Albert Abdul-Barr Wang conducted this conversational interview via email during June and July of 2025. Allison Field Bell was kind enough to discuss her multiple practices in writing and photography, just as Finishing Line Press released her latest chapbook, Without Woman or Body, on June 20, 2025.

ALBERT ABDUL-BARR WANG: Hello there, Allie. Nice to meet you, and glad that we are able to talk with each other. I remember when we met first in Professor Laurel Caryn’s alternative photography course at the University of Utah. That was quite the adventure back then. So what drew you as an author and creative writing Ph.D. candidate towards photography? How do you contextualize your photographic and visual art practice within your writing practice?

ALLISON FIELD BELL: Photography was actually my first creative love. In high school, I was very focused on science and math—all set to excel in some STEM field. And then I took a film/darkroom photography class, and well, it was kind of epiphanic for me. Maybe not at the time (I was still committed to being a marine biologist in high school), but looking back, I really fell deep into the well of creating. I was specifically compelled by the role my body played in the creation process. I know it’s terrible, but I loved plucking an image from the developing tray with my bare hands.

I attempted to study photography in college, too, but I was interested in documentary photography and photojournalism. And a professor of mine reluctantly admitted that to do that, I needed to embrace digital image-making. I was not interested in staring at a screen in order to create (ironic, considering this is precisely what writing entails for me these days). So anyway, as an undergraduate, I kept finding myself in writing classes. Not with any clear desire to “be a writer.” But I wanted to create. So, I see photography and writing as very similar impulses for me. And I consider my photographic practice a kind of gateway to creative writing.

AABW: As a fellow photographer and visual artist, I have similar inclinations as you do. In fact, in an overview of your published works through various literary magazines from Flash Frog to The Cincinnati Review, your writing encompasses a gamut of forms ranging from flash fiction to essays to poetry. What drives you towards each particular approach? Recently, flash fiction has been a primary focus. How did you engage with that genre within your writing practice? How would you define your approach and philosophy of flash writing?

AFB: I think genre for me has always consisted of rather porous boundaries. I have certain rules that I adhere to for nonfiction—specifically, a clear allegiance to the truth—but beyond that, I am pretty flexible. I often write through the same event in different genres, trying to find the best way to do it. And also because I believe strongly that we write our obsessions and that the impulse to follow an obsession until it exhausts itself is exactly the right impulse.

With regard to flash, I really started a consistent practice of writing these smaller pieces as a way to balance out my novel-writing. Though, really, it’s unfair to call them small, as they often contain whole huge worlds. Still, though, I feel like, for me, fewer words to complete a draft of something is different work. And maybe that’s just my writing sensibility. But I do think writing a novel is long and arduous and incredibly emotionally demanding, and so I sought out relief from that. Flash feels lighter. Like I can play on the page, and if something fails, well, likely I didn’t spend ten years writing it (which is how long it took me to write my first novel).

I also can’t not mention SmokeLong Quarterly here. I owe so much of my flash knowledge and inspiration to Christopher, Helen, and everyone at SmokeLong and in the workshop community. I write most of my flash these days from specific prompts, and I get so much excellent feedback from SmokeLong Workshops. It’s not just about feedback, though; the SmokeLong community is also incredibly supportive and kind. I feel driven to keep writing flash partially because I so value being part of that community. So often, writing can be isolating, but I think it’s actually really importantly collaborative. I’ve also found other workshops to, at times, be unproductively competitive. This has never been the case in a SmokeLong workshop. I actually call these flash writers my SmokeLong family, and that feels really right and true.

AABW: That’s very true indeed. Balancing the time alone with time spent with others in the literary community can be challenging. Also, what books and artists have you been reading or looking at recently?

AFB: Well, to be honest, I’ve been on a narrative hiatus for a bit. I just finished my PhD qualifying exams, and the experience kind of ruined reading for me for a minute. I’m slowly getting back into a groove, though. I just read through a lot of Mary Gaitskill’s work in preparation for an interview with her. And I’m once again enchanted by her as I was as an undergraduate. Her writing is so candid, so without artifice, and yet there’s so much depth and complexity. She writes the kind of stories that really linger.

