K Chiucarello: First, I want to say congratulations on your recent Paris Review publication. It is such an astounding essay. I was awestruck with the two lists you made, one in which you needed to make to stay alive and the other of what you wanted to accomplish in the future, these usually tangible things that very suddenly were taken away in the pandemic. Something I admire in this piece, and in any piece that manages to take the pandemic and turn it into a unique yet universal essay, is that while loss and grief are central to the narrative, sharing and writing to stay alive are just as central. I was wondering if you could speak to sharing your experience, particularly your experience as a Black woman, and having it resonate, consumed, and shared by so many folks that may be outside of your own identity. How do you protect yourself and your own story when others can now formulate it to their own?

Megan Giddings: While reading this question, I did have a visceral, would you ask a white writer this question? And not in a let’s start this interview with a fight, but what you described initially is what the white dominant culture in the United States asks people all over the world to do frequently. To see a white protagonist as a person to relate to, to care for, to think about the world.

I don’t think reading is the only solution to the inequities and segregation in the United States. But books, television, movies, music, they’re often the first step for many people toward building an empathetic imagination because the places we live, the places we learn, are still regularly pretty segregated.

It’s impossible for me to protect myself now as a much more public writer. But whenever someone essentially asks me for permission to write outside their race or culture, I ask them these questions now (I’m focused on Black here because that’s usually what people want to do): How well do you know Black people? Why should you get to take up space in this conversation? What are you doing to make space and opportunities for Black writers who are still very much marginalized and will probably make far less money and get far less attention for telling their stories than you might get? The first question is one that I think most non-Black people think they can answer with a list. And that shows that already they’re not ready. It doesn’t matter if you knew a Black person, I’m asking you about intimacy, about trust, about reading and engaging and feeling with us. If you can say well, I dated a Black guy in college, well maybe that Black guy should be writing this and you should be writing about being a white woman who is trying to learn how to be a better person.

KC: Thank you for that answer. If I could clarify my question when I say ‘formulate’. When I write from my own identity, sometimes I feel I want to write a piece and give voice to my very specific identity, a queer, non-binary experience. When folks who are straight or cis- relate to and share or retweet my stories, especially if my identity is written all over that piece, I sometimes feel my experience was up for consumption (as you spoke to in your answer), and that that was not the intended audience even though perhaps those folks learned more about an identity outside of their own by reading it. It makes me feel protective of my voice, yet I simultaneously want others to consider my specific experience. Of course, as writers, we can never control fully who reads our work nor should we want limited exposure. But I suppose I was curious if you struggle seeing your specific experience shared universally.

MG: I don’t really struggle with people reading a piece of writing from I guess what I’ll call a shared empathetic experience. They read it, emotionally connect, and they think about me and themself and our shared emotions. I do struggle when someone reads something by me about me and is like well, I’ve never experienced that, so you’re wrong. Or they do some real C student work and pull a quote out of context to back up their viewpoint of the world while totally missing what I was saying. But until I’m on the final drafts of something, I write to please myself. I write to have fun or to think deeply or to escape. It’s only in heavy revisions where I start thinking about the outside world.

KC: The Offing and The Rumpus are such varied displays of voices and stories, largely because their editorial teams seem to be some of the most diverse around. As editors and readers, the onus should be on publications to create teams that understand how to focus and lift writers whose voices are vastly underrepresented. When you’re reviewing submissions or are in the process of editing others’ work, what are the angles you look out for? Even if the “craft” isn’t fully there, how do you create room and help others make names for themselves so that there is a more nuanced, representative pool of stories out there?

MG: The Offing and The Rumpus have much different systems for reviewing work. At The Offing, the fiction team has no one who is male. We are a team of women, some of us are gender non-conforming people. We have a lot of discussions about who is being centered in a work. We are especially interested lately in features BIPOC who are writing experimentally, who are writing narratives of alternate worlds.

At The Rumpus, one of the things that has been really interesting to me to see is how better and better the readers and some white editors are getting more comfortable saying, I think I’m missing a cultural or political point here. It’s not talking to me. ____, can you take a look at this? I think for a long time, issues of gender, race, and class have been conflated with “craft” issues. I think Matthew Salesses has a book coming out in 2021 about that idea that I’m really excited to read.

In general, if you’re a writer and kicking the door closed behind you, if the only people you’re pushing hard for are your established friends or people you think can boost your work in return, you’re part of the problem. I get that it’s hard to make the time to read for literary magazines. I increasingly am conflicted about giving so much of my time to places that can’t pay me. But I also believe that there are so few Black editors and that the work I can do is still important in helping other writers get opportunities that are still incredibly hard for them. I might be taking a different path if I had money or if I felt like I had more influence, because I am getting very burnt out. Right now, I feel like the most effective place I can be is editing.

KC: I often exhaust myself with trying to weave my own experiences into flash, particularly if it’s a “fictionalized” story around identity. It’s almost like shortening the word length creates an even larger urgency to place so much momentum into a tiny space. How do you balance feeling exhausted and energized when writing through a piece like The Alive Sister, a piece that revolves around generational trauma and identity?

