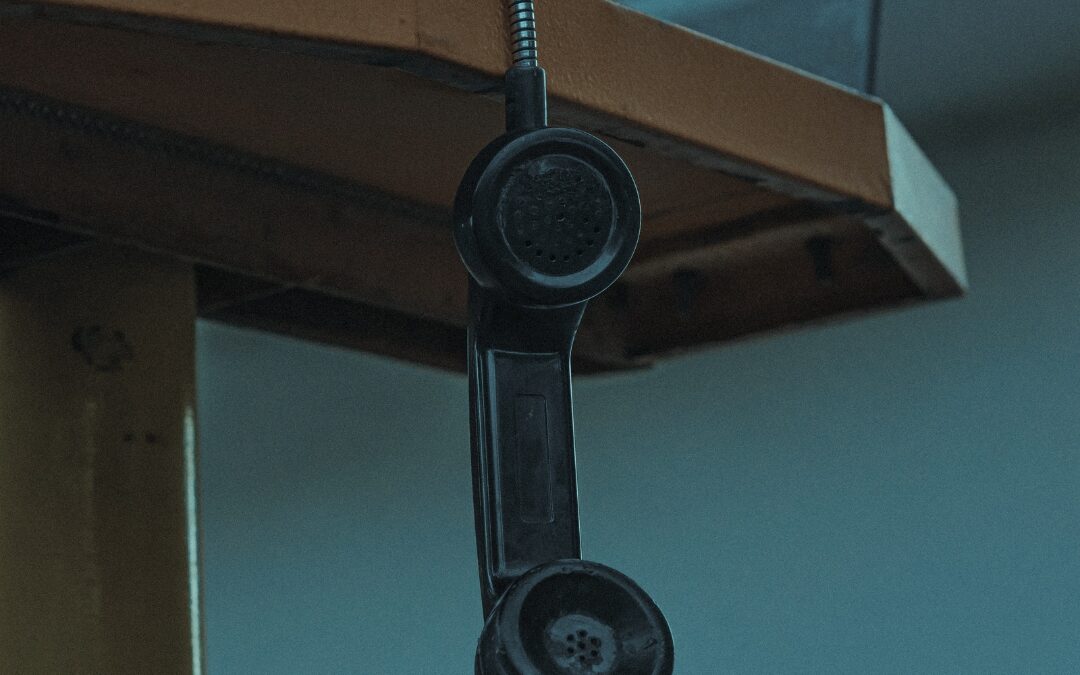

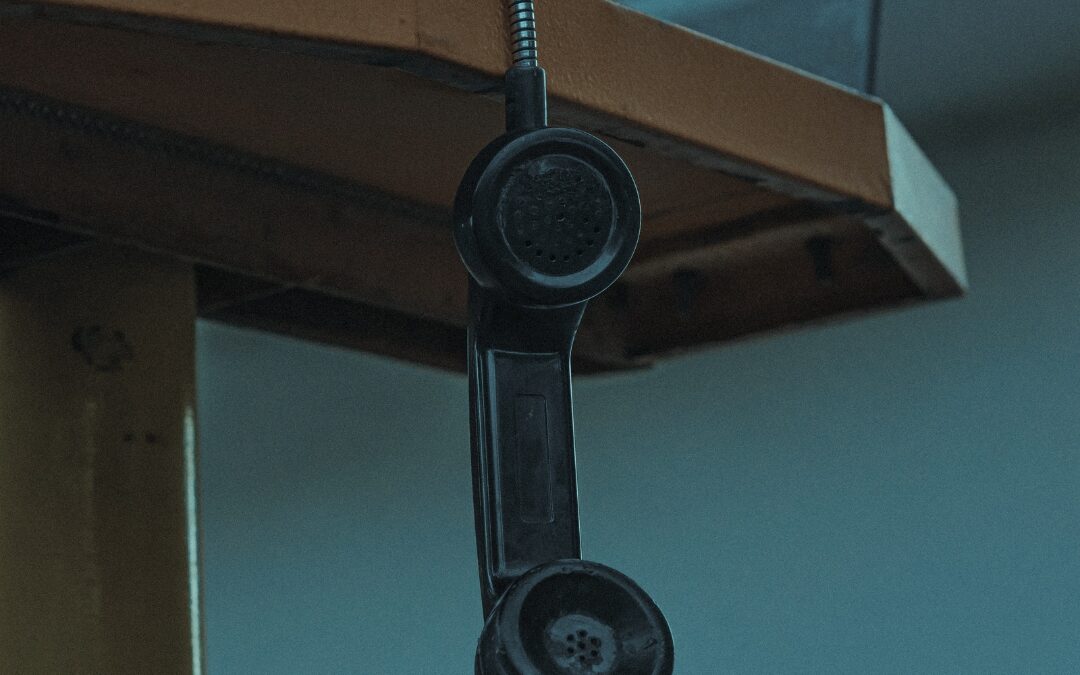

The Lifeline operator refuses to take my call when she realises I’m already dead. I tell her my name, and she looks up my file. She sounds angry, tells me to hang up, says she’s in the business of helping the living. I beg her to stay on the line, tell her it’s not enough, that I don’t feel dead enough. I ask her how I can die properly so I’m numb and cold and never. She tells me the guy I spoke to last time needed months of therapy when he couldn’t talk me down. She clicks her tongue, and the words spit out fast with none of the usual, purposefully non-triggering, tranquil sympathy. She says the whole office heard the crunch as I hit the ground, that all he could imagine was my head on the floor, brain splattered in a kaleidoscope of light and dark like a Jackson Pollock number eight.

I am not dead enough. There are so many things I can still feel. When the rain is heavy, I feel prickles of damp steam fizzing like an electric current. In crowds, I can feel people’s bubbling hatred, the way they bump into strangers on purpose, a slow, simmering rage passing like an ice-cold weather front as they push by. I can feel shadows now, can hold them, and manipulate them like ribbons. And I feel all the things I felt before, I feel the stone-weight of chronic isolation where I used to have a gut, feel the tumorous mass of loneliness where my temple used to be.

I revisit the bridge where I died, throw myself over the edge again and again, forwards, backwards, sideways. I experiment with different poses, arms outstretched like an angel, arms pointed down like a broken arrow. It takes longer to reach the ground now, there is no noise when I land. I lie in the ditch at the bottom, wondering if anything has changed, hoping I’m a little more broken, a little more empty.

I think my mother can see me sometimes. I follow her as she goes about her deadbeat day, grocery shopping, cleaning, going to church. I don’t know why she sees me sometimes and not others. One time she suddenly stares right at me in the cereal aisle of the supermarket, drops her basket, and runs from the store. I wonder if she sees me as I was when I was alive or whether I manifest with my head caved in, parts in all the wrong places like a Picasso portrait.

I follow my mother to her therapy sessions. She goes once a week, spends the whole time talking about me. She never cries, she says it would be self-indulgent – says that’s why I’m dead, that she was selfish, I’d still be here if she’d done x, y, or f. I sit next to her on the mid-grey couch, picking at the textured cream cushions. Cracks of light from the nearby window illuminate the white bones of her sunken cheeks. I think about how much I hate her, how much I despise her state of extreme inertia, how jealous I am that she is so deeply desensitised she’s catatonic.

I start to follow the Lifeline lady instead. I wait outside the office block every night and follow her home. I can tell the days they’ve had a jumper or a wrist-slitter. She walks different, holds her handbag closer to her body like she’s hugging herself. She lives alone. She has a cat. On the bad days, she talks to it, tries to entice it to her lap. Sometimes she’s worse on the nights they’re still alive, she worries that they told her what she wanted to hear, that she should have kept them talking longer, that they won’t bother ringing next time, they’ll just neck the pills. Statistics tell her every time they ring, brings them closer to the end. She eats dinner, feeds the cat, takes a shower, washes away the worry and decay. In the morning, she will dress and go to work, strive to maintain the balance between the living and the dead.

I return to my bridge. I stare over the edge for a long time, wondering if there are any parts of me still left in the earth below. As I leap over the barrier, the rain starts, the dark sky catches me, buffering me through pockets of air, buoyed by cloud. I weight myself with anger, press down against the rain, knowing it is far too late for me to learn to float.

Recent Comments