AABW: Now I would like to steer our conversation into another direction, which I deem imperative. As the political climate within the United States becomes more oppressive during the post-truth and Trumpian eras through the rollback of female rights, such as the revoked access to abortions, as well as the demonization and detention of immigrants within the public sphere, do you see your writing as a response to our milieu? If so, how do you combine your writing observations of incidents based within your personal life within the greater context of the sociopolitical conditions that are ongoing today?

AFB: Such good questions, and the kinds of things that I have been thinking through for a long time now. I don’t know if I have a great answer. I do feel called to write, but I don’t think there’s much power in that. I think, in fact, any time I feel powerful in creating art, I have to immediately stop and remind myself of the truer experience of art-making, which is really, for me, centered around vulnerability. Vulnerability is also powerful, but not in the way that we imagine. Often, the feeling is like walking around too open to the external world, so willing to take in and absorb what exists beyond the self. To be influenced by what surrounds us. This is what I believe writers can offer. In many ways, we are more like sponges than mirrors.

This inevitably results in a greater context of sociopolitical conditions, but it’s so important not to have an agenda about that. Sometimes I want to write about a lost love, not because I’m interested in interrogating the patriarchal parameters that defined our relationship (I am interested in that, of course), but because my heart hurts. I guess that sounds like writing can equal catharsis, and it can sometimes. But I also often feel like writing is somewhat painful too. A pleasurable and yes, important, kind of pain.

AABW: Like you, I have lived in both Utah and California, where I am located currently. So, as a Californian transplant in the heart of Utah/Salt Lake City, how do you see your works as inspired and/or reflective and/or critical of the Western landscape and its concomitant cultures, such as the cowboy/Wild West tropes or Mormonism? What do you think are the key facets that you like to explore? Have your experiences in California impacted the way you view your current life in Utah?

AFB: I am very much a creature of the western US landscape, yes. I have spent most of my adult life in the Southwest or the Mountain West, and my whole childhood in Northern California. This inevitably influences my writing and my thinking about myself as an artist. My relationship to water is a huge part of that. Water is kind of the great miracle we always fail to fully appreciate.

As far as Western culture goes, I’d say that so much of my way of being in the world has to do with an awareness of landscape. And wild places. Animals and plants. I find myself increasingly aware and curious of shifting plant life, of the saturation of green living things against a backdrop that is often seemingly stark and unforgiving. I love the desert and the ocean equally. Mountains and snowmelt rivers, and the glorious coast of northern California. All of this land and water is forever a part of my body and thus my work as well.

I suppose one Western theme I am overwhelmingly complicit in is car culture. I hate what cars have done to our environment, and simultaneously, I love the freedom of movement a car affords in the West. In high school, I drove myself to the Pacific at least three times a week. I think it is the thing that allowed me to survive high school, actually. The drive out to the beach. The salt air and the wet sand. The sea curling and cresting against my angsty teenage body.

I’m always influenced by the places I live. Whether that’s the Middle East or Greece, California or Salt Lake City. For the most part, I find it easier to write about these places when I’m not actually living in them. I guess this speaks to the question about Salt Lake City: I’m not sure I’ll quite know what I want to say about living in Utah until I’ve moved away. I feel like I carry geographies with me. Place really shapes the way I see the world, and I’m happy to let it.

AABW: That’s so true indeed. Geography often does weigh upon us in such a meaningful way. So do you see your literary oeuvre as being feminist in any sense of the word? If so, how would you define your own take on feminism? How do you incorporate the framework of the female body within your writings? A solid example would be your recent piece “I take off my clothes for him” in the May 1, 2025, issue of Milk Candy Review. How do you look at desire and its ethical ramifications (or not) within the context of the female body?