MG: I would say my state of being is being exhausted but somehow persisting. “The Alive Sister” needed to be flash because if it was longer, it would’ve been a rant, not fiction. Keeping it as flash allowed me to still be creative, to think of the ways that I could express my grief, my frustrations, my abilities to even speak to a moment that feels like a wound–Tamir Rice was murdered and his murderer will not be held accountable, his murderer was rehired as a police officer, his police union in Cleveland spent significant time advocating for him to be rehired despite the fact that he shot a 12 year old child and did not allow care to be administered to him–and also because of the constraints of flash, have to think about how can I be at my most clear, my most creative, and still leave room for story.

KC: There’s something about fiction that allows for more curiosity and exploration. I suppose a lot of folks tend to label really fantastical pieces as magical realism these days. Your stories often pit totally realistic emotionally-driven storylines against larger, weirder conceptualized narrative arcs. A Husband Should Be Eaten Not Heard is one of my favorite examples of this. You have Aileen so incredibly dissatisfied in love that she turns to luxurious delicacies for comfort. In the end, I was so entranced and lost in the descriptors that I was questioning if these desserts were even a metaphor at all. The weaving is such a sneaky way of focusing in on objectification versus partnership and individualism. What inspires you to build out a metaphor like that? Is there anything currently that has you obsessed or inspired in terms of drawing emotional links to concrete objects?

MG: I think I’m drawn to fiction, and to writing a mix of metaphor and reality because what I’ve learned from living, from teaching, is that about emotions a lot of people do not like being told what to think. There are some exceptions. But, I like writing for people who like to think sideways, who like to solve puzzles, who take pleasure in thinking and making realizations. I wrote a longer story once that I felt was literally about getting abducted by aliens. It’s about a girl in high school where it makes you socially cool and interesting to have aliens abduct you. A friend of mine taught it in his creative writing class and one student was adamant that it was all a metaphor for losing your virginity in high school. My initial thought was that kid is a sex maniac! But the more I thought about it, the more I considered what it meant for someone to find a completely different avenue into a story and still find something that might have spoken to them. It was moving in its own way to see someone’s point of view was so completely different than my own and they still could get so much out of something I’ve written.

Some of my relationship to objects is because I think there’s so much room to illustrate point of view, tone, and character through the way objects are described. One person’s cool pair of sweatpants is another person’s she’s dressing like she’s on her period vibe. I think descriptions of scenery or items are usually the parts of stories that I often skim because so little emphasis is put on how much they can be used to add not just realism to a story.

KC: I’ve read in past interviews that you threw yourself into flash because someone handed you an Amelia Gray piece. I can hear overlap in your tonalities, the way you’ve mastered this even-keeled yet spiraling, unspooling way of telling your fiction. How did you fine-tune that approach to formatting? Where do you begin sculpting pieces?

MG: Everything I write starts with me asking myself a question. I might hear or read something or consider something, and then I keep thinking about it. And from there, I ask myself well, why are you so curious about this? And the answer doesn’t matter. Usually, the best things I’ve written, I can’t explain why I was so curious until after the story is written. For flash, I edit a lot to take out any over explanations. I want things to be distilled. I don’t want to repeat myself unless it’s 1,000% necessary. I go through and look at the rhythm of lines, I try to find a balance between character and action. I don’t like in my own flash when things stay static. If I wanted to be still and paused, I would write a novel. I think of writing something very short as a kind of trust fall, it’s all lift, momentum, and hopefully, the reader is hovering, anxiously, to catch me.

KC: I’m so excited to see what floats to the top of our submission pile and to read pieces that you were drawn to for the flash fiction contest at Fractured Lit. As a reader, there’s just nothing more exciting than landing on a piece that is a gut-punch, after endlessly culling through submissions. I also find excitement when reading pieces from writers who are just emerging and may not have many credentials to their name. What do you look for when reviewing submissions for contests in terms of writers and content? What are the stories you’re looking for right at this moment from the flash world?

MG: Even before the pandemic, a story that is more of a monologue or a person sitting alone in a room thinking had to be very well-written for me to want to finish it. Now, I feel even more disinterested in stories like that. I would be very interested in a story that in a 1,000 words makes me feel like I’d traveled somewhere. I want to feel seaspray, I want to smell lavender under a warm sun, to be among people and not be like, oh fuck you, don’t you cough near me, you no-mask goon. I know a lot of this interview has been focused on big issues, but a good small story well-told that doesn’t bold or underline its big issues is still deeply valuable to me as a reader.

KC: What would your advice be to flash writers who are just starting out and trying to figure the best outlets to submit to?

