Last stop on the LL line. Subway platform outdoors, a track on each side. A green-lit bulb above each track. The bulb goes green on one track, then on the other, and the people race back and forth from one train to the other, spitting out curses. Up in the control room, the guys are laughing.

A man leans over and blows his nose onto the street. You see it from the back seat of the car. The realtor is driving, showing your parents houses they can afford.

Riding your bicycle around the block, you hit bumps where the sidewalk rises into crests. You ride fast, so that for a glorious second, you fly.

Larry thinks he was supposed to be a girl.

One day in seventh grade, you go to your class and hear that everyone is walking out. It’s a protest, against the two black kids who are bussed to the school.

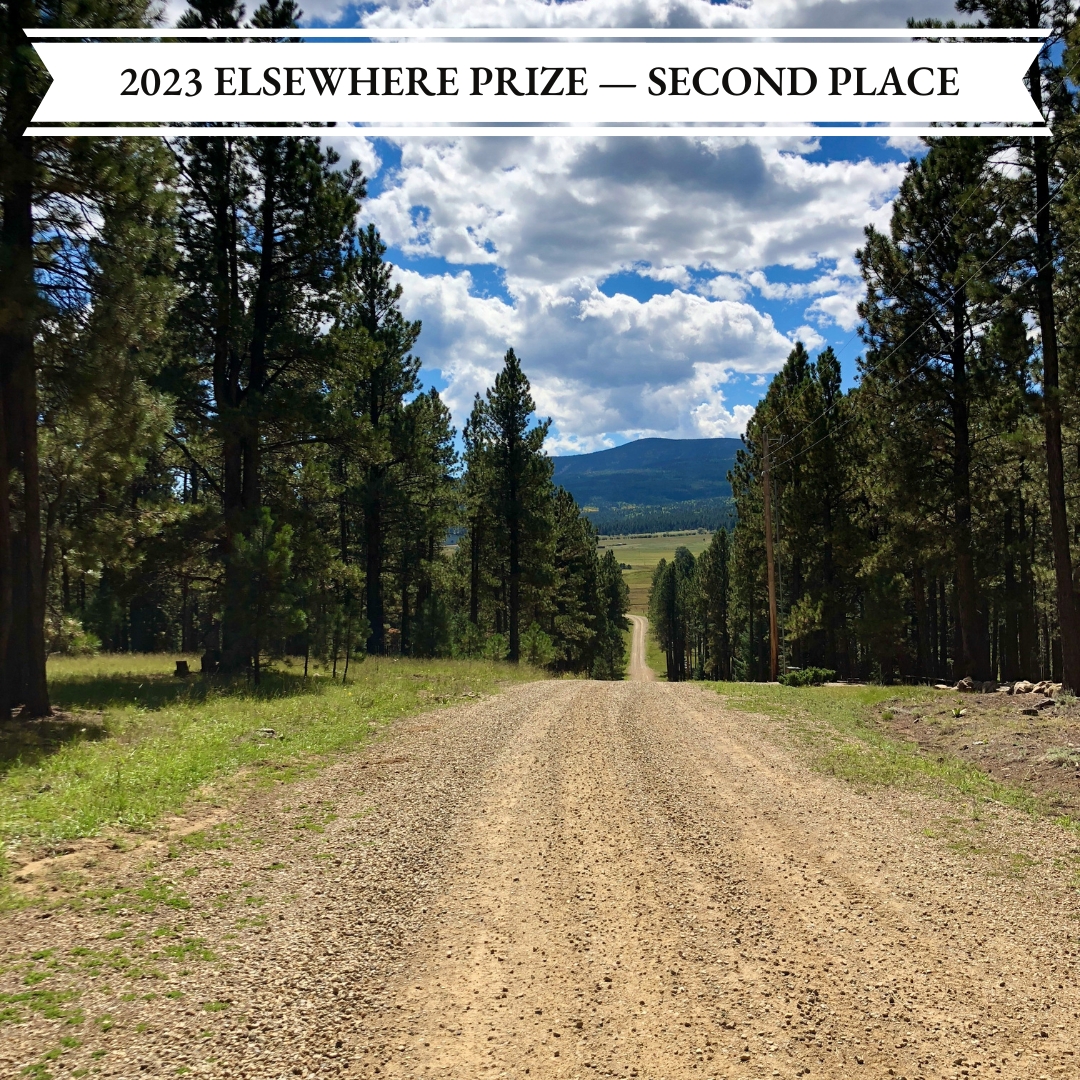

There’s a dirt road you and your sister discover walking home from school. It’s called Smith’s Lane, and a pony lives there. You stop every day to reach through the fence and touch his mane, his coarse coat. You pull up weeds and offer them to the pony, and sometimes, he munches on them with his big yellow teeth. He looks through you, like you’re not there.

Walking to your friend’s house, in shorts and a halter top and new sandals, a boy attaches himself to you, asks your name, your age. You know from his smile, from his slippery voice, that he wants something, and you want it, too, but what is it?

Larry waits until no one is home. He goes into his sister’s room and puts on her mini dress, her high heels, her make-up, her jewelry. He looks in the full-length mirror and sees he is beautiful.

Your parents buy the house with winnings at the race track. You sleep in the one bedroom with your mother. Your father sleeps in the living room. Your sister has the basement. At night, you listen to the dueling snores of your mother and father.

The house sits below street level. You go down two steps, turn left, go down two more. Then, you face a long, narrow walkway. There is a wishing well made of bricks and stone. There are roses blooming. It feels, at first, like a secret, a magical place.

One day, the pony on Smith’s Lane isn’t there. It’s never there again.

Your cat, Suzy, has a kitten. Your sister has joined the Young Socialist Alliance, and the kitten is named Trotsky.

Your sister’s best friend has a younger brother named Larry. He’s in your grade at school. You think he is handsome. His voice is high, like a girl’s, and gentle.