AFB: I identify as a feminist, yes. As a feminist writer, well, that feels more complicated. I’m positive I don’t want to ever let my feminism guide my impulse to tell a good and true story—I feel that then we get into writing with a political agenda. I do have a political agenda, in my teaching especially, but I try to leave that behind in my creative endeavors. Mostly because, just like an outline, a political agenda tends to overdetermine a work, and I want to trust my intuition to make narrative choices, not my intellect.

Feminism for me is inherently intersectional. As a first-year college student at UC Santa Cruz, I took an Intro to Feminisms class with Bettina Aptheker, and it changed my life. Feminism is about social justice and environmental justice. It’s about equity. And yes, for me, it is deeply grounded in the body. My own experience of feminism has to do with my specific female body and how it moves me through the world.

Desire is slippery. I like thinking about it intellectually, but I don’t think that actually does much to reveal all its complications. Desire is really a wordless, embodied thing, but still, I love to try to articulate my own desire through words. An oxymoronic compulsion, I suppose.

I think the piece “I take off my clothes for him” is a great example of the dynamism of desire. For me, this piece works because of refrain and language. By itself, the story is quite simple and maybe not even that interesting: a young woman sneaks into a hotel hot tub to skinny dip with the twin of a man she dated, and later the two of them sleep together. The refrain does an odd thing where it both accumulates meaning and loses meaning. Much like desire, it slips into a kind of liminal space where it merges the senses (both sight and sound through rhythm), and in a way, therefore, the phrase forces itself into the body.

AABW: Now let’s turn to a close reading of some of your work, which is so compelling in a remarkable way. One of your quotes mentions that “[let] the language of your flash lead you to its content…. Read your flash out loud as you write it, and let it unfold through your body…” How do you see an oral reading of the words you put down relate to the visual aspect of those words on either paper or their digital counterpart? Do you view yourself as a type of modern-day bard similar to ancient epic poets such as Homer or Virgil? In what sense do you see your relationship with the oral tradition of writing as a method of preserving knowledge from one generation to the next, if that is your intention?

AFB: I would say that for me, the reading-aloud component of my writing process has less to do with oral traditions and more to do with needing to absorb what I write through multiple senses, as I mentioned above. I recently made a new dear friend (who is writing an incredible novel right now), and we talked about how we write more with our bodies than our brains. I think this is what I mean here—that the body is a key component of the writing process. Maybe revision is a good activity for the brain. I’m not sure. But I know that writing itself is very much of the body, which is strange because as I write, I often forget I even have a body. I’ll have a leg cramp for half an hour and not notice. It’s contradictory but true.

As for the oral tradition of storytelling, I’m trying very hard to be the kind of writer who is comfortable sharing my work aloud with others. I get terrible stage fright, and I’m often incredibly critical of myself—my words, my facial expressions as I read, etc. I actually have a lot of social anxiety, despite being an extrovert. I have worked really hard to be comfortable in social settings. The point is, I’ve been forcing myself to read more in public settings, to really embrace sharing my work aloud. It’s not an easy process for me.

More importantly, I think my storytelling instincts very much come from an oral tradition. My maternal grandmother—a woman I never met who died in her forties from breast cancer—was a great storyteller. My mother carried on her tradition and passed along her stories to me. I think this is how I became fascinated with narrative. I remember my mother, too, telling ghost stories around a campfire and that thrill of snuggling into my sleeping bag afterward, reliving her words in my head.

I guess this does relate to preserving knowledge. I do sometimes think of what legacy I might leave my niece and nephews as someone who may not have her own children. I feel like maybe what I can leave behind are stories. Other times, when I’m feeling more cynical, I wonder how much any of that even matters. Will books even matter in twenty, forty years? I try to avoid this way of thinking because it doesn’t lead anywhere.

I do think the important part of oral storytelling is community. There is a relationship between the teller and the listener. This is something I very much value and think about as I read or even tell a casual story. I consider how it’s being received. Lately, I have wanted to hear people laugh. It’s so important right now to preserve laughter, to relish in our ability to laugh.