MG: I would tell them to check the following books out of the library Know the Mother by Desiree Cooper, Black Jesus and Other Superheroes by Venita Blackburn, Forward: 21st Century Flash Fiction, Gutshot by Amelia Gray, read some of the Wigleaf Top 50 for free online, and mark all the stories they like, and then look up where those stories were published. I think getting a sense that flash fiction isn’t just one or two obvious magazines but is spread out (a lot of magazines that aren’t flash-only venues publish flash, a lot of flash-only venues don’t pay) and there are many things to consider could give someone who is doing this seriously a lot to consider before they start sending out. That’s me taking more of an educator approach. I would also say you could do what I did, a friend told me to read a magazine, I liked it (RIP >kill author), sent them a story, they liked it, and that’s how I got started. I still ended up doing what I described above–any time I read a flash I really liked, I would try to find out where else the author had published and make a list that way.

KC: Any routines you leaned on while creating discipline and structure around your own writing practice?

MG: The most regular routine I have is writing down dreams. I think this is the one that has stuck with me the most because it lets me write strange, nonlinear things without judgment. It’s much easier to get into the regular words or feel less self-conscious if every day you transcribe from a sentence to paragraphs the things rolling around your brain. In the past, I’ve done things where I’ll take three consecutive days (over holidays, time taken off work) and made myself write a first draft of a story each day. I don’t believe that someone has to write every day, but I do think that making regular space in your life for writing and reading will remind yourself that what you’re doing is important to you.

KC: As a queer, I am obligated by law to finish this interview on this specific question. What’s your sign? And do you put stock in it?

MG: I am a Capricorn (sun), Cancer (moon), and Leo (rising). I put more stock into these three elements together because I think they say so much about my professional life, my emotional life, and the way that people respond to me. I didn’t put a lot of stock in astrology when I thought about it as only a Capricorn (the I-love-my-briefcase! of signs), but thinking of it as a layered and fun way to consider myself made me feel much more engaged.

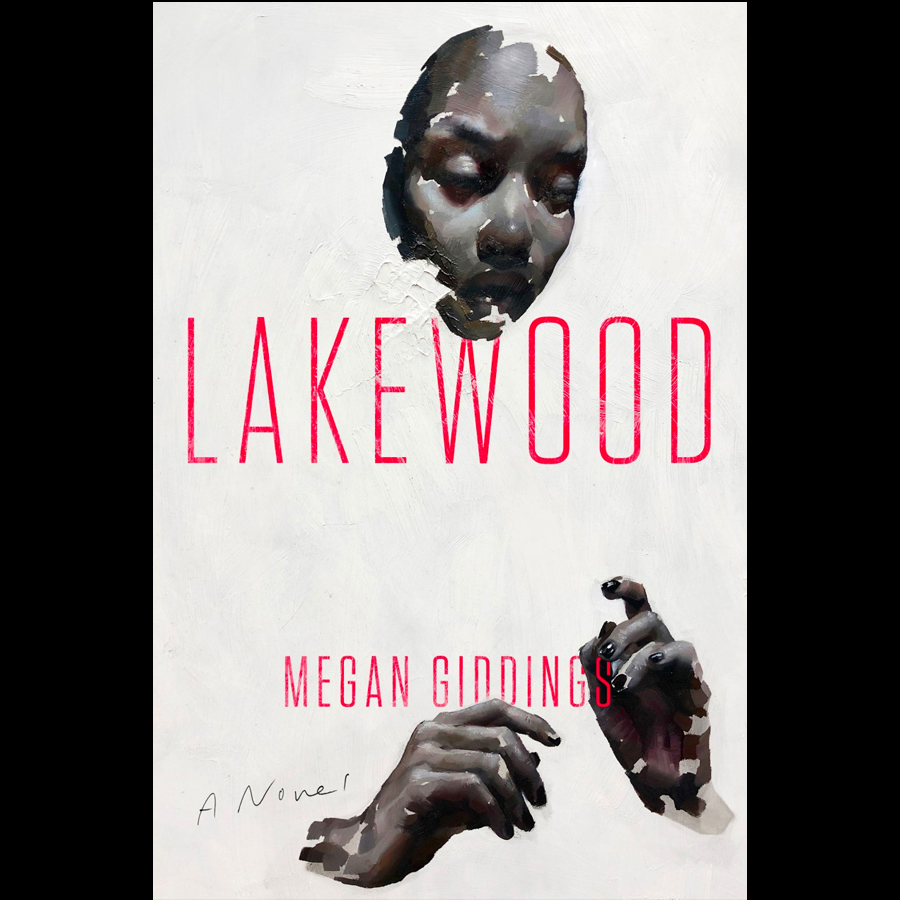

Megan Giddings has degrees from the University of Michigan, Miami University, and Indiana University. She is a fiction editor at The Offing and a features editor at The Rumpus. In 2018, she was a recipient of a Barbara Deming Memorial fund grant for feminist fiction. Her stories are forthcoming or that have been recently published in Black Warrior Review, Arts & Letters, Gulf Coast, and The Iowa Review. Her novel, Lakewood, was published by Amistad in April 2020. She’s represented by Dan Conaway of Writers House. Megan lives in the Midwest.