There’s a group of mean girls in your class. Kids call them the rat pack. They have good hair and good clothes, and they pick on girls who aren’t in the rat pack. After school, they surround you and pull your frizzy hair, yank the peace button off your shoulder bag. You’re not good-looking enough to be a hippie, they say.

In the 1970s in Canarsie, there are no black people. There are Italians, who live in small houses with yards, where they grow tomatoes. There are Jews, who live in two-family brick houses with tall steps in front. There are mishmash blocks with no clear character, like where your house sits, below the street.

A very large woman named Minnie lives in the house next door. She stands at the chain link fence between her house and yours, resting her fleshy arms along the top of it and talking to your mother. She comes over and sits in the kitchen, and she and your mother drink Sanka, and your mother puts a bowl of nuts in front of her, and you have to squeeze around her to get by, and you hear her tell your mother in a low voice that you give her the creeps.

On the other side live two old Italian people. A tiny, shriveled woman wearing all black stands in front of the house and beckons you over. She talks to you, and you can’t make out what she is saying, due to her accent and her lack of teeth. Something about when she was a child and knew the answer to the teacher’s question. She tells this story over and over. One day, she isn’t there. The old man in the house wraps his trees in white sheets for the winter, and it looks like mummies are standing in his yard.

Larry uses his sister’s eyelash curler and mascara. A quick swipe of blush on each cheek. He wears tight jeans and a clingy tee shirt. A beaded choker. His body is lean, he moves fluidly down the street, into the fists of the gang of tough kids waiting for him.

On Easter Sunday, the families walk past your house on their way to church. The women and girls wear hats and dangle small handbags from their wrists, and their handbags are the same shiny color—yellow or pink or blue—as their shoes.

The rat pack is outside your house. They call your name. They laugh, meanly. Your sister asks you if you’re going to go outside and talk to them. You shake your head. You wait. Eventually, they leave.

Your brother, who is a grown-up living far away, visits and brings a bar of dark chocolate from Switzerland. It is the best thing you’ve ever eaten.

Larry is released from the hospital. One day, he swallows a bunch of pills and dies.

You go into a candy store after school and ask if they have dark chocolate. The man says no and that he won’t sell dark chocolate. Nobody knows what the hell they put in it, he says. You don’t know what he is talking about. You still don’t know.