Simultaneously, I know that this part of my brain—the one that thinks about the audience—has to be completely silent as I write. I cannot think for a second about how my work might be received as I create it. That results in paralysis.

AABW: Indeed, I can see the paradoxical nature of being a writer as caught between a wall of despair and inspiration at times. In addition, the act of writing, as I attest, is never executed within a vacuum and is part of a larger framework of the writer’s personal and public life. What hobbies do you have at the moment? Do you see your writing and photography as complementary to your endeavors?

AFB: I love this idea, and it’s something I tell my students constantly: expand your definition of what “writing” includes. Sometimes writing is going for a walk in the woods. Sometimes it’s taking a bath with a cup of tea. Sometimes it’s eating a good meal with a dear friend.

I imagine this is true for photography too, though I’ve been a bit tapped out of that world for some time (those damn PhD exams again). It’s so important to just live and not worry about capturing something on the page or with a camera. The older I get, the more I trust myself to absorb what I need to absorb in any given moment. Otherwise—if you’re constantly thinking about how to shape something—you can’t really be present. And I’m quite interested in being present.

As for hobbies, one recent activity I have embarked on is actually rock climbing. Mostly in a gym, as I am still a baby climber, and I find outside climbing as terrifying as it is exhilarating. My partner is a really spectacular climber, and he’s inspired me to try. I’m 38, and I never imagined I’d be trying some brand-new intense physical activity at this point in my life. But that’s like writing, too, I think: it’s important to be open to the world, to try new things, to fail at them. This is all to say that I am not a very good rock climber. I am not a natural by any stretch of the imagination, but I love the challenge. It feels like writing: the way you have to be in your body, and no matter how much technique you learn, you can’t really be thinking as you do it. You have to let all the technique and brain power exist in the background and trust that it will surface intuitively when needed. This is certainly not translating to my climbing efforts right now, but I do see that happening in my writing.

AABW: Just as tragically, lately, the rate of reading books within the United States has been pretty low. Do you see the rise of popularity of flash fiction and flash essays as a response to the decreased leisure time in the life of the average American/worker? How do you distill the complexity of information and images into an extremely succinct series of sentences and phrases? Do you view the idea of flash writing as a critique of the capitalist notion of time, which is rooted in the increased attachment of the worker to labor that is not involved in reflection or personal reading?

AFB: I think you bring up a good point here, but I’m so resistant to seeing flash as a response to, well, essentially short attention spans. I’m sure there’s some truth there, but I also understand flash to be a form that has existed for centuries across cultures. And oral storytelling in the most informal sense could also be considered flash. Still, your point remains: there seems to be an increased interest in flash narratives across contemporary publishing.

For me, flash is less a reader-inspired form and more a writer’s response to the fractured world we’re faced with. I love the journal Fractured Lit for many reasons (the editor Tommy Dean is an incredible literary citizen who has always been such a generous champion of my work). But the title of the journal is so perfect. I don’t necessarily see flash as these distilled, succinct collections of words, but rather as a kind of fracturing of some wholeness. We can call that wholeness the human experience, but it’s always more specific than that.

For me, for example, I have written many flash—fiction and nonfiction—that speak to my experience of domestic violence, both emotional and physical abuse. Two examples are: “No Promises,” published in Chestnut Review, and “Carve,” originally published in The Bridport Prize Anthology 2023 and then reprinted in Best Small Fictions 2024. Maybe it’s this particular subject matter that dictates the form? Although I do have a longer braided essay that speaks to this experience as well (“The Body, The Onion: A Balagan” published by Shenandoah).

I guess what I’m trying to say is that I don’t know about flash as a critique of capitalism, though I love anything that serves to critique a system that is so inherently unjust. I know that for me and my understanding of selfhood, flash makes sense as one avenue through which I can feel my way through the fracturedness that has resulted from experience. I guess it’s partially cathartic for me, but also—if I zoom out and put on my literary critique cap—it’s important for the reader as well. Domestic violence is one obvious example of a common experience that is also so hyper-specific. This makes it important to share, I think. Relatable to a reader. A story that can maybe help a reader process her own experience.

But again, that’s not really why I write any given form. I feel compelled to write flash, and as much as I may try to analyze it, I also believe in leaving a little mystery, in following the impulse, in my intuition.

AABW: I really relate to your intellectual and emotional connection to the genre of flash fiction, which is pretty hard to master effectively. What do you see as your methodology of writing? Do you see yourself as performing research or taking notes as the basis for your words and speech? How do you translate your own personal incidents into the narratives that you select to develop further into your concepts? Do you see your photography as the basis for exploring ideas for future pieces? Finally, would you like to mention anything else for our readers before we head out?

AFB: To add on to what I’ve already said about my writing process, I’d say that, for me, all writing is deeply personal. Which is not to say that I only write about myself. But it’s not to not say that either. Maybe I’m a total narcissist. Maybe a person kind of has to be to be an artist? I don’t know, and I don’t want to make any broad claims like that. What I want to say is that, even in my most fictional character, there is still some elemental piece to them that is me. A place to locate myself and my understanding of the world. It may be an emotional core or an intellectual one, but it’s certainly there.

I know the term autofiction is controversial and even potentially unnecessary, but I love it because I think it makes me understand narrative as a spectrum. Maybe nonfiction is on one side and fiction is on the other. And while at any given moment in a story you could be closer to one side or the other, every narrative exists on that ever-shifting continuum.

I often advise my students to take breaks from academia because part of me does believe that life experiences are important. I don’t think you need some dramatic trauma to be a good writer, but I do think that moving around the world and seeing different geographies and perspectives is helpful not just to write through diverse experiences but also to understand your own beingness.

***

Albert Abdul-Barr Wang is an indigenous Taiwanese-American, Los Angeles-based experimental writer, conceptual painter, photographer, sculptor, video, and installation artist. He received an MFA in studio art from the ArtCenter College of Design (2025), a BFA in Photography & Digital Imaging at the University of Utah (2023), and a BA in Creative Writing/English Literature at Vanderbilt University (1997).

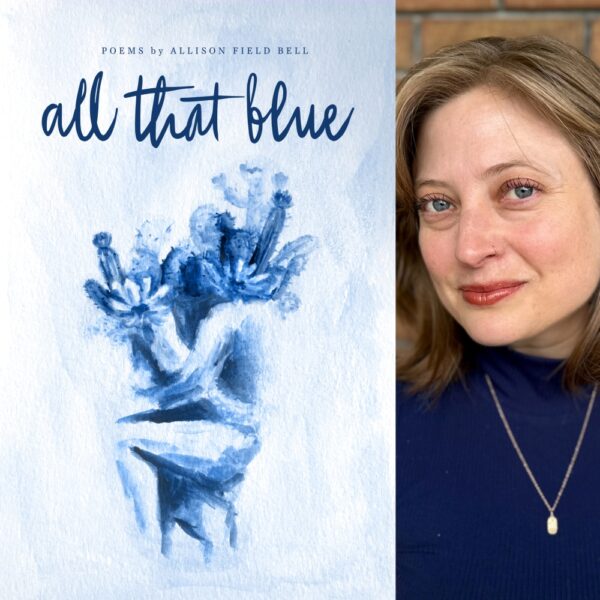

Allison Field Bell is a multi-genre writer from California. She is a PhD candidate in Creative Writing and English Literature at the University of Utah, and she holds an MFA in Creative Writing from New Mexico State University. Her debut poetry collection, All That Blue, is forthcoming in March 2026 from Finishing Line Press, and her flash fiction chapbook, Stitch, is forthcoming in the summer of 2026 from Chestnut Review Books. She is also the author of two other chapbooks now available: Edge of the Sea (nonfiction, Cutbank Books) and Without Woman or Body (poetry, Finishing Line Press). Find her at allisonfieldbell.com