At eight I was rich and powerful, controlled railroads and electric companies. A banker, I embezzled rainbows of cash that I flashed at the twins while our parents slept in. Let’s play restaurant, I’d say. Jacob, you’re the chef. I’ll be the customer who leaves a big tip. Even at six Jake made an elegant French toast. Syrup, Madam? he said. Please…allow me.

Later, after he washed my dishes, pocketed the orange dollar bills I left on the table, we played The Game of Life where convertibles motored across the board as we acquired advanced degrees and children and wealth. Our favorite part was the oversized spinner, the ratchety clack when a flick of thumb and forefinger turned it into a blur like Jake when he tried to make himself dizzy. Sometimes, if my fortunes lagged, I’d take his car, heavy with pink daughters, blue sons, and oil rigs, place it right on the spinner, and launch that ragtop into outer space, tell him, oh, so sorry, but his family had landed on Mars, the red planet.

In the end he never left home. He is upstairs now in the same bedroom, shades drawn. He takes pills, some turquoise like the backyard pool, others white to compensate for the absence of light. He is all we talk about. Why does one child thrive, the other hide? All our holidays and reunions, all our birthdays and breath, are devoted to him. My mother says, Merry Christmas, the doctors think it’s ADHD; happy birthday, it’s borderline personality disorder; pass the white meat, it’s plain old depression.

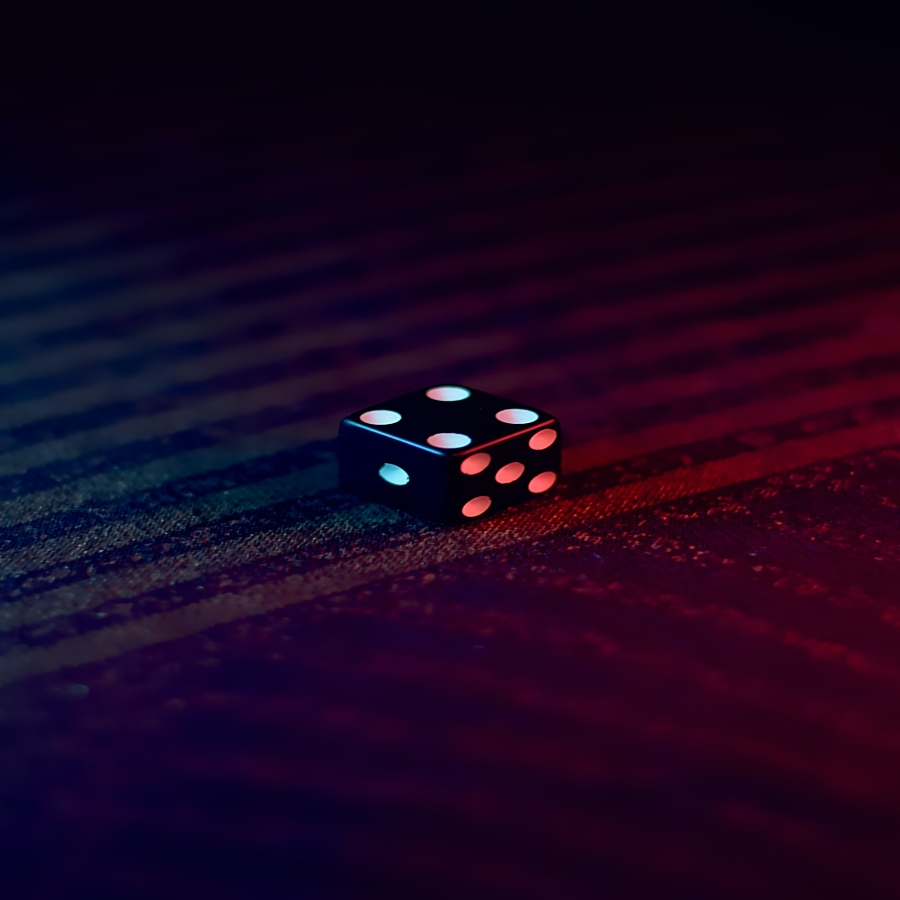

These doctors, they’re picking diagnoses from a hat, rolling the dice and seeing what comes up. They don’t know what I know: that he can’t leave home; that each morning, our parents asleep, he comes downstairs to search for his car, his future, his lost children. They are slivers of pink and blue plastic, negligible as eyelashes. They are buried somewhere in the pile of the carpet. Because I was unkind, because I needed to win. My nieces, my nephews. They are four planets away from the sun.

This story appeared in slightly different form in StoryQuarterly, #33, 1997 pp. 